Long overlooked, musician, songwriter and now, podcaster, Travis Pike has taken a unique career journey that’s worth checking out.

BY HARVEY KUBERNIK © 2018

I have worked with Travis Pike on my books chronicling The Beatles and The Doors, and he oversaw the layout and design of Inside Cave Hollywood. The Harvey Kubernik Music InnerViews and InterViews Collection VOL 1, published by Cave Hollywood.

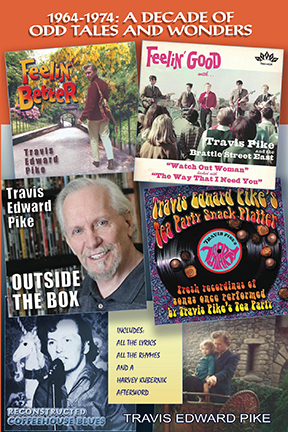

Now he’s published 1964 – 1974: A Decade of Odd Tales and Wonders, a revised and much expanded memoir of the first ten years of his

prodigious and prolific career in music. Having pulled together the Afterword to this new book, I can tell you it’s a

deeper exploration of that era, with many more visuals and artifacts — and I should know. I pulled together the Introduction to his 2013 Odd Tales and Wonders: A Decade of Performance.

deeper exploration of that era, with many more visuals and artifacts — and I should know. I pulled together the Introduction to his 2013 Odd Tales and Wonders: A Decade of Performance.

And in America, he’s doing podcasts for Goldmine magazine, Open Mynd Collectibles internet radio, and being featured in articles and reviews on Forgotten Hits and Cave Hollywood, and in Goldmine, Ugly Things and now in Record Collector News.

Travis, in complete control of his legacy and catalog, recording and releasing albums of audience favorites from 50 years ago, now has record labels contacting him to license and lease his master recordings!

Travis’ first movie title song was “Demo Derby,” arranged and produced by Arthur Korb at Ace Recording Studios in Boston, and recorded by The Rondels. That 28-minute action featurette opened in 1964 with Robin and the Seven Hoods and Viva Las Vegas, before being booked as the “second feature” that played on thousands of screens across the U.S.A. with The Beatles Hard Day’s Night.

Now, a half-century later, at age 74, he’s finding audiences in Europe, the U.K. and airplay on satellite radio. I’m reading articles about him on British blogs like Psychedelic Baby and Fear and Loathing Fanzine, and in British print magazines like Shindig!

Travis had a few singles written between 1964-1974 released independently, a dozen featured in movies, including three movie title songs, and many more never before recorded or released that were part of his original live performance repertoire.

So, while Travis was in Germany, his music was on the same screens with Frank Sinatra, Elvis Presley and The Beatles! That rare Pike Productions recording of the Rondels’ “Demo Derby,” is still sold online, and the Otherworld Cottage Industries DVD release of the Demo Derby 50th Anniversary Edition is available on Amazon.

In 1964, while performing in Germany, Travis came to the attention of Polydor and Phillips Records, but before anything could come of it, he was sidelined by an auto accident that sent him Stateside for reconstructive surgery.

In 1965, his father, Jim Pike of Pike Productions, “discovered” Travis’ talent and starred Travis and featured 10 of his songs, including the title song performed by the Montclairs in the 1966 cult-film Feelin’ Good.

A 45 single of the Montclairs performance of the title song, flip-side by Travis and the Brattle Street East performing “Don’t Hurt Me Again,” while rare, is also still available for purchase online. Travis and the Brattle Street East performed eight of his songs in the film, but until Travis came into possession of a few badly-aged reels from the movie, had them restored at Deluxe, and posted six restored music clips on Youtube, it was believed all were lost.

Two clips of Travis and the Brattle Street East’s performance on the Charles River Esplanade in Boston caught the attention of garage rock fans, and State Records, in the U.K, released the first ever limited edition vinyl 45 of “Watch Out Woman” and “The Way That I Need You” captured directly from the original restored monaural optical soundtrack, that went on to be listed number 3 in Shindig! magazine’s Best of 2017 issue.

Today as his few early singles are commanding big bucks on auction markets, I asked Travis to explain how this came to be, and what it’s like to be getting queries on stuff that goes back before the Beatles came to America!

Q: Your back catalog is reaching new ears and record collectors. Discuss your sixties and seventies work.

A: The songs on the Feelin’ Better CD include seven I performed in the 1966 movie, Feelin’ Good, but re-arranged in my original configuration, with sax, intended for my 1964 German-Italian showband, the Five Beats. A lot of the music on that CD sounds more fifties than sixties, especially “Rock ‘n’ Roll” one of my favorites, and “End of Summer,” which I wrote with German and English verses. Without lyrics, it became the theme for the movie The Second Gun, a feature-length documentary about the investigation of the assassination of Robert Kennedy, nominated for a 1973 Golden Globe. Frankly, I was disappointed when neither of those songs, both personal favorites, were chosen for Feelin’ Good.

Most rare and sought by collectors is the 1967 Alma Records 45 of Travis Pike’s Tea Party’s “If I Didn’t Love You Girl” and “The Likes of You,” recorded at AAA Studios in Boston.

Most rare and sought by collectors is the 1967 Alma Records 45 of Travis Pike’s Tea Party’s “If I Didn’t Love You Girl” and “The Likes of You,” recorded at AAA Studios in Boston.

To date, that Travis Pike’s Tea Party recording of “If I Didn’t Love You Girl” has been released on three compilation albums, The Backyard Patio (Germany), Tougher Than Stains (England) and most recently the 2017 release of le Beate Bespoké 7, also in England.

