Harvey Kubernik 2002 interview with bassist of the Rolling Stones

C 2017 Harvey Kubernik

The Quiet One, an authorized documentary about former Rolling Stones’ bassist Bill Wyman, has been acquired by Sundance Selects for the movie’s North American rights.

Oliver Murray is the director. The film in production is a collaboration with the Rolling Stones’ founding member, who was with the band

from 1962-1993. In 1997 he formed Bill Wyman’s Rhythm Kings.

“My life has been an extraordinary adventure,” Wyman said, via Deadline. “The time feels right to delve into the archive and tell my story before I croak.”

Bill Wyman, now 80, kept a daily diary, took thousands of pictures and shot hours of film footage and collected vast amounts of memorabilia. He is the author of seven books.

In 2002 I conducted a 45 minute interview with Bill at the Hotel Oceana in Santa Monica, Ca. while he was in Southern California promoting a coffee table book written with Richard Havers, Rolling With The Stones from D.K. Publishing.

Rolling With The Stones, is a definitive real deal inside story of the Rolling Stones presented and explained by one man who was in the inside looking out at us, Bill Wyman.

The book has sold 300,000 copies worldwide.

Rolling With The Stones was done in conjunction with author Richard Havers, who penned the liner notes to the 2016 Rolling Stones’ album, Blue & Lonesome.

Havers and Wyman previously collaborated on the exquisite Blues Odyssey A Journey To Music’s Heart & Soul.

Rolling With The Stones is a stunning visual tour of Wyman’s personal archive of band memorabilia.

Illustrated with more than 3,000 photographs taken by Bill and some of the world’s greatest photographers, this volume emerges as the one book all fans and casual followers of the Rolling Stones need to own. It’s a large collection, a complete all-access biography of the group that integrates manuscripts, press clippings, copious diaries, stage outfits, instruments, posters, set lists, private photographs and so much more.

Publishers Weekly proclaimed “Wyman’s obsession makes for a Rolling Stones fan’s delight… And thanks to either reams of diaries or marvelous powers of recall unaffected by decades spent in a hard-partying rock band, he provides copious historical and observational data as well.”

The gorgeous design and layout only underscore how potent the elements are. I never thought that a rock ‘n’ roll outfit like the Rolling Stones could be captured on flat page documentation.

Wyman and Havers developed a short hand way of providing research and archive displayed with sensitivity and a lack of ego, rarely found in music books, particularly those about the Rolling Stones. The whole package and compilation is so absorbing, that you sometimes forget the curator and guide was in the band for decades.

No one may write more evocatively about the geography of Rolling Stones and the 1960s music climate than Andrew Loog Oldham, but until this Wyman and Havers teaming, no one had captured the Stones’ rhythm ride with such terrific balanced reporting mixing words and especially striking new visual portraits and images.

Look, aren’t we’re all getting a little bit tired of the current revisionist musical history available, as well as newcomers, outsiders, and non-lifers controlling and governing most of the journalistic, editorial and particularly book publishing decisions regarding our rock and roll bands?

Q: Bill, the materials for this book are mind blow. And I know it barely scratched the surface of your extensive archive.

A. We literally used 1% or 2% of what I have. It doesn’t mean we’re gonna do another nine books, though. (laughs). One was enough. Move on to something else.

Q: What kind of blueprint did you utilize just to get this thing started?

A: Well, I didn’t give him seven million words. What I did, I’d already made for myself for the second book, a skeleton of the main events. When I say main events, it was “Mick flew to Paris on holiday with Marianne Faithfull for the weekend.” That was a main event for me. Next line, “Keith moved from that address to that address.” Then the next one was “we did a radio show.” And I got that chronology right away through from the beginning. And I gave Richard that, and from that he worked out, bless his heart, how many chapters, what we would cover per chapter, and all that. So we laid a skeleton out and then we started to fill it. So Richard would say, “All right, what you got on April 1964?” And I’d respond with “I’ve got 30,000 words.” “All right, we’ve got to get that down to four pages. Or six pages.”

So I’ve give it all to Richard, and we’d go back and forth. Then he’d ask, “How many illustrations you got for April, 1964?” And I’d say “Well I’ve got about a thousand or two thousand scans.” So he and DK would go through them and choose the ones they thought were the most interesting, different, unusual and unknown. And then, we’d barter with them. “No, I’d rather have the picture of me playing the tambourine with the boot.” Or, “What about the picture I took of Keith in the dressing room with his spotty shirt lookin’ at his tie in the mirror?” ‘Cause all my photos have never been published, you see. I took 10,000 photos in my career with the Stones. And I’ve taken reels and reels of movies as well. We were doin’ it that way.

