Celebrates 50th Anniversary with new CD Collection and Criterion Collection Expanded Edition DVD of Monterey Pop;

Jimi Hendrix’s Birthday November 27;

and The Passing of Otis Redding on December 10, 1967

By Harvey Kubernik c 20017

Record producer, and Ode Records label owner Lou Adler, and songwriter John Phillips of the Mamas and the Papas produced The Monterey International Pop Festival, June 16-17-18, 1967, held in Monterey, California.

Thirty-two acts from the U.S. and England representing contemporary pop, rock, soul, psychedelia, folk, blues, and world beat were booked.

Stage performers and recording artists who appeared were The Association, Johnny Rivers, Simon & Garfinkel, the Blues Project, Buffalo Springfield, Big Brother and the Holding Company with Janis Joplin, Jefferson Airplane, Laura Nyro, Ravi Shankar, Grateful Dead, Mike Bloomfield’s Electric Flag, Moby Grape, Lou Rawls, Booker T. and the MG’s with the Bar-Kays, the Who, Eric Burdon and the Animals, Paul Butterfield Blues Band, Beverly, the Group With No Name, the Byrds, Otis Redding, Al Kooper, Canned Heat, Country Joe and the Fish, Quicksilver Messenger Service, the Jimi Hendrix Experience, the Mamas and The Papas, Hugh Masekela, Steve Miller Band, and Scott McKenzie.

The ramifications and influence of the sonic world of Monterey extended far beyond the actual gathering. The event altered world culture and your record and video collection.

The ongoing musical influence of Monterey on subsequent outdoor rock music gatherings is being acknowledged again with a myriad of fall and winter 2017 50 year anniversary products.

Out now is a brand new CD compilation produced by Lou Adler released from the Monterey International Pop Foundation which houses some never heard and rare audio performances. The informative liner notes were penned by influential UK-based music journalist and author Keith Altham who was in attendance at Monterey in ’67 covering the action for New Musical Express.

On this disc for the first time we discover Laura Nyro’s “Poverty Train,” the Electric Flag’s “Wine,” the Grateful Dead’s ‘Cold Rain and Snow,” the Butterfield Blues Band’s “Driftin’ Blues,” a Neil Youngless Buffalo Springfield’s “For What It’s Worth,” and Simon & Garfunkel’s “The Sounds of Silence, welcome additions to previously available tracks from Jimi Hendrix, Otis Redding, Jefferson Airplane, the Who and Hugh Masekela.

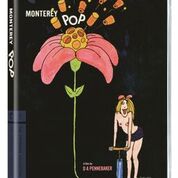

In June 1969 the documentary Monterey Pop by filmmaker D.A. Pennebaker was released and premiered at the Fine Arts Theater in Beverly Hills, California.

I went to the first screening.

In 2002 the Criterion Collection released documentarian Pennebaker’s The Complete Monterey Pop Festival DVD collection, expanded from his original Monterey Pop move first issued. The 2002 item incorporated two hours of never seen performances. The 16-bit 4K digital restoration was supervised by Pennebaker, with uncompressed stereo soundtracks.

Criterion in December 2017 has just issued an expanded edition of Monterey Pop to mark the 50th anniversary of this occasion.

Now implemented are outtake footage of “Viola Lee Blues” from the Grateful Dead, the long anticipated appearance from Moby Grape doing “Hey Grandma,” and fragments of the Steve Miller Blues Band of “Mercury Blues” and “Super Shuffle.”

Producer Kim Hendrickson also conducted a new interview with Adler and Pennebaker looking back over the last 50 years. Another bonus inclusion is a 20 minute short film by Ricky Leacock, Chiefs, that was programmed with Monterey Pop during the first 1969 theatrical run.

In 2012 my brother Kenneth and I wrote a book, A Perfect Haze The Illustrated History of the Monterey International Pop Festival, published by Santa Monica Press.

Amazon.com: A Perfect Haze: The Illustrated History of the Monterey …

https://www.amazon.com/Perfect-Haze-Illustrated-Monterey…/dp/1595800603

Over the last 40 years I conducted over 100 interviews with 1967 Monterey participants, including some new voices in 2017, and transcribed every one of them.

Interview excerpts that will appear below are culled from my research and multi-voice oral history narratives.

D.A. Pennebaker: Bob Rafelson, director of The Monkees TV show called me up and he said ‘would you like to do a film of a concert in California?’ And I thought about it and I had just seen Bruce Brown’s Endless Summer, which is not about surfing at all, but all about California. Every kid out of high school the one thing they wanted to do was get to California, and Endless Summer didn’t hurt.

“I saw Rafelson once, maybe, but he was never involved. It was always Lou Adler and John Phillips that I dealt with. And we flew up with Cass (Elliot) to see the place and I looked at it and it was this tiny place. I had no idea what was going to happen there. I had never seen a music festival at all. Not even Newport, so I didn’t know what to expect.

“It had a really nice feeling to it and I loved Monterey and it’s a lovely place. And I sort of thought, ‘well these guys John and Lou know what they are doing.’

“John was a total genius. He was part Indian and had a mystical view on everything he did. And he hadn’t been playing music for long. The Journeymen a couple of years before The Mamas and Papas. Everything he was doing was like he’d been touched and as long as the spell was there it just flowed out of him. I loved John. He was marvelous.

“Lou knew what he was doing and I knew he was a real good sound mixer ‘cause I had listened to some of the stuff he had done but I knew they were hatching a real interesting game. Which was from the beginning get rid of the money.

“That was the big thing. Get rid of the money. And I could see that was gonna make it work. It was a very Zen thing.

“In the Monterey Pop original movie interviews didn’t interest me and I had access to do it. I didn’t want to take the time. I wanted everybody to concentrate on music. Well remember: the guys I had filming for me there, except for Ricky (Leacock), he was the only other camera, they were all beginners. And I wanted them as I put them in pivotal positions ‘cause they could be with the music. They served the music and that was the thing. And I didn’t want them to think about anything except getting film to match that music.

“I knew when I saw Ravi Shankar we would have to end with that. I remember sitting down at Max’s Kansas City and I wrote out a little thing on the back of a menu of what I thought the order of the music would be and you know it was very close to what ended up being. The only thing I pulled out were Butter (Butterfield) and the Electric Flag for very peculiar reasons. But the fact is that I almost knew going in without even thinking about it that it had to build from Canned Heat to Simon and Garfunkel to whatever it was, it had to be a history of popular music in some weird way that I didn’t ever have to explain to anybody ‘cause I had John’s music as a narration for the whole film so that just covered me.

“Otis Redding was stunning. It’s a great film, almost a perfect film. He had a pretty good band. I was editing, or re-editing the section of his for Monterey Pop in late ’67 and changed the film a little bit when he went into the lake [on December 10, 1967 in Monona, Wisconsin].

“I remember that’s when I got in to all that stuff of doing things with the lights and I know at the time I felt, ‘Gee. What am I doing? This is crazy.’ But I left it that way because I felt so bad that he kind of died on us and that made me sad. So it was the only thing I could do to mark that was to edit that way. In editing Monterey Pop I had my first Steenbeck.”

Lou Adler: John and I hired D.A. Pennebaker who had done Bob Dylan’s Dont Look Back. We shot it initially as a TV show, because ABC-TV had given us the money up front. It was originally commissioned as the very first ABC Movie of the Week.