Travis Edward Pike’s Tea Party Snack Platter is very close to my original mid-sixties sound, especially on rock numbers like “Okay,” “Oh Mama,” “You Got What I Need” and “If I Didn’t Love You Girl,” the “A” side of our only group single release.

In 2003, I met the legendary Geoff Emerick in Hollywood at Capitol Records, where he was producing and engineering The Syrups, the group and the album featuring five songs by my brother Adam and the Syrups’ cover of my “If I Didn’t Love You Girl,” which brings the total up to four albums for that song – five if you count my more recent Tea Party Snack Platter CD.

Q: I can’t imagine what it was like for you around 1964 doing Little Richard material in Germany in front of those demanding audiences, playing up to three in the morning, but from what I hear and read, your songs, ballads and rockers were never wimpy. You were billed as “The Twist Sensation.”

A: The most recent album, Outside the Box, is rooted in the sixties, featuring works I wrote and orchestrated, but never heard until Adam saw the orchestration and decided he wanted to hear it. Thanks to Adam, “The Andalusian Bride Suite” is no longer confined to a file drawer, and may now be heard by one and all. “Flying Snakes” and “Witch” were both composed for my unpublished 1974 rock opera, Changeling, and “Lovely Girl I Married,” always musically exciting, now a song about lasting, mature love, profited enormously from new lyrics. A few weeks ago, I gave Judy a commemorative gold record of “Lovely Girl I Married” for our 50th anniversary celebration. And that album also features “Star Maker,” a recent song by this old retread trying to figure out what he has to do to get traction in today’s market.

Q: I made it to a few sessions of yours in 2013 at Adam’s studio while preparing to write the Foreword to your previous book, Travis Edward Pike’s Odd Tales and Wonders: 1964-1974: A Decade of Performance, your first photo-illustrated memoir of your musical career. In your musical endeavors, there are post 2013 collaborations at Adam’s studio, recording, mixing, and producing, but also your pre-Adam music. There are apples and oranges going on here.

A: True, but most of the songs we’ve recorded I composed and arranged between 1964 and 1974. Few were ever recorded and those few are mostly still controlled by the record companies that released them. My new recordings, released through Otherworld Cottage, date from 2013, and evolved significantly since those early days, in large part to my youngest brother Adam’s technical skill and musical talent, and that’s how my “demo” recordings became masters.

For songs especially popular with my long-ago live audiences, we tried to sound as much like the original arrangements as possible, so Adam’s creative input becomes most clear in Reconstructed Coffeehouse Blues, in songs I originally performed solo, accompanying myself on guitar. To my acoustic finger-picking and strumming, depending on the song, Adam variously added fretted or fretless electric bass, drums, piano, organ, harmonium, electric rhythm guitar, and electric lead guitar. In a nod to the old Travis Pike’s Tea Party version, I contributed a “pop-toy” effect to “You and I Together,” and with Adam’s assistance, created the “instrumental release” to “Don’t You Care at All?” from recorded audio of helicopter gunships, machine gun fire, jet aircraft, rockets, and napalm explosions.

Q: I know toward the end of the last century you wrote a musical screenplay I’ve just learned you nearly got to produce in England in the early nineties. Can you tell me more about that?

A: That property was Morningstone, a rock musical fantasy adventure set in contemporary England’s Midlands and in Morningstone, a parcel of metaphysical real-estate located in the Celtic Otherworld. I’d pre-recorded most of the music, so it was no pig-in-a-poke for investors, who’d be cross-collateralized by the release of a soundtrack album, creating a separate income stream, potentially as large or larger than the box office returns.

In fact, I never abandoned this musical fantasy. Now retitled Changeling’s Return, it’s back on the front burner here at Otherworld Cottage, and I’m working on a book version to publish next year.

Q: I’ve heard the Morningstone Music CD which you’ve now withdrawn from circulation and replaced with Mystical Encounter (Songs from Changeling’s Return) released in 2016. Why has it taken you so long to get around to writing the novel?

A: I had actually started on the novel in 2016, but when the New Playwrights Foundation took a booth at the 2017 Los Angeles Times Festival of Books (the largest book fair in the country), and not one of our presenting authors was offering a stage play or screenplay, I rushed my Morningstone screenplay into print, to show one such work as an example of what the NPF was all about. Unfortunately, the screenplay format did not translate easily into a trade paperback format, and with no time to wait for a proof copy and make any corrections or changes before the festival, it went to press – a hundred copies in all. When it arrived, with only two days to spare, I saw many formatting errors, and even some typos that had slipped by me. I stamped all one hundred copies “FIRST IMPRESSION” and signed them in red ink. What’s worse, I couldn’t even give them away. Apparently, no one at the book fair was interested in reading a screenplay. Fortunately, that meant few people ever saw what a mess it was.

Q: I wrote the introduction the screenplay version, and notwithstanding the formatting issues, and a few typos, it was incredible. I discovered that there was a unique, inspirational journey behind Changeling’s Return.

A: The inspiration came from Rachel Carson’s The Sea Around Us, which I bought in paperback at a Dudley Street Station newsstand in Boston, Massachusetts, back around 1955. For the first time in my life I had lunch money, and had to take the MTA to get to Boston Latin School, so why would I spend 25¢ for lunch, when I could buy a paperback book, read it during lunch period, and on the bus ride home, too? I was 11-years-old. The book brought me to tears. I was afraid that by the time I grew up, the oceans might all be dead. A few years later, she wrote Silent Spring. By then, I was living in Newton and could walk to the library to read it. In that particularly bleak case, DDT eventually was banned, and I began to have hope for a future, but the impact of those two books was with me in 1974; and is still with me today, especially with nuclear waste spreading through the Pacific Ocean, and here on land; honey bees coming so close to going the way of the dodo. Rachel Carson’s writings made an early and deep impression on me, long before the ever-growing threat of ecological disaster became front page news.

