50 Year Anniversary

By Harvey Kubernik Copyright 2020

During July 2020 I had three regional encounters with Doors’ co-founder and guitarist/songwriter Robby Krieger in Southern California. I’ve known Robby for decades and have interviewed him a handful of times.

I saw the Doors in 1968 at the Inglewood Forum and in 2018 Otherworld Cottage Industries published my book on the group The Doors Summer’s Gone. In my last chat with Robby at a gas station in the San Fernando Valley, I wondered if he thought Jim Morrison would be wearing a mask during the coronavirus pandemic.

Robby comically replied, “I don’t think so. Jim would probably want to catch it.”

Afterwards, I immediately went back to my computer and decided it was time to re-visit Morrison Hotel.

On February 9, 1970, the Doors released their epic Morrison Hotel on the Elektra Records label. Ray Neapolitan is the bassist on the sessions, Harvey Brooks is heard on “Queen of the Highway,” and John Sebastian supplies harmonica on “Roadhouse Blues.”

Rhino/Warner Music Group for last quarter of 2020 is preparing a 50th anniversary edition of the album.

Morrison Hotel was produced by Paul A. Rothchild and engineered Bruce Botnick during November 1969-January 1970 at the company’s studio facility located at 962 North La Cienega Blvd. in West Hollywood.

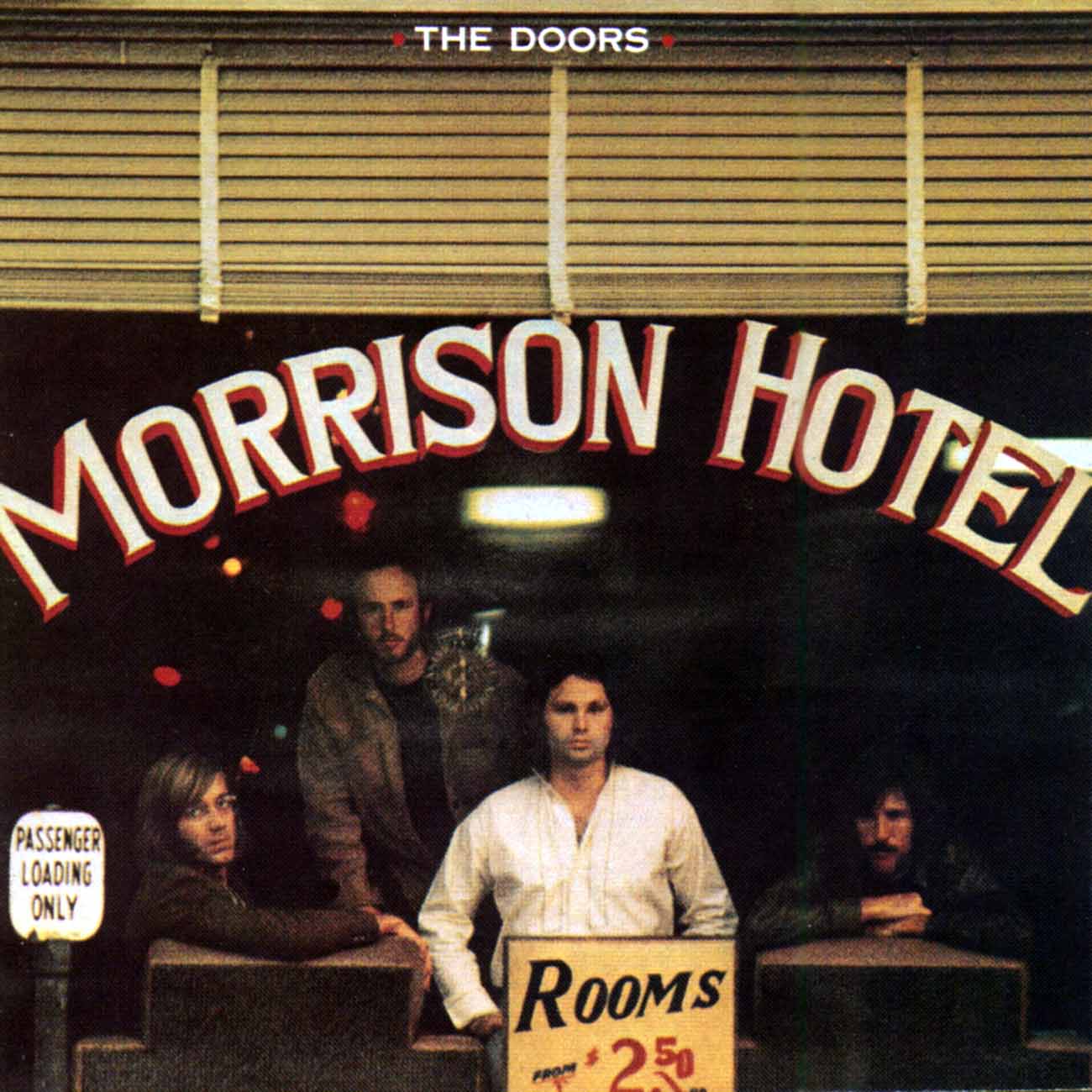

Henry Diltz took the album cover photograph in downtown Los Angeles at The Morrison Hotel located on 1246 South Hope Street and the back picture at 300 E. Fifth Street in the same area.

“The Doors were interesting and weren’t a guitar band,” Henry told me in a 2008 conversation.

“They came from a different place. It was that keyboard thing. They didn’t have a bass. Ray Manzarek played bass on a keyboard with his left hand. It was a little more classical and jazz-oriented. And then you had Jim Morrison singing those words with that baritone voice. It was poetic and more like a beatnik thing. It was different. And Jim wrote all those deep lyrics. I took photos of them at the Hollywood Bowl in 1968 when they did a concert.

“Jim had lived in Laurel Canyon. So did Robby Krieger and John Densmore. We were all friends in the area. I knew him as a musician just as I was first really taking photos.

“I did one day with the Doors in downtown L.A. for Morrison Hotel and got that cover LP picture. Then two days later they needed some black and white publicity pictures and we walked around the beach in Venice.

