A Place in Time to premiere on EPIX on May 31st

Harvey Kubernik the head of editorial at cavehollywood.com in 2019-2020 served as a

consultant on a new 2-part documentary Laurel Canyon: A Place In Time. Alison Ellwood is the director who previously helmed the authorized History of the Eagles.

Laurel Canyon: A Place In Time debuts on cable television Premium network EPIX that will be broadcast on Sunday, May 31st at 10 p.m., and conclude the following Sunday, June 7th at 10 p.m.

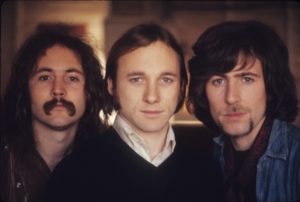

It’s an intimate portrait implementing rare and newly unearthed footage mixed with audio recordings and photos, features all-new interviews with Love co-founder Johnny Echols, Chris Hillman and Roger McGuinn of the Byrds, Little Feat’s Paul Barrere, Sam Clayton and Bill Payne, Alice Cooper, Richie Furay, Michelle Phillips, Micky Dolenz, Graham Nash, Ray Manzarek and Robby Krieger of the Doors, the Turtles’ Mark Volman, Jim Ladd, David Crosby, Bonnie Raitt, Don Henley, Jackson Browne, Bernie Leadon, Eliot Roberts, David Geffen, Russ Kunkel, Owen Elliot-Kugell, daughter of Mamas Cass Elliot as well as photographers Nurit Wilde and Henry Diltz whose work is spotlighted.

Executive produced by Frank Marshall, The Kennedy/Marshall Company; Darryl Frank and Justin Falvey, co-presidents of Steven Spielberg’s Amblin Television; Craig Kallman and Mark Pinkus, Warner Music Group; Alex Gibney, Stacey Offman and Richard Perello, Jigsaw Productions; and Jeff Pollack. The film is produced by Ryan Suffern, The Kennedy/Marshall Company, and Erin Edeiken, Jigsaw Productions.

“As for Laurel Canyon…My father Barney Kessel, a jazz icon and record producer, lived in Laurel Canyon in the late forties on 8051 Willow Glen Road,” offers David Kessel, CEO Cavehollywood.com.

“Barney resided in this now heralded region which gave him easy access to Hollywood and San Fernando Valley to drive to Norman Granz-produced recording sessions with Charlie Parker, Fred Astaire, Art Tatum, Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald as well as live bookings in downtown Los Angeles and the Light House in Hermosa Beach.

“During 1956-1960 he headed A&R for Granz’s Verve label in Beverly Hills while holding the number one guitarist position in the Down Beat, Playboy and Esquire magazine polls from 1947-1960.

“In the fifties and sixties he was a first-call session guitarist on recordings by Elvis Presley, the Coasters, Larry Williams, Julie London, Ricky Nelson, the Monkees, the Byrds, Sonny & Cher, the Beach Boys, John Lennon, Johnny ‘Guitar’ Watson, and Phil Spector-produced Wrecking Crew dates while working with Shelly Manne, Ray Brown, and collaborating with Herb Ellis and Charlie Byrd in the Great Guitars.

“In 1967 Barney Kessel’s Music World was located on Vine St. in Hollywood. Customers included George Harrison, John Lennon, Neil Young, Stephen Stills, Chris Darrow, Frank Zappa, Al Jardine of the Beach Boys and Bobby Womack. In 1969 Barney did an album for Atlantic Records, HAIR IS BEAUTIFUL.

“Over the last two decades cavehollywood.com has proudly exhibited a plethora of Harvey Kubernik articles, essays and interviews with veterans of Laurel Canyon: Micky Dolenz, John Densmore, Robby Krieger, Ray Manzarek, Roger McGuinn, Chris Hillman, Johnny Echols, Mark Volman, Howard Kaylan, Richie Furay, Don Randi, Guy Webster, Michelle Phillips, John Mayall, Danny Hutton, Graham Nash, Henry Diltz, and Nurit Wilde around his 18 published book titles.

“Harvey’s literary music anthology Inside Cave Hollywood: The Harvey Kubernik Music InnerViews and InterViews Collection Vol. 1, was published in December 2017, by Cave Hollywood.

“In 2009 Harvey wrote the acclaimed coffee table book Canyon of Dreams: The Magic and the Music of Laurel Canyon, published in paperback edition in 2002.

“New Mexico-based reviewer Damien Willis in the Los Cruces Sun News touted his title. ‘If you’re interested in learning more about the Laurel Canyon scene, I’d recommend a fantastic book by Harvey Kubernik. It features a foreword by Ray Manzarek of the Doors and an afterword by music producer Lou Adler.’

“After seeing the EPIX preview trailer of Laurel Canyon: A Place In Time I asked Harvey, a graduate of West Hollywood’s Fairfax High School, who took his Driver’s Education class lessons in Laurel Canyon, to provide oral histories from his own 1974-2020 interviews with the Laurel Canyon: A Place In Time screen participants.

“Harvey and I really wanted to give our viewers a real authentic sense of Laurel Canyon’s legendary 1965-1975 musical community. Harvey suggested transcribed voices in a multi-voice narrative. He selected over 30,000 words from the 1.2 million in his Laurel Canyon file that I’m proud to display around Henry Diltz’s photographs.

“In 2013 Harvey, Henry and archivist/librarian Gary Strobl teamed with ABC-TV in 2013 for their Emmy-winning one hour Eye on L.A. Legends of Laurel Canyon program hosted by Tina Malave.

“Special thanks to Henry Diltz and Gary Strobl for supplying pictures which Harvey picked for display.”

Henry Diltz:

“The Beatles changed everything. They took our Everly Brothers harmony and put it together with that skiffle music and came up with a new joyful thing. As folk musicians in early 1964 we heard and saw them on The Ed Sullivan Show. We pulled into a motel, rented a room and watched them on television. We saw them and said, ‘Wow.’ We want to make music like that. Why are we singing about the ox driver? We want to make joyful music, and we need to get an electric bass and trade in our upright bass. So did every other folk group, like the Byrds and then Buffalo Springfield.

“We would go back and forth between New York and Los Angeles. We’d sometimes play the Troubadour for a week or two weeks in a row. And A Hard Day’s Night was billed at an all-night movie theater on Hollywood Boulevard. There were two houses on Hollywood Boulevard that had double features and open to 4:00 am. We went to a screening after a Troubadour show. I had a little reel-to-reel tape recorder, and I sneaked it in under my coat and sat it on my lap and recorded the whole soundtrack to A Hard Day’s Night, ‘cause I wanted to also hear the dialogue with the songs. I went back and saw it a second time.

“It was around then I first met Gene Clark. I was at the Troubadour one night when they had tables near the bar. And there was my friend David Crosby and Jim (later Roger) McGuinn, with another guy. ‘Hey Tad. Meet our new friend Gene Clark. He just moved here from St. Louis and we’re going to start a group and call it the Beefeaters.’ I went, ‘Oh man, that’s great.’ I was Tad at the time, and changed my name, like Jim later did to Roger, from our belief in Subud.

“They loved the Beatles, and McGuinn would get up on stage at the Troubadour hoot nights and do Beatles songs solo on a Rickenbacker. I sent my girlfriend Alexa in Hawaii a letter about the MFQ in Hollywood and the new Beefeaters group.

“In 1965 I was living in Laurel Canyon. I went to Gold Star studio in June 1966 when Buffalo Springfield was doing their debut album. I had recorded there before with the MFQ and Phil Spector. I was in the room in July when Buffalo Springfield cut ‘Nowadays Clancy Can’t Even Sing.’ I met their dog Clancy in the parking lot.

“For their Buffalo Springfield Again back cover, Stephen called me one day and said, ‘Hey. I’d like you to write out this list of names that inspired us in your calligraphy handwriting. People we want to thank.’ I’m in there as Tad Diltz, my old name.

“Then the Monterey International Pop Festival happened in 1967. As a photographer John (Phillips) asked me to do it. I never thought I was doing something historic. My job was to hang out and take photos of everybody doing what they did because I enjoyed doing it. And it got me around observing me and watching. I was used to hanging out with my friends and just documenting all the things that went on around them. And John Phillips knew that, too. Phillips was full of life and a great idea guy, very good natured. In 1966 and ’67 I had photographed Love-Ins in Los Angeles, and people just walking around. Shooting random shots of people who looked good and asking them ‘Can I take your picture?’

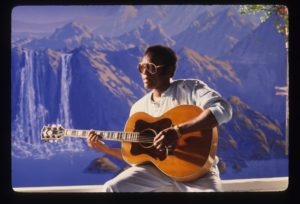

“I saw Ravi at the Monterey International Pop Festival. George Harrison’s devotion to Ravi was heartwarming. We were all discovering India. Ravi’s records were always played in Laurel Canyon with lots of incense curling in the air. And it was sort of psychedelic. And then we were reading Autobiography of a Yogi. And so we were all things India, a place that was looming, a very deep and interesting and informative world.

