HK: Do you think the big, Winter 2016/17 UGLY THINGS MAGAZINE publication of the career and retrospective multi-page spread on you and your music, and the clips from the 1966 movie, Feelin’ Good, now viewed as a cult classic, were game-changers? Here we are, doing another interview for Cave Hollywood, and the February 10, 2017 Forgotten Hits Newsletter contained our lengthy, in-depth interview on your perspective on the 1967 Summer of Love, which I understand is now posted on all your websites in your Online Interviews and Pictorials.

TP: Yes, especially with regard to my music. Between our Ugly Things interview, and the positive Mike Stax review of my book Odd Tales and Wonders 1964-1974 A Decade of Performance, and my CD catalog, I’ve been rediscovered by some of my old fans, and I’m attracting new ones here, in Canada, Australia, Europe and the U.K. I never imagined that the Feelin’ Good music sequences I posted on YouTube would become so popular. In the UK, State Records is releasing “Watch Out Woman” and “The Way That I Need You,” the two songs I sang on the esplanade on a vinyl 45 in early July, and UK DeeJay Rob Bailey has included “If I Didn’t Love You Girl” in his latest compilation album, and will be releasing a vinyl 45 of it and “The Likes of You” later this summer.

HK: Those recordings go back fifty years or more.

TP: All of that, but in fact, 1967 was a breakout year for me. I went from solo performances in coffeehouses, to creating a group we called Travis Pike’s Tea Party, composing and rehearsing exclusively original material, gaining regional, if not national notice, cutting a record and landing a contract to provide the music for a Boston TV variety show. In the popular imagination, the 1967 Summer of Love is generally equated with sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll. Well, I lived and performed in and through that insanely busy summer, and at the risk of introducing cognitive dissonance, I was too engaged in rock ‘n’ roll, to get much involved in either of the other two, which might explain why my “Boston-birthed unique reflections on the magical Summer of Love” were previously under-reported.

But you’ve done your part to change that. Do you realize that since 2013, we’ve done more than a dozen interviews, and I wrote a sidebar for your book, 1967: The Complete Rock Music History of the Summer of Love. We’ve not only covered the current resurgence in interest in my music, but have been discussing my career right up to the present, with the result that I’m now planning a new book based on those interviews.

HK: And we’ve completed an as yet unpublished interview about your writing, in which you detail your approach to non-fiction . . .

TP: And you may be sure that will be included in the new book.

HK: I should hope so, but non-fiction is just a small part of what you do. You write fantasy adventures too, and one of them, Grumpuss, is composed entirely in rhyme. Song lyrics generally rhyme, but full-blown fantasy adventures seldom do, which begs my question for Cave Hollywood. What is the biggest difference between writing a song and writing a story, or are they all the same to you?

TP: Well, ballads tell stories, as do most novelty songs, so there is some similarity in how they are constructed. For them, it is a matter of setting the story to rhyme and creating a music program that emotionally supports it. Songs may also be inspired by stories on the internet, in newspapers, or TV news programs, and in those instances, you tend to set the story to rhyme, and the melodies, with or without a chorus, are in large part determined by the lyric structure.

HK: When you write songs, do the words come first or after you have a melody?

TP: There are songs you hear with your inner ear, coming half-baked or fully ready to serve. In such cases, it’s almost like re-writing. The song, like a packaged meal, comes nearly fully prepared. All you do is season to taste, unless, of course, by the time you figure out the music, you can’t remember the title. I tell of one such experience in Odd Tales and Wonders. I woke one morning with a song running through my mind, melody and lyrics both, but by the time I picked out the haunting melody and relative harmonies on my guitar, I was unable to remember the all-important hook and title of song. All I remembered was that it was something-stone. I fretted about it all morning, and when the band came over for rehearsal, I played it for them and asked what two-syllable word they knew that went with “stone.” Mikey Joe, the bass player, finally came up with “cherrystone,” and for want of anything better, that’s how we learned the song. When I finally realized that a cherrystone was a kind of clam, I dropped the song from our repertoire.