“Before I shot the cover of Morrison Hotel we had a meeting at the Doors’ office on Santa Monica Blvd and La Cienega,” Diltz revealed to me in a July 2020 interview.

“They had an office in a little funky building and various ideas were discussed and no one really had any. And then Ray Manzarek just said, ‘My wife Dorothy and I were driving through downtown L.A. the other day as we do and we saw this funky hotel.’

“And my partner Gary Burden, he was a graphics artist, and I thought, ‘Fuck! Morrison Hotel. That’s great. Let’s go down and look at it.’ We all piled into a Volkswagen van and drove down that afternoon and saw it in all its glory. That front window! And we took some shots. And a week later we came back with the band. The Doors were always very cooperative photo subjects.

“I used a Nikon camera and a 35 or 85 lens. Gary Burdon usually said ‘Back up.’ In this case he instructed, ‘Get the whole window.’ I went across the street and even shot with a mild telephoto. And it was slide film. [Kodak] Ecktachrome ASA. We got back the transparencies back from the lab.

“Gary then looked at them first, lays it out on a slide board at night, reviews them and makes choices. And then he picks the one. He had unerring taste for picking ‘the one’ that really said it. And I totally trusted him to do it. He was very good.

“He always had exquisite taste. Gary would set up kind of a situation for me to photograph the whole thing, ‘film is the cheapest part,’ he would always say. He would review them all and tell the record company after we’d show the group first. ‘Yea! Fantastic man. ‘Here’s the cover.’

“And now I have a company we named Morrison Hotel. Years ago every month we would go to a different city and have a big pop up show on the weekend. We did that 6-8 times a year and ended up in New York. And we had a store front.

“We were across the street one day and watching people walk by in Soho. Prince Street, like Sunset Strip used to be in the heyday. In the window we had a big blow up of the Morrison Hotel picture. Which is a little wider than the cover of the LP.

“The album cuts off the two lamps on the end. But the picture itself is pretty grand, you know, but when you see it as a print it is rectangular, not square. We would check out people go by, take a look, a glance, and take a step, stop, and walk back and look at that picture. It would grab them. And then, half the time they would walk right in the gallery. We saw this happen over and over again.

“That picture was such a magnet. And then I said to my partner Peter Blachley, ‘Look above at that big arc of red lettering there. On our window we got nothin’. We didn’t have a name for our gallery. On the door was stenciled in small letters, ‘The Photography of Henry Diltz.’ But we did not have a name. We had this photo at the bottom of the window which shows that great writing, and Peter said, ‘You know what? I’m gonna call a painter tomorrow and have him paint that up on our window as an attention getter.’ And, of course, it stuck. It became the name. It’s a perfect name.”

In 2017 I interviewed Jac Holzman about the Doors for my book 1967: A Complete Rock Music History of the Summer of Love. Holzman is the visionary talent scout, A&R man and founder of Elektra Records.

“We had the Morrison Hotel shot but how we framed it was interesting. And [Elektra Records art director and graphics designer] Bill Harvey and I would almost get into fist fights over stuff. But this was part of the creative process. My part of the creative process is to be involved but not buried in the middle to the extent that I lost my perception or position to be able to look at it from slightly afar. So as to determine what we got was what I thought was going to work. Because album covers were important to the sale of music.

“I saw myself as a mid-wife to their music. I think the word channeler is better. They recorded it. I helped supervise how it was going to be taken in and what I hoped would be willing ears. That’s my job. And it’s my job to talk tough when I need too. But I never had that kind of problem with the Doors.”

Holzman did suggest a therapeutic and commercial moment for the Doors when Jim Morrison was criminally charged with indecent exposure and lewd behavior after the band performed on March 1, 1969 at the Dinner Key Auditorium in the Coconut Grove area of Miami Florida. Morrison was facing Dade County jail time in September 1970.

“The only time was when there was much screaming about Miami. I said, ‘if your shows are being cancelled, we will figure something out about how we’re going to bring you back live. In the meantime, go into the studio. Start writing another album.’ And that was Morrison Hotel.

“And then we did two evenings of Doors’ concerts [on Sunset Blvd. in Hollywood] at the Aquarius Theater and those tickets were two dollars. We underwrote the rest. We picked up the tab. But it was there where we launched them. And that idea came from us. That’s kind of what you do when you live your artists anguish and you try and help them and you over the tough spot.

“Morrison died young. Jimmy Dean. That’s part of it. But he lived his life as full and he lived his life without any attention to convention, or what anybody else thought and a flame that bright usually does not burn long.

“I was more impressed by Ray Manzarek at the beginning than I was by Jim,” admitted Holzman.

“Jim had the vocal chops but that persona crept out once he knew he had a safe home or a safe perch to work from. Remember: The Doors were a band that had been signed to Columbia and they couldn’t even get to make a single. And the reason I offered them a three-album guarantee was that I never wanted them to feel that they would get booted out the door if the first LP didn’t sell.”

“I was really excited when we signed to Elektra and Paul Rothchild was going to produce our first album and he had produced Paul Butterfield,” emphasized Robby Krieger.

“Morrison Hotel is often regarded as the Doors return to form after their uneven fourth album The Soft Parade almost sunk under an overload of strings and horns,” suggested writer and musicologist Michael Macdonald.

“Stripped back to the band’s signature blues rock foundations, Morrison Hotel is full of lean grace and solid songwriting. Although the album produced no hit singles there is much to like – Jim Morrison’s state of the nation rant ‘Peace Frog,’ the straight-ahead rock ‘n’ roll of ‘Land Ho!’ and ‘Ship Fools,’ two languid crooners in ‘Blue Sunday’ and ‘Indian Summer’ along with the rowdy blues anthem ‘Roadhouse Blues.’

‘“Queen of The Highway’ housed some of Morrison’s finest lyrics while the slow burning ‘The Spy’ suggested why L.A. Woman happened. Throughout much of Morrison Hotel, there’s a raggedness in Morrison’s voice that adds a certain poignancy to the songs and, although we didn’t know it at the time, he only had one album left in him.