“Ravi Shankar was our hero. All you ever heard in Laurel Canyon before the festival in the afternoon was his music and incense burning. It was just the soundtrack to our lives. To really see him was great. That was very special. At Monterey everyone was in a trance. Not just the audience, but the others artists, in the crowd, like Michael Bloomfield and Hendrix, were really getting into it, too.

“Micky Dolenz was really into Ravi. At the time of Monterey we were into the Indian philosophy of revering the land and he wore his Indian headdress. I was closest to Micky in the Monkees from shooting the TV show. Micky was a very centered person and not a guy where it went to his head and changed him into something else. He’s a true image. Micky is a true artist. He loved doing what he did. He put his attention into things. People thought The Monkees weren’t a real band, but they proved them wrong. In ’67 I went on a summer tour with the Monkees. Micky was my neighbor in Laurel Canyon and it was great to see him at Monterey.

“Ravi at the time was the soundtrack of Laurel Canyon. And there is a relationship between the banjo and the sitar. They have drone strings, like a bagpipe. There is one note that plays over and over again, which is banjo. It’s the fifth string. It was in mountain modal music. And it was kind of head trippy, you know.

“At the Love-Ins in L.A. there were several hundred hippies meeting in the park having a very pleasant Sunday. People were smoking pot there. In January of 1967 in San Francisco they had the Be-In. And, this was the era of peace and love. And I mean it wasn’t just a word, you really felt that. People were smoking a little grass, which makes you just relax, and just enjoy life, and everyone becomes your brother. Pre-all the bad stuff, just a bunch of gentle hippies gathering to hear the greatest music in the land.

“I just remember being in warm crowds of fellow musicians, not a lot of record company people or promo men, I think they were all huddled together themselves over on the side somewhere.

“At Monterey some of the big boys introduced cocaine, and that was too bad, because that was part of the downfall of that whole wonderful scene. You know, backstage the musicians were eating and the ones schmoozing around together and sitting at tables introducing themselves, ‘Hey man, I’m so and so,’ just getting to know each other.

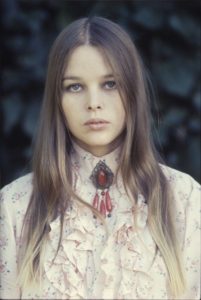

“I loved the Mamas and Papas. Michelle Phillips was very sweet as far as I could see. The camera loved her, a beautiful young girl. The ideal flower child. She had energy.

“Mama Cass was a force of energy. She really was an earth mother and a great spirit at that time. Mama Cass was very intelligent, very funny, and she was very hip, and those three things together were amazing. And she was warm and open and wanted everybody to be friends. She and the group had the first money, big success. Many people came through and stay at her house. You could go up there anytime and not know who would be there, you know. But that’s the way the sixties were. People hung out for the afternoon, and then all go off somewhere else to a club. I loved the Mamas and Papas.

“I knew the Byrds as fellow musicians. I was with the MFQ, did some sessions with Phil Spector, and I played on Bob Lind’s ‘Elusive Butterfly’ that Jack Nitzsche arranged. I didn’t see the Byrds play a lot in 1965 and 1966, except once in ‘66 in downtown L.A. because I was working with the MFQ.

“I knew that Al Kooper has said that during the Byrds’ Monterey set you could see the group breaking up on stage and there was a lot of tension between McGuinn and Crosby. Roger was really steamed when David sat in with the Springfield. It was a different sort of Byrds set from what I’d seen over the two years before. To stand there and watch McGuinn play that Rickenbacker 12-string was mesmerizing. It just put me into a place, and the harmonies, those were the songs we heard everyday driving down Sunset Strip on the radio. So, to me it was magic.

“I do know at Monterey there was tension in that group. Crosby was rubbing McGuinn and Chris Hillman the wrong way somehow. Well, Crosby is a Leo, the royal sign. He’s like a young crown prince of rock ‘n’ roll. He’s a great harmony singer and wrote some fantastic tunes. And Crosby has kind of a naughty boy thing. Holding up the guitar at Monterey with an STP sticker and doing his rap about the Kennedy assassination.

“In 1968 I went to the Miami Pop Festival. Marvin Gaye blew my mind there, in the daytime. The ‘love crowd’ wasn’t in Miami. They were Florida kids and college students, not the ‘Love- In’ crowd of California. I did see the impact of Monterey at Woodstock. But at Monterey there was a lot of hanging out and people and the artists being together.

“At Woodstock the groups flew in on helicopters, and didn’t stay and hangout. And, the groups like Canned Heart, Jefferson Airplane, Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix were younger and kinda fresher at Monterey. There was a lot of love at Monterey, and people performing for their peers. Some of the vibe of the Renaissance Fair of the San Fernando Valley and Agora area, carried into Monterey. The Renaissance Fair was Shakespeare mixed with the L.A. hippie scene, all these booths and lots of foods to eat and wares to buy. They had that at Monterey as well. At Monterey it was a closed venue, a contained little group in an outdoor festival, with bleachers on the side and at Woodstock the massive sea of faces went on forever. It was a huge hoard of people for all the eye to see.

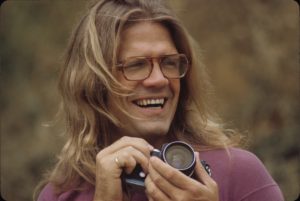

“I knew Stills, Crosby and Nash in their former groups. One day Gary Burden called me. ‘Come on over. We’re gonna take some publicity pictures of Crosby, Stills and Nash.’ We both knew them socially very well. We drove around West Hollywood and took photos in an old antique clothing store. Some photos in Gary’s garage. And then Graham said, ‘a couple of blocks from here I saw this little house that looks kind of nice.’

“We went there and took some publicity pictures, really. Then we got that great shot of them on the couch. By the way, they had not yet named themselves Crosby, Stills and Nash yet. Would it be Stills, Nash and Crosby? And then they figured out Crosby, Stills and Nash right about the time we got the slides back. We had a slide show. ‘Well that looks great, if we call it Crosby, Stills and Nash.’ They are sitting Nash, Stills and Crosby. It would be so simple to go back and put them in order and shoot them the right way.

“However, when we got there a couple of days later, the house was gone. It was a vacant lot. We decided to stick with the album cover, although there was talk about flipping it. If you did that they would be in the right order. I remember my comment, ‘Don’t do that. People’s faces are not symmetrical.’ You can tell if one of the pictures is backwards.

“The debut Crosby, Stills and Nash album along with The Doors’ Morrison Hotel are the pictures I get asked to sign the most. I do them with a brown sharpie and do it on the back.

“As far as shooting musicians live, I prefer being to one side of the stage so the microphone is not in front of the person on stage. And you pick one side or another depending on which way the guitar looks the best. And you sort of get a side front ¾ view from either way. I like to have a nice telephoto lens so I can get them waist up and guitar up. And that fills the frame generally in a vertical way.

“It never occurred to me back in the ‘60s and ‘70s when I was really shooting all these things that it would ever be an archive and that it would be a piece of social history. That’s what it has turned out to be. And that was a total accident. The thought never occurred to me.

“The 12-inch album cover was an art form. It became a real art form. It was the perfect size to hold in your hand while you heard the record and stared at it, read the back and also looked at the pictures. Now, it’s really too small to do that. So nobody sits there and stares at the CD cover.

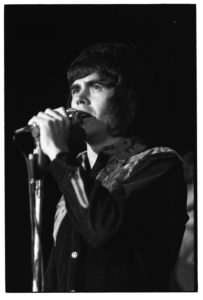

“Jim Morrison, Joni Mitchell and Cass Elliot were telegenic as well as James Taylor and Jackson Browne. The Doors were interesting and weren’t a guitar band. They came from a different place. It was that keyboard thing. They didn’t have a bass. Ray Manzarek played bass on a keyboard with his left hand. It was a little more classical and jazz-oriented. And then you had Jim Morrison singing those words with that baritone voice. It was poetic and more like a beatnik thing. It was different. And Jim wrote all those deep lyrics. I took photos of them at the Hollywood Bowl in 1968 when they did a concert.

“Jim lived in Laurel Canyon. So did Robby Krieger and John Densmore. We were all friends in the area. I knew him as a musician just as I was first really taking photos. I did one day with the Doors in downtown L.A. for Morrison Hotel and got that picture. Then two days later they needed some black and white publicity pictures and we walked around the beach in Venice.