“After looking at the footage, I remember thinking; it’s too much for television. When we met with Tom Moore, the President of ABC-TV, we didn’t show him The Association, we showed him Hendrix. It didn’t take him long to say ‘Take it back. Not on my network.’ This turned out to be a blessing. We were able to keep the money that was paid so far and Monterey Pop became a film.

“The brilliance of Pennebaker, with his 9 cameramen, is that he was able to capture what happened, not make it better…not make it worse; really show what happened, the raw emotion. If it’s Hendrix or the Who, he goes to the right person in the audience; you get the feeling the audience was feeling. To me, what I get when I watch the film are my memories of what really happened those three days.”

D.A. Pennebaker: When I showed Hendrix to ABC they said ‘no thanks.’ And they owned the film and all they had to do was sign some shit and they would have taken it free, but they let it go because they knew he couldn’t play on their network.

“When I first heard Hendrix at the 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival I thought he was chewing gum on stage but it was actually his flat pick. I thought, “This is not blues. This is bull shit.” But, you know, about the third song I saw that I didn’t understand and I began to dig it. And that was an amazing moment. And that’s why we shot every song that he did. Because it kept growing in a way that we hadn’t expected.

“But at the same time what was so marvelous and just sitting on the stage with our legs hanging over with Janis, and saying ‘What do you think will happen to you next?’ And trying to see ahead into the future. And this woman has got such a future if she doesn’t blow it that I just want to be part of it.”

“I think of these films like Monterey Pop much more as if they were plays on a stage. And every play has to build to some sort of climax. Something it was all worth sitting there for. And that’s how you decide what comes next. And there was no dialogue.

“You put your mind into that and then it sits there and you don’t have to think anymore. What you want to do is get so that when you’re shooting you don’t have to think. You don’t have to think about, ‘Should I be closer?’ As soon as you think those things, the film disappears. You want your feet to take you where you should be. You want the camera to film what you want to film. You don’t want anything to happen so you won’t have to think about it. And then it can happen in some part of your brain that’s non word-oriented, or something, I don’t know. But I get in that camera and I don’t want to come out.”

The roots planted in the June 1967 soil of the Monterey festival can be traced back to Jim Dickson and his community activist commitment which originally grew out of the February 11, 1967 CAFF (California Action for Fact and Freedom) benefit concert at the Valley Music Center in Woodland Hills, California.

The Byrds, Peter, Paul & Mary, Buffalo Springfield, the Doors and Hugh Masekela headlined the CAFF event. Dickson, Alan Pariser (who was heir to Sweetheart Paper Cups) and Ben Shapiro [agent] produced the show that helped defray the legal expenses of teenagers arrested by The Los Angeles Police Department ‘Riot Squad’ regarding the 10:00 PM curfew incidents on under 18-years olds around the Pandora’s Box nightclub on Sunset Blvd.

“It wasn’t a riot at all. Of course not,” suggested Dickson to me in 2012, who co-managed the Byrds at the time. “They instigated some of those things. There were a lot of people who weren’t Strip regulars. It became the place to be which was all right. And very few shop owners complained to me.

“I was more than busy and involved in the management of the Byrds and the CAFF concert,” Dickson explained. “The committee included Lance Revelow and deejay B. Mitchel Reed. That took a lot of time and it meant going in the street and being in touch with The Board of Supervisors and The Coliseum Committee who made the decisions on leasing out arenas in L.A. County. Ernest Debbs was the supervisor for the district that included Sunset Strip.

“When he saw my proposal and saw we had the support of radio station KRLA, and a KFWB DJ on our Board, BMR, who agreed to promote it, and they did. He said, ‘my daughter listens to KRLA more than she listens to me.’

“One guy tried to stop me. In real life he was a Pontiac dealer. ‘This guy is dangerous.’ Ernest Debbs knowing that I knew a lot of the people that he knew in the area said, ‘People in the United States have the right to petition their government and we should listen.’

“I created the Valley Music Center CAFF event and turned it over to Alan Pariser to run it once it was set and all the bands secured. After the show Hugh Masekela said to Alan, ‘We gotta do another one.’ Alan got it rolling and took it to Benny Shapiro.

“When Hugh first said to Alan to do another show, the first idea was to do it in Tijuana. That’s when I drew the line. I entered the conversation. ‘No. No. No. Do you really want to get a bunch of young kids down in Tijuana? The trouble is enormous.’ No one argued with me when I told my story about Tijuana and how Monterey would be much better. Beautiful with green lawns. Benny had already done The Monterey Folk Festival up there.

“‘What you should do is talk to Ben Shapiro because he put on the Monterey Folk Festival and you should do it Monterey. And he’ll know whom you’ll have to talk with to do that.’

“The permits were then put in Alan’s name. All I did was steer Alan in that direction and go see Benny. ‘Cause he knew the machinery to get Monterey. And then Lou Adler and John Phillips took it over.”

Shapiro was looking for a pop group to headline, and on April 4th, he had dinner with John and Michelle Phillips of the Mamas and the Papas.

Lou Adler: Not long after that Alan Parisier and Benny Shapiro approached John, I and Michelle for the Mamas and the Papas to headline a one-day one-night concert at Monterey. We said the Mamas and the Papas would only appear if the festival was for a yet to be named charity and that all of the acts would appear for no fees but full first-class expenses.

“Simon & Garfunkel completely supported the idea. I think Shapiro and Parisier understood the drawing power of those two acts. Benny wanted it to be a commercial event, so in order to eliminate the conflict he let us buy him out for $50,000. Johnny Rivers, Paul Simon, Terry Melcher, John, and I put up $10,000 each.”

Michelle Phillips: When there was ten thousand dollars offered initially for us to headline a show in Monterey, we didn’t take the money, there wasn’t any money left for any support acts if we took this offer, we chose to go non-profit.

“And, I’ll tell you something, I don’t think Monterey Festival could happen if the money was on the table. I don’t think that concert could have ever happened if the performers were paid. I mean, where would all the money have come from to get them there and to pay them? I think that logistically it would not have worked. That’s when John and Lou came up with the idea of doing a charitable event. They had to scramble to think about what the charity was going to be. They were making up all sorts of things like music schools in Harlem and Watts.”

Lou Adler: I moved into Bel-Air in 1965, then John and Michelle up on Bel-Air Road. Brian and Marilyn Wilson then moved into the immediate area. The neighborhood accepts me, even though the look is completely different from what is going on in Bel-Air. They sorta accept John and Michelle. Brian comes in and paints his house purple…and at that point we’re all suspect.”

In spring 1967, Lou Adler and his lawyer, Abe Somer, did the paperwork for non-profit status for Monterey and now both on the Board of Directors for the multiple day festival.

On April 9, 1967 the Beatles’ Paul McCartney flew in from Denver, Colorado, to Los Angeles in a Lear Jet owned by Frank Sinatra. On arrival Paul visits the Bel-Air mansion of John and Michelle Phillips of the Mamas and Papas, a pad above Sunset Blvd. formerly owned by actress Jeanette MacDonald.

The Phillips’ house was considered a little funky for the posh and security patrolled “old money” Bel-Air section of Southern California. Tonight the tunesmiths and music lovers were mostly huddled in the Pub Room.

The Monterey Board of Governors listed Brian Wilson, Roger McGuinn, Donovan, , Andrew Loog Oldham, Terry Melcher, Paul Simon, Alan Pariser, Smokey Robinson, Adler, Phillips, and Johnny Rivers. Wally Heider recorded the festival. In 1964 Heider engineered Rivers’ Live At The Whisky A Go Go that Adler produced.