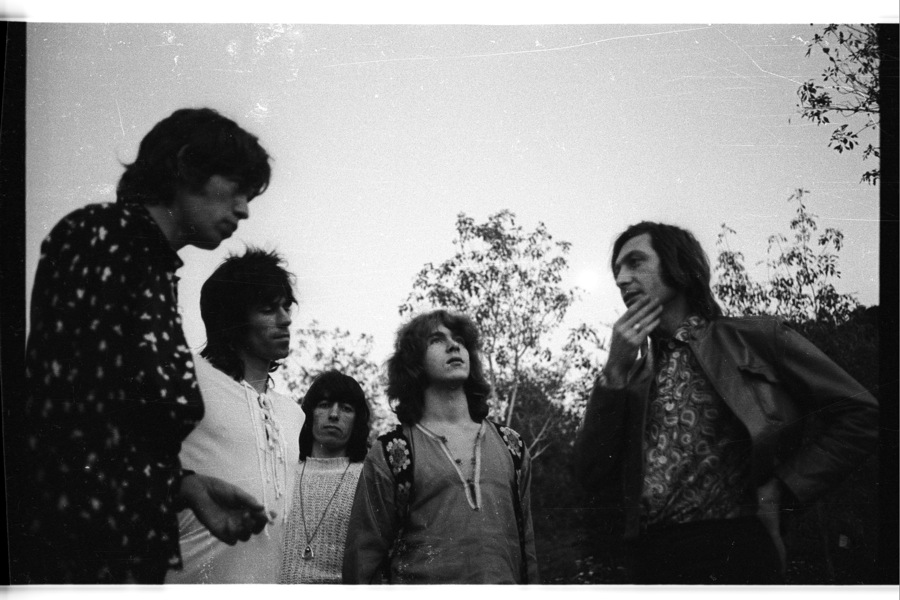

Q: The band always worked well in black and white photos. Who needs color all the time?

A: Yea. Well, our first six years of TV was all black and white because we didn’t have colour in England until 1968. All the shows like READY STEADY GO! were all shot in black and white. The band were a black and white band. They were a mono band sound wise so we always tried to mix in kind of a mono feel. We didn’t have things right out wide on the left and right. It was only the record companies that did that with fake stereo and stuff which sounded bloody horrible in the mid-‘60s. We always tried to mix our sound to sound monish because we liked that sound, that ballsy thing, and everybody else cleaned it up, didn’t they?

Q: Let’s be realistic. It’s a book about a band from someone in the band. How refreshing.

A: Yes. And I could refer to my diaries and get the facts right. You know, you can talk to Mick, and Mick will remember bits and pieces. He won’t always remember if they are in the right years or the right tours, even. He’ll remember bits that I’ve forgotten, probably, and Charlie will as well, but they’re very few and far between.

Q: Your ability to weave in some correctional data in the writings and captions, sometimes contrary to some of your former band mates’ recollections is well documented.

I was pleased to see the factual bass credits for Exile On Main Street on one of the pages that finally correlated to some of my own research. You know what tracks you played on. It’s very obvious. I’ve had other members of the Stones run it down to me as well over the years but not for publication. And the Stones’ CD re-releases and reissues never clear this stuff up.

And, I thought your detailing of the Stones’ visit to Chess Studios in Chicago was so accurate and different than even the way Keith Richards always paints it. This book sometimes is counter to some in-house Stones’ history. Your text has Willie Dixon trying to sell you and the band a song at Chess Studios, and that is not as romantic as Keith describing in the Stones 25 X 5 video seeing and meeting Muddy Waters for the first time when he was painting the walls around the recording studio. That’s bull shit. And I talked to both Muddy, Willie and interviewed Marshall Chess about the Rolling Stones and Chess studios years ago, too. Your diaries underscore the history.

A: The Chess text you refer is different than the way Keith talks about how he saw Muddy painting the walls at Chess. It’s funny. It gets headlines and it gets a laugh. Willie tried to pawn a song on us and Muddy did help us in with the gear. It’s in my diary that day.

Willie Dixon, true. He thought we were naïve white kids who didn’t know these songs. At the same time, when I met Jimmy Reed, when I played with The Heard in South London, Wallington, and met Jimmy Reed. His manager came over and said “I’ve got a great song for your guys. It’s called ‘Big Boss Man.’

We’d been listening and playing “Big Boss Man” for two years and he didn’t know that. He thought, “These white kids won’t know it.” And it was the same with Willie Dixon.

The greatest thing about Chess Records wasn’t the recording, or having Buddy Guy walk in, Muddy, and Chuck Berry coming and saying ‘Swing on, gentlemen, you are sounding most well, if I may say so,” and he knew he was going to make some money. But it was being told we could go down in the cellar and pick some albums if we wanted. Racks of Little Walter albums we had never seen. That was the magic of Chess for us. And me plugging into a plug direct for the bass. Direct!

And I cleared up the bass credits on Exile On Main Street. Because they got them wrong on the album. When I told Mick “I said you got the credits wrong.” And he got pissed off and stomped off angrily because he never checked with me.

Q: It’s like one of my favorite Stones albums.

A: I liked it, but it was slagged off by the critics. When it came out, everybody said ‘the worst album the Stones ever made.’ And five years

later those same people were saying it was ‘the classic Stones album.’ The same people. I’ve got the reviews.

Q: Tell me about RCA studios on Sunset Blvd. and recording albums like Aftermath there?