“I photographed things that were around me. And that was part of the society and our generation. I would take a photo. Or I would see my friends rolling a joint or smoking a joint. I would take their picture not smoking a joint. I would take their picture eating a hot dog. Whatever they were doing or playing a guitar. In Laurel Canyon, 1966 and ’67, they had marijuana called Ice Bag, which was a light green.

“With the medical marijuana dispensaries around town, it obviously helps some people who have different kind of pains, or those in chemotherapy, they need it to help them eat. It helps many different conditions. I think it’s great those people can smoke cannabis right now. God’s herb fortifies the immersion of the artistic journey. It stops the jabbering that is going on. Marijuana makes you a better human being. And a better human being cares about where they live, cares about the planet.

“My thought on cannabis and ongoing legalization is that it’s a wonderful tool and gives you another point of view, opens up your mind, a ‘stop and smell the roses thing.’ Since it enhances your senses, it certainly puts you in the world of colors and sounds. It should definitely be legal,” he advocates. “First of all, to me, it is God’s herb. Before I called it God’s herb I used to refer to it as grass. Now I think of it as God’s herb. It’s a flower and I think that maybe it was put here for a reason and we got it all wrong. In these days, the medical reasons are coming out left and right.

“I am very encouraged by the current media coverage in the papers, cover stories in TIME magazine and National Geographic, and especially CNN, with Dr. Sanjay Gupta and his medicinal reporting in his Weed 3: The Marijuana Revolution. I’ve seen some of the fear factor taken out in the media. TV reporters are now investigating and researching the use of herb for medicinal application for seizures after parents had their kids trying all sorts of other drugs. Then they try a little THC and bang! The seizures stop. It’s happened pretty quickly. The outlaw aspect has been removed but people should respect it and use it in a wise sort of way.

“I met Lenny Bruce in 1964, ’65, when we played some gigs together. And he said, ‘it would be legal one day because he knew too many law school students smoking it.’

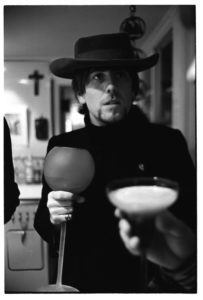

“I remember at The Trip night club in 1965 on Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood. David Crosby, who was then in The Byrds, would walk through The Trip, wearing his Borsalino hat, with a whole box of Bambu rolling papers and handing them left and right to crowd. And you couldn’t find or buy those things then. That was so cool. It was hard to get. There weren’t head shops. This was a wonderful thing. David Crosby was declarative about God’s herb. He was the Prince of pot.

“It’s funny. Micky Dolenz used to say, ‘Whenever they legalize pot it’s not gonna be the same anymore.’ I take his point because it was a thing that we did together. We were brothers in doing this in a communal gathering, which was illegal, as far as society was concerned, but we knew to be such a wonderful thing and it was something we share.

“Sort of like the American Indians passing the peace pipe and feeling a kinship and brotherhood. This was a special secret thing, a sense of community. It’s a wonderful tool if you just learn to use it in a respectful and restrained way.

“Smoking a little bit of grass makes me want to take pictures. It makes me start seeing things. As far as smoking and creativity, making music or framing and taking photos, I think smoking God’s herb kind of turns off the chatter and tapes playing in your head, you know. It makes you just relax and puts you in the moment to enjoy. I never foresaw dispensaries, vapes and pipes and the many different glass and edible items.

“One day I had a photo gallery exhibition with 100 photos of mine on the wall. Somebody said, ‘Did you ever smoke pot with any of these people?’ I looked around the room and I replied, “You know what? Every single one of them except for Mike Nesmith and Donnie Osmond.’ (laughs).

“I smoked pot with Jim Morrison and Jimi Hendrix. I was doing some publicity pictures of the Doors at the beach in Venice as we walked along. Somebody had just sprayed the word POT really big on a wall and we had a giggle, and took some pictures by it.

“I started taking photos and never thought one day I’ll have an archive of history. I think it’s great people can see, purchase and own signed limited editions of musicians. Portrait and concert shots. Wonderful days of peace, love and brotherhood. I’m glad I have this body of work that reflects those things. The fun of framing something up and pushing the button and capturing things that were lovely moments to me.

“My theory about the music of Laurel Canyon was that it was the flowering and the renaissance of the singer/songwriter. I think it had a lot to do with that change that it came from folk music. And then they started putting their own lyrics into it. And, smoking grass had a hell of a lot to do with it. Smoking grass had everything to do with the whole ‘60s thing. Long hair, hippies, peace and love, because that’s the way it makes you feel. And love beads and the music. Smoking a little grass makes you very thoughtful and increases your feeling and focus on things. You start thinking about trying to put thoughts into words and songs.

Roger McGuinn:

“When I recorded the vocal on ‘Mr. Tambourine Man” I was trying to place it between Dylan and John Lennon.

“Chris Hillman and I knocked that off ‘So You Want To Be A Rock ‘n’ Roll Star’ in very late 1966 at his house in Laurel Canyon. It really wasn’t about the Monkees. We were looking at a teen magazine, and noticing the big turnover in the rock business, and kinda chuckling about it, you know, a guy was on the cover that we’d never seen before and we knew he was gonna be gone next issue. A funny little song. People didn’t know how to take it. We just meant it as a satire. We got along well and we wrote well.

“Actually, (David) Crosby and I wrote well too for a while together when we were writing, and so did Gene (Clark) and I. We had some good times writing songs. Chris Hillman played us ‘Have You Seen Her Face’ in the studio and we cut it. We weren’t into making demos back then. Demos came along in the ‘80s. (laughs). Chris Hillman is a very gifted musician. The way he transitioned from mandolin to bass was amazing in a very short. I don’t know if he was completely influenced by (Paul) McCartney but he had this melodic thing, I guess more from being a lead player. He incorporated a lot of leads into his bass playing.

“David is an incredible singer for harmonies and he’s written some wonderful songs as well. I also really appreciated his rhythm guitar work. I thought he had a great command of the rhythm part of it and also finding interesting chords and progressions

“We sang together well. I give the credit to Crosby. He was brilliant at devising these harmony parts that were not strict third, fourth or fifth improvisational combination of the three. That’s what makes the Byrds’ harmonies. Most people think its three-part harmony, and its two-part harmony. Very seldom was there a third part on our harmonies.

“I was driving my Porsche up La Cienega Blvd. and got around to Sunset, and Jim Dickson, our former producer and manager, he had been

fired by the Byrds, shortly before that, he still liked us, or some of us, and he pulled up in his Porsche, and signaled for me to roll my window down. “Hey Jim. You ought to record Dylan’s ‘My Back Pages.’ I said, ‘OK. Thanks.’

“The light changed, I drove back up into Laurel Canyon, and pulled out the Dylan album that had ‘My Back Pages’ and learned it. I then took it to the studio and showed it to the guys. And Crosby hated it because he was mostly upset because he wasn’t getting his own songs on the album, and the reason why he left the band. There was a riff in the band, and he wasn’t getting as many as some of us.

“So anyway, I liked ‘My Back Pages’ and don’t remember any resistance from anybody else in the band, just David. And it was a hit and a good tune. I’m real happy with it. It was Dickson’s suggestion and I hadn’t thought of it as a song for the Byrds’ repertoire. I liked the wisdom of the song and it’s a very insightful song on the thing that happens when you think you’re so knowledgeable and wise when you’re real young. And then when you get a little older you realize what you didn’t know. Dylan’s stuff is brilliant. I coined the term that he was the ‘Shakespeare of Our Time.’ It was like knowing Shakespeare here. Dylan was carrying on Kerouac and Ginsberg. The baton had been passed. I remember Ginsberg said ‘I think we’re in good hands.’

“We did Dylan’s ‘Chimes of Freedom’ at the Monterey international Pop Festival in June 1967. I loved the imagery. You can’t pin it down as a peace song, or whatever, but it’s got overtones of that. It’s brilliant. I just identified with it and could relate to it. I love ‘All I Really Want To Do.’ It’s kind of a simple little love song, you know, but it’s got a really sarcastic whimsical attitude. He doesn’t want to be hassled. He just wants to be friends. We changed the arrangement from the 3/4 time to a 4/4 time. We became his ‘unofficial, official’ band for his stuff. I remember when Sonny & Cher got the hit with ‘All I Really Want To Do,’ Dylan went, ‘On man, you let me down…’ Normally, a writer would be happy to get a hit with his own songs. Who cares who did it? He was on our side.

“Gary Usher got the tune “Goin’ Back” to the Byrds and brought it to us in the studio and played it for us as a demo. I didn’t know of Carole King, even though I had worked in the Brill Building earlier on. And, I had never heard of the Goffin/King songwriting team. But I loved the tune and thought it was really good. Gary explained that these were ‘Tin Pan Alley’ writers who had just kind of taken a sabbatical and come back and revamped their style to be more contemporary, like we were doing. So it really fit well I thought. We learned it and put a kind of dreamy quality into it.