While in Los Angeles that night McCartney was quickly invited to join the advisory Board of Directors, which is planning the Monterey International Pop Festival. Adler and Phillips had just formally taken over the production of the event, now scheduled in just two months.

Lou Adler: The motivation came that night at John and Michelle’s with Cass, Paul McCartney, myself and a couple of others; our conversation went to rock ‘n’ roll as an art form, like Jazz. John and I were both aware of the Jazz at the Philharmonic recordings. Someone said, ‘They aren’t taking rock ‘n’ roll musicians seriously.’ Rock ‘n’ roll was always viewed as a fad that would be over by the summer…but now it was more than just music, it was a lifestyle.

“McCartney’s first recommendation (simultaneously along with Andrew Loog Oldham that same afternoon) was to book the Jimi Hendrix Experience since they were tearing up England at the time.

“We looked at Paul beyond an act. Beyond somebody that was singing on stage. As a composer. He was somebody not writing just hits, but great songs. Like ‘Michelle.’ There were two meetings between the Mamas and Papas and Paul McCartney. The first one was in London in 1966. McCartney played piano all night. And he played on the strings as opposed to the keys.”

Chris Hillman: Monterey really was presented as an idea to us [The Byrds], not through a booking agent, but initially by Alan Parisier, and then later Lou Adler and John Phillips. Alan came up with this idea, then Benny Shapiro, and Lou took it over with John Phillips.

“I knew initially, at age 21, or 22, asked ‘Why are we doing this for free? Who gets the money?’ ‘Well, it’s going to charity.’ I’m glad to know now where it ended up and now I feel better. It never bothered me. (laughs). I appreciate it. So, we took the booking.”

Lou Adler: Derek Taylor and Alan Parisier, part of the original Shapiro team stayed on; Derek as Public Relations Director, who set the bar as how rock ‘n’ roll PR should be handled. Alan Parisier stayed on in a production capacity; his contribution is historically underrated. The idea to stage a festival was probably his idea in the first place. Tom Wilkes had been hired as the art director and Guy Webster was the official photographer.

“We were now The Monterey International Pop Festival. We were based at the Renaissance Club at 8424 Sunset Blvd. …The Sunset Strip, across from Ciros. The Renaissance was formally a jazz club, and I remember seeing Miles Davis there.

“We now had three days in June, the 16th, 17th & 18th booked at The Monterey Fairgrounds, and three acts committed. The Mamas and the Papas, Simon & Garfunkel, and Ravi Shankar who had signed a contract with Benny Shapiro, who would be the only act to be paid, as we chose to honor his contract.

“Paul Simon took a position from the beginning. He is on the Board of Directors and he had an invested interest in the festival because he put up ten thousand dollars. He also had an interest in what we were trying to do. He understood, he came aboard right away. We knew him for a while.

“We went up there two weeks before we moved into the Monterey Fairgrounds. At this point, it sounds crazy, ‘you can’t do the festival, you can’t get the acts, or work out the transportation,’ but that’s because there’s rules and regulations now. There were no rules then. The acts that we found had conflicting schedules like Dionne Warwick was already set to appear at San Francisco hotel.

“There weren’t a lot of tours. We’re still talking 1967. Not a lot of acts are working all the time. The San Francisco acts are playing around San Francisco. The big acts couldn’t get visas to get in. The Motown acts were working, the blues acts were working, but the acts that we went after, they had time even though we had a short window. That’s how bookings went. ‘What are you doing in the next two weeks? I’ve got a job for you in Hawaii.’ The timing and everything was in order.

“Whatever we wanted seemed to be available to us. FM radio became an alley. The album tracks replaced the single.

“Everyone jumped on very quickly. We tried for the Impressions. We got some no’s, from some of the Motown acts and Chuck Berry passed. I had Chuck on (earlier) tours and he’d stand right before the curtain. His hand would go out, you’d pay him, and he’d go on stage. That’s because he got burned so many times he wasn’t about to do it. But to his credit, Otis Redding’s manager, Phil Walden, understood it immediately.”

Rodney Bingenheimer: Derek Taylor fixed everybody up and made sure the right people were taken care of. Before the festival I was handing out bumper stickers in Hollywood and Sunset Blvd. about it.”

Andrew Solt: In 1967, I was on the Sunset Strip at least three nights a week. I saw the billboard on Sunset Strip for the Monterey International Pop Festival. My God! What is this thing and where do I get tickets? So I bought tickets. I had no idea, walking by a room on Sunset Blvd. that it was the Monterey production office. I had been to San Francisco before and to some Golden Gate Park concerts.”

Johnny Rivers: Jimmy Webb was in my band for Monterey on keyboard and we worked on my set and the charts before we went up there. Hal Blaine, Joe Osborn and Larry Knechtel were not available for rehearsal ‘cause they were booked up. But what we did do was stay at the Highlands Inn up there, just south of Carmel, and got one of those banquet rooms the day before, and it was the first time we ever played that stuff.

“Driving north on Highway 101 I had never seen so many VW buses pained with paisley and flowers, cars, trucks, and lots of out of state license plates. People were from everywhere. The vibe was very mellow and kind of the theme of the whole thing. It was a gathering of tribes and hadn’t really gotten to the wild hippie stage yet. The ‘Summer of Love’ was the summer that came after that. It wasn’t going to be frantic, out of control, but everyone digging on the music. Because there was such a variety of music.”

Henry Diltz: I did not know Simon & Garfunkel but of course we knew every note of every song. To see their two heads, right next to each other in the middle, at the microphone, right after seeing groups and bands. Just the two of them. A hush fell over the whole crowd. Paul Simon orchestrated the songs. So simple but so full. And so perfect with the blending of the voices. Garfunkel’s voice. It was the interplay of the harmonies that made it so beautiful. Garfunkel was more the voice, and Simon would do the harmony part below it in some cases. I always think of him as kinda putting the cement in there, but Garfunkel was really the voice.”

Lou Adler: Their live set. The purity of the vocals. I think there might have been one or two other acts you might have listened to just vocally as opposed to the whole. They were the only act you listened to those vocals and you tuned in just on the vocals. Paul played acoustic very well. Interesting, Al Kooper’s quote about how many guitar players were at Monterey, and amongst all the rock guitar players he says Paul Simon. The vocals are so beautiful when you listen to Artie, and the setting was just right. I mean, the first night, it was really dark, and the purity is what you get.”

Andrew Loog Oldham: I do not think I suggested Eric Burdon, even though I loved Johnny Weider. It was nothing to do with Eric and the New Animals covering ‘Paint

It, Black,’either. It was just obvious. I think I was too much of a snob to suggest the Animals, and anyway, for a while, with Mickie Most they’d had more hits than us. It turned out to be Eric’s coming to America and his Tom Wilson period that was so wonderfully productive. And from that did we not get War?”

Jerry Wexler: Otis’ show at Monterey astonished me because he nailed that audience of hippies and weed heads in a way that was astonishing to me because that was not his core audience. He nailed those hippies that was unreal. A very loud fantastic rock band went on before them, I think Jefferson Airplane, you know with the 20 foot Marshall amps and all of this, so it was roaring.

“Now Booker T. and the MG’s open their show with their little Sears Roebuck amps. And you know what, it quieted down. The way you control a noisy crowd is if you are good you play soft. You don’t try and out volume them. So they had it set up, and were so good, they commanded so much attention, and when Otis came on the crowd was ready.”