It was nearly 20 years later that I began composing my original concept album, Changeling. I had always been concert-oriented, and by the time I began recording Changeling in 1975, everything from Broadway shows to rock musical movies, were on the market.

Q: Hair opened on Broadway in 1968; Tommy, by the Who, was 1969; Jesus Christ, Superstar came to Broadway in 1970; and in 1971, Jethro Tull recorded Aqualung, and that was the same year Godspell opened on Broadway, and Grease opened in Chicago. In 1974, Phantom of the Paradise came to the big screen, and the Genesis concept album, The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway, was released.

A: That’s what I’m talking about. I’d been toying with the idea of a concept album ever since the Beatles Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band came out in 1967. After that, the Beatles stopped touring, but continued to record. For all practical purposes, I stopped performing in clubs in 1969, when Travis Pike’s Tea Party split up, but I was still writing songs, and while I was attending CalPoly, Pomona, I signed up for the first multi-disciplinary program offered there. The idea was to identify and solve the environmental issues facing us all – at the same time I was writing songs for what became Changeling. What I brought to that course was the idea that popular music, which in the sixties had become driven by political issues, could heighten awareness of the environmental issues facing us then, and still facing us today. Creating a concept album, with the potential to become a movie musical, was just my cup of tea. Or perhaps, the beginnings of my “Witchy Stew.”

Q: We’ll come back to “Witchy Stew,” but first tell me about how Changeling got started, why you changed the title to Morningstone, and why you’re now calling it Changeling’s Return. I’m familiar enough with your work to know there must be some significance to the title changes.

A: In 1973, the year I moved into Hollywood from the San Gabriel Valley, The Exorcist did over $400 million at the box office, and in 1974, took home two Oscars. Of course, by then interest in the occult was already sweeping the nation. You mentioned the incredibly successful rock musical, Hair, to which I would add the equally incredible success of the Fifth Dimension’s 1969 medley, “Aquarius/Let the Sun Shine” that topped the charts for six weeks in 1969. People of all ages were interpreting their behavior and the behavior exhibited by their friends in terms of their astrological signs, and Hollywood had a plethora of shops catering to occult interests, particularly in vogue among young people who befriended or rejected new acquaintances on the basis of their astrological signs.

At the Bodhi Tree on Melrose Avenue I found bookshelves stacked to bursting with texts on comparative religion, folklore, mythology, and the supernatural, so my original Changeling, musical, partially recorded in 1975, the story of a 20th century Faust, a young man trying to make time with young ladies by feigning interest in the arcane mysteries, whose occult farce yields unexpected results and leads to the dangers both he and his victim must overcome in their effort to return to our modern objective reality. Although the story has taken an entirely different course, two songs from that earliest effort, “Witchy Stew” and “The Stranger,” survived in the opening sequences of Morningstone and in Changeling’s Return.

Inspired by my occult studies as much as by my environmental concerns, over time Changeling evolved into the story of a contemporary rock star’s out-of-body experience in Morningstone, a parcel of metaphysical real estate where Furies challenge him, Muses beguile him, and Fates still weave Man’s destiny. What began as Changeling is back in Changeling’s Return, more timely than ever, a novel version of the musical fantasy exploration of the ancient mysteries it contains – and must reveal if the human race is to survive.

In Western mythology, a changeling is believed to be the child of a fairy or troll, placed in a human child’s cradle in place of the human child, stolen and taken into their otherworldly realms. Apparently healthy babies, later discovered to suffer developmental disorders were believed by their parents and local villagers to be changelings left in place of their human babies. As for Morgen, whether he is a grown human taken from us and returned as a changeling, or a changeling reared as human, who rediscovers his supernatural roots and returns to our world to fulfill his purpose, the story works either way, and the title, Changeling’s Return further acknowledges that the story’s title and origin have  both been restored.

both been restored.

Q: Changeling’s roots in folklore and mythology aside, you have incorporated many lesser known mystical and occult themes. Where do they come from, and do you think they are more likely to hurt or help you at the box office, if and when the film is made?

A: As for whether the supernatural elements will help or hinder the property, interest in the supernatural has never waned as much as the quality of movies dealing with it. People continue to be fascinated by the mysteries, which is one reason I’m including the section His Mysteries All Revealed in Changeling’s Return. By including articles on the more arcane elements, I’m inviting readers, and ultimately, I hope, moviegoers, to be prepared for the mysteries they will encounter on the big screen. By illuminating them in advance, I hope to present my motives and meanings, which may then still be challenged, but not misrepresented. Carl Jung might have thought it unnecessary, but I got more from reading Robert Graves’ White Goddess the second time, than the first.

In producing and marketing a motion picture, one looks for ways it can be cross-collateralized, and musicals have a built-in source of additional revenue from their soundtrack albums, and with the success of last year’s La La Land, which took home six Oscars from the 2017 Academy Awards, musical movies are again attractive to investors. And I think we can both agree that interest in the ecological challenges we face is currently running high, and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future.

Q: You have always been interested in mystical and spiritual concepts. What are the roots of your explorations in this arena?

A: Strangely enough, I was born en caul, the rarest sort of veiled birth, in which the child comes into the world still completely inside the amniotic sac, thus neither born, nor unborn, neither of this world, or the other. I was an adult when I learned that, so it may or may not have anything to do with my interests and motivations. However, for as long as I can remember I have seen through, or believed I saw through, the exaggerations, hypocrisies, and outright lies of much of what passes today for established history, science, and religion, wherefore I have for many years pursued my interests as an independent scholar. My song, “The Fool” presents my credentials. To write such a song, one must be versed in the mysteries it reveals.