. “I had a lot of history with a lot of people at the 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival. I was also on the Board of Directors and involved in it. It was a real wonderful thing that they did. And Derek Taylor was our publicity guy who worked with the Beatles.

“I really loved Sweetheart Of The Rodeo. We were rehearsing and Gram [Parsons] came in, and there was a keyboard of some kind and I asked Gram if he could play any ‘McCoy Tyner’ because I wanted to continue in the vein of ‘Eight Miles High’ jazz fusion with a (John) Coltrane kind of thing. And he sat down and played a little ‘Floyd Cramer’ style piano and I thought ‘this guy’s got talent. We can work with him.’ That was my original thought.

“Not knowing that he had another agenda, and that Chris and he were like kinda in cahoots and going to sway the whole thing into country music. But I really liked country music having come up in folk I always considered country music, especially the Hank Williams and the traditional country music that Gram was into a part of folk music, so it wasn’t alien to me. And I started harmonizing with Gram, and he and I had a good blend. I was getting into it. It was fun. He and I had a lot of fun for a long time up until he left. Chris and I made a pact that we would never have any more partners and that he and I would be the only partners. And that everyone else would be workman for hire. That was our understanding.

“When Sweetheart of the Rodeo was released some people were heartbroken. There wasn’t a sense of despair, some were disappointed because they didn’t hear the Rickenbacker but those people didn’t show up to the gigs. The people we got were into it and they liked it. There was a fan base that was gonna go along with us no matter what we did. I remember meeting Peter Buck later saying, ‘Well its country, but its good country!’ There were people liking the album right off, and some people were put off by it but they liked it later. After, how long has it been now?

“It takes faith and perseverance. I’m a happy guy. It’s only recently over the last decade that I realized the impact this record has had on people, especially after meeting Jeff Tweedy and Jay Farrar. What is amazing to me is the whole sub culture that formed out of basically Sweetheart of The Rodeo.

“I was a fan of country music and we were dabbling in country rock before Gram came in. And even ‘Mr. Spaceman’ has a country beat to it. I mean, it’s a silly sci-fi song but it’s got a country, Buck Owens approach kind of song. We were dabbling in that and something we did for fun, and the only difference when Gram came along is that we decided to do an entire album of it and do nothing but that. That was the difference. And I think it was because Chris had an ally. That’s what he feels. He found an ally in Gram. And the two of them kind of swung it over to that at the time.

“When we did Sweetheart of the Rodeo there was unity. We used to play poker every day. I mean we were buddies who would sit around, drink beer and play poker. And when we were off in L.A. we’d ride motorcycles together. I mean, we were having a good time. It wasn’t like there was this weird animosity. There was very little of that going on. It was a friendly band, maybe too much fun. We enjoyed it. ‘Lazy Days’ is a cool song Gram wrote. They’re all good songs and we have to give Gram credit for bringing a lot of them to the sessions. Gram brought in a batch of songs. ‘Hickory Wind,’ William Bell’s ‘You Don’t Miss Your Water,’ and The Louvin Brothers’ ‘The Christian Life.’

“We all got along great with the musicians in Nashville and stayed at this Ramada Inn and played poker all day until the sessions at night, and had a ball. We were country boys. We got into it. I mean we had cowboy hats and boots. I loved it, a very enjoyable experience. We were just role- playing, even Gram. He wasn’t that kind of kid. He was a folkie. He was a preppie. Basically Gram got turned on to Elvis (Presley) when he was 10 years old, and that changed his life and he wanted to be a rock star, which he eventually became. And then he got into country, he got into Buck Owens and he got into Waylon and Willie.

“I think what he really wanted to do was get rid of me and get a steel guitar player. Let’s form the Burrito Brothers and call it the Byrds basically. I didn’t want that to happen. I had put too much into the Byrds.

Chris Hillman:

“The music of the Byrds is melody and lyric. One thing I’ve said before, and what our manager Jim Dickson drilled into our heads, the greatest advice we ever got, and he said, ‘Go for substance in the songs and go for depth. You want to make records you can listen to in forty years that you will be proud to listen to.’ He was right.

“Here we were. Rejecting ‘Mr. Tambourine Man.’ Mind you, I was the bass player and not a pivotal member. I was the kid who played the bass and a member of the band. Initially all five of us didn’t like what we heard on the Bob Dylan demo with Ramblin’ Jack Elliot. We were lucky. And Bob had written it like a country song. And Dickson said, ‘Listen to the lyrics.’ And then it finally got through to us and credit to McGuinn, mainly Jim arranged into a danceable beat. The Byrds do Dylan. It was a natural fit after ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’ was successful. Roger (then Jim) almost found his voice through Bob Dylan, in a way, literally voice through Bob Dylan in a sense.

“I’m not a big fan of the Wrecking Crew’s track of ‘Mr. Tambourine Man.’ It’s way too slick for me. Yes, we probably could have cut it. I don’t know if we would have had the success. And I understand completely from a business sense why Columbia and Terry brought in good session guys to cut a good track. Let’s hedge our bets here and let’s get this thing and get it as best we can. That’s fine, but not my favorite Byrds record. Whatever that means.

“Recording at Columbia studio. I remember that Columbia was a union room. The engineers had shirts and ties on. Mandatory breaks every three hours. Record producer Terry (Melcher) was a good guy. I didn’t really get to know him. I was shy. Columbia was comfortable to record in there. Terry was good. I liked him. I will say this, and on the Byrds albums I was not mixed back. Sometimes it worked. And I do have to say all five of us were learning how to play. Once again, coming out of the folk thing and plugging in. And we were all learning. Roger was the most seasoned musician, and we all sort of worked off of Roger. He had impeccable time. Great sense of time. His style and that minimalist thing of playing that was so good. He played the melody.

“And then we start doing some Dylan stuff. ‘Chimes of Freedom.’ Great song. ‘All I Really Want To Do.’ At Monterey we included Dylan’s ‘Chimes of Freedom.’ I didn’t realize how beautiful that lyric was until years later. ‘Chimes of Freedom’ is a killer. It’s just one of Dylan’s beautiful songs. And he was just peaking then.

“‘Bells of Rhymney’ is my all-time favorite Byrds’ song. What song best describes the Byrds? I would say that, because of the vocals on it.

The harmony, because of the way we approached the song and we had turned into a band. We had turned into a band with our own style.

“We went from doing Bob Dylan material and then we take ‘Bells Of Rhymney’ and it’s our own signature rendition of it. It’s not like Pete Seeger’s at all. It’s our own thing. And Michael Clarke, who was a lazy drummer but when he was on he was great. And he’s playing these cymbals. A great experience. I just love that cut.

“The Younger Than Yesterday album. I started really writing songs after Crosby and I were on a Hugh Masekela session that Hugh was doing with this South African gal Letta Umbulu. A wonderful singer. All the musicians were South African with the exception of Big Black. I played bass on a demo session. Such warm loving people. And David was a good rhythm guitarist. A pianist Cecil Bernard was very inspirational. I went home and wrote ‘Time Between Us.’ And ‘Have You Seen Her Face’ influenced by a blind date Crosby had set me up with along with other young ladies.

“The Byrds on Turn! Turn! Turn! album with ‘Satisfied Mind,’ which really was a Porter Wagner hit, and I think we had heard Hamilton Camp do it, but it’s such a great song. And then, I still think ‘Time Between’ was our country rock song of the time. That’s when we started doing that stuff. When we had Clarence White come in and played on Younger Than Yesterday. I’m not taking credit for any of that. Rick Nelson deserves credit in the country rock thing, too. Big credit. Way beyond anybody else. But you know how this business works.

“Gary Usher was an incredibly gifted producer to work with. Especially at the very end, and it was just McGuinn and I trying to finish Notorious Byrds Brothers. And Gary worked with us as another band member. Good ideas. Gary Usher brought us the Goffin and King ‘Goin’ Back.’ I don’t have a problem with that record. That was Gary bringing in a song that fit us like a glove. It was perfect and its Roger and I singing lead. It’s a little too pretty but it’s OK.

“The original concept in 1969 of the Flying Burrito Brothers was as plain as day. Here we are. We wanted to do country stuff. And the first two years with Gram was very good, very productive and on the same page. I think if I was to look back and say, ‘Well, I’f only…’and I don’t go there, but if I did, and it was a question presented to me. He was far more confident. He was a charismatic figure. He was an interesting man at the time. I’m not saying he was a great singer. He wasn’t. He was a good singer on a couple of tracks, probably on the first album.