Steve Cropper: We didn’t have to do sound check or rehearsal at Monterey. Just plug up and go out there and play. Our clothing was different than the flower children. And that was the start of ‘be yourself and do your own thing.’ One of the things that I recall is a very big compliment coming from Phil Walden, ‘cause Phil was about Phil, and Phil was also about Otis Redding. And they told Phil at Monterey, and you know we went on really late that night, and there had been some delays with the equipment because it was drizzling, and stuff. Someone running the festival came backstage back to Phil and said, ‘you know we’re really only going to have time for Otis Redding. Let’s just bring Otis straight on.’ And Phil said, ‘Balony.’ You’re not touchin’ this show. These guys are gonna go out and do the same thing they always do.’

“Which meant we brought out Booker T. and the MG’s, we did one or two songs, and brought out Wayne (Jackson) and them, and did ‘Philly Dog’ and maybe ‘Last Night,’ and then we brought out Otis. And, that’s the way we did it, and Phil stuck to his guns.

“The other thing that happened was that about three or four songs into the set, the (Musicians) Union there came back and said ‘we’re gonna have to shut this show down because we’re over curfew.’ And, Phil went over to them, ‘You ain’t touchin’ this. Them boys are gonna finish this show!’ So we didn’t know what was going on. We heard about this later.

“At Monterey, that audience sat out through the rain to see us, or wait to see Otis Redding, ands that’s the first time I ever experienced that. And they were more curious than anything else. Otis had found his audience, and Monterey helped him cross over to a wider white pop market. They already knew how big he was in Europe and Europe.”

Andrew Loog Oldham: When Otis came on stage you forgot about the logistics. We knew we were taking one small step forward for mankind. Phil Walden, his manager, was in heaven, he knew he’d just graduated from buses to planes. Phil Walden was one of the greatest managers of his time. His enthusiasm, his pure chicanery, his belief, his service to Otis was an example to the game.”

Paul Body: He brought Memphis to Monterey. He turned the festival grounds into a sweaty juke joint on a foggy night. I was standing up on someone’s car that was outside and we danced on the roof. Otis looked like a king dressed in an electric green Soul suit. He came on like a hurricane singing Sam Cooke’s ‘Shake’ at breakneck speed.

“It was a real electric moment. He looked like a damn fullback up there. He was as magnificent as a mountain. It looked like nothing could stop him. He could rock but when it came to that slow burn Southern style, no one was better. He was giving the love crowd a lesson in slow dancing. He ended with ‘Try A Little Tenderness’ turning it inside out and making it scream for mercy. He slowed it down to a simmer, started off some mournful horns, Booker T’s organ and his voice. Al Jackson came in with light rimshots that sounded like raindrops from heaven in the foggy night. Then Cropper came in with some tasty rhythm chops, then Al started beating out the groove, pushing it and they took it home. I had never seen anything like it.”

Keith Altham: Otis Redding at Monterey. If I am absolutely honest, Otis Redding was not my particular bag of music and why did he really fit in to that whole kind of revolutionary new style of music. We’re talking soul. The one thing he had was the most staggeringly beautiful voice. He was not the greatest mover on stage. Although he projected. I didn’t realize how big he was. Such a massive man! And, but could he sing! Just a wonderful voice.

“I’m so glad I actually heard him live and feel priviledged I was there on that particular situation. There was so much that was new that came off that stage. From Buffalo Springfield to Janis Joplin.”

Roger McGuinn: I remember watching Otis Redding and he really blew my mind. I had never seen anything like him before. I remember I was backstage listening to Otis and Paul Simon and I were talking. I said, ‘Man, this guy is scary!’ And Paul replied, ‘He’s not scary. He’s great!’ ‘That was what I meant, Paul.’

Al Kooper: I watched Otis Redding disarm the audience. He was fantastic. The audience sort of didn’t know him and he hadn’t played in front of white people before. It was great. ‘This is the love crowd.’ Shit like that. They gave him a lot of love. And, he had one of the greatest bands in the history of rock ‘n’ roll behind him. I’d seen Al Jackson before. He was like the Charlie Watts of black music.”

Paul Kantner: As Jefferson Airplane we had played earlier at the Monterey Jazz Festival. We were invited because we were the new hip band. They were stretching out that year which was the nature of the times. Thank God what a great nature that was. When we earlier played the Monterey Jazz Festival, (music critic) Leonard Feather wrote ‘we sounded like a mule kicking down a barnyard fence.’ By the time we did Monterey Pop festival we had a record deal with RCA and an album out that we recorded in Hollywood.

“As far as San Francisco being suspect of L.A. and Hollywood people, we always tried to get above that if possible as a general rule. People didn’t like the Doors. ‘Cause they were from L.A. (laughs). So there’s an immediate antipathy and I liked the Doors a lot and toured with them. I created that lack of that antipathy in myself. I rejected the suspicions of L.A. as a general rule. I throughly enjoyed L.A. and New York. I could make myself comfortable in either one of those cities. I liked San Francisco a lot.

“I wasn’t aware of the record business, or music scouts at Monterey, either. We just came to have a good weekend and play, basically. We had the light show and took it around with us when we started touring. It was one of those things that appeared. Even without the light show we still had really good music, singers and songs. The light show was just an added enhancement where we could get it involved and traveled with us after a while. Expensive. I enjoyed just the overall whole thing of Monterey Pop.”

Marty Balin: For me a highlight of the Monterey International Pop Festival was Otis. I had been around and he knew who I was. We went on before he went on. And nobody got the crowd moving but when the Airplane came on we got the crowd moving. We got them excited and got ‘em up and dancing. And I walked off and Otis Redding was standing there and he said, ‘Hey man. It’s a pleasure to be on the same stage with you.’ For me, that was it, baby. Right there. He staggered the crowd.”

Michelle Phillips: I only saw the only last three minutes of Otis’ set…I wanted to kill Laura Nyro (laughs). After she came off the stage I could see that she was really, really upset and in tears. I just grabbed her by the hand, I put her in one of the limousines in the back, and said to the driver ‘let’s go for a ride’ so I could calm her down. And I think we were smoking a joint and I was telling her that ‘she was great,’ and she said, ‘No, they hated me and I looked like an idiot up there.’ I was just trying to do the sisterly thing. I was chilling her out and came back to catch the tail end of Otis-the one act I was just dying to see.”

Chris Hillman: I thought Otis Redding was unbelievable.

“He played the Whisky A Go Go and Michael Clarke and I went, sat down with him, and he bought us a drink. Sweet man.

“Mike and I on the early Byrds tours, we used to take battery-operated tape recorders and loved listening to R&B and blues.

“One night at Ciro’s Mike played drums for Major Lance when his drummer didn’t show. And his hair is processed, and he turned around, ‘Hey drumma. Thanks man. Good job. ‘Six bucks!

“I remember watching Otis…I can’t compare it to anyone. Even my brief viewing of the Beatles at the Hollywood Bowl. They were so good but they had to keep stopping the show. Screams, but they were so tight. Otis Redding…It was like…I remember watching Otis Redding and I had seen Sam & Dave at the Whisky.

“And that was just a whole other level of professionalism, Harvey. We took everything so laizafaire out here. We weren’t entertainers. You follow? We weren’t supposed to be a Las Vegas act. But that would have taken the whole mystery out of the Byrds or the Springfield, or any of those bands. But those guys were real professionals. They moved, they danced, and went into songs.

“One of my favorite albums of that era, James Brown Live at the Apollo. That record is so good you’re almost there in the audience listening to that record. And, that’s how tight the Otis Redding band was at Monterey.”