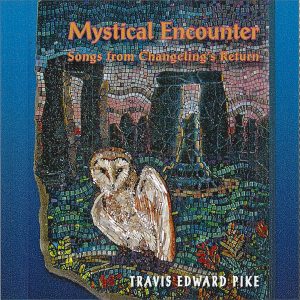

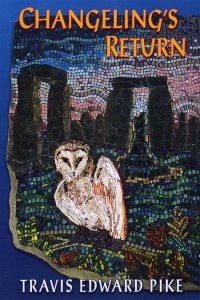

Years later, going through my old song list, I came upon “Cherrystone.” My wife remembered it and asked me to play it for her. As I did, I experienced an epiphany. It wasn’t a vision — more like a forgotten memory. I imagined the sun rising over a monolith in the center of a Stonehenge-like setting, and finally remembered the long-forgotten word, “Morningstone.” You won’t find it in a dictionary, but it was the forgotten word, and for several years, became the new title song for my rock musical, previously called Changeling. But now that I am releasing the screenplay in book form, while the song in the story remains “Morningstone,” the title of the book and screenplay is now Changeling’s Return, which seems to take it full circle, and I’m releasing a new album of the music, Mystical Encounter: Songs from Changeling’s Return.”

Sometimes I write lyrics to a piece of music. “Lovely Girl I Married” and “Only You and Me,” are examples of such melodies from my album, Outside the Box, covered quite well in our Cave Hollywood interview in the Indy Rock section, published June 9, 2016. In both instances, possibly because during their inceptions, other lyrics came to mind that ultimately didn’t survive my process, they were difficult for me to get a handle on, but now, with the lyrics in place, I’m really happy with both.

Just as often, I create music to support lyrics. “Gotta Be a Better Way” and “Friend in Fresno” are songs based on lyrics I had on paper before I began creating music to go with them. Generally, if the lyrics are the most important part of the equation, I keep the music fairly simple to avoid competing with the lyrics, and where the music is complex, I write more simple lyrics. That’s not always true, but generally so.

“Andalusian Bride Suite” is an exception, a really give and take effort. I first composed it as a tone poem, but then added lyrics. The addition of lyrics cried out for more music, which required subtleties and lyrical content to underscore the many traces of the various civilizations that once held sway in that part of the world.

In “Witch,” the lyrics are especially important. The first sequence of lines spoken by the Inquisitor are taken from Tertullian’s sermon on the Apparel of Women, and the Inquisitor’s later lines are culled from actual transcripts of medieval witch trials. I took the roles of the Inquisitors and Karen Callahan, Colleen Stratton, and Lauran Doverspike sang the song. I wanted the music to sonically recreate the 17th Century musical atmosphere surrounding the witch trials of the 30 Years War (1618-1638). My passacaglia is modeled after J. S. Bach’s Passacaglia and Fugue in G minor, (c. 1706 – 1713), but composed in the earlier Baroque form. The ladies’ vocals are sympathetic to victims of the witchcraft delusion, and the sonic lens through which I wished to explore “Witch” is based on Beethoven’s Romantic Period 7th Symphony, Second Movement. (1811-1812), fully two hundred years after the 30 Years War, but practically at the start of Romantic Period literature, which gave us Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein” (1818).

HK: That’s more than the typical answer I expect when I interview a rock musician.

TP: Ask the same question in a week, and I’ll probably have forgotten the specific dates, but the period references will still stand.

HK: When you’re composing a song, do you write the lyrics in longhand or use a word processor?