“I knew Gram and I will always cherish a couple of years when we really worked together. We were sloppy. The Flying Burrito Brothers with Gram. I just had come out of a band that recorded ‘Eight Miles High’ that went from doing Bob Dylan songs to being able to do a song like that, to doing something that musical, and to be on a par with the Who or the Beatles. The point is we became a really tight good band. And I’m in the Burritos, and I’m looking at it not from a sterile place of it should be perfectly tight, but it wasn’t.

“We didn’t put any time into it. And I must say, and I’m not padding myself on the back, when Gram left and Bernie (Leadon) and I took that band and we tightened it up and we made it a good band. And when Bernie left we lasted another six or eight months. It became a musical band then. Did it have the magic that Gram offered? Not really. I still was learning how to sing. And Gram was an interesting guy. He had that thing. And I don’t know what the attraction is that other than he died in such a mysterious way. Yes, he did some good songs. He had a bunch of good songs. Two songs, ‘Hot Burrito #1’ and ‘Hot Burrito #2’ are Chris Etheridge songs. Chris brought those in and Gram helped finish them. ‘She.’ Great song. Etheridge. And with all due respect to Gram, he was a good collaborator.

“After 1967 Monterey, what was a cottage industry and starting to develop into a profitable industry and then started to draw in…The ethics took a bit of a slide, not that they were always there, but what was a little cottage industry that was really run by music people, Jerry Wexler, the Chess Brothers, Ahmet [Ertegun], and Mo Ostin, and the people who loved music. And 1967 Monterey all of a sudden the business started to really expand. The gates opened, the flood gates opened. And FM radio, and Tom Donahue was the FM guy and he brought that to the forefront I think. You are looking at a profitable situation and we had the golden area of the recording industry and that the artists had more artistic freedom. They were signed, and kept around for 2 or 3 albums. It wasn’t platinum out of the box or you are out of the label. It was still this little tiny business that kept growing and growing.

“However, after Monterey and I always say 1968, the next year is when everything changed, politically and socially, every which way in our society. Yes, Monterey did open up the record business. I was learning as I went along. I got quite an education. Everyone started to get a little smarter.

“I got to know Paul Butterfield little bit. I remember doing a music festival with him in 1969 in Palm Springs, with the Burrito Brothers. I remember walking with Paul to the promoter’s tent with Butterfield, and he’s got his brief case with a 38 Colt piece in it, and I said to myself ‘this guy really did work on the south side of Chicago.’ Oh…Here we are in the peace and love bull shit and here he’s got his 38 loaded to go and collect his money!’ This guy is real. A real blues guy!

“After the Monterey International Pop Festival we did the Philadelphia Folk Festival with the Burrito Brothers. I didn’t do Woodstock, and I remember Gram Parsons and I were sharing a house in the San Fernando Valley on De Soto Avenue, and Woodstock was on the news, the situation there. We were laughing, and I said, ‘That’s no Monterey!’ And it wasn’t! Isle of Weight came along, and the Burritos were on that Festival Express in Canada in 1970. But we were only on for a couple of shows after we let Gram go. Bernie and I were rockin’ there.

“What holds up that era were melodies. When you heard a new song on the radio the melody will catch you right away. You might hear a couple of lyrics then when you hear the lyrics if they’re strong and really saying something, yes, we do have songs that are sort of very catchy songs, but didn’t last long, like a fast food meal. It was good when you ate it but wasn’t good later. That was it. The Beach Boys. Melody, melody, melody. Even though ‘Help Me, Rhonda’ lyrics fit the melody. It worked. It swung. That era…

“When I do shows, I have people who come to see me play. Either they’re my age or they are young kids. Twenty to twenty five, twenty six who are enamored by the Beach Boys, Beatles, the Byrds and the Flying Burrito Brothers. I think that’s as big part of it and it was real and so honest. Of course, I’m preaching to the choir and telling you things you already know. But the record companies were run by music people, people who loved music. It was not a corporate monster. And they’d sign you and you’d be on the label for three or four albums, you know.

“I first heard Buffalo Springfield before anyone else when Barry Friedman called me to come over to his house and listen to this band. I go listen to them, got ‘em a job at the Whisky, a year before Monterey. They were good live. They were better live than they were on record, right. And the Byrds were better on record than we were live.

“The sixties were wonderful. I look back at the sixties and it’s amusing to me. I don’t hold any grudges about people. I have no animosity toward anyone I worked with. But I look back and almost have a chuckle. People are obsessing over that period, still to this day. Yes, youthful idealism. You have ti be that way when you’re that age. Yes we want one great world and it’s lovely. The human condition does not allow for that. OK. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t have those wonderful things when you are a young person.

Micky Dolenz:

“I also used to frequent a place called the Omnibus, a coffee house. It was in the early ‘60s, this was probably the closest thing to a cusp between the beatniks and the hippie area, on Cahuenga or Las Palmas. I remember clearly it was my first foray into post teenage life, the adult world. I’m going to a junior college in the San Fernando Valley, age 18 or 19, well after Circus Boy. No drinking, and only coffee. This was bikers, and beatniks. No paisley, no bell bottoms, people in black. And still snapping their fingers and reading poetry. I had no idea what the music was about. I was doing Monday night jams at the Red Velvet.

“A little while afterwards, at the time, a lot of the San Francisco groups, 1966, ’67, ’68 all came down to Hollywood and recorded in the same studios The Monkees used, with some of the same engineers. Sometimes they were on the same record labels as us. Also, before I even did the TV pilot for The Monkees in 1965, and the series started to air in 1966, I was at RCA studios every night watching the Wrecking Crew and the studio musicians, play with the singers and songwriters, on Mamas and Papas sessions, the Association songs, the Beach Boys songs. And these same musicians were playing on our songs. I was a singer, I sang. I can’t express how important it was then, and now, to have songwriters. Before The Monkees I had recorded a couple of singles with the Wrecking Crew as a solo artist a year before I went on The Monkees audition

“I remember people talking about the Monterey International Pop Festival happening, but it was almost a spur of the moment thing. We were looking for a great opening act at the time as we had a tour planned. I had seen Jimi Hendrix earlier as a backup guitarist for John Hammond, Jr. in New York. He was a sideman in 1966. Someone told me I had to go to this club to see this guitarist who played with his teeth. I didn’t know his name. John Hammond was pretty incredible.

“Then, at Monterey, I’m sitting and Jimi, Noel (Redding) and Mitch (Mitchell) come on stage, Jimi had gone to England, and Chas Chander out a band together for him. The Jimi Hendrix Experience. By the way, does that mean they were manufactured? Half of Jimi Hendrix’s set at Monterey were cover versions, too.

“Jimi walks out on stage, and I recognize him, because he’s playing guitar with his teeth. ‘Hey! That’s the guy who plays guitar with his teeth.’

“I suggested him for our tour because he was very theatrical. And, the Monkees were theater. You know, let’s not forget that The Monkees were a TV show about a band, an imaginary band that lived in this beach house, and had these imaginary adventures.

“It was theater. It was probably the closest thing to musical theater in television. It was about this band that wanted to be famous, wanted to be the Beatles, and it represented in that sense all those garage bands around the country and the world. On The Monkees show the group was never famous, it was all about the struggle for success that made it so endearing I think to the public, anyway. I saw Jimi at Monterey, told our producers, who got in touch with Chas Chandler and then Jimi’s booking agent. Everyone thought it was a great idea.

“I was studying drums at that time and working. Ravi Shankar was the most moving, spiritual experience and it allowed you to get into the pulse and the rhythm and into the deepest meditation. It was two hours of uninterrupted meditation in the afternoon. It was just being in the presence of those musicians ((Ustad Alla Rakha and Kamala Chakravarty) and experiencing a form of music. The Beatles had sort of introduced it to us, but we had never heard Ravi Shankar do a concert. But this was something new to the entire audience. It was as close to a kind of ‘born again’ experience that anybody could have had in that audience.

“At Monterey during that time, it was all one sort of zeitgeist and the community then was quite small and local, it was only really California and New York that had any real to speak of hippie community, because it was the counter culture, and there was only a couple places in the country you could get away with it without being arrested.

“In fact, one of the most important things, I think The Monkees show contributed to the culture was the idea that you could have longhair and wear bell bottoms and you weren’t committing crimes against nature. At the time the only time you saw people with longhair on television they were being arrested, or treated a second class citizens. The people at Monterey, before and after, at my house were all the same people. Jim Morrison was up at the house all the time. I did some basement recordings with John Lennon. I had the first Moog synthesizer in town that I got from Paul Beaver.

“The culture difference between San Francisco and L.A. still exists to some degree. At the time of Monterey I think I made a donation to The Oracle alternative newspaper in San Francisco. I do remember making a huge contribution, a lot of money at the time, to some Indians in Seattle, or in Alaska, who were put in jail because of a fishing rights dispute. They sent me a beautiful painting after that. I gave them thousands and thousands to bail them out. I wasn’t deeply invested into that counter culture as others might have been. At the time, there were some people who got what The Monkees were all about, like Frank Zappa, my friend Harry Nilsson, and John Lennon.