Chris Darrow: We [The Kaleidoscope] played the Monterey Pop Festival, but not on the stage. Too bad! Somehow we set up outside the venue to perform for all the Hell’s Angels and others who couldn’t get in the gate. I was at the festival. I remember Brian Jones walking around.

“Months later I was asked to join the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. We shared the same nanager as the Hour Glass, a band from Georgia who later became the Allman Brothers. We all hung out a lot and, over a period of time, I became friends with most of the people in the bands, especially Duane Allman. He and Ralph and Holly Barr were very tight and when I was in L.A. (I lived in Claremont), I spent a lot of time at their house and got to know Duane. Both he and Ralph were phenomenal guitar players and there was mutual respect all around.

“One night on December 10th of 1967 the Dirt Band had a radio interview at a club called the Magic Mushroom in Studio City hosted by Phil Procter and Peter Bergman of the Firesign Theater for their Radio Free Oz program on KRLA. I had a blue, 1954 Ford two-door and had some room in the car for some riders. Jeff Hanna was in my front seat and Duane wanted to come along for the ride. We all had heard earlier in the day that Otis Redding had been killed in a plane crash somewhere in the south. I will never forget Duane sobbing in the back seat of my car over the death of his ‘main man.’ I remember back to the time when I cried uncontrollably when I found out about the death of Buddy Holly and Ritchie Valens. When our heroes go what else is there to do?”

Keith Altham: Monterey to Jimi Hendrix was like coming home. He knew that he had to live up to all the plaudits that he had from his peer group in England, you know. The Prince of the rock guitar. Who was Eric Clapton, who was the man at that time. And Jimi was very anxious to meet him.

“Nothing like coming out to Monterey and playing to a large crowd. Probably the largest he’d ever played too. And seeing that kind of ground swell of interest in progressive rock music gave him hope for the future and an indication perhaps of the direction he might be able to take the music.

“I think although there wasn’t a road to Damascus at Monterey, I think he felt that it was yet another step up the ladder. He knew that was a foot in the door. I don’t think it broke Jimi in America. I think it put a foot in the door and brought him to the attention of the mass media in America, and indeed to television and radio exposure which he had not had yet. One guy in the press pit with me said after he finished, ‘what the hell was that?’”

Chris Hillman: Jimi Hendrix…His playing. He was so out of left field that’s what got everybody. Not the burning of the guitar. That part was minimum. Here he was getting this tone on a guitar no one has heard before. My reaction at first was that’s a lot of noise. Noel Redding was really loud and the drummer (Mitch Mitchell) was playing nine million fills. But then that guitar tone comes in. And let me be honest with you: I didn’t appreciate Jimi Hendrix until 15 years afterwards. And I started to hear the blues stuff later on he did after all the show…He was such a good player.

“Earlier, we got to know him. Mike Clarke and I went to Ciro’s and Jimi (James Marshall) was playing guitar for Little Richard. Roger went as well. He was a sideman on the end of the stage playing left handed. The best part of the night was we had these stupid suits that Jim Dickson bought us and we left them in the Ciro’s dressing room and Little Richard’s band stole them.

“And we went, ‘Thank God,’ because they were like these velvet collar Edwardian Beatles suits, but there was Hendrix. You could not help but look at him and hear the sounds he was making on the guitar. And playing lead in an R&B rock ‘n’ roll band where you not the showcase. It’s the horn section carrying it. Very few guitar solos, mostly rhythm and stuff, but we said, ‘Who is that?’ Because the guy was so good. And then a year and a half later there he was at Monterey.”

Jerry Wexler: Jimi Hendrix story, before the psychedelic phase, was playing with King Curtis and around New York. At Monterey I’m in the wings when Jimi walked up to me just before he was going on stage and now he is in full psychedelia regalia in feathers and a costume. And, he looks at me, and almost apologetically, runs his hands all over himself and days, ‘Hey man, this is just show business.’ Because of his outfit.”

Johnny Rivers: When Jimi Hendrix came out I was standing in the wings next to Lou Adler, and the fire marshall was there, and that whole entire stage is made out of wood. The walls, ceiling, floor, wood. It’s still exactly the same.

“When Jimi pulled out that lighter fluid, threw his guitar down, pulled out these matches, the fire marshall started to run out on stage, and Lou actually grabbed him by the arm, and told him ‘It’s OK, it’s just part of his act.’ Lou calmed him, because the guy was just gonna grab Jimi on stage, And, the guy kinda stepped back, for a split second, and thought Jimi was gonna fake lighting the guitar, but then when it actually went up in flames, he flipped out! He went running looking for a fire extinguisher. Jimi kind of sat over it like he was having sex with the guitar, and a roadie came out with a big towel and threw it over the guitar and dosed the guitar out.”

Robert Marchese He started playing, and I didn’t know there was anybody doing anything new or different. This is it and what I’ve been waiting to hear for a long time. The way it should be. He walked off, I shook his hand, and I said, ‘You’re the most psychedelic Negro I ever heard.’ (Laughs). That was my comment. And Jimi replied, ‘That’s right. I’m gonna make a lot of money.’ ‘Yes you are.’

Mickey Dolenz: I do remember after the Hendrix show that night, I ended up somehow as this sort of mascot to Jimi and God knows who else. I had acquired instruments, amps, guitars and a generator for electricity, and long after the show was over, and the event had essentially ended, everybody was so pumped up it was tough to go away. And there wasn’t anybody who was forcing anyone out of the area. It was this ongoing kind of buzz that was happening, and people would gather in little groups and corners and tents, and keep going.

“There were jam sessions. I fell in with Jimi. And I sat there with a lot of other people, I wasn’t playing, there was no drum set, and people were playing on their knees. It was like ‘Kumbiah’ in a psychedelic way. We all sat there for hours until the morning. Somehow, I got the idea, and everyone was hungry and thirsty, maybe it was the Boy Scout in me, but I wanted to contribute to the vibe, and I went out of the tent and somehow finding a case of oranges. I lugged this entire case of oranges back to the camp, the tent, and started giving out oranges, like I was ‘Little Johnny Orange Seed.’ I think I might have also heard at the time that oranges, or orange juice were helpful after an indulgence of chemicals…(laughs). I later crashed out at the Carmel Inn.”

Al Kooper: Michael Bloomfield was already ahead of me. He had put the Electric Flag together. Our careers were amazing parallel, in that we met on ‘Like A Rolling Stone,’ he was in a blues band, I was in a blues band, we both quit the blues bands we were in to start horn bands. We both got kicked out of the horn bands that we started. And, that’s when we did Super Session, because if anybody is supposed to be together it is him and me. But let’s do it on a flexible basis. Let’s not get married. Let’s just screw on record.

“At Monterey I thought the Mike Bloomfield Thing was very exciting. I was very happy for him. I thought Buddy Miles was amazing then. And I was in the wings when they came off. Buddy Miles was crying. I saw Butterfield’s set and I thought it was great and he was using horns for the first time in front of a lot of people.”

Barry Goldberg: Our Electric Flag rehearsals were a couple of gigs at the Fillmore where we opened up for Cream. Nick Gravenites was really tight with the Big Brother guys. He loved Janis. I talked to Brian Jones for about a half an hour at Monterey. He knew Paul Butterfield, and I think had seen Michael when he was with Butterfield in 1965, or ’66 when Butterfield played in London.

“At Monterey, after our set, it was a relief it went well, and that we were received so well because nobody knew what was gonna happen. That was a big deal. Because we could have blown it. But we came through. I saw Jimi, and he called over to me, ‘Hey Piano Man,’ that’s what he called me, ‘What’s happening?’ ‘You are!’ I remember that like it was yesterday.