Q: I have found multiple meanings in some of the passages of dialog I read in your screenplay. Aren’t you afraid this will go over the heads of your audiences?

A: It won’t matter. The story speaks as much to the unconscious as to the conscious, and the screenplay is just a blueprint for a movie that will bring its imagery and action to life, allowing its audience to experience it as in a shared dream. According to Jung, dreams speak directly to the unconscious, so what the symbols mean to one, may not be the same as what they mean to another. Furthermore, if one is not ready to cross that developmental threshold the dream embraces, the dream may be dismissed as no more than an entertaining fantasy. But some viewers will give it a second chance, just to make sure they hadn’t missed anything – and that’s what cult films do best. They call their audiences back again and again, whether mentally or physically, to refresh and reinforce their messages.

Q: Did Changeling emerge from a personal dream?

A: No. It was undertaken as a deliberate and thoughtful effort to make audiences aware of the importance of living according to Nature’s laws. Like the hero in my story, I had broken an ankle in an auto accident, and it was during my convalescence that I began writing songs (without my superstar’s advantage of a Midi workstation), but I don’t remember ever dreaming any of the specific incidents and events described in Morgen’s adventure.

On the other hand, some of its songs did sprout from dreams. Both “Morningstone” and “The Likes of You” came to me full blown. All I did was convey them to paper and guitar while I still remembered the melodies, harmonies and lyrics. I discuss them in the Secrets All Revealed section. As I previously said, “Witchy Stew” and “The Stranger” both predate the current story, which is why I place them in Morgen’s show before his otherworldly adventure begins. It may even be that those songs are what attracted the attention of the Muses, and led to his otherworldly adventure. Two other songs in Changeling’s Return have questionable antecedents. “The Fool” is a credential song for a wise man who has to couch his wisdom in riddles to avoid running afoul of an ignorant, hypocritical society, fully capable of turning on him for holding thoughts contrary to their own. A young woman who listened to my earliest version of it, brought my attention to Robert Grave’s White Goddess, thus inspiring my final version of “The Fool,” and a new song to celebrate that inspiration, “Dog, Roebuck, and Lapwing.” All the rest of the music and songs I believe wrote in conscious support of my changeling theme.

Q: When and why did you decide to set the story in a Stonehenge-related community?

A: Before I moved to Hollywood, I finally remembered the title to a song I’d shelved years earlier. That song was “Morningstone.” Sometime later, I discovered Manly P. Hall’s Philosophical Research Society in the Los Felix neighborhood of Los Angeles, where I found, to my delight, a reproduction of The Celtic Druids, a book written by Godfrey Higgins, Esq. and originally published in 1829. It contains sketches and diagrams of ancient Celtic monuments now lost. In 1987, when David Pinto and I recorded the complete demo, with the illustrations from The Celtic Druids and the real-life backstory of the song in mind, I changed the title to Morningstone, and so it remained until I revisited the screenplay in anticipation of this book. Realizing that my character-based title was more to the point, I retitled it Changeling’s Return, which, incidentally, also describes its literary journey.

Q: I’ve heard you describe this as a surrealistic fantasy adventure with big screen possibilities. Why?

A: My works have been compared to the writings of Lewis Carroll, and Changeling’s Return has more in common with his Through the Looking Glass or Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris, than The Sound of Music. In the section His Secrets All Revealed, I shed light on its mysteries, but half the show is an out-of-body experience in a world, where the laws of physics don’t apply, and Fiona is a shape-shifter, perhaps the personification of the White Goddess herself, able to change into a barn owl at will, and travel between the worlds at twilight. She can also transform herself into all three Fates, three Furies, and three Muses, all at once, and in those forms can — and does quarrel with her other selves. That’s why Changeling’s Return has always been intended to be experienced by its audiences.

Q: What drew you to literary and musical development in the first place?

A: My love of literature, music, and movies, all of which come together in Changeling’s Return.

Q: At one time you came pretty close to producing and directing this story. You recorded a music demo, did a script breakdown, budget, location scout, shooting schedule, secured letters of intent from your department heads and even secured a commitment for a completion bond. What happened?

A: It wasn’t just one time. I had been submitting Morningstone to major studios, producers, and independent financiers here and abroad, for funding and production approval, while I worked on other projects for various outside production companies. In July, 1991, I had serious interest from a respected funding group for my three-picture package, Morningstone, Grumpuss, and Long-Grin. They loved the package, but wanted a well-known producer to co-produce the film. I contacted him, but he was more interested in pursuing his own projects. In October, armed with a completion bond letter that said I deserved an Oscar for prep, I contacted the funding group again, and a week later, received a letter saying they were set up for the first quarter of 1992 with funding approved, and were ready to move forward with Morningstone, but shortly thereafter, I was told my funding had again been delayed.

In Late February, 1992, I received a phone call offering full funding from another source, if I shot the entire show in central California, at a significantly lower budget than I had proposed. In March 1992, I took my department heads and scouted in and around Sacramento and Chico, California. We didn’t find the locations we required and could not make the movie for the budget offered, so we declined the offer.

About then, I again heard from the first funding group that they expected to be able to fund me in the third quarter, but that meant I had lost my Spring production window, cast, and staff, so I had to set about putting together a new schedule and budget for 1993. It turned out that first funding group couldn’t meet that schedule either – and that’s when I learned about the collapse of the Japanese bank investors.

I had to scramble around to get work to cover my own operational costs, so I went to work prepping Bo Svenson’s A Spirit Rebellious, a proposed movie about the Russo-Finnish Winter War of 1939-1940. That became the pattern for the next several years. I’d update and revise my schedule and ever-rising budget for Morningstone, then end up scrambling for outside work during the spring and summer months, to cover my development expenses.

