By Harvey Kubernik

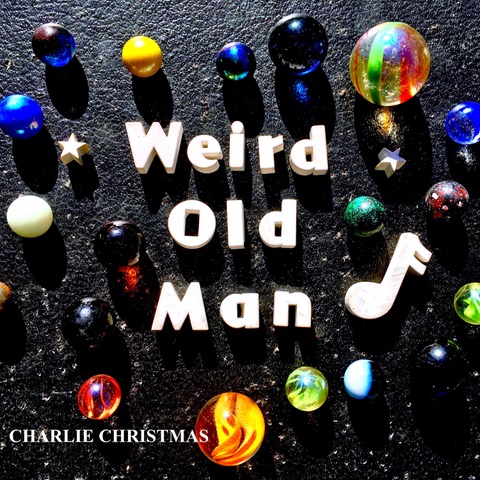

Charlie Christmas aka Chuck Crisafulli is a singer/songwriter, multi-instrumentalist and author of eight books who in December 2018 made  available his debut collection of recordings Weird Old Man.

available his debut collection of recordings Weird Old Man.

The album was recorded in his Glendale, Ca. home studio. Vocals cut in the bathroom and mix down in his garage.

Song titles like “Secret Service Pig,” “Gone So Long” and “Put It Away (Sexual Misconduct Song)” are laced with humor, irony and a unique melodic sense.

The musical influence of Brian Wilson and Frank Zappa on Crisafulli, aka Charlie Christmas is apparent. But make no mistake about the audio results available. This character is an original tunesmith.

File this album under “Pleasantly Unsettling Sounds For Slightly Odd Listeners.”

Harvey Kubernik Talks to Chuck Crisafulli about his new album available on

Q: Where are you from?

A: I grew up in New York. And moved to Chicago for college. At Northwestern University I was in the Writing Program and graduated as an English Major.

Q: I know you as a Los Angeles-based songwriter, multi-instrumentalist, and music-monger. You have spent large portions of your adult life performing and recording with musical outfits “that range from the illustrious to the unlistenable,” as you declare on your website, including Urge Overkill, Moris Tepper, Dogbowl, the Huge Bastards, Shovelhead Bigtop, Filthmobile, Knob & Nozzle, The Blahs, Lisa Parade, The Mobile Homeboys and The Doublewide Kings.

I remember you had earlier played with Urge Overkill and the band staying at your home on Mulholland Drive twenty-five years ago. Chrissie Hynde of The Pretenders came by one afternoon to visit. She was hanging with Nash Kato.

A: I was out of the band by then but my wife and I got to take Nash and Chrissie to the dog park over by the Hollywood reservoir. Not really a wild, rock ‘n’ roll afternoon but a lot of fun. With Urge Overkill I was playing bass. I played drums in high school. And then picked up guitar. As soon as I started trying to get into bands there was always a better drummer or guitarist so bass made sense. My sophomore year at college I met this guy Nathan [Kaatrud]. Nash Kato. I think the second time we hung out we started writing songs together. Nash already had that rock star aura, even as a freshman. Pretty soon we’d recruited a drummer and were scaring the hell out of people around the kegs at frat parties.

We both got really excited about song structure and compositional details and meaningful lyrics that still had a sense of humor. We’d listen to things like Arthur Lee and Love and marvel at the main elements of the songs as well as all the interesting counterpoints going on in the background. Elements and textures Johnny Echols was bringing in. That attention to the little stuff. The Damned was a big influence too. We imagined that we were coming up with equally sophisticated, finely -detailed compositions. Then when we played live it all tended to sound like the Butthole Surfers. Which was still all right by me. The first Urge Overkill releases were on cassettes mixed by Steve Albini. He was also from Northwestern. That early version of Urge was part of a pretty cool Chicago punk scene—we got to play shows with bands like Big Black, Naked Raygun and the Effigies.

Q: When did you relocate?

A: I was in New York for a couple years after college, playing in a lot of different bands. There was a really open, exciting downtown scene happening at that time. It was a real thrill to be up on stage at CBGB’s—let alone sitting in that ratty little green room there or using the very scary bathroom downstairs. I lived in Brooklyn with a guy named Alex Garvin who was the front man of a band called Pianosaurus that played all toy instruments. I had a lot of fun playing with the people I played with, but nothing developed into a steady gig. And the woman who would become my wife decided to move to LA to pursue a film and TV career, so I followed.

My first job out in L.A. was driving a van for a special effects company and I ended up working with makeup master Rick Baker. That was pretty cool. Eventually they let me out of the van to do occasional puppeteering. I actually have some IMDB credits on Gremlins 2, Batman Returns, and the remake of The Blob. I made good money as a gremlin, a penguin, and a blob tentacle.