“Shortly afterwards I wrote a tribute song with Michael Bloomfield about Hendrix, ‘Jimi the Fox,’ and we did it on our album Two Jews Blues. Later, when Jimi and Buddy Miles did Band of Gypsys, Jimi told Buddy how much he really liked our song about him.”

Peter Lewis: For Moby Grape the Monterey International Pop Festival was the crossroads. Everybody was fascinated with psychedelic music at the time, the San Francisco bands were as the center of it. But playing for a bunch of kids that are high on LSD is not the same as being high on it yourself when you’re playing for them. I don’t know what the Mamas and Papas had in mind. But to me it seemed like like all the L.A. bands, they wanted to stay ahead of the curve on what was happening in the business.

“I’m not sure I thought about the night we played as a chance to prove anything. But our old manager did and had an argument with Lou Adler about it. Adler decided not to put us in the film. The band didn’t know about this until after the fact. When we did find out what our manager had done we fired him. But the real damage was undoable and in retaliation, instead of playing in a prime Saturday night slot, Adler had us open the show on Friday night. So instead of a slot on Saturday night with Otis Redding, we were booked in an early slot on Friday when people were first arriving. There was nobody in the place.

“As I recall we had a good set anyway and went by real fast. The vibe at Monterey just got better all weekend and by the time it was over I really felt like I was part of something bigger than the sum of its parts. This all had to get worked out. But to me it really seemed like when it was over, all the bands left with a sense of renewal. It was as if the days of trying to out play each other were over and in its place was a common cause.

“If I had to describe it, I would say it was seeing that a spirit of conflict lives in each of us.There is no war that can be won in the outside world against it. But we can defeat it in ourselves.

“I remember being backstage with Jimi Hendrix before he went on. It was great, he did what he did, all self- explanatory. The hippie black movement was not around until Jimi Hendrix. He showed up, the songs he sang, “Foxy Lady.” He wasn’t singing “Old Man River.” He did that and got everybody on that trip. He knew as long as they kept thinking about him on that level that he could turn into something like that. It reminded me more of voodoo. It was about music, and he could really play.

“There was a new frontier at Monterey, and a tremendous hope. It’s like some of the music you had the sense that the people who made it to that stage kinda knew something. Whatever they knew was like part of their music, whether they were expressing everything, literally or not. Only Bob Dylan was really doing that.

“Our debut album had just come out. We all went to a party thrown by Columbia Records head Goddard Lieberson. He had a turtleneck sweater and a little gold chain, with his hair combed down in front, and he didn’t have long hair. So he was trying to look cool. And, he had a party at his hotel, and I remember jamming with Paul Simon for a while. Tons of people. Janis was there because they wanted to sign her. Janis Joplin couldn’t get arrested before Monterey. Her trip was, one day everyone is kicking your ass, and then the next day everyone is kissing it. It does something to you.”

Keith Altham: Janis Joplin was the staggering thing I saw on the whole show to me. Because I had never heard a woman sing like that.

“I told her afterwards ‘you’re the best female rock singer I’ve ever heard in my life.’ She looked me up and down, smiled, and said, ‘You get out much, honey?’ (laughs). I thought it was funny. She was very friendly. I liked her.”

Henry Franklin: Hugh Masekela saw me play at Memory Lane in 1967 in L.A. when I was with Willie Bobo. Monterey was my first festival and Hugh added the guitar player, Bruce Langhorne. I got to see Jimi Hendrix, Otis Redding, and Janis Joplin.

“You got to remember, we were basically jazz artists, I was a young dedicated jazz artist. My father was a band leader in South Central Los Angeles, so it wasn’t my thing at the time, because I hardly knew who these people were. I knew Lou Rawls. Hendrix’s set was out there as far as I was concerned. I learned a lot about him later on. You know, at the time, I’m a young jazz guy who only listened to KBCA-FM.

“I met Otis. He was great, and destined for stardom. He had that fire. He was amazing. I saw a little bit of Janis, and she was nothing but energy. I

learned a lot about her later in life. The feeling of the whole place was that everyone loved everyone. I was amazed. The world was different then. Everyone was getting high. I smelled marijuana all over the place. It was no big deal.

“They loved us at Monterey. Big Black was a bad mama jamma. Big Black played ferocious. The jazz people weren’t treated as step-children for once. That was wonderful. That changed a lot of my thinking from then on. A great, great sound system.”

Chris Hillman: Hugh Masekala at Monterey was one of the highlights, and earlier recording with him was one of the highlights of my life, in that, and David was on that session, we were playing with all these South African musicians way ahead of Paul Simon and one of them was a piano player called Cecil. And he was the great inspiration for me to write ‘Have You Seen Her Face.’ There was something that connected with me and that was where I came out of my shell with that session. I came home and wrote ‘Time Between Us’ and wrote songs that entire week after that session.

“At Monterey we did Dylan’s ‘Chimes Of Freedom. I didn’t realize how beautiful that lyric was until years later. And Jim Dickson, and you gotta give ol’ Jim credit, he instilled in us the concept of depth and substance.

“He said, ‘Do you think you’re gonna be able to listen to this 20 years later?’ And, here we are yelping about ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’ when he brought it to us. ‘Chimes of Freedom’ and the version we did on that first album was the band. We all knew it. And ‘Chimes of Freedom’ is a killer. It’s just one of Dylan’s beautiful songs. And he was just peaking then.”

Roger McGuinn: And you can see out set on You Tube with David talking about the Kennedy assassination. ‘Renaissance Fair’ our opener that I wrote with David was the perfect song for the festival. We had just recorded it. It was another new song. We were doing new material, and not relaying on our hit records.

“I didn’t know David was going to sit in with Buffalo Springfield, and that wasn’t really a big deal. What was happening was that we were not happy with each other, like a marriage breaking up. He was really upset because we didn’t do his song ‘Triad.’ That was the big bone. He wanted to be the lead singer of the Byrds, you know, the head Byrd. That wasn’t happening. To his satisfaction we were sharing vocals equally. At Monterey I was trying to be a trooper, like Bobby Darin taught me, and try and soldier on and do it.”

Ravi Shankar: I arrive in Monterey and see butterflies and colors and flowers with peace and love. It was fantastic. I was impressed and I was meeting all these beautiful people. Fine. It was one day before my concert and I went to hear the whole thing. That to me was the real experience.

“One night, I really heard Otis Redding. He was fantastic. One of the best, I remember. Then, you know, came the hard rock. The Jefferson Airplane. The Grateful Dead. To me it was difficult in a very loud, hurtful in-my-ear way. And Janis Joplin. I had heard of her, but there was something so gutsy about her. Like some of those fantastic jazz ladies like Billie Holliday. That sort of feeling, so I was very impressed by her. Then, some others and what really disturbed me was the hard rock. The worst was to come.

“I had heard so much about Jimi Hendrix. Everyone was talking about him. When he started playing…I was amazed…the dexterity in his guitar playing. But after two, three items, he started his antics. Making love to the guitar, I felt that was quite enough. Then, all of a sudden he puts petrol on his guitar and burns it. That was the leaving point. Sac-religious. I knew it was a gimmick.

“Then, the Who followed, started kicking the drums and breaking their instruments. I was very hurt and ran away from there along with the others who play with me. My feelings were hurt deeply, as well as my respect for music and the instruments.