I did get close in 1993, with a clear shot at a 1994 production schedule, when John Ferraro, Vice President of Acquisitions at Paramount Pictures, offered me a split-rights deal, based on the talent I had lined up for the role of Morgen. The studio was to put up half the budget for the distribution rights in the U.S. and English-speaking Canada, leaving me with the rights for the rest of the world. With the star I had lined up, I was confident I could easily raise the other half of the budget through pre-sales in the U.K., Australia and Japan, but that deal collapsed when my star’s manager suddenly pulled him from the project to deal with an unspecified medical condition. I didn’t give up on the Morningstone, but other projects kept me busy until now.

Q: When I first interviewed you in 2013, you were planning to rewrite Morningstone as a novel.

A: Yes, and I made three serious attempts to do so, squeezing time out of my busy production schedule, but each time, I foundered on the same rocks. The surrealistic adventure became lost in the telling. Morningstone is a tightly interwoven tapestry. Best-selling books have a fairly direct line to the major studios, but Morningstone was always about an out-of-body experience, and its impact comes, in large part, from its audience experiencing it along with the main character. Back in the real world, when my hero tries to explain himself, the audience will be with him, at least insofar as they have shared that experience, and sympathize with his frustration.

Writers are advised to write about things they know. Well, rock ‘n’ roll performance, motion pictures, myth, folklore, the environment, and the supernatural fall within the parameters of my special interests. I’m writing about things I know, and some of the concepts and constructs I explore in Changeling’s Return date back thousands of years, perhaps to the first humans to recognize themselves as individuals, and still share that tribal sense of belonging to something greater than themselves.

The songs, evocative and crucial to the story, are available on the Mystical Encounter album, but the book must present the story for a reader, not a viewer or listener, although some song lyrics are imperative to an understanding of the action, and move the story along. The text can’t bog down, but must convey enough of the setting, characters and mental scenery to keep the reader enthralled, no easy task when so many inciting events are surrealistic, which is one of the reasons why I will keep the Secrets All Revealed section to help readers explore intangibles not on the page, but hopefully buried deep within the reader’s own unconscious, waiting merely to be called forth. The motto of Otherworld Cottage Industries is, “The World Without Is Not the World Within.” The challenge of Changeling’s Return is to reach that elusive world within.

Q: In 2013 or 2014, you released Travis Edward Pike’s Morningstone Music, an album containing music now attached to Changeling’s Return. What’s the significant difference between that album and Mystical Encounter (songs from Changeling’s Return)?

A: Price and runtime are both reduced. I decided that without the visuals, “Peeping Tom” would be too easily misunderstood, so it was cut from this CD. “In This Place,” the eight-minute procession and dance instrumental, critical to the movie, is not a song, but a thematic, and by not including it, we significantly reduced the runtime of the album by eight more minutes, but if the movie follows the screenplay, then if (or when), the film is made, both will likely appear in its soundtrack album.

Q: You’ve been a composer, lyricist, independent screenwriter, director of production, technical director, dubbing consultant, language adapter, director, singer, storyteller, voice actor, line producer, screen actor, TV director, music publisher (Morningstone Music), president of Otherworld Entertainment Corporation, VP of the Alameda Writers Group in Glendale, California, Chairman Emeritus of the New Playwrights Foundation in Santa Monica, California, (where you continue to contribute to mentoring playwrights, screenwriters and authors), and own and operate a development, publishing, and production entity (Otherworld Cottage Industries) – a “jack of all trades,” a phrase usually concluding with “master of none,” but you’ve managed to get awards and stellar reviews for your work in nearly all of those categories. How do you explain that?

A: I stay busy.

Q: As you well know, myself and others have been watching the renaissance of your early work in music and film going back 50 years and more. You finally managed to salvage some footage from the 1966 rock music movie Feelin’ Good, for which you wrote ten of its eleven original songs, including the title song, and performed eight on screen, but not the title song. How did that happen?

A: My father, James A. Pike, made a deal with the First Massachusetts Jaycees Battle of the Bands committee to offer, as part of the winning band’s prize, a role in his upcoming movie (working title Rock Around the Hub). When the Montclairs won, my father asked me to write a couple of songs for them. I had written the title song to his incredibly successful 28-minute action featurette documentary, Demo Derby. Earnings from Demo Derby provided the start-up funds for Feelin’ Good.

The Montclairs were mostly a R&B group, so I wrote two songs in that idiom for them – and they nailed them. It was their performance of “Feelin’ Good” that convinced my father to change his title. So, while it’s true I wrote the title song performed by the Montclairs, at the time, I didn’t know it was destined to become the title song. That honor, the Montclairs earned with their performance.

When I recorded my 2014 album, Feelin’ Better, it featured updated versions of seven of the eight songs I sang in Feelin’ Good, but not the title song. The Montclairs’ recording is what made it the title song. The performance was theirs, and now that I’ve salvaged that music clip from the movie, I’m glad I made that choice.

Q: When your father produced the movie, he already had a respected reputation in the Massachusetts TV and film community. What in his background led to this movie?

A: Me, I suspect. He said as much in one of the many interviews that appeared in the Boston newspapers at the time. He saw me sing a guest set at Natick High School, and when the student body went wild, it was a revelation to him. He’d never seen or heard me perform live before, and he thought if he could capture that on film, it would be a hit. And, of course, being his son, he knew he could get me to do it for scale.

As for his personal background, he’d been writing radio shows and shooting silent movies in his Roxbury neighborhood since he was a kid. He loved movies and was among the TV executives who came to Hollywood and negotiated getting theatrical movies released to television. He finally realized his dream of becoming an independent filmmaker, and began making industrial films, commercials and political films, until, his 1964 Demo Derby theatrical release.