“Before the hippies there were the beatniks, really. And the commercial pop environment came from that. I’ve often thought The Monkees were hit pop music. Dr. Timothy Leary said in that book, Politics of Ecstasy, ‘The Monkees brought long hair into the living room.’ And I think that may be the legacy. It made it OK to be a hippie, have long hair, and wear bellbottoms. It did not mean you were a criminal, a dope smoking fiend commie pervert. That’s what happened. A kid says, ‘Hey mom, The Monkees have long hair and wear paisley bell bottoms.’

“I remember Ringo once, years later, telling me how the music business has changed so much. ‘You know, all you had to do in the old days was show up with your drums and you were in the band.’ And, that’s true. And there were others who honestly didn’t get it. Rolling Stain magazine to this day still doesn’t get it.”

Mark Volman:

“As far as the vocals and particularly the background vocals on the recordings of the Turtles, the basic overall philosophy of the vocal sound of the Turtles—and this goes back to the four of us: Chuck Portz, Jim Pons, Howard [Kaylan] and myself, and then narrowed down to the three of us, Jim, Howard and I—was that it was necessary to have complementary voices. One of the things that we learned going as far back as Westchester High School was that the second tenor parts, which basically brought the melody, were important for the sound quality of the group. That was left to Howard and I. A lot of times when we would do a record, before Jim Pons became such an integral part of the singing, the backgrounds were done by me, Howard and Al Nichol. Jim Pons brought a lot to the table.

“Howard knew my strengths were in the quality of my voice. My voice got much more familiar to the Flo & Eddie fans, going back to the early Flo & Eddie records. I think there was always something about how we put together first and second tenor, a baritone and bass. I think there was a lot of thought in those background parts, a natural thing. As we became more and more in charge of our records and in arrangements the stuff that we brought became more and more obvious. We were pretty much the shit in terms of production of the sound.

“But, you know, Howard understood that we had the songs and a friendly voice when we made records in the sixties. We had records and a

familiar lead singer from song to song on the radio. That was very valuable. A familiar sound. Howard Kaylan of the Turtles or Micky Dolenz of the Monkees. We understood how important Howard was as a lead singer.

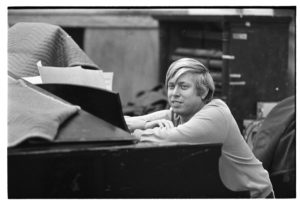

‘“Elenore’ was written by Howard in a hotel room in Chicago as they [White Whale Records] wanted another ‘Happy Together.’ We sat down and shaped that song into the record that would eventually come out. Check out the second chorus. Chip Douglas produced it.

“Chip Douglas was now our producer. ‘The Story of Rock and Roll’ might be one of the greatest productions we have ever done and a powerful arrangement. Unbelievable. That whole high voice thing that we would eventually use on T-Rex records like ‘Bang a Gong (Get It On)’ and even with Zappa and Flo & Eddie.

“‘The Story of Rock & Roll’ was the best recording we ever made. Put it on. We were creating Flo & Eddie with that recording, the songwriting and production. It also showcased for the first time the way sharing our vocals. Howard always had that control and that was the way it worked. You can argue that Howard is one of the best singers of that era. Or any era. Still. A great singer.

Howard Kaylan:

“The only agenda I had as a singer, in the early days, to be as much “Colin Blunstone” oriented as a possibly could. That was my mission. It was to emulate that guy with his soft and loud minor major series of hits with the Zombies.

“In the Turtles, I knew ‘Happy Together’ was going to be a big hit. We honed and developed it over months on the road. Wonderful fate. It was a luxury and it’s appreciated. I’ve never had the luxury to take something on the road for eight months and work it, re-work it and just fine tune it. And certainly when we came back from an early tour was the demo of ‘She’d Rather Be With Me.’ I was really disappointed. There were no other choices in a stack of acetates with that one on the top. The only record we ever received was the new [Gary] Bonner and [Alan] Gordon, ‘She’d Rather Be With Me’ song, and we were now the new Koppleman-Rubin (music publishers). And you better be careful what you wish for. We wanted to be the new Lovin’ Spoonful and have everything written for us and just sort of presented to us on a silver platter, so we could be those good time guys from the west coast, like the Spoons had been for the east coast.

“I did see the Buffalo Springfield at the Whisky a Go Go. The band rehearsed in the house that Mark and I shared in Laurel Canyon on Lookout Mountain. Richie and Stephen slept on our floor. I moved out after a failed drug bust–didn’t know if the house was being watched. Paranoid. Richie moved into my room and the group practiced and wrote there. We all knew well before they played show number 1 that they would be stars. The Atco deal guaranteed it. In the canyon, we were used to our friends becoming stars.

“I was at the Freak Out! recording sessions with Frank Zappa. I saw the determination but I didn’t know the product. At the time it’s not

like I was aware until after the release of the record what a genius this guy was. I still just thought he was a freak. I was living in Laurel Canyon at the time. I might have gotten the album at Wallichs Music City. I get it and we all love the album.

“The next time I get to see Frank was at the Garrick Theater in New York. Maybe late ’66. Or early ’67. Releasing a new record and leaving L.A. was a real big deal to us.

“After leaving The Caravan of Stars, we wound up in 1966 when ‘You Baby’ was about to come out going to play The Phone Booth. The Young Rascals had a hit record, ‘Ain’t Gonna Eat Out My Heart Anymore,’ and they were the house band there.

“Frank Zappa then has a residency at The Garrick Theater and it doesn’t start until late at night. Plus, The Turtles would finish at 10:30 or 11:00 PM every night at The Phone Booth and then we’d go to the Village and we see Zappa. We end up friendly enough with Frank and go every night. And it’s a mind-boggling experience to us. Not just going to the show but going to Frank’s apartment afterwards.

“Back in that era in 1966 and ’67, before ‘Happy Togther’ hit, and we were still L.A. street people working in the same clubs and stuff, there was enough of a camaraderie there. Not only though our knowing him, but also through Herb Cohen and going to the Zappa Log Cabin.

“I loved Frank and the records. He was singing about growing up. I was trying to sing about growing up, too. It wasn’t that far apart. When people say ‘I don’t understand how you guys ever became guys in the Mothers. How did you ever get to know Zappa in the first place?’ And I say to them, ‘man, we were all trying to get the same gigs on Sunset Boulevard.’ And largely that’s true.

“Nobody made distinctions in that canyon of dreams back then as to what type of music you were doing. If you were Lester Chambers and you were living in that canyon Joni Mitchell didn’t question what kind of music you were doing. Nobody did. Everybody was in there for themselves. To make their music shine for a minute while the bright stars were already living there. We didn’t want to change things. We wanted so badly to be a part of it that finding our place was so important. I’m not sure as Turtles we ever found our place but as Mothers we sort of busted out of our comfort zone a little bit. I think the Turtles were comfortable for us.

“Well for me, it wasn’t so much we did on stage it was his demeanor off stage that made him paternal to me. On stage he was a band leader and we were guys for hire. The fact that we got away with improve only meant we were smart enough to know when to get out of a bit in time for the music to come in. That’s what Frank respected. You could go off book as long as you got right back. No beats were lost and something was added. If you added something to the routine it was always appreciated and repeated if you could on a nightly basis or made to be part of the folk lore in some way. If it was not appreciated, Frank would let you know right on stage in no uncertain terms that this was not the time nor the place for that kind of thing. And later you would discuss it with him. It wouldn’t be a slap on the hand parent kind of talk. It would be very familial, more brotherly than paternal, but something that I never had before, which was an older figure that I respected respecting me back. The only other older figures in my life had been agents and managers who pretty much lied to me.

Danny Hutton:

“I was aware of Laurel Canyon, being a native of L.A., and went to Notre Dame High School. The photographer Earl Leaf used to come into a restaurant in East Hollywood I washed dishes in. I was a Hollywood kid by the age of 12. I remember Fred Astaire walking in to Wallach’s Music City and I was listening to demonstration albums in their booths. Dot Records was next door. I went to Pandora’s Box and saw Preston Epps.

“The first time I met Van Dyke Parks was when I was an A&R guy for Hanna-Barbera Music. Maybe 1963. I was at the Troubadour one night and went to a party and Van Dyke looked like a 13-year old boy and was lecturing to everybody. Van Dyke was on The Les Crane (TV) Show in 1965. Van Dyke was a thinker. Van Dyke lived on Happy Lane and the house right across from him is the oldest home in the area, an adobe house that used to be a bordello and gambling house. In the 1940s Laurel Canyon had a lot of hunting lodges.”