“Morrison Hotel was initially regarded as a new beginning for the Doors but a year later it signified the beginning of the end and that’s why it remains one of the Doors most championed albums. From the iconic Henry Diltz cover shot to the seemingly throwaway, but still enjoyable closer, ‘Maggie McGill,’ Morrison Hotel succeeds on all levels.”

“Despite the Miami disaster in 1969, the Doors released three albums in

1970. 13, Absolutely Live and Morrison Hotel,” underscored Wendy Bachman who started the Doors-centric website Ship of Fools with Kerrin Revell in 2014.

“Morrison Hotel though never achieving a hit single has always been a fan favorite. One reason for this is that it is seen as the Doors returning to their roots. There is more truth to this than many might realize!

‘“Indian Summer’ was recorded in 1966. The track on Morrison Hotel only added vocal and music overdubs. ‘Waiting For The Sun’ was written earlier, though oddly not included on the Waiting For The Sun LP. Lyrics were written by Morrison with music by Doors photographer and confidante Paul Ferrara. Robby reworked the guitar licks (thereby leaving Ferrara uncredited) for inclusion on Morrison Hotel.

“‘You Make Me Real’ was also an early song, dating back to their freshman days at the London Fog club. ‘Queen Of The Highway’ was recorded earlier as well during The Soft Parade sessions.

“Morrison tapped back into his past with songs of a nautical nature. His father being a Rear Admiral in the Navy and a key player in the Viet Nam war.”

“I think of Morrison Hotel in the context of The Soft Parade, which preceded it, and L.A. Woman, which followed it,” theorized poet Dr. James Cushing, English and Literature professor (ret.) from Cal Poly San Luis Obispo.

“The Soft Parade sounds today like too much of a conscious art statement, with its controversial horn and string arrangements, and L.A. Woman is the fullest realization of the band’s symbolist-blues vision since the first LP.

“Morrison Hotel marked the Doors’ return to bluesy form with its focus on song and groove, and works better as a party record almost as well at L.A. Woman. ‘Blue Sunday’ and ‘Indian Summer’ are two of the group’s most affecting ballads. And how many listeners first became aware of Anais Nin through ‘The Spy?’ Yes, in my Doors hierarchy, I would rank the first and last albums as tied for #1, but Morrison Hotel ties for #2 with Strange Days.”

Over the last five decades I conducted a series of interviews with keyboardist Ray Manzarek, co-founder of the Doors. I’m listed in the dedication page of Manzarek’s 1999 autobiography, Light My Fire: My Life With The Doors.

In July 1995 I served as co-producer and curator of the month-long Rock ‘n’ Roll Literature Series held at the MET Theatre in Hollywood. The three remaining members of the Doors reunited and performed “Peace Frog,” “Love Me Two Times” and “Little Red Rooster” during the engagement.

In a 2007 dialogue Ray and I discussed Morrison Hotel.

Q: The Doors arrive at Morrison Hotel. Why this direction?

A: On The Soft Parade we had done our horns and strings experimentation. We had a great time.

“Critically it was our least acclaimed album. However, it has stood the test of time and there are many great songs on there. So, you know what? We’ve done that experimentation. Let’s go back to the blues. Let’s get dark and funky. Let’s go downtown for the album cover. We went to the Hard Rock Café on skid row with Henry Diltz. And we went to a flophouse called The Morrison Hotel. Rooms. A sign read $2.50 and up. It was definitely supposed to be a funky album and you can see that on the inside photo and the front and back cover.

Album covers were always important. We were involved heavily in that process. You could never just turn it over to the record company. Everything that the Doors turned out had to be stamped by the Doors. We approve of this.

Q: There’s a song called ‘Waiting For The Sun’ on Morrison Hotel.

A: We loved the title. But the song had not come together earlier. We finally got it and a beautiful piece of music. It needed to cook more. Sometimes Doors’ songs came out of the collective conscious whole. ‘Bam. That’s it.’ Others needed to cook and theyneeded be worked on. And ‘Waiting For The Sun’ was one of those songs with a great title and the song took a while to jell.

Q: It’s a hard mean album. Morrison’s voice lends itself to this specific material.

A: It was a barrelhouse album and barrelhouse singing. He’s smoking cigarettes. ‘Jesus Christ, Jim. Do you have to smoke cigarettes and drink booze?’ He didn’t say it, but it was like, ‘This is what a blues man does.’ Oh fuck. That’s right. You’re an old blues man. He says that in one of his lines. ‘I’ve been singing the blues since the world began.’ And Rick and The Ravens was a surf and blues band from the South Bay. [The group was an early sixties Manzarek-led band pre-Doors].

Q: How could Jim Morrison write and suggest instruction lyrically in “Roadhouse Blues,” “Keep your eyes on the road your hands upon the wheel,” when most of the time he certainly didn’t operate or drive a car like this himself?

A: Well that was the better Angel. That’s Jim Morrison. Not Jimbo.

“Jimbo was the guy who took Jim to Paris and said, “let’s go and die in Paris. We’re going to have a death in Paris.” Like Thomas Mann’s novella Death In Paris. That was Jimbo.

Q: Morrison Hotel continues the water and ocean themes Morrison previously examined. “Horse Latitudes” and “Moonlight Drive” on The Doors LP. Water is a principal subject referenced in “Ship of Fools.” The ocean and the destination charted in “Land Ho!” and the lyric “River of Sadness” in “Peace Frog.” I’m a Pisces.

A: Always the water. The water is the unconscious, and that’s what The Doors dove into. That’s where LSD takes you: it takes you into the sun, into the light. The fire is the sun, our father in the sky. The watery element is our mother, returning into the womb, diving into the unconscious, swimming around down there to find out what’s lurking below our regular level of consciousness. That’s what opening the doors of perception does.

“Water, ships. It clicks big time. The water images and that beach down in Venice and that ocean side. And the water always entered into Morrison’s life.