Q: When did the writing career begin?

A: I got out here in 1989. Working in special effects was great but my real passions were always music and writing, and it started to look like I had a much better chance of covering the rent through writing. I began writing for Music Connection and BAM and in 1992 I had my first Los Angeles Times byline. Nobody was really covering comedy in the entertainment section, so my first pitch to the Times was “What are comics going to do now that Bill Clinton is president.” They had been the voice of the opposition during the Reagan/Bush years, and I wondered if anything would change with Clinton. I found myself talking to comedic heroes like Richard Belzer and George Carlin.

I remember Carlin telling me that nothing would change for him with Clinton—it was just like re-arranging the deck chairs on the Titanic. I did a lot of pieces on the new comedy revival that was taking shape then—the beginning of what would be called Alternative Comedy Standup comedians who were bombing in the mainstream clubs were doing phenomenal, inventive work in new venues—Janeane Garofalo, Bob Odenkirk, David Cross, Patton Oswalt. Like a comedy version of the punk movement.

Q: And you played drums for Moris Tepper of Captain Beefheart fame?

A: Yeah. Most of the music I started playing in Los Angeles was centered around collaborations with my great buddy John Simpson. We put a lot of different bands together. But for a couple years I drummed with Moris, who was in the last lineup of Captain Beefheart’s Magic Band and also played on Tom Waits’ Frank’s Wild Years. Moris is an amazing guitarist and songwriter.

I initially reviewed one of his live shows in BAM. I saw him play in a little club. I did a review he really liked and he got in touch with me. At the time, having an artist actually respond to something I’d written seemed huge. So we started talking. He needed a drummer and I told him I drummed. I showed up at his house in Tarzana. We start playing with the rest of his band. I thought things were going OK but at one point he stopped us all in the middle of a song. He then gave me one of the best summaries of my musicianship I’ve ever heard: He said “Goddam it—You are a great shitty drummer.” Meaning it always sounds like it’s about to fall apart but never does. I’m pretty sure he meant it as a compliment. I took it that way, and was in his band for the next couple of years. We did a bit of touring, including some gigs up in Canada, so I can legitimately say that I’ve toured internationally.

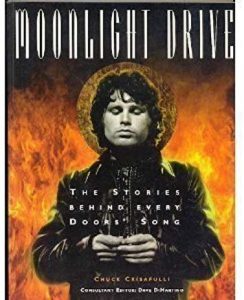

Q: You did a book on The Doors. It was originally titled Moonlight Drive, now published as When the Music’s Over. Dave DiMartino wrote the introduction and was a great guiding presence.

Q: You did a book on The Doors. It was originally titled Moonlight Drive, now published as When the Music’s Over. Dave DiMartino wrote the introduction and was a great guiding presence.

A: I got to the point where I was writing steadily for The Los Angeles Times and for about a dozen magazines: Option, Musician, Rolling Stone, Guitar Player, Bass Player. I just kept pitching and would write wherever I could. I’m pretty sure I was the only Los Angeles Times writer also being published in Hustler and High Times. It was a big deal to me when the opportunity to do a book came along—-to stretch out and take a little more time with something that might live longer than a Sunday newspaper piece. For the Doors book I got to do a deep dive into LA rock ‘n’ roll history and got to talk to a lot of interesting people—Ray Manzarek, Kim Fowley and yourself. Ray was always great. I was so nervous the first time I talked to him, and prepared about four pages of questions. I asked my first question and he talked for half an hour before I had to ask anything else. He liked the way the book turned out, which meant a lot to me.

I mostly pursue book projects now but for the last 20 years I’ve also been writing for the Recording Academy’s GRAMMY-related publications and programs. I’ve had the chance to talk to some interesting people like Moby and Childish Gambino, and have also really enjoyed interviewing legacy artists like Kenny Gamble, Mavis Staples, Johnny Mathis—and—a dream come true—Brian Wilson.

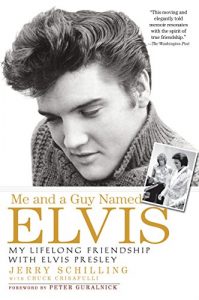

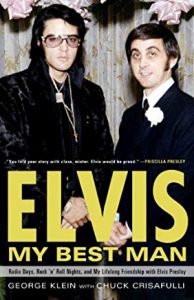

Q: You have done two separate books on Elvis Presley confidantes Jerry Schilling and George Klein.