“The next day, in the afternoon, we set up a special section between 1:00-3:00 p.m. where there would be no one in front of me and after me. It was cloudy, cool, it had rained a little and that’s when I played and it was like magic. Jimi Hendrix was sitting there. (Jerry) Garcia was there. I remember a few names. All of them were there and you can see on the film what magic it had. I was so impressed and it is one of my memorable performances. I didn’t plan for this.

“I was grateful to God that I was sitting in the atmosphere without anyone disturbing me. It drizzled for a few minutes and then it stopped. So, it was was cloudy and there were flowers from Hawaii and you know, what atmosphere!

“After my set, it was crazy. I have never felt such a commotion of this sort. I was so pure, in spite of the fact that there were many people who were also strong. But it didn’t matter, because the whole atmosphere was so clean and beautiful and I could give my best. That’s all I can say.”

Mickey Dolenz: Ravi Shankar was the most moving, spiritual experience and it allowed you to get into the pulse and the rhythm and into the deepest meditation. If you opened your eyes and saw people with their eyes closed just listening and being and swaying. No one was smoking, no cell phones (laughs). It was two hours of uninterrupted meditation. In the afternoon. It probably had a great effect but first of all it was dark in the sense most people had their eyes closed…I’m not sure if it would have mattered if it was day or night. It was just being in the presence of those musicians [Ustad Alla Rakha and Kamala Chakravarty] and experiencing a form of music not yet really.

“The Beatles had sort of introduced it to us, but we had never heard Ravi Shankar do a concert. But this was something new to the entire audience. It was as close to a kind of ‘born again’ experience that anybody could have had in that audience.But to be honest, it wasn’t just him. It was the tabla player, Ali Rakha. Of course being into drumming, those rhythms I was very unfamiliar with as were most people of those Indian rhythms. So it wasn’t just Ravi, it was the whole thing, Ali Rakha, along with the third performer Kamala (Chakravarty) on tamboura.”

Al Kooper Great set. I was sitting in the audience with another artist. And I’m getting an education because I don’t know much about it. Don’t know much about him just picked up on him through the Beatles. Like everybody else. Watching the musicianship between Alla Rakha and Ravi Shankar killed me. I thought that was amazing when they were trading passages.”

Michelle Phillips Ravi Shankar was the most moving, spiritual experience and it allowed you to get into the pulse and the rhythm and into the deepest meditation. If you opened your eyes and saw people with their eyes closed just listening and being and swaying. No one was smoking, no cell phones (laughs). It was two hours of uninterrupted meditation in the afternoon.

“It probably had a great effect but first of all it was dark in the sense most people had their eyes closed…I’m not sure if it would have mattered if it was day or night. It was just being in the presence of those musicians (Alla Rakha and Kamala) and experiencing a form of music not yet really. The Beatles had sort of introduced it to us, but we had never heard Ravi Shankar do a concert. But this was something new to the entire audience. It was as close to a kind of ‘born again’ experience that anybody could have had in that audience.”

Peggy Lipton: Monterey reached its climax for me when we took something in the early afternoon and there was a light drizzle and we went to hear Ravi Shankar. I remember I left my body. That was it for me. It was beautiful, peaceful and chilled everybody out. Ravi transported me. It was gently raining and he transported everybody. We were all taken there. It was like we were put on a spaceship and driven to another planet.”

Michelle Phillips: Our set was very disconcerning because Denny didn’t get there before 45 minutes before we went on. We had not rehearsed or performed together in three months. We had not rehearsed and we had Larry Knechtel, Joe Osborn, and Hal Blaine, and with our regular band. They were added, and although these guys knew our music we were not used to doing a concert with them. It was very awkward. And, of course, we did the concert, and I knew things were not going well, or great, but the mood of the audience was so good and happy, that they bent for us. Scott McKenzie came out and sang ‘San Francisco’ before our last number ‘Dancing In The Street.’

“I know when I came off stage I just cried and cried for two hours. And then I finally stopped, ‘you know, Michelle, I know it wasn’t a great concert, but get over it. What’s wrong with you?’ And, that’s when I realized I was pregnant! (laughs).”

A few weeks after his visit to Monterey, Eric Burdon sang and wrote, with his band members, “Monterey,” about the feativities, produced by Tom Wilson. MGM Records even pressed the label’s first stereo 45 RPM single that summer.

Jerry Heller: I think that Monterey said to the suits this is the future. You guys better get on the train or you’ll be back releasing records by jazz acts. And the funny thing is, like the guys who were successful at Monterey like Clive Davis, Mo Ostin, Joe Smith, Jac Holzman, guys like that, to this day are still the most important guys in our business. So, Monterey not only was a springboard for acts but a springboard for executives. And, up to that point the agents were the power. You had to have relationships with agents but after Monterey you had agents leaving with their acts to become managers.

“If Monterey taught us things, it was things that we learned from it that we adapted to the real world. Remember: it was a non-profit, and those of us on a different level said ‘OK. Why can’t we do this and make money?’ That’s why it’s so important because it showed that people could get together and that it could be peaceful and nice, black and white, English and American, northern and southern, and everything just worked and all we really had to do was adapt the financial aspect of it to Devonshire Downs [June 1969] and it became a huge profit kind of venture.

“The influence and impact of Monterey impacted other festivals that followed. I represented Eric Burdon and maybe even Paul Butterfield at that time, or a bit later. Also Lou Rawls and I know I represented Moby Grape.

“There’s one thing that people forget about Monterey that is an astonishing fact. And, the more that I think about it the more it astonishes me: I mean, look at what that festival did. The impact Lou Adler has had on everyone’s life. Dig this, man. There were only 7,000 people there. Sitting in chairs! Wow! It is mind boggling that this festival, where people played for no money, in a day when Bill Graham was transforming the industry from a bunch of hippies into legitimate businessmen. What Monterey did was awaken a whole generation of dope smoking hippies to the fact that music could be big business. At the festival you had label heads, a few agents like myself.”

Clive Davis: Oh, my goodness, it’ still many years ago but vivd in memory. I was seeing music change, but I was waiting for the A&R staff to lead into these changes that were showing evidence in becoming important in music. So when I really came to Monterey not knowing what to expect, but seeing a revolution before my eyes that became evident as artist, known or unknown, too the stage. I realized in effect, without it sounding cliche, it became very clear, whether it was an epithiny, whatever. Because it was the electrification and amplification of the guitar. Simon & Garfunkel were folk. All of a sudden seeing (Jimi) Hendrix, Janis Joplin and Big Brother and the Holding Company, and the Electric Flag, and the artists that were there, there no was no question that the predominance there was a change in contemporary music. A definite hardening, edgier, rockier amplification that was taking place that truly was signaling a major revolution in rock music.

I had no idea what awaited me. I had no knowledge of what was going on in San Francisco, for example. So I really was going with my wife to spend a three day weekend enjoying I think the first pop music festival. And going to do it with Abe Somer and Lou Adler. When I saw the crowd, it was visually stunning, the dress and the attitude.

“When Janis (Joplin) took the stage, it was an unknown group to me totally, Big Brother & The Holding Company, and right from the outset it was something you could never forget. She took the stage, dominated, and was absolutely breathtaking, hypnotic, compelling and soul shaking. You saw someone who was not only the goods but was doing something that no one else was doing. With that fervor, that intensity, and impact,

So yes, that in effect, coupled with everything around me, the way people were dressing, what was going on in Haight Ashbury, the spirit in the air, and the feeling.