“And where does his life expire? In the water in the bathtub in Paris, from the amniotic fluid of his birth to the bathtub in Paris. His final expiration.

Q: Another factor in the Doors’ artistic and commercial journey might also be linked to the military environment that influenced the band. Jim Morrison being the son of military family, and yourself, even before the Doors started, completing your service obligation, serving in Asia and the government via the G.I. Bill paid for your UCLA Film School education. Two of the four principals in the Doors had military ties.

“Unknown Soldier” from Waiting For The Sun was birthed by Morrison’s observations on war. That’s not even counting that the video of the song that was shot at the Westwood Cemetery amongst soldiers’ marked graves. Robby Krieger on Strange Days wrote “Love Me Two Times” about a man going off to the Vietnam War and leaving a woman.

A: The military background gives us a sense of discipline. No matter how much you’ve rebelled against it, you still have the sense of discipline. And the discipline with writing songs is that you get the work done. In the Doors we got the work done. “Let’s do the work.” No matter how much Jim was out there, gone.

“Later on after the fourth album, Morrison Hotel, Morrison completely drunk and out there, he was still disciplined enough to get the work done. To write the songs, rehearse the songs, record the songs. He had the discipline. That’s where the military comes from.

Q: “Peace Frog” was written by Jim and guitarist Robby Krieger. Jim pulled the lyrics from two poems of his in a notebook called Abortion Stories.

In 1995 you told me for Goldmine magazine, “Blood in the streets in the town of Chicago” is obviously about the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago. It was written after the young people rioted against the war, in Vietnam.”

A: Those are great lines. Morrison goes further to say, “Blood is the rose of mysterious union/blood will be born in the birth of a nation.” So it’s the idea that blood is the cleansing property, and from blood will come the healing and the enlightenment of the nation. America is what Jim is singing about. Birth of a Nation, another cinematic reference.

Q: In Goldmine you mentioned a class at the UCLA School of Film you had with director Josef Von Sternberg (The Blue Angel, Marocco, Shanghi Express) who applauded your student film Evergreen. “Very good Manzarek. Very good.” You cited his praise as one of the greatest moments of your life. You disclosed Sternberg’s influence on the Doors’ subsequent recordings and inherent in the way he paced his movies. The psychological weight of his films informed the Morrison and Manzarek wedding of cinema and music.

A: He’s the guy who really kind of gave a real sense of darkness to the Doors, not that we wouldn’t have been there anyway. But having Von Sternberg, seeing the deep psychology of his movies, and the way at which he paced his films, really influenced Doors’ songs and Doors’ music.

“The film school is always there. Our song structure was based on cinema. Loud. Soft. Gentle. Violent. A Doors’ song is aural cinema. We always tried to make pictures in your mind. Your mind ear. You hear pictures with the music itself.

Q: The Doors’ catalog is utilized in a slew of movies and soundtracks. The film school impact is obvious again on Morrison Hotel, especially on “L’America.”

A: It was written for the director Michaelangelo Antonioni for his film Zabreskie Point.

And we played it for him at the rehearsal studio and backed him up against the wall with the volume. We played it the way we normally play and too loud for this elderly Italian gentleman. I could see him pressed up against the door trying to get out of the place. We finish the song, he slides the door open and steps outside and it was almost like he was saying, “Goodbye boys Goodbye Hollywood.” And then he goes with Pink Floyd. It was all too much for him. He just couldn’t do it.

Q: Besides the supplemental exposure a movie and subsequent soundtrack collection brings to one of your recordings and the economic revenue, what do hear and feel when one of your songs is taken out of the original context it was written and recorded in?

A: Here’s what it is from my prospective. This is my relationship to it. It always becomes the matter of the art. The art is the important thing. What is being communicated to the people who are listening to or watching and listening to the art form. You are taking the Doors songs, and the Doors always tried to make those songs as artistic as they possibly could. It was never a commercial attempt, it was an artistic attempt.

“Now, if you take that artistic attempt with the Doors and couple it, the synchronization, you can synchronize that with an artistic vision of images on the screen, that’s the best of all possible worlds.

“Film school guys founded the Doors. When we made the music, each song had to have a dramatic structure.

“Each song, whether it was two and a half minutes or an epic like The End or When The Music’s Over, you had to have dramatic peaks and valleys, and that’s the sense of drama within the Doors’ songs which comes right from the theatre. The point of art is to blow minds.

“The Doors were part of Raymond Chandler, John Fante, Dalton Trumbo. It was the dark streets and The Day Of The Locust, ya know. Miss Lonely Hearts. That’s where the Doors come from.

“Morrison Hotel was definitely blues. Raymond Chandler. Downtown Los Angeles. Dalton Trumbo. John Fante. City of Night. John Rechy.

“You see, nobody came here [Hollywood] to make it. Jim and I came to go to the UCLA film school, and Jim and Robby are natives. Westside boys who surfed for God’s sake. The Doors are L.A., the beach and downtown L.A.”

In my 2007 interview with Doors co-founder John Densmore he cited the impact of UCLA on Morrison and Manzarek, and drum/percussion studio and stage role.

“I wasn’t thinking cinematic, but certainly Ray and Jim coming out of the UCLA Film School were cinematic dudes. That’s for sure. I mean, I hear the world. Filmmakers see it,” observed John.

“Elektra was a good studio. My thing was that I taped my wallet to my snare drum. And then we’d go to eat and I’d leave my wallet and I didn’t have to pay for drinks. (laughs). Not on purpose. Like in the 1950’s drummers used to do that before mufflers.

“In live performances, I had to work harder on the tempo because Ray’s left hand was the bass. And when he took a solo he’d get excited and speed up. ‘Hold it back. Hold it back.’ But, without a separate guy doing bass line runs and grooves there are holes. ‘OK. I’m going in.’ Sometimes I didn’t do anything. That was my territory between the beats.