I generally compose on guitar, less often on piano, but in both cases, I tend to jot down my lyrics longhand. It’s difficult to sit in front of a computer with a guitar in your lap, and try to write on a computer keyboard. I no longer have a piano, so nowadays, I sometimes compose on a midi keyboard, listening to and saving my music on the computer, but I still find writing my lyrics by hand more efficient than switching from the midi program to a word program. Nowadays, I can use an orchestration program to convert my midi files to sheet music, and then enter the lyrics below the staves, but I almost never do. I almost always just type out the lyrics and add the chord changes above them as I go along. With very few exceptions, that’s what I bring to my brother, Adam, who is not only my co-producer, but the multi-instrumentalist, recording engineer, and mixer whose work you hear on all my recent recordings.

I then sing and play the song for him, to establish its rhythm and melody, and we lay down a scratch track, to which we then begin adding all the instrumental parts and backup vocals that make up the finished piece.

HK: So you play both guitar and keyboards?

TP: Not really. Not anymore. I never played keyboards professionally. I just find them especially useful when creating parts. And I hadn’t played guitar for donkey’s years when Adam and I started recording together in 2013. Any guitarist reading this will know that it takes a while to toughen up the fingertips of the left hand to be able to exert enough pressure on the strings to get a clear tone, and to say I was rusty is an understatement. Adam, working in his recording studio, had kept his chops up, and early on, it became apparent that once I established the rhythm, he could play most of the parts cleaner than I. So, with the single exception of songs dependent on my finger-picking style, Adam played most of the rhythm guitar parts that were once a signature in my late sixties performances.

As for my finger-picking, it was almost as painful to hear as it was to play. I have severe arthritis in both thumbs, and you need thumb pressure to fret the strings cleanly, so not only did I have to toughen up my fingertips to be able to hammer on and pull off, I had to endure the pain in my left thumb. The right was even more painful. I use my baby finger to anchor my thumb and finger position while my fingers rediscover and pluck the old patterns they once knew so well, requiring, even after all these years, nearly no conscious input from me. But even finger picking, I would accidently mute adjacent strings meant to sound, and all that right hand activity hurt my right thumb. This may be too technical, even incomprehensible for readers who have never played stringed instruments, but when you’re as out of practice as I was, it’s tough.

Lyric sheets were always the blueprints for my songs. In 1974, I finally took two college music courses. The first was a simple Introduction to Music 101 that taught me musical nomenclature and introduced me to staves, key signatures and notation. I mastered that course during the break between the quarters and when classes did begin, I enrolled in an advanced music course dealing with intervals, and composition, particularly introducing me to modes, in which I had been creating music for years without knowing what they were.

I aced both courses, and would have taken more, but learned that my G.I. Bill was about to expire, because a time limit had been instituted that required veterans to use it or lose it if they did not use it within some new and arbitrary time period. My solution was to go to the college book store, purchase many of the advanced music class textbooks, and continue my musical education through self-taught studies of music history, composition and orchestration.

HK: But when I interviewed you and Adam live, at his studio, you had notated, wide staff orchestra parts spread out all over the room. Didn’t you write that score?

TP: It did. On the day of your visit, we were working on “The Andalusian Bride Suite,” one of the first pieces I wrote for orchestra in the early seventies while I was at CalPoly. Pomona, so it had been some three or four years since I had a band of my own. It was meant to be a tone poem, a Romantic-Impressionistic piece for orchestra. While I was still developing it, descriptions I wrote for myself of things I intended to convey through the music evolved into lyrics and a song was born out of it. I recorded bits of it, just to be sure the parts went together well, but never finished it and had nothing but a rhythm guitar scratch vocal of the song. One day, Adam suggested we look at my old scores to see if there was something we might want to record, and we decided “The Andalusian Bride Suite” qualified.

Of course, the parts were in numerical order, but no matter where they actually entered the piece, they all began on their unique and individual page one. When I began transferring parts to the orchestra staves, they also began on page one, but had nothing to do with all the other page ones. Even after the three-page intro, when I orchestrated the song, it began on page one, but I was clever enough to add “excerpt,” on each of its six pages. As for all the other parts, no matter what instrument it was, or where it entered into the score, every part began on page one.