A: We had recorded at Chess for a couple of dates, a few times. When we came into L.A. we went to RCA. We walked into the studio and it was too big. We were really worried. We were intimidated. We were used to recording in little places like Regent Sound. The studio was like this hotel room. And Chess wasn’t very big either. Suddenly we’re at RCA and it’s enormous. It was like Olympic (in England) later. But we solved that same problem. We thought “God, we can’t record in here. We’re gonna get the wrong sound.”

But Andrew had this brain wave and he put us all in the corner of one room, turned all the lights down, and just tucked us all around in a little small circle. And we forgot about the rest of the room and the height of the ceiling. And we just did it in this little corner.

Like even today, when I play with my ten- piece band The Rhythm Kings we go onto these big stages and we all get in the middle and we put stools up, and we play like a family get together. It personalizes it much more, and as soon as the Stones did that, and got into this little area and started playing, it worked.

And Dave Hassinger the engineer got all the sounds we wanted. Brian picked up all the instruments in the studio. The dulcimers, the glockenspiel, the marimbas. And I played some of that stuff as well. The organ where I laid on the floor and pumped the rhythm for “Paint It Black.” We just experimented in there. Brian brought in electric dulcimers, autoharps. He just did so much to those songs from 1964-1966 in RCA. Brian created so many new sounds. Then he got the sitar together, just so he could play a riff. He wasn’t as good as George Harrison on it. George really learned the sitar and studied it. Brian didn’t, he just picked it up and worked out a little riff for one song. He did it with flutes. And he was brilliant at that. Dave Hassinger helped us do those things and he was always…We never had one bad word with Dave.

At the time we didn’t know the R&B heritage of the RCA studios. All we knew was here was this engineer and on the same thing as we were. Dave used to say we’d just come in and do it. And Nitzsche said it was the first time in his life that he saw a band just come in with no thought or no preparation or anything. He said it in books before. We’d just do it and it sorta blew his mind. Because we had no pre-plans and just do it in three takes. “Let’s do that one.”

Dave Hassinger was lovely. Hassinger was one of the pro-voters for “Satisfaction” being a single. RCA was our first studio that had four tracks. We were on two and three tracks before that. Jack Nitzsche was a sweet man.

Q: I also enjoyed the way you produced the pages and visuals on some departed members like Brian Jones, then Ian Stewart, and a bit on Jack Nitzsche. But they didn’t get extra space or attention because they aren’t around anymore.

A: No, I kind of did that in my Stone Alone giving Brian a chapter. There’s a two- page spread on Brian at the end. Because I do say, and do honestly believe, that if there wasn’t a Brian Jones there wouldn’t have been a Rolling Stones. There would have been another band from Dartford which I wouldn’t have been in and Charlie probably wouldn’t have been in. But there wouldn’t have been the Rolling Stones, because that was Brian Jones.

He named the band and he enlisted the members one by one. He decided what style of music we would play. He phoned and wrote to agents, bookers and NME, Jazz News, Disc, letters about R&B and blues and all of that. I mean it was his band. So I have to acknowledge that or it wouldn’t be there without him. And he’s been kind of glossed over and pushed aside by most people.

And Stew was the second person to join the band. Stew was the first person who joined Brian. Before Mick and Keith.

Q: Bill, the Rolling Stones in concert.

A: The band was great live always. Always. The Stones were a better live band then any other band at that time. I’m not saying they were the greatest songwriters or the greatest recording artists, but they were the best live band wherever you went. You could go up on stage and blow everybody away no matter who they were.

Q: What did you attribute to the live concert experience of the Rolling Stones, besides the obvious chemistry you had?

A: Practice. Doin’ them little clubs in the beginning. Going through all of that learning process, that apprenticeship. Starting off not thinking about being rich and famous and having a career and making a record or going on TV or touring America. Our going out in a limousine like kids think now when they go into a band. None of that. It was let’s play this music and if people like it, that’s a bonus. And if we got a bit of change in our pockets, that was a bigger bonus. And it was that simple. That’s why when we played in the clubs at the beginning we sat on stools, we drank beer, we had no uniforms, smoked in between songs. It was ridiculous. We had our backs to the audience some times. Nobody did that. In a little circle on stage. You can see those early pictures we were all close together.

Q. And always live on stage in concert.

A: I always thought…As long as me and Charlie could got it together, then the rest of the band could do what they’d like and it worked. And that’s what happened in the studio, and that’s what happened live. Me and Charlie were really always on the ball, always straight, always together and had it down.

If we had our shit together we got it right. What he was doing and what I was doing, standing next to him and watching his bass drum, and all that, which a lot of bass players don’t do, stupidly, once we got our thing going, and the group was there, then anything could happen. That’s all there was. There was simplicity. It wasn’t how many notes you played, it’s where you left nice holes and I learned that from Duck Dunn and people like that.

(Harvey Kubernik has been a music journalist for over 44 years and is the author of 10 books, including Leonard Cohen, Everybody Knows, and Neil Young, Heart of Gold. In April 2017, Sterling published Kubernik’s 1967 A Complete Rock Music History of the Summer of Love).