“I saw Chico Hamilton at the Light House club. There was this ride cymbal riff that Chico did on a song. The ride cymbal on ‘The End’ once I get to the kit and I’m playing the tambourine. It’s Chico Hamilton. That’s where it came from. Chico was direct. ‘Oh that kind of cool cymbal riff I think would fit in that song’ I was thinking to myself, like, going into the bridge on ‘Wild Child.’ That’s the press roll from Art Blakeley. That was direct from the records on Pacific Jazz and World Pacific.

“Let me tell you, at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Doors induction, (Bruce) Springsteen came up to me and said, ‘I like your drumming. It’s so quiet, and then you drop a bomb.’ Thank you, Boss.”

“The last song we did on the Strange Days album was ‘When the Music’s Over,’ Robby Krieger emailed me in 2017. “We had been doing it live a lot, and it was fun because it was different every night, kind of like ‘The End.’ Lots of improvising.

“So the night before we were to record, the phone rings about 4 in the am. I knew who it was. Jim says…‘Robby, Pam and I took too much acid man, you gotta come over. You got to help us.’ I got out of bed and drove over there fearing the worst. They were like helpless babies, not on a bummer, but more just bored.

“I immediately knew what to do. When on acid, always seek nature! They wanted me to take some but I refused. I said ‘Let’s go across street to Griffith Park. It’ll be great!. ‘Yeah. Yeah,’ they were excited! As they started out the door, I said ‘Shouldn’t you get dressed first?’ They agreed and out we went. They were freaking out, having a great time, so I figured they were OK.

“I said, ‘Jim; remember we’re recording tomorrow.’ ‘I’ll be there.’

“Of course he wasn’t. Probably asleep we assumed. What to do? Ray said ‘Let’s just do the track, and leave spaces where Jim does his thing…’ We decided it was worth a try. So we laid it down, trying to imagine where Jim would come in, and other such improvisations that were different every time we played it.

“Finally Jimbo shows up 8 hours late, pretending to have forgotten the 2pm start time… He got it in one take. Amazing!”

The Doors 1991 theatrical feature film was written by screenwriter Randall Jahnson with director Oliver Stone.

Jahnson, like Manzarek and Morrison, are graduates of the UCLA Film School. Other alums are Francis Ford Coppola, Frank Marshall, Alex Gibney, Penelope Spheeris, Paul Schrader, Alex Cox, Charles Burnett, Tim Robbins, Alison Anders, Ava DuVernay, Valerie Faris, Jonathan Dayton, Shane Black, Rob Reiner, Catherine Hardwicke, Julie Dash, David Koepp, and Alexander Payne. James Dean studied drama at UCLA.

In 1972 The Jim Morrison Film Award Fund was established to provide scholarships and fellowships to undergraduates and graduates in the field of directing. It was founded by a donation from Jac Holzman and augmented with donations from Jim’s parents and the parents of his companion/partner, Pamela Courson.

In 2008 I interviewed playwright and actor Jack Larson for my book Canyon of Dreams The Magic and the Music of Laurel Canyon. Larson was happy to share his history with Jim Morrison.

“I was invited by Jim Morrison to Universal Studios to a projection room to see footage shot of their 1968 tour. Jimmy had invited me and [director/producer] Jim Bridges in ’68 to see the Doors at the Hollywood Bowl. He got us great seats but during ‘Light My Fire’ the audience started throwing firecrackers and books of matches. I liked it but I knew by that time that he was unhappy with the whole scene.

‘The guy I saw in the projection room and at USC [University Southern California] was totally different than the one in front of 18,000 people at the Bowl. By that time I knew him and realized why he was so disgruntled. He would talk about Rambeau. He had a beard then, gained weight, and quiet.

“In February 1969 I saw the Living Theater on the campus of USC at Bovard Auditorium with Jimmy. Le Living. We went together. They all exposed themselves. I found Jimmy to be very genuine and I liked him very much. I had a play at the Mark Taper Forum. A group of one acts with playwright Harvey Perr. He wrote for The L.A. Free Press and he knew Jimmy Morrison. And Harvey had this play and we were on the same bill at the Mark Taper and Morrison came down with Harvey and I got to know him. He was enormously friendly to me.

“The irony about Jimmy Morrison is that I’m part of an award at UCLA that is given out, [Jack Larson Award In Acting] that The Bridges/Larson Foundation established that is given out to a filmmaker.

“I go to this awards ceremony and about five years ago there is a James and Pamela Morrison award,” Jack marveled. “I then ask the development woman, ‘what is this?’ I knew Jim went to UCLA and the film school. Pam’s family had established a James and Pamela Morrison film award.”

During 2017 I interviewed Randall Jahnson about the Manzarek and Morrison UCLA campus experience.

“Ed Brokaw had the reputation of having been Morrison’s favorite instructor—at least according to Jerry Hopkins and Danny Sugerman in No One Here Gets Out Alive. That may or may not have been true—but I do know that when I met Ray Manzarek for the first time, we talked about Brokaw and Ray spoke of him in an almost reverential tone.

“The fact that we’d both taken his classes—albeit a good 15 years apart—immediately established a bit of a rapport; it might have even helped me land the job of writing the script.

“Lou Stoumen published a book in 1988 titled Journey to Land’s End. It’s a poetic, loose narrative illustrated with 90 of his black and white photos (Ed Brokaw and Lou’s office are the subjects of two of them). He subtitled it ‘a paper movie.’ On the back cover are endorsements from Laura Huxley, Ray Bradbury and Ansel Adams – not a bad fan club. Recently, when I cracked it open and read some of its passages for the first time in years, I was reminded of Morrison’s The Lords and New Creatures – not so much for its similarities in cadence and observational musings, but its aesthetic, its vibe.

“Of course, Stoumen’s book came out many years after Morrison’s – and one could argue who influenced whom – but I suspect that Stoumen’s post-Beatnik, early-‘60s sensibility made an impact – however large or small – on that pudgy kid from Florida.

“If the film school had a keystone, it was Ed Brokaw. I doubt there’s anyone who went through the program who’d disagree. Taking his editing class and cutting on the Moviola an action sequence from Gunsmoke were a rite of passage. He possessed an encyclopedic knowledge of all aspects of filmmaking. From what I understand, it was Brokaw who really conceived of and shaped the school’s curriculum so that everyone who graduated would be a complete film maker.