“In 1964 I was living in Laurel Canyon. My neighbor was Jack Nicholson, who was a writer. Not an actor then. I remember him taking me and June Fairchild out to Peter Fonda’s house in the Malibu Colony. Jack would come over to my pad after he had an acting lesson. The first time I saw Micky Dolenz was at the Red Velvet after Circus Boy ended and the Knickerbockers were the house band. I auditioned for The Monkees. I knew Bob Rafelson from Jack Nicholson. So I went down there but never made it into the office.

“Laurel Canyon is still innocent. What I learned from Brian Wilson was how good a hit has to sound. “I had my record ‘Funny How Love Can Be,’ which followed ‘Roses and Rainbows.’ I cut it on Sunset with the Wrecking Crew. Earl Palmer on drums. I did the American Bandstand TV show with The Lovin’ Spoonful. I met them and they invited me to their sessions and some of them were done at RCA. They also worked a bit at Gold Star. Dave Hassinger, the engineer at RCA, then takes me into a room. ‘I just cut this a while ago. Check it out.’ And plays me the master tape of the Rolling Stones’ ‘Satisfaction.’ Between that, and being with Brian Wilson when he cut ‘God Only Knows,’ I am listening to the clarity and how present the sounds were.

“All the New York people then started to invade. And the New York people like Tim Hardin were hostile. The aggressive New Yorkers starting to come into the canyon.

“Plus, what destroys so many groups is that their first album comes out and all of a sudden the songwriter of the group pulls up in a Ferrari. ‘Oh I got my royalty check!’ After the band hits then all the people that aren’t needed made jobs for themselves. ‘I’ll be the assistant.’ The entourages start and then the dealers move in. Then it all gets magnified.

“There was a real innocence in Laurel Canyon 1964, ’65. The guy from Dot Records in Hollywood, Randy Wood, wore a suit, like the old A&R guys from the 1940s with the big bands. You dressed a certain way and had three hour-sessions. That was the early transition. Then it started getting serious

“I came to Laurel Canyon in 1964 and I’m still here. Musicians, record label people, producers come here because it’s full of life and change.

“Here it started in the ‘20s with the hunting lodges and then they started building and building and people renting out guest houses to some actor or actress or assistant film editor lives, so everyone hangs and have kids that go to the country store, so you get a community. So you have people that rent and are here for a couple of years.

When I perform with Three Dog Night I’m doing interviews to promote shows around the US And I’m always asked, ‘So, where are you right now?’ And I reply, ‘I’m in Los Angeles in the hills in Laurel Canyon.’ ‘Oh man!’ And I’m usually always able to say, ‘it’s about 70 degrees in January.’ Everybody who talks to me has this thing about Laurel Canyon.

“It is a mythical place to a lot of people. There’s no sidewalks in Laurel Canyon. There are few. When you come up Laurel Canyon in a way you’re not invited. We don’t necessarily want you walking in the neighborhood. (laughs). But we want to visit between each other.

“I first met Reg Dwight (Elton John) in 1969 in England when I was looking for songs for Three Dog Night. So I phoned Dick James Music and Reg Dwight came up to my room and had some demos, which I still have. Reg or Elton, I really liked him. He was so sweet and sincere.

“I invited him to a small club where we are doing a show. The bouncer came up and said ‘Did you invite somebody because I don’t have him on the list.’ He’d come with Bernie Taupin. They were downstairs in the bar and I went down and he was humming something. I said, ‘You’re a great singer.’ And Elton said, ‘Nah. I’m a songwriter, not a singer.’ Maybe he was working me.

“Later on I couldn’t get him on the list for our show at the Marquee Club so we brought him in as our roadie. Reg knew my resume. We were a hot, hot band.

“I heard ‘Lady Samantha’ and brought it to the group. Our producer, Gabriel Mekler, had all three of us sing it and had Chuck [Negron] do the lead vocal. I liked the song. We also did ‘Your Song.’ And then I got a 3-page handwritten letter from Elton thanking me for helping him and Bernie out.

“Elton then phoned from London and said ‘I’m coming to town. He arrived and the first place I took him to eat was Billy James’ Black Rabbit Inn. Then I brought him up to the house. I phoned Van Dyke Parks to come up. And Elton played the piano at my home on Lookout Mountain.

Michelle Phillips:

“The Guy Webster photos of the Mamas and the Papas work in black and white and in color. First of all, we were a very unusual looking group. And it didn’t have to be. Remember the name of the first album: If You Can Believe Your Eyes and Ears. If you believe your eyes you’re gonna look at that picture. And it doesn’t matter if it’s in color. It’s fine in black and white. Because everyone is looking at this very overweight beautiful woman who sang like a bird, and then there was this tall thin blonde with long hair, and this beautiful Denny and this tall guy with a mink hat on. It was something that you just didn’t look away from. You were gonna look at that picture and try to dissect who these people were. We were always very animated, too. So it wasn’t a static pose. The pictures of the group all the way show that we were going through so much. We were always kind of living our drama and seen in many of those photographs.

“Why does our music still resonate and have influence? I’ll tell you what I think. I think that we put a lot of energy into making the material great. John Phillips was such a perfectionist. And so was Lou Adler. That was a big romance. John and Lou were perfectly suited for each other. They bounced off each other. They really appreciated each other’s gifts. John and I had never heard ourselves sing with anything more than one guitar when we went to audition for Lou Adler. So when Lou put together Hal Blaine, Joe Osborn, Larry Knechtel, and engineer Bones Howe, when we heard ourselves with a band it was amazing! It just inspired us more and more. And you know, I think we were very lucky that we picked a lot of good material.

“When John gave you a part you had to learn these incredibly difficult parts. He would say things like, ‘You’ll thank me for this someday.’

And he would keep us in the studio doing take after take until it was perfect. And we would already be complaining an hour before we finished. ‘But that’s the perfect take, John! It’s not going to get any better than that.’ ‘Yes it is.’ And there was just so much material.

“As far as the Mamas and the Papas always connecting. Years ago I came home one day and turned on the television and a special from Vietnam was being broadcast. The camera panned across this audience of soldiers and marines who were fighting in Vietnam. And there is such a look on their faces, this is like 1966, ’67, just right in the middle of this horrendous war, and you can see it just etched on their faces. And the camera pans across them and there is this huge banner that says California Dreamin’. And, that just shook me to my core. It became a destination anthem. I’m the co-writer of that song. And there are still millions of people that hear the music of Los Angeles and it represents their youth that was so tumultuous and so frightening and to so many of their friends and relatives.

“And in a way Mamas and Papas music is comforting to them. You know what I mean? They can go back into their childhood and say, ‘That was the music of my era.’ And, ‘California Dreamin’’ has surpassed any kind of era. And I think ‘Dream a Little Dream of Me’ has done the same thing.

“I think the Mamas and the Papas were kind of like a bubble. It was wonderful when that bubble was floating. And then the bubble popped. And that was the Mamas and the Papas. When you think about it we were only together for two and a half years.

“I think Monterey Pop is a really wonderful film. I saw it two years ago on the big screen in Hollywood for the first time since it came out. You get to see what the festival was really like, and how beautiful everyone felt in 1967 on June 16th, 17th and 18th were all bright sunny days. You see other festivals and they are rolling in the mud. Monterey Pop is so representative of the time. People actually did paint flowers on their faces, put big teepees up, a time of arts and crafts.

Guy Webster:

“The Byrds came to me from Terry Melcher, who was producing them for Columbia Records. I went to the recording sessions for the Turn!

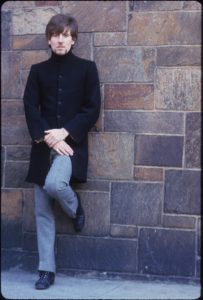

Turn! Turn! over on Sunset and Gower. I didn’t think of them as folk singers, more like rock crossovers. I loved their artistry and sound of the guitars. They came over and I did the session on my big 4×5 Sinar camera. I had them sitting on the ground before this backdrop I’d made. I was getting hip to what would happen to my cover photos; you’d leave space for graphics. I didn’t want my picture to be crunched so I gave them a full bleed with space for the words ‘Turn! Turn! Turn!’ up on top. So I let the blues just sort of drag down to them. It was like they were almost on strings if you look at the photo carefully.

“I was thrilled with it. And it got nominated for a Grammy. I also did some photos of them for publicity and they were dressed for an Edwardian portrait. David Crosby was brilliant but difficult. He’s an Ojai kid. His father was in films. He had a chip on his shoulder. Michael Clarke was so sweet and nice. Chris Hillman – pure musician. We stayed friends. I loved Roger McGuinn’s guitar work and Gene Clark’s voice.