Q: You now have the 50th Anniversary Edition of Demo Derby in your catalog. KROQ-FM deejay Rodney Bingenheimer and filmmaker Kansas Bowling touted the movie to me after they got a DVD copy. What’s the scenario behind this movie and the music?

A: I wasn’t exactly a hot-rodder, but my first car was a beautiful 1954 Studebaker Commander Coupe with a blown engine. I had older friends who worked in a speed shop who promised to rebuild the engine for me, but rebuilding that Bearcat engine, even with all the free labor, was costing me a fortune for parts, so when those same friends offered to take me around to bars where I could make some extra money singing for tips, I eagerly went along.

I’d only had the car on the road for a week or so when, late one night, driving home from a gig, I came upon a Ford 406 and a Chevy 409 preparing to race at a stop light on Soldier’s Field Road. I casually slid into the third lane for a bit of fun. When the light changed, we all took off. They both beat me across the intersection, but a second or two later, I was gleefully watching them both recede in my rear-view mirror. And that’s when my souped-up engine froze. Worse still, the race had been observed by a Metropolitan District Commission patrol car, and I was ticketed for racing. My driver’s license was revoked, I lost my job, and my car became the property of towing company, so with the draft hanging over my head, I joined the Navy.

Months later, home on leave, my father screened footage of a demolition derby he’d filmed at the Norwood Arena. Even without sound, it was exciting. I suggested he put a rock music soundtrack to it. He told me to knock something out on my guitar to show him what I had in mind, so I did. I was in Germany when I received a DEMO DERBY flyer in the mail. Under the black and white still, the text was “with a music score that will ROCK YOU . . . featuring the sensational DEMO DERBY title song (Travis Pike — Arthur Korb) – recorded by the  RONDELS.” Not bad for something I knocked out in about an hour.

RONDELS.” Not bad for something I knocked out in about an hour.

Q: Talk to me about filming and singing in Feelin’ Good. We’ve talked about the songs previously, but this was a feature film. We don’t hear a lot about the Massachusetts pop and rock music scene, except psychedelia-inspired bands, but you always operated in the modern song format. Singing and crooning. The movie has a cult following.

A: I don’t know that I’d say the movie ever earned a cult following, but I think the idea that there was a movie, made entirely in Greater Boston, in 1966, featuring pop music styles of the times, has created a cult following of people who wished they’d seen it.

When my father began shooting the movie, I was a patient in the Naval Hospital in Portsmouth, Virginia, so all my parts were shot on Saturdays when I had weekend liberty. I’d fly up to Boston, shoot sometimes late into the evening, get up for Sunday dinner with the family and then it was off to Logan Airport, for the flight back to Norfolk, Virginia, and then back to Porstmouth. I had so little time on location that I never had a feel for what the movie was about, or how the dailies I saw on weekends integrated with my scenes. Singing was never a problem, but standing or walking, especially for multiple takes, was necessary, but painful and exhausting, because we had to finish whatever sequence we started on the same day, because the next day, I’d be gone and the location, props, wardrobe and talent might not be available on following weekends for retakes.

Q: I have to ask you about working with the Montclairs. You recovered their footage, along with several of your songs.

A: We filmed the end credit sequence shot on the Charles River Esplanade together, and of course, I saw them again at the Boston world premiere. Other than that, I only saw them in dailies. A major sub-plot of the movie was the Battle of the Bands contest, and in the story, they were our local favorite. Pike Productions shot extensive footage of the actual Battle of the Bands in Weymouth, Massachusetts, so he already had their Battle of the Bands footage when their parts were written. They played themselves, three black singers and three white musicians from Waltham, Massachusetts. The songs I wrote for them, were written after they won. My father wanted their parts in the movie to represent them, their talent, aspirations and dreams, an honest look at the real young people who made up the group. That attempt at cinéma vérité killed us in the South. The Montclairs frequently met after rehearsals and before gigs in a local pizza parlor, where they’d take a booth, order a couple of pizzas and talk.

But 1966 was a tough year in the Civil Rights movement, and it was the year that Stokely Carmichael, Chairman of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, coined the phrase, “Black Power.” In such a climate, a scene of blacks and whites sharing a pizza, where they were not even allowed to drink from the same water fountains, or sit at the same lunch counters might well have been inflammatory to either side of the Civil Rights issue. The distributor who handled Feelin’ Good for the Southern theater chains asked my father to cut the sequence. He didn’t, and so the film was rarely booked in the South.

Q: You moved to Los Angeles in 1968, the year Robert F. Kennedy was slain in L.A. In 1973, you did the musical score to the movie The Second Gun, about the investigation of his assassination. The movie was nominated by the Golden Globes for Best Documentary Feature. What was it like, writing for the screen, as opposed to writing tunes for your group, Travis Pike’s Tea Party?

A: Gerard Alcan, who produced and directed The Second Gun, heard me sing my song “End of Summer” at a Hollywood Christmas party in 1973. He loved it, and said it exactly captured the Zeitgeist of the era and wanted it for his film. When I learned what The Second Gun was all about, I balked. My father had made films for the Kennedys. His film shot the Kennedy Compound in Hyannis Port was used in their campaigns. I even met JFK when he visited our house in Newton, Massachusetts. Part of me feared it might appear I was trying to capitalize on their family tragedies, and I didn’t want the song I’d written for my German fans forever linked to RFK’s murder or that controversial documentary. Gerard persisted and I finally agreed to provide the melody, without the lyrics, and to record additional guitar “stingers” to musically reinforce key revelations in the film. So, although I am properly credited with the score, it was an adaptation of an existing melody, not music I specifically composed for that film.