“I just said, ‘You know, I am here at a very unique time. I’m feeling it. I’m feeling it in my spine.’ I’m feeling it in my sense of excitement. I’m feeling it in the impact, it’s not only musical changes, but in society changes, and I in effect said, ‘this is really, although it sounds hokey or cliche, this is the time that must mean that I’m gonna have to make my move.’

“There’s no question that the primary signing was Big Brother and Janis Joplin, but the Electric Flag was very powerful with Buddy Miles on drums, and Mike Bloomfield on guitar. Laura Nyro was not great at Monterey and I didn’t come away with the feeling I must sign here then. I was aware of her through Monterey, and subsequently came to know of her more particularly through David Geffen, who managed her and when she came to my office to play her material and her songs, it really was the listening of her songs that overcame what had been a negative in person at Monterey.

“The whole experience if one asks, you know and catalogs, or thinks back on most meaningful experiences in your life, it would rank up there at the top. The impact for me afterward was that I realized that I was in on something unique, possibly revolutionary early. But, I quietly signed the Electric Flag and having been aware of what I had just seen at Monterey, I then found myself at an auditioin in the Village of the group that was known as Blood, Sweat & Tears. So, Blood, Sweat & Tears, with Steve Katz and Al Kooper was also using horns and a fusion of jazz with rock in its purest form when Al Kooper was a member.

“There’s no doubt that the knowledge that I had from personally being at Monterey opened my eyes to all the prospects and really the signings of those groups and Santana, and then Chicago, and along the same way and a lesser level, Johnny Winter, Edgar Winter, and Boz Scaggs, and It’s A Beautiful Day, and led to the Grateful Dead in a different context. [Later signing to Arista Records].

“Monterey was very different and unique. The success of the artists I signed at Monterey gave me confidence that I had good ears. It was there’s no question I was going to get confidence from nothing else. I mean, basically, that was a move I had made, and the fact that they came through in a resounding way, and were critically welcomed as well as commercially they reverberated, there’s no question that the streak that I was in with each of them making its mark in an important way lead me imperically ‘cause I had no idea I had ‘ears.’

“I had no idea that I could do this. It never occurred to me that I would be doing it, and so that as each step came through it embolded me and gave me the confidence to trust my own instincts. And, that’s the only way that I’ve ever done it. Because obviously up until that time my background was totally different and it was a talent that I never knew I had. And as each came through it embolded me that I this was something that I not only loved doing but I had a talent for.

“Monterey is a without question probably the most vivid memory from a career point of view, from an emotional point of view from a character effecting point of view that I’ve ever had.”

Jerry Wexler: All credit to Clive Davis because he grabbed up what was potential rock super sales in those groups that he signed. He was smart enough to do that. It didn’t interest me maybe I wasn’t smart enough to hear it so I missed out. He put his label at the cutting edge of rock although I bid on the Electric Flag and nearly hooked one fish.”

Johnny Rivers: After the Monterey Pop Festival everyone ran to San Francisco after that. It was almost too late. I mean, there were a lot of interesting groups coming out of there Quicksilver, and I had scouted Big Brother before the event. A&R man Nik Venet, who produced my first album, was at Capitol had something to do with Quicksilver signing to the label. At Monterey I saw Clive Davis jump out of his seat, I was standing in the wings of the stage, and after that, man, he was on Janis like a cheap suit.

“Backstage there were several long picnic tables that had food where we all sat around and talked. What’s interesting is that. Otis Redding was so soft-spoken and low key, so were Booker T and all the MG’s, but when Otis hit that stage he exploded like an atomic bomb. He literally reached out and grabbed the audience. Show wise he was my favourite of anybody on that show. He was wearing a green suit and tie, such a contrast from all the hippie stuff everyone wore.

“But I wish there had been more of the blues, and the Motown element, John Lee Hooker and people like that featured at this thing. When you got down to it, the highlights were the acts that were still playing the blues, Otis Redding, Janis Joplin and Big Brother. I loved Lou Rawls, who Nik Venet signed to Capitol when he was playing at Pandora’s Box, and he was always great. Again, Lou came out with a suit and tie, kind of an old jazz and blues guy. How can you not love him? He was always a great entertainer. Blues Project was excellent.

John Phillips and Lou Adler worked well together and you have to give them credit. Not only did they pull it off but they did it in good style. It came off without a hitch, man.”

Peggy Lipton: Monterey did change me. I’ll tell you what I felt. In one way we were all on the same page. We’re all going for the same music. And yet there was a loss of innocence.

“I think with Monterey Pop everybody was brought together in a very loving way. It still had the stamp of we love music and we want to be around music I think and we want all of us to be the same. Yes we can idolize our people but we’re really all the same. Because we are the music. And then after I felt change. Things were consolidated. Like, OK, every weird person I loved now everybody loves them. And that’s what I think changed the most. Is when it became exposed. Jimi Hendrix, Laura Nyro. That’s when it changed.

“Even though I came back from Monterey with a feeling of love and music, and we’re all on the same page, it was also like, ‘OK. Everyone knows about this. This was not a hidden thing. Just a little concert on a hill.’ This was a major commercial ‘Let’s put it out there.’ And so I felt both. I felt connected more with the music and also it had changed. And it was different for the people at Monterey and the music of Monterey, too.

The business changed after Monterey.”

Mickey Dolenz: I remember Ringo (Starr) once, years later, telling me how the music business has changed so much. ‘You know, all you had to do in the old days was show up with your drums and you were in the band. (laughs). And, that’s true.”

Andrew Loog Oldham: The festival was incredibly busy, productive, life-changing, exhilarating and relaxed; I do not think that ever happened again. The focus was incredible; the mission was God given. We had never been given that type of responsibility before and there was no way our side was going to be let down. Monterey Pop gave service; it still does. I remain oh, so proud I was there and was a small part of it. Otis; the Who; Jimi Hendrix… every time I think of the music I remember the sea of faces and the rhythm of one of the crowd. These white kids in the audience were in school. We all grew from the diversity presented in those three days.”

Rodney Bingenheimer: The Monterey feedbag was great. There were tons of fruit and all the strawberries you could eat. Everybody was treated very well. Everyone was peaceful and happy. I saw hippie architecht Gypsy Boots, and Cleo Knight from Green Power, a food cooperative. He was out there on the lawn handing out peanut butter sandwiches. Both were from the L.A. Love Ins.”

Robert Marchese: The thing is, the biggest selling album of that whole event was Hendrix and Redding, and the liner notes by Ralph J. Gleason said it took both of them from rumour to legend.

“At Monterey people started seeing the dollars. Prime example Albert Grossman smiling at Joplin knowing he’s got a million dollars there. Like I told your boy, Andrew Loog Oldham after the Stones played the Long Beach Auditorium in 1964 or ’65, ‘What do you think?” And I said, ‘I think you got a hundred million dollars staring you in the face.’

“When Hendrix later played the Hollywood Bowl, and Mo Ostin and Joe Smith were sitting right in front of me. And besides them were two little white chicks. Like ‘Valley beach bunny blondes.’ And Hendrix started playing, and believe me Harvey, when Hendrix started playing they started cumming in their pants. And, I leaned into Mo’s ear and Joe’s ear, and said, ‘this is why you got millions of dollars staring you in your face. This is the first time these two chicks ever got turned on by a black cat. (Laughs). ‘He doesn’t carry a razor blade, he’s awfully good lookin’.”

Chris Hillman: After Monterey we did the Philadelphia Folk Festival with the Burrito Brothers. I didn’t do Woodstock, and I remember Gram Parsons and I were sharing a house in the