“Like Stoumen, he was a WW2 veteran. He had served in the Army Signal Corps in Burma. After the war he attended the UCLA film school and graduated in 1952, then joined the faculty. He taught there a couple years then moved to New York and ran his own production company. In 1961 he rejoined the UCLA faculty and stayed until his retirement in 1988.

“His lectures could be meandering esoteric excursions incorporating the work of John Cassavetes, his wartime experiences, close encounters with John Coltrane and Miles Davis (he was a big jazz fan), and the grain count of a specific film stock.

“When I interviewed him in 1986, Brokaw was 69 years old and Professor Emeritus. I met him at the North Campus area of UCLA. We spoke for about an hour. He described Manzarek as very cinematic in his thinking, a natural film maker. Morrison, however, was not. His ideas were too abstract, too complex to translate onto the screen. That’s why poetry was a much better form of expression for him.

“Brokaw led me to a nearby patch of grass and proceeded to walk off the exact dimensions of Bungalow 3K7, the Quonset hut that had once stood there, housing the film school at the time Morrison and Manzarek had attended.

“Next he vividly described its interior. He finished by pointing out where the port-a-potty that serviced the department had been erected. On the inside of its door, he recalled gleefully, was a graffito that read, ‘Jim Morrison has the ass of an angel.’ He said after Bungalow 3K7 was torn down, the door to that crapper mysteriously appeared in the lobby of the film school’s new building, Melnitz Hall. It lasted there for a while – perhaps as a waggish tribute to the school’s famous alumnus – before it disappeared forever.

“Two things come to mind as I think about this. I remember Lou Stoumen discussing Apocalypse Now in class right after its release (he’d also had Coppola as a student). He felt it was a flawed film. On the whole, it couldn’t measure up to the brilliance of its beginning.

“Secondly, I recall Manzarek telling me that he read an early version of Apocalypse Now by John Milius that used ‘Light My Fire’ in the opening sequence instead of ‘The End.’ It described Willard and his squad rising out of a rice paddy to ambush a unit of North Vietnamese. They return to base, hoisting the scalps of their enemies. Willard yells, ‘Hit it!’ and ‘Light My Fire’ begins to play over the base loudspeakers as a kind of victory celebration. Vintage Milius. Ray thought it was very intense, but liked it.”

Author, musician and Laurel Canyon resident Jan Alan Henderson in 2015 sent me this anecdote about his encounters with Jim Morrison when Morrison Hotel was created.

BRIEF ENCOUNTERS WITH THE LIZARD KING

Growing up in the ’60s above the Sunset Strip was an experience that defies description. In those days, everything was possible; the world of music had just turned the real world upside down.

From 1965 to 1970, the Sunset Strip was my nocturnal home. I remember seeing Ray Manzarek, Robby Krieger, John Densmore, and the late Jim Morrison at the Whisky a Go Go before their first record came out. At that time, music was basically tribal dance music, but that night my 15-year-old world was turned inside out, and I was led to the Doors of Perception. The band I saw in my head from the sidewalk that night had a depth and presence that had never been seen in rock & roll.

I remember walking into Gazzarri’s midway through one of the Doors’ sets, and then a year later witnessed the phenomenon that the band had become one magical evening at the Hollywood Bowl. But none of this prepared me for my next encounter with the Doors—or I should say, A Door.

The summer of 1969 I walked into Sunset Sound looking for a job. The first person I saw at the studio was a guy named Brad Pinkstaff. He was an apprentice engineer, the job I had hoped to get. We became fast friends, and I became his unpaid assistant, and worked on projects with him—Lord Sutch and His Heavy Friends, to name one.

One day I walked into the Sunset Sound complex and someone said to me, “We need a vocal mic in Studio No. 2.” So I went in and set up the mic, and walked out to the open-air foyer. There, waiting for his call to put vocal tracks down, was Jim Morrison, with a gallon bottle of Red Mountain wine; a vocal overdub for Morrison Hotel.

Now, I had heard of Jim’s antics, but this afternoon the Lizard King was nowhere to be found. Instead, I sat with Jim, had a Styrofoam glass of his wine, and talked about everyday things. He wanted to know about where I went to school and what my plans were. When I left the studio a short time later and walked down Sunset Boulevard, my feet weren’t touching the ground, let alone the earth.

Somewhere in the span of the next 12 months, I was once again car-less. I was standing at the intersection of Lookout Mountain and Laurel Canyon with my thumb outstretched over the curb, below the traffic light. An American-built muscle car pulled up at the red light. “Get in,” were the magic words as I slid in the passenger side and the light turned green. The driver was full-bearded and resembled a Northern California mountain man. I didn’t know this guy from Adam, but it was his voice that caught my ear.

Then it hit me. I was sitting next to Jim Morrison. Not the Jim Morrison who mesmerized us at the Hollywood Bowl in July of 1968, when we pulled our usual admission stunt. (We’d walk to the end of Primrose Avenue off Outpost Drive, and crawl down the hillside and drop down to the back rows of the Bowl, blending in and taking whatever empty seats were available, steadily moving forward in the historic venue.) As he drove toward Mulholland Drive, I wondered what the future held for both of us. Little did we know that the Lizard King’s time on the third stone from the sun was limited!”

“As an inquisitive teenager with a wandering mind, I used to love to look through the Los Angeles Free Press, the infamous, radical, underground newspaper of the 60s,” author and pop music historian, University of Southern California graduate Gene Aguilera emailed me in summer, 2016.

“One day, there it was . . . a small ad saying the Doors were coming to the Aquarius Theater on July 21, 1969! Elektra Records, the Doors label, had begun a policy of renting the venue on Monday nights (this being the dark night of the play, Hair) to showcase their roster. Naturally, I had to go, but was without wheels at that point; so after much begging (my 16th birthday was coming soon), my aunt, Julie Gillis, agreed to take myself and my two cousins to see one of my favorite bands.