Q: And you’ve finally recorded and released that song, “End of Summer.”

A: Yes, on the first track of Travis Edward Pike’s Odd Tales and Wonders Stories in Song, with a simple club band feel, and the second, remixed and with the addition of a string section, on the last track of the more recent Feelin’ Better CD.

Q: Between 1974 and the present, you worked extensively in the TV, film and live performance world. And didn’t you once direct Orson Welles?

A: I’ll tell you what happened, and then you tell me if I directed Orson Welles. I had become something of a dubbing guru, having tested the available ADR (automated dialog replacement) digital systems and rated several dubbing studios in the Los Angeles area for Sync Ltd. When Sync Ltd. realized the dubbing assignment they had undertaken for the Italian/Yugoslavian co-production of Wagner e Venezia was a sprocket job, 35mm film elements including the pre-mixed music and effects tracks (M&Es), they asked me if I would do it, since I had experience with film. The narration had been prerecorded, so ostensibly, all I had to do was record Orson Welles for the voice of Richard Wagner, transfer it to one stripe, cut it into the dialog reel, and supervise the final mix. I rented an editing bay with a Kem table, laced everything up and ran through what I had.

The pictures and M&E were excellent, but Orson Welles insisted I had to use a little studio in Hollywood, so I went to see it and talk to the engineer. The engineer and studio were fine, too,but Welles had a list of rules. The first, and most important rule was, I was not allowed to speak to Orson Welles. No one directed the great director. Since I was responsible for getting the performances I needed, I told the engineer I had to talk to Mr. Welles. He replied that if I had anything to say, it had to be said to him, and he would determine whether or not he should pass it along to Mr. Welles. If I didn’t agree to those rules, I wouldn’t be allowed in the studio. I thought long and hard about whether or not I wanted to go forward with the project, but the client had insisted on Orson Welles for the voice of Wagner, and since it was voiceover, with no lip sync required, my razor and I would determine where in the film the great man’s lines would be heard, so if Sync Ltd. insisted, I’d do it. They did, so I did.

On the big night (it had to be at night, another stipulation), I arrived early and had to wait outside while Mr. Welles was made comfortable in the recording booth. I was not allowed to greet him, but did nod hello as I went to the control booth, where I discovered that from where he sat, Welles could see me, and I could see him. Welles reading was spot on, right from the start, but I hung on every phrase like my life depended on it, and smiled when I thought the reading was excellent, and looked a bit less enthusiastic if I wanted something more. And I got it! Welles watched me, and responded to my facial reactions, with second and third attempts at questionable lines. I established the unspoken rules, but kept my facial expressions subtle. Had I gone over the top, Welles might have been insulted, and whatever influence I might have, might be compromised. But I’ll admit I was enjoying myself, wordlessly getting the readings I desired. And in the end, in editing, I cut the lines in exactly where I wanted them for the final mix.

Q: And you had something to do with Ingmar Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander, didn’t you?

A: “Something to do with” is just about right. When Ingmar Bergman brought his five-hour production of Fanny and Alexander to Rudi Fehr to have it dubbed into English, Rudi, in turn, brought it to Betty Givens, President of Lingo-Tech Dubbing Services. Betty immediately called me and asked me to set it all up. My job was to line up a suitable ADR studio, create a schedule and budget the project. ADR had come of age and a film that long, done the old-fashioned way, would have been incredibly time-consuming (and I’m talking expensive studio time consuming), as to be prohibitively expensive. Rudi Fehr directed the Swedish to English dubbing sessions, and I think he replaced the dialog for the entire five-hour show, although it was subsequently cut down to three hours for the U.S. release. I thought I would be producing the dubbing sessions for Lingo-Tech, but Rudi told Betty he didn’t need a producer and that was that. I was well-paid for setting it up, but that was the extent of my involvement, until, when the mix was delivered and accepted, Betty Givens came by Otherworld Cottage, presented me with a bonus check, and thanked me for my excellent prep. The project had come in ahead of schedule and under budget.

Q: You facilitated the voice replacement for the English language version that allowed the members of the Academy to view and understand the film that subsequently took home five Academy Awards.

A: Yes. And thank you. I never thought of it quite that way before.

Q: Wasn’t that about the same time you and our mutual friend, David Carr, produced the long-form music video Ventures in Space for Award Records and Tapes, featuring songs from The Ventures NASA 25th Anniversary LP?

A: Yes. David and I co-produced the show, and I directed it at Conway Recording Studios in Hollywood. David played keyboards on that album, and on screen in the production. Nike provided jump suits, so I had the studio engineering crew and David dress in maroon ones, and put the Ventures in blue ones, going for a sort of Star Trek look. David and I both supervised the video editing, intercutting the Ventures’ studio performances with actual NASA footage.

I’m particularly proud of the shot of Mel looking down through his clear drumhead at the camera below, then reversing the angle to show a shot of a NASA rocket stage separation. I made the shots of the control booth crew look like they were NASA mission controllers, featuring them moving slides and showing the plasma readers springing into action when the music began to rock. I even used footage of one of the Studer, 2 inch, 24 track tape recorders starting remotely and getting up to speed almost immediately, and it looked great when we cut it together. Judy’s still got the LP that all the Ventures signed for her.

Q Let’s jump ahead. At the 1999 Chicago International Film Festival, you won a Silver Plaque, Intercom Special Achievement – Writing Award for a 99 minute, world premiere live to video performance of your epic narrative rhyme, Grumpuss. That show also garnered a slew of great reviews, and you released a Grumpuss 20th Anniversary Platimun Edition on DVD in January, this year. I remember David Carr flew back to England with you to conduct the orchestra for your live performance.