In my defense, I was used to working with rock musicians, and we almost never bothered with notation. On the rare occasions when we did, Karl wrote the parts and I told them when and where to start playing. When I started writing notation, I probably thought it was only economical to start all the pages with music. If I didn’t need a French horn until section five, I didn’t waste time or paper writing four empty section of rests. I just signaled where the player came in.

I think Adam and I separately came to the same conclusions on the same day. Score pages 1-3 were the intro, page one of the (excerpt) was actually page four of the score, and so on. As for all the random parts, he played them for me and when I recognized them, we were able to insert them where they belonged, and assign them the instruments most likely. It took us several days to unravel the mystery, but now that I am finally able to hear the entire piece together, I’m glad we did it. That experience taught me that if I ever decide to write another score, it will be better to have pages of rests than to lose track of where the music is meant to reside.

HK: We’ve discussed Travis Pike in his early twenties. Now, in your early seventies, with all the documentation, newspaper clippings and career moves, what do you think when see the movies, hear your voice, and see that you are becoming a cult favorite? Doesn’t it underscore your life’s journey as an artist?

TP: More than that, it underscores the reality that my journey is not yet over. This year, I will be releasing a 20th anniversary DVD edition of my 1997 live performance of Grumpuss, and I am currently publishing Changeling’s Return and the album, Mystical Encounter, Songs from Changeling’s Return.

The book contains the complete screenplay, includes a comprehensive non-fiction section with notes on its mysteries, folklore, mythology and supernatural elements, and our introductory interview about the history, development, and surrealistic style of the motion picture musical property in development. And before the end of the year, I hope to publish Then What Happened, a book about my career from 1974 to the present, based in large part on our many interviews over the years.

I then plan to finish those original works dearest to me, that have never been released to the public. My most ambitious unpublished work, Long-Grin, requires a serious full-time commitment. In development since 1961, the tale has fascinated me through all the ensuing decades. And should I complete the novelization of the entire Long-Grin series, I have at least one other intriguing property, lurking in the mists.

HK: Long-Grin is the name of the dragon I met in your office, isn’t it?

TP: That’s him.

HK: Does it feel like this is all about who you were more than a half-century ago, or would you say, since you’re still an active creative player, it is all one big continuum to you?

TP: A bit of both. Most of my original songs do date back to the mid-sixties – early seventies, but in the 40-odd years since, I’ve been working behind the scenes. I stepped out of the limelight in the early seventies, but I never quit the entertainment industries. I don’t expect all this new attention to herald a return to performance, and I have no plans to form another band, but if any of my current releases become hits, I might be persuaded to appear in concert with bands that play my material. After all, I started out by singing pop tunes with bands in bars and dance halls. The only difference between that and this would be that I’d be singing my own songs.

HK: What were some of your favorite live music moments?

TP: In 1959, my very first gig with the Jesters, a high school rock band, at a sock hop in the basement of a Catholic Church in Needham, Mass. We were supposed to get $5.00 for the night, and were paid $20.00, instead, because we drew the biggest crowd the priest had ever seen.

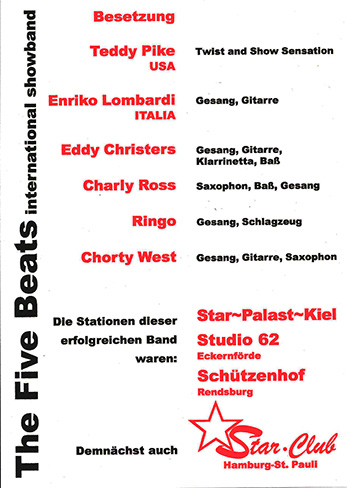

Another was in Germany, at Gasthaus Schroeder, Behrensdorf, with a big dance hall servicing a camping ground, in my first gig with the Five Beats. The band had been assembled for me by breaking up two previously popular bands. At the venue, there was a lot of tension because we had been warned that fans of the members from the two bands who had not been chosen, would come to boo us off the stage. Instead, at the end of the first set, the applause was deafening, and during the first break, one of the former band members, and his fans, wished me well.