“As we departed East L.A., making our way towards the Sunset Strip, my aunt Julie began to worry about taking her 11-year old daughter, Debbie, with us. Just a few months earlier in Miami, the Doors lead singer Jim Morrison had been arrested for indecent exposure on stage. She said, ‘What if he takes it out again? I don’t want Debbie to see any of this.’ But it didn’t matter to me, there was no other place in the world I would rather be.

“With a painted psychedelic exterior and an exquisite art-deco interior, we had arrived at the Aquarius Theater and sat about halfway up from the stage. With the band still reeling from the Miami bust, an aura of danger lurked thick in the air; when suddenly to the stage strolls a dwarf (adding to the circus-like atmosphere), named Sugar Bear, to announce the band, “Ladies and Gentlemen . . . the Doors!” We were now ready for The Lizard King.

“Jim Morrison looked so much different in person than the album covers I had studied; he arrived with sunglasses, a thick beard, and a paunch around his waist. But for this hometown ‘live’ recording (resulting in some tracks for the Alive, She Cried Live LP), Morrison introduced an edgy new trick to his usual theatrical drama. With the spotlight on, Morrison appeared incredulously high-up in the rafters, grabbed a rope and swung to the stage, Tarzan-style, leaving the entire crowd gasping at what they saw.

“My aunt Julie had her coat ready to cover Debbie’s eyes (if Jim was going to whip-it-out, as he allegedly did in Miami), but that never happened, thank God; Morrison instead throwing Styrofoam balls out to crowd. In my youthful excitement, I ran towards the stage and caught a few. A pretty hippie-girl next to me was disappointed at not catching anything, so I gave her one, and in turn, she gave me a great, big kiss; witnessed by all my group. This was the dawning of the Age of Aquarius.”

“The day before Neil Armstrong walked on the moon, I was at the Aquarius theater with my Barnes and Barnes partner, Robert Haimer, seeing the Doors,” musician/actor songwriter Bill Mumy enthused to me in a 2017 recollection.

“We attended the early show and we got there early and secured seats in the very front row. The gig was great. Morrison was focused and low key but he was a mighty force. I thought he looked great. Thick beard, Mexican peasant shirt and orange Aviator sunglasses. Ray wore a white t shirt. I took several photographs during the gig and have one of the few pics of Morrison onstage looking directly into a camera lens.

‘“Celebration of the Lizard,’ ‘You Make Me Real’ and ‘Soul Kitchen’ were highlights for me. The Doors were such a unique band. To this day, I appreciate Morrison’s poetry and lyrics. He was a genuine artist. They all were great and had musical styles that were/are instantly recognizable.

“I consider myself fortunate to have been there.”

Longtime associate, writer/editor Daniel Weizmann, a graduate of UCLA’s Creative Writing program emailed me about the Doors in summer 2017.

Motel Money Murder Madness: Jim Morrison and the Noir Tradition

Some like to make fun of Jim Morrison for his poetic ambitions — he was young, ultra-serious, and at times he had the somber college student’s yen for Hamlet-like navel-gazing. What’s more, like Michael Jackson and Elizabeth Taylor, the force of Morrison’s stardom at times threatens to overshadow his artistic gifts. Patti Smith recently wrote that she felt “both kinship and contempt” watching Morrison perform. But Jim Morrison’s lyrics did introduce a whole new and highly literary sensibility to pop music — the southern California noir of Raymond Chandler and the southern gothic tradition of William Faulkner. And pop music has never really been the same since.

Of course, new things were already happening to the song lyric before Morrison made his move: Dylan shocked the airwaves with Biblical passion and Whitmanesque frenzy. The Beatles followed with colorful utopian imagery that had roots in James Joyce, Lewis Carroll, and Edward Lear’s nonsense verse. But nobody brought the gravity, the hard realism, and the psychological pressure of noir to the popular song before Jim. As Lester Bangs famously put it, “The Stones were dirty, but the Doors were dread.” That dread represented a major leap toward adulthood in ’67 and the boomers flipped for it. After a youth saturated with sunshine and goody goody gumdrops consumerism, they had secretly been craving just such a counter-move.

As Pete Townshend put it, the success of “the Doors…just seemed to be meteoric and sudden and absurdly huge. Jim Morrison’s Christ picture was all over fucking New York.” The first album’s shadowy album cover and billboard, shot by Joseph Brodsky (?), was a knowing nod to noir film posters like “Out of the Past” and “In a Lonely Place.” And Jim’s crooner voice and movie-star good looks defied the rock template, as well. But most of all, the words, their impressionistic, nightmare-like alienation, were strange and yet instantly recognizable. Realms of bliss, realms of light, the days are bright and filled with pain, ride the snake to the lake, all the children are insane — this was a long way from “Wooly Bully” and “Palisades Park.”

We can’t know exactly what inspired Morrison to fuse the noir dreamscape to the popular song… but he was a military brat, raised in Florida and New Mexico. The south, with its backwoods quiet, its open highways, its malevolence, and its anti-culture, was in his bones.

Throw a UCLA dose of Nietzsche, Rimbaud, the exotica of eastern philosophy, Jungian psych, and the Native American tragedy into the mix, and you’ve got a potion powerful enough to challenge the lyrical norms as deeply as the sound of Hendrix’s guitar did.

As Joan Didion — herself a star student of Hemingway and Chandler — wrote in The White Album, “The Doors were different…(they) seemed unconvinced that love was brotherhood and the Kama Sutra. The Doors’ music insisted that love was sex and sex was death and therein lay salvation. The Doors were the Norman Mailers of the Top Forty, missionaries of apocalyptic sex.”

One of the last of the Venice Beach beatniks, Morrison self-published slim volumes of verse, even at the height of his rock stardom. In a radio interview, he said, “Eventually I’d like to write something of great importance. That’s my ambition—to write something worthwhile.” Did he pull it off? He certainly had a hard time straddling his roles as shaman, youth leader, pop icon, and serious artist. But he struggled in earnest, and it’s impossible to talk about the Los Angeles tradition that stretches from Chandler, West, and Fante to Didion herself, Bukowski and beyond, without seeing Morrison’s part.