A: The book with Jerry Schilling was called Me and a Guy Named Elvis. A friend of mine who was doing some talent management was  working with an agent Jerry had been talking to. They suggested that Jerry and I get together. We had a great lunch together at Musso and Frank’s and really hit it off. We decided on the spot to work together. I remember Jerry asked if we should celebrate with a cocktail. I kind of jokingly said, “Well, it’s not 5 o’clock yet..” and he quickly responded “It’s 5 o’clock in Memphis.” Working with him was really a fantastic experience.

working with an agent Jerry had been talking to. They suggested that Jerry and I get together. We had a great lunch together at Musso and Frank’s and really hit it off. We decided on the spot to work together. I remember Jerry asked if we should celebrate with a cocktail. I kind of jokingly said, “Well, it’s not 5 o’clock yet..” and he quickly responded “It’s 5 o’clock in Memphis.” Working with him was really a fantastic experience.

Through Jerry I got to meet George, a well-known deejay in Memphis who for years hosted The Elvis Presley program for Sirius XM. He met Elvis when they were in 8th grade together and was a close friend right up to the end of Elvis’s life. That book is called Elvis: My Best Man.

George was an incredible character and a great story-teller. He just passed away recently, and I’m really going to miss talking to him.

I think it was kind of touching that both of these Elvis insiders had waited so long to discuss Elvis in their own books. They really never wanted to be seen as cashing in and they wanted it to be done right and not put out something sensational. It really was a revelation to me to view Elvis Presley through their eyes—not as an icon or a superstar but as a talented flesh and blood person who was also a really good friend.

I think it was kind of touching that both of these Elvis insiders had waited so long to discuss Elvis in their own books. They really never wanted to be seen as cashing in and they wanted it to be done right and not put out something sensational. It really was a revelation to me to view Elvis Presley through their eyes—not as an icon or a superstar but as a talented flesh and blood person who was also a really good friend.

I also wrote Go to Hell A Heated History of The Underworld with Kyra Thompson.

Q: You also wrote a recent book Running With The Champ with Tim Shanahan, who had a forty-year friendship with Muhammad Ali. Jerry Schilling introduced you to him.

A: Yes. Muhammad was still around when we began that book and he and his daughter Hana and his ex-wife Veronica Porche were very supportive of the project.

Tim is a white guy from Milwaukee that met Ali in Chicago when Ali moved to Chicago to be closer to Elijah Muhammad. Tim was a star college athlete and was still involved in the sports scene and working with a charity that had Chicago athletes like Ernie Banks speak to at risk kids. Tim contacted Muhammad about speaking to the kids, and that was the start of a long, very close friendship. Jerry put me together with Tim. I think Both Elvis and Muhammad Ali fully embraced the public versions of themselves, but they also wanted to share their success with everybody around them. Both took very good care of their friends.

Q: You’ve been making music for forty years as well as being an active music journalist and author. I know you played in a dozen bands over the decades. And you recently decided it was time to make your own album.

A: In my role as a journalist, and an author, I’ve most often been in the position of being a messenger helping to deliver someone else’s message. I guess the album is me taking a shot at delivering my own message. I’m also doing this partially because I looked at the clock. (laughs). If I don’t do this now, then when? So I locked myself in the garage for a while with the idea of creating something presentable. I used the Logic Pro recording system, sort of a pro version of Garage Band. I played everything—guitars, bass, keys, percussion. I had fun stacking a lot of harmonies and using some of the old Brian Wilson tricks of doubling or tripling vocal parts. I did have to get out of the garage to record the drums at a rehearsal studio. Not sure the neighbors would have appreciated my tracking them at home.

I’m happy with the material and recordings. It doesn’t feel like an afterthought or a side project. It really is what I want to say.

On the creative side the digital world and internet makes it so easy to get stuff created and get it out there—but that also means that there is a hell of a lot of homegrown music out there. There’s no guarantee that anything is gonna get noticed. But it still feels good just to get it out. I don’t play poker. I don’t play golf. I don’t do yoga. Music is really my therapy and my exercise program all in one.

And I’m still playing in bands. I’m drumming with a great Santa Barbara-based band called The Doublewide Kings that just put out an album of Neil Young covers called Sleep Never Rusts. And I’m playing drums and occasional washboard with an Americana band called the Mobile Homeboys. A few years back the Homeboys got to do some shows at San Quentin prison, which was a really powerful experience. The first time we played there was a few weeks after Metallica had shot a video there. We got the highest of compliments when one of the lifers told us that he liked the Homeboys better than Metallica.

Q: How has writing about music and doing interviews informed your music?