“I shot The Turtles’ Happy Together album. It was a mistake, the worst cover I ever shot. I wasn’t happy because they gave me no time, I had to shoot it outside, and the sunlight was wrong. I had everyone there; Peggy Lipton, my mother and father, my first wife, and all my friends. The band have their arms around each other, happy as clams. And my family and friends are all sullen, seated in the bleachers. I didn’t get the effect I was looking for and wouldn’t you know it, ‘Happy Together’ became a sensation. I just don’t like it as a work of art but the label had final say and they went with it.

“Jac Holzman, who owned Elektra Records, called me on the telephone and said, ‘I have a group I want you to photograph.’ ‘OK.’ ‘Well, they are out at the Whisky a Go Go.’ ‘Alright. I’ll listen to them.’ I didn’t know who they were. I saw them and I liked them, but I was listening to a lot of stuff back in those days. So we had them scheduled to come into my studio, which at that time was located at my parent’s house, in the back. Because even though I was shooting all outdoors stuff at the time, when I wanted to shoot indoors, I had a small studio there. And I wanted to do them in the studio so I could get some very intimate pictures of them.

“And in walked Jim Morrison. And he said, ‘Guy.’ ‘How do you know me?’ ‘Guy, we went to school together.’ ‘Oh my God. Jim!’ We were at UCLA together in the philosophy department and we used to read Nietzsche together. And I went, ‘Shit. I didn’t know you were a singer or a poet.’ I was shocked.

“Here’s the deal on Jim taking his shirt off for the session. Once we realized that we were in school together and that I was already famous with my album covers, I said, ‘Look Jim. You’re wearing this shirt and it’s embarrassing because it has ribbons on it. I know it’s a hippie shirt but you can buy it in Venice Beach and you can buy it anywhere.’ And it would have dated him. ‘I’m gonna take your shirt off. You’ll be alright. Trust me. And I’m gonna make you look like Jesus Christ.’ And that’s what it was. And they went with it.

“I designed the cover and put the other three guys as his eyes and part of his brain. But I made Jim the star on purpose ’cause I knew it could sell the album. Jac liked it and put that on the cover. He always let me do what I wanted for the cover.

“I loved the band live. Oh my God. I later knew that Jim was singing and he had been in class with me. But I was listening to Ray Manzarek’s organ. That was brilliant and that’s what impressed me more than anything. Man, this guy could smoke that keyboard and he was a white guy with little glasses. So I was really impressed.

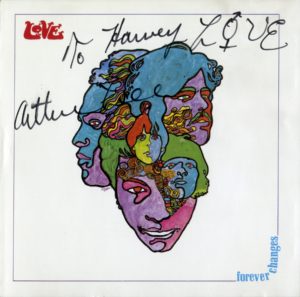

“Love was on Elektra Records. Jac Holzman, the label’s president, called me. ‘I’ll do the back cover for you.’ For their album Da Capo, I made a collage on a large print and photographed the collage. I worked all day in the dark room. That’s done on one exposure, taking all the different single pictures of each of them, placing them on an outline, where they would go. It took me eight hours to get that print. I’d get it once and then one band member would be just out of synch. And I’d have to do it again.

“I shot the band in the studio at my house. I was only interested in lead singer, Arthur Lee. The others I didn’t know about. But I liked that they were a mixed race band. I was part of a generation that thought the world was going to change and we were the ones that would make it happen. Musicians were going to lead the charge.

Johnny Echols:

“Arthur [Lee] started coming to my gigs before he started playing. Because he was a conga player and I would take him around to gigs I played with Henry Vestine and Larry Taylor, before they had Canned Heat. We had a group that played frat parties when we were like age 15. Arthur would hang out and come around. So, he kind of trusted that I knew what I was doing. And one of the things that I learned from Adolph Jacobs was that you’re always supposed to make the singer shine. So what you do is leave room for the singer to express himself and always, always play to the music and not to yourself. If I wanted to I could cut loose on songs and do, you know, a lot of flourishes and stuff that were superfluous really to the music. I chose to try and make the song the king, and the songwriter. The vocalist should shine rather than the other way around.

“If you listen to some of the first songs we did they are rather pedestrian songs. But they were not pushing the envelope. And that happened later after some experimenting and all of that. But the pushing of the envelope happened later.

“Actually, I was not all that enamored with Arthur’s voice for a long, long time. In the beginning the type of music we were doing was not really the kind of music that his voice would shine on. So later on when we started doing his songs and he was writing songs especially for himself. Because he wanted to be a songwriter and have other people do his music. So later on Arthur started to progress. I asked him and all of a sudden he leaps light years ahead of where he was as far as his songwriting was concerned. And he didn’t know how or why and neither did I but I noticed it. And he was pushing me ‘cause I had to kind of push the envelope a bit with my guitar playing in order to catch up and in order to make the music that we were doing work.

“I also then started realizing even more now important guitars and amps were to sound. I met Don Peake at Wallichs Music City in Hollywood and he takes us down the street to his house on Rossmore and he had this 1959 Fender Bassman Amp. He played this thing for us and I noticed the sound of this and Don hooked us up with that sound, because the over driven harmonics and the tubes, that amplifier was probably one of the first ones that really had that blues sound. And so Don hooked me up with that and I went and got one like that. Then I got a Stratosphere guitar. There was this guy out in Hawthorne who was a country music player. I had the Stratosphere but at that time it only had a mandolin neck on it.

“And then I went off to Carvin Guitars, I had their catalog, and got a neck made out there, so I was able to put a 12-string neck on the 6 string and that started me using it. Guys like Joe Maphis and people like that, now he had used them but they didn’t use 12 strings, they were using mandolin and a 6 string. That was the country sound. So I think I was probably one of the first people who did marry a 12 string neck to the 6 string neck.

“I had more options and could play and go between the necks. I could play 12 string parts and then go onto 6 string parts and not have to continue to pick up one instrument and put down another ‘cause I could always keep it in tune. ‘Cause I’m playing then both together.

“In 1964, ’65, we were playing out in Montebello at this place called The Beverly Bowl and we started to develop a large following. And there was a friend across the street, Alan Collins, he had a club up in Hollywood, a gay bar, it was the Brave New World. He said he wanted to switch it over to straight people and asked if we could come there and play. So the first couple of nights we’re there nothin’ but guys there and so, we’re thinking, ‘fuck, we gotta get the hell out of here.’ (laughs). And we would go up to Ben Frank’s restaurant on Sunset and by then we were called the Grass Roots.

“Love had contract offers from MCA (Decca), we were thinking of signing with them, and Columbia, and we chose not too because of the simple reason that Elektra Records was the only company that would let us own our publishing. We learned that from Little Richard. ‘Do not let them take your music publishing.’ So I insisted.

“My role with Arthur and Bryan was basically an ombudsmen to kind of keep these two personalities happening. So I knew that from the very start, because they would have been at loggerheads all the time, because they liked the same chicks, if you listen to some of the songs. That is rock ‘n’ roll. That’s tight, of course, but there was always that strong tension between the two of them and I was always stuck there in the middle kind of keeping the peace but also drawing the best out of them that I could. Because otherwise, you know, Bryan was very much a show tune kind of guy and I knew we could not release show tunes so we had to do a lot of work on his songs to meld then into something that was acceptable to an audience that we were developing.

“Bryan’s ‘Come Softly to Me’ blew my mind. Absolutely. We started putting a jazzy beat to it because Bryan’s songs were very much show tunes and so we had to do a lot, you know, kind of tinkering with the songs to get them to fit in the mold that we were trying to create for Love. Yea, it was conscious and thought out in advance and the way the group looked the makeup of the group. It was never accidental. We decided what kind of group we wanted, what kind of music we decided and what kind of instrumentalists we wanted. We wanted a strong, strong rhythm player, which was Don Conka, who played the hell out of the drums and Kenny Forssi was a very deft bass player. But he didn’t have that heavy low down low bass that you heard on rhythm and blues. He had a really soft touch but it was perfect for the music. He knew what he was doing and we could write it down. We could write charts and everybody could read the charts and play the music and knew what we were doing. And so we thought out what kind of group we wanted.

“I knew we were not doing disposable pop music, because that was the thing about musicians then. There was this kind of this competition to do the best that you could do. It wasn’t just for the money. We wanted to work, get paid, but we also wanted to actually push the envelope. We wanted to play music and we were listening to people that were serious musicians. And we wanted play rock music and do it as serious music like the Beatles were doing. It wasn’t just a C to A minor to F to G. They were playing chords that actually flowed with the music. And that’s what we were trying to do, a different chord structure. Stuff that actually fit the songs and also to try and have an effect on how it was recorded. A lot of time we would get in trouble with the engineer because I would insist in doing it live the way it was supposed to sound and not let them fix it later.