At another German gig, far to the north in Eckenfoerde, close to the Danish border, the bass player and I, unavoidably detained, arrived quite late to a hostile crowd. I went on immediately and rocked down the house. The crowd was so excited that the local police, who had been called in to make sure the crowd would not turn into an angry mob, not only enjoyed the show, but looked the other way so the younger kids could stay a little past the normal curfew to hear more. Or was it because the police wanted to stay to hear another couple of songs? Either way, it was a great night.

My first gig back in the States was in 1965. While a patient at Chelsea Naval Hospital, a high school band made up of some of the younger brothers of the original Jesters, asked me to come and sing with them in a talent contest at Natick High School. They knew if I did, they’d be disqualified because I wasn’t a student, but that didn’t matter to them. I hobbled on stage on crutches, did three songs and the auditorium went wild, so wild that my father, who drove to me to the event, decided if I could do that to a crowd of teenagers, he’d put me in his next movie, working title “Rock Around the Hub,” eventually released as “Feelin’ Good.”

Then there was the November 11th, 1967, sold out Burton House (MIT) – Charlesgate Hall (BU) Mixer. In his letter, the vice-president of the Burton House Committee, Jorge A. Romero wrote, “The success of this mixer, one of the most successful ever on the MIT campus, was in great part due to Travis Pike’s group…On few occasions before had the Sala de Puerto Rico witnessed such a crowd.” That Saturday, I had been an usher at my older brother’s wedding in Newton, Massachusetts. I managed to get to the reception for an hour or so, but had to leave early because of the gig at MIT. Of course we enjoyed playing to an appreciative crowd of more than 1600 college students, but for me, the night will be forever remembered because half-way through the evening, my brother, Jimmy, and his bride, Sandy, came directly from their Wedding Reception to dance to my music at that show.

And my first 1968 California triumph. Our first Saturday night at The Posh, a large beer and wine dance club in Pomona, California, we also played our first dance contest. That night, there were eight requests for “Land of a Thousand Dances,” one for “Who’s Making Love,” and one for my Tea Party original, “Oh Mama.” The following Saturday, one couple asked for “Who’s Making Love,” and all of the other nine couples requested “Oh Mama.” That second Saturday night, having my original song requested nine times out of ten, was awesome.

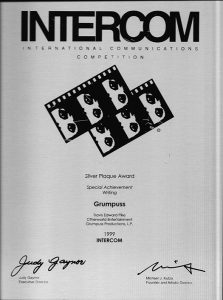

But ultimately, my most memorable gig ever was my 1997, live benefit performance of Grumpuss, in the UK, at Blenheim Palace, a World Heritage site, birthplace of Sir Winston Churchill, then home of the 11th Duke of Marlborough, for the Save the Children Fund. I composed all the music for the show, arranged and conducted by our mutual friend, David Carr. I also performed the entire 99-minute fantasy adventure, playing the narrator and a number of different characters, entirely from memory and entirely in rhyme. Anna Scott played the Queen of the Sidh, and three lovely young waifs, played by Aimee Johnson, Yvonne Hill, and Rosy Meredith, interacted with me in short bits between the acts. As writer, producer, director, and performer, only able to make necessary adjustments during Intermission, I never once got off the stage.

That singular event was both my most exhausting, and my most exhilarating, and the video of that show won an INTERCOM Silver Plaque Award at the 1999 Chicago Film Festival, for Special Achievement – Writing. I call attention to it here, because this year I’m preparing to release a 20th anniversary DVD edition of that live show.

HK: I watched the original VHS production with David Carr, back in 1999, and was amazed by your performance. I’m looking forward to seeing it again, in its new DVD incarnation.

TP: I promise you will, but for now, I’ve got to get back to work. I try to stay busy.

HK: Me too.