A: There’s the Harvey Kubernik question I’ve been waiting for. I think there is a connection. As I think you’ve probably experienced, when you get to talk to some of your musical heroes, it’s moving sometimes to realize how much they care about what they do. At the same time, it’s a happy surprise that, as much as some big stars care about what they do, the best don’t take themselves so seriously. So I guess in my own stuff that mix of passion and humor is something I’m always aiming for. And on a basic craft level, in writing and music I’m drawn to things that mix predictability with some well-earned twists—things that seem surprising and inevitable at the same time. So in my melodies and lyrics I always want to find a twist. You think the song is going one way but here’s an unexpected new route and a twist. The challenge there—in writing or music—is to make the twist organic and not just clever for the sake of being clever.

Q: Your lyrics actually tell a story. Is that a primary concern in your songwriting?

A: I guess the lyrics focus on story telling. Some stories are more complete. There’s one song on ‘Weird Old Man’ called “(The Band Can’t Play Your) Wedding Song .” that’s based on a true life adventure of the Doublewide Kings and actually has a narrative to follow. I think most of the other songs just capture a moment of some particular emotion or perspective, and the listener is free to fill in the rest of the story.

Q: You comment on the human condition.

A: That’s not the phrase I’d put on any Charlie Christmas merch, but I am indeed a human. The songs are observations on life. Yes, but I always want humor to be a part of it. I don’t like to take myself too seriously. I don’t want anything to come across as “wacky” or “goofy,” but I also try to steer hard away from being considered an “earnest singer-songwriter.”

Q: Maybe this is a sonic question. I don’t think you sequenced the tracks in an obvious lineup with the lyrics as the connective tissue but the sonic aspect of the recordings really moves the action.

A: Sonically there are some tracks I’m really proud of and I was aware that the first three tracks on the album had to really connect to help ensure the listener would stay with me a while before clicking away to something else. It’s sort of mixed for headphones. It’s old school mono with the wide stereo feel. I will say I played the best guitar solos of my career on ‘Weird Old Man.’ That’s not saying much in terms of guitar solos in general, but it is a personal best.

As far as general production, the influence of late-60s early-70s Brian Wilson is there, especially on the opener, “Place to Stand.” Brian,  Zappa, the Ramones, T-Rex, Pink Floyd, even the radio work of Bob and Ray are all pretty identifiable influences. But of course I wanted to be as original as I could be in the studio. Most of my material grows out of my rudimentary guitar abilities. Some lyrical hook or chorus idea pops into my head, I sit with guitar and try to find the music that fits the words, and then build from there. I like being the social observation guy but there is always a voice in my head, ‘Don’t take the obvious contrarian point.’ Find the twist to the twist. For example, “Porno Valley.” You might expect you’re going to hear something obscene, but It’s more like what you would hear from a happy San Fernando Valley real estate person. ‘Welcome to Porno Valley.” (laughs). “Put It Away” is what I’m sure every woman is eager to hear right now—a white guy’s response to the MeToo movement. “Gone So Long” is a slightly skewed reflection on mortality. “Thank You” is a pretty straightforwardly heartfelt song to my wife Kyra.

Zappa, the Ramones, T-Rex, Pink Floyd, even the radio work of Bob and Ray are all pretty identifiable influences. But of course I wanted to be as original as I could be in the studio. Most of my material grows out of my rudimentary guitar abilities. Some lyrical hook or chorus idea pops into my head, I sit with guitar and try to find the music that fits the words, and then build from there. I like being the social observation guy but there is always a voice in my head, ‘Don’t take the obvious contrarian point.’ Find the twist to the twist. For example, “Porno Valley.” You might expect you’re going to hear something obscene, but It’s more like what you would hear from a happy San Fernando Valley real estate person. ‘Welcome to Porno Valley.” (laughs). “Put It Away” is what I’m sure every woman is eager to hear right now—a white guy’s response to the MeToo movement. “Gone So Long” is a slightly skewed reflection on mortality. “Thank You” is a pretty straightforwardly heartfelt song to my wife Kyra.

Q: How do you think Weird Old Man and the music of Charlie Christmas fits into what’s going on in music today?

A: That was another impetus for getting the record done. The days of rock’n’roll defining the zeitgeist are over—-popular tastes have moved on and rock ‘n’ roll is now more a genre and a fashion rather than a cultural force. But In the last couple of years I’ve gotten really excited about hearing music by Ty Seagall, Starcrawler. Khruangbin. Lake Street Dive. Superorganism. All these folks who are doing really interesting, original music that’s not particularly designed to ‘break big’—but it’s absolutely authentic and really well executed and in some way connects to what I’ve always loved about the odd fringes of rock ‘n’roll. Music that’s unabashedly strange, maybe a little dangerous, but with a sense of fun. That’s a party I’ve always been comfortable at. If you’re looking for music that’s weird, heady, fun, and with extremely limited commercial appeal, Charlie Christmas might be right for you.