What’s more, for better or worse, whole music genres have Morrison to thank for forging darkness to the pop song. Bowie’s Berlin Trilogy, post-punk, and even grunge couldn’t have happened without him. Some, like the Cult, seemed only to get the histrionics; others, like Jane’s Addiction, reached harder for poetry but lacked the warmth of Morrison’s voice. Because, in the end, despite the shaman poses, the billboards, and the spotlights, Morrison really portrayed himself as a lone human, in true noir fashion, struggling through the night. He wrote from the personal inner space that is poetry.”

Earlier this century Manzarek and I discussed the durability of the Doors’ sound that still resonates today. He touted producer Paul A. Rothchild and engineer Bruce Botnick.

“Rothchild and Botnick are Door number 5 and Door number 6. There’s four Doors in the band and two Doors in the control room. So, they were always there, always twisting the knobs and really on top of it. A couple of high IQ very intelligent guys. We couldn’t have done it without them.

“The Doors. Pure serendipity. It was an energy of the time. Morrison had a great line, ‘in that year we had an intense visitation of energy.’ Those years lasted from approximately 1965 to 1970. The psychedelic generation had come of age. The young people had come of age. We were the fruit of the American dream. We had everything. All the education and all the pampering. Low and behold, we are all one with everything. Everything is one with us. We, especially the hippies, are all each other’s brothers and sisters. Now let’s become artists and let’s see if we can change the world. Let’s see if we can take love and make love change the world.

“So, what happens with the playing of Doors’ music you enter at a lower state of consciousness into an almost hypnotic state and at the same time an elevated cosmic state of consciousness. So you are comically aware and you are hypnotically down into the vibrations, the energy of the telluric force, the energy of the planet, the energy of the thousand miles an hour spinning globe that we’re on. With that hot molten center you’re part of that and you’re part of the infinite cosmos at the same time all in playing your music. And that’s what Doors’ music is about. It’s right there.

“It is a collective journey that’s a good way of putting it. It’s of course Jim Morrison as the charismatic lead singer, and I’ve got to address Jim Morrison, but it’s [John] Densmore, Krieger and Manzarek (too). It’s a journey of these four guys, The Four Horsemen of The Apocalypse, the diamond-shaped, no bass player that made a five point pentagram, shape of the diamond. It’s the inverted pyramid. It’s an archetypal journey of four young men into the unconscious, and coming out of that and creating a musical art form. We were working in the future space. And many things have come to pass that Jim Morrison wrote about.”

Greg Franco, bandleader of Man’s Body, is a UCLA graduate in History. Greg is the son of Doors mega fan Gilbert Franco, 1935-2006.

During 2014 Greg emailed me about the Doors.

“I was purposefully walking down Chapel Street in Melbourne Australia going to our Rough Church gig Wednesday right before Easter in 2012. Being in a city new to you, playing your original music was the kind of experience one hopes for in a lifetime.

“For a brief moment I stopped outside a bar where there was a movie projected on a screen. The movie looked cool. It was in black and white, and there was a band playing on the screen.The shot switched to this guy being interviewed. I snapped a photo figuring it was a cool thing to capture. I filed it away in my mind: Chapel Street, Prahran, Melbourne Australia, 2012.

“A year later at home, I looked closer at my ‘artier’ trip photos, and one was of this guy being interviewed. It was Ray Manzarek. It hit me like a ton of bricks, wow. Ray had just died. It seemed an important coincidence.

“There is this fascination with Jim, and I get that. Everyone was into Jim. If you were a dude from his generation, you had to see him as he was the most fascinating people on the planet. He was a shaman, a sex god, a total mess, everything. But as I got older, and I saw how this all played out, Ray became the focus.

“No doubt the Doors needed a muse man, but they also needed a focused genius to make rock history.

“Ray went on to produce X’s first album, and that is a musical touchstone of my generation. If you think you know something about Los Angeles rock music and you don’t know this album, then you are sadly out of touch. X’s Los Angeles was my generation’s wakeup call; let’s burn all the classic rock records now! (but never the Doors records.) Ray figures into that important musical history. Hell, he played his ass off on that record.

“The Doors are the best band from this town, with a little plug for X, the Minutemen and Los Lobos. The Doors are our tribal elders were heady art and film guys with burning dark souls. They got down with badass beat poets, psych rock, blues and jazz. They built that legacy for us out of the Los Angeles soil, sand and rock.

“They changed music for all time.

“Why did this happen? It’s just in the water baby. Los Angeles is a Mecca. We have our glorious heroes, and it will always be that way.”

(Kubernik is the author of 19 books, including Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon, Ray Manzarek penned the introduction, and Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972

Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and brother Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. For 2021 they are writing and assembling a multi-narrative book on Jimi Hendrix for the same publisher.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in mid-July 2020 published Harvey Kubernik’s 500-page book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters, featuring Kubernik interviews with D.A. Pennebaker, Albert Maysles, Murray Lerner, Morgan Neville, Henry Diltz, Graham Nash, Chris Hillman, Roger McGuinn, Mary Wilson, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, Andrew Loog Oldham, John Ridley, Curtis Hanson, Dick Clark, Travis Pike, Allan Arkush, David Leaf, Ray Manzarek, Robby Krieger and John Densmore.

During 2006 Kubernik spoke at The Library of Congress special hearings that were held in Hollywood on archiving practices and audiotape preservation.

Harvey served as Consulting Producer on the 2010 singer-songwriter documentary, Troubadours directed by Morgan Neville.

In 2020 Harvey served as Consultant on Laurel Canyon: A Place In Time documentary directed by Alison Ellwood which debuted om May 2020 on the EPIX/MGM television channel

Kubernik has penned a back cover book jacket endorsement for author Michael Posner’s book on Leonard Cohen that Simon & Schuster, Canada, will be publishing this fall 2020, Leonard Cohen, Untold Stories: The Early Years.

Harvey has lectured and conducted courses on the music business and film at UCLA and the University of Southern California).