A: David not only conducted it, he and my brother Adam had pre-arranged all the music I had composed for the show.

Q: David Carr, one of the original Fortunes (“You’ve Got Your Troubles” and “Here Comes That Rainy Day Feeling Again,”) was born and schooled in England. Did you bring the rest of your crew from the U.S, or hire local crews?

A: I brought American cinematographer Peter Anderson, because of our established working relationship, and his interest in Grumpuss. He was highly respected in the U.K., where he had recently filmed the 3D short, Haunts of the Olde Country for Busch Gardens, and in whom I trusted to be sure the entire show was shot during the one afternoon, four-hour performance window scheduled. I also brought the American costume designer, the Grumpuss Productions accountant, and Lisa, my daughter and diligent production coordinator. The rest of the crew was U.K. local hire.

Philip Moores, officially my U.K. post production manager, was a long-time friend who had worked with me on several projects here in the States, including Ventures in Space and Fandango, an unsold country-western musical variety show pilot for Cine-Midia International starring Jerry Johnson and the Circuit Riders with special guest star, Barbi Benton. Phil introduced me to Doug Urquart, the U.K. Unit Production Manager, who assembled the rest of excellent U.K. crew. That same year Shaun Moore, the Production Designer, won a prestigious Royal Television Design Society Award for a News set he’d created.

Apart from myself, the Queen of the Sidh was played by Anna Scott, an Australian-born actress then living in Los Angeles. At the time, Riverdance was all the rage, and Irish dancers were suggested for the roles of the three waifs in my production, but chose to go with rhythmic gymnasts. I decided to go with Rhythmic Gymnasts for the Save the Children Fund benefit performance, and called British Gymnastics at the Lillishall National Sport Centre in Shropshire, where, to my delight, I spoke to Vera (Marinova) Atkinson, twice World Champion in Rhythmic Gymnastics, former head of Bulgarian National Television Sports, and then publicist for British Gymnastics. I told her what I needed, why, and asked if she could help. She was thrilled to help, knew exactly where I would find the young ladies I needed for my production, and gave me the contact information for Marion Sands, coach of the Coventry RG club. When we met at a regular club rehearsal, Marion introduced me to her wonderful young girls, had them run through some routines, and won me over on the spot. The three I chose to play my waifs were Yvonne Marie Hill, Aimee Johnson and Rose Meredith. Marion’s daughter, Alitia Sands, a former Commonwealth Games bronze medalist and seven times champion at junior and senior levels, choreographed their routines.

In fact, my previous Morningstone scouting expedition had resulted in numerous excellent contacts in the U.K., who proved most supportive  when I brought the Grumpuss world premiere production to their side of the pond!

when I brought the Grumpuss world premiere production to their side of the pond!

Q: Lynn Redgrave and Rachel Kempson (Lady Redgrave), were among your special guests at the world premiere of Grumpuss. How did that come about?

A: Virtually unknown as a storyteller in the U.K., to get an audience of donors for the world premiere, we’d determined that the best way to do that, was to make it a celebrity event. On the advice of my British crew, I’d contacted the Save the Children Fund, and they were delighted with the prospect – but I had to be vetted by Buckingham Palace. I hadn’t known that the Royal Family were sponsors of that charity. Happily, I was cleared by the Palace, but to attract the high-rollers we’d need for the event, it also had to be staged at a celebrity venue, which eventually led to my arrangement with Blenheim Palace. The audience would be limited to 300 persons and tickets, at £1,000 each, would include the performance, the banquet after the performance, and the opportunity to rub elbows with celebrity guests, all meant to encourage high-rollers to buy in. My wife and I, both fans of the 1966 movie Georgy Girl, wanted to be sure Lynn Redgrave was invited, so I contacted her directly through a mutual friend. She and her mother, Lady Redgrave, were delighted to accept my invitation, and looked forward to an all-expense-paid trip back to England to visit friends and family. Other celebrity guests included the Marquis of Blandford (now the 12th Duke of Marlborough), the Master of Ceremonies for the banquet, Mr. Raymond P. Huggins, MBE, MSM, CdeR, retired Academy Sgt. Major at Sandhurst (Senior RSM post in the British Army), and ultimately more sports and production celebrities than movie stars. And at the beginning of this year, Otherworld Cottage Industries released the Grumpuss 20th Anniversary Platinum Edition on DVD, that I am reasonably sure figured into Otherworld Cottage Industries winning its LUXLife Magazine Global Entertainment Award for Best Audio Storyteller 2018.

The Mystical Encounter (Songs from Changeling’s Return) CD is up on Youtube and currently sold on Amazon and CD Baby. While not a soundtrack album, it is an excellent introduction to the music in Travis’ tale of an American rock star, whose out-of-body experience triggers a sudden and profound commitment to the environment and a dramatic change in his music, its lyrical content, and its purpose. This year’s October release of Travis’ new and expanded memoir 1964-1974: A Decade of Odd Tales and Wonders and with the novelization of Changeling’s Return now on the table, I’m confidently predicting 2019 will be another banner year for Travis Edward Pike’s Otherworld Cottage Industries.

Harvey Kubernik is the author of 15 books, including titles on Leonard Cohen and Neil Young. His 2017 volume, the acclaimed 1967 A Complete Rock History of the Summer of Love published by Sterling/Barnes and Noble. Inside Cave Hollywood: The Harvey Kubernik Music InnerViews and InterViews Collection, Vol. 1, published in December 2017, by Cave Hollywood. Kubernik’s The Doors Summer’s Gone published by Otherworld Cottage Industries in March 2018, and in November Sterling/Barnes and Noble have published Harvey’s The Story of The Band From Pig Pink to The Last Waltz, written with his brother, Kenneth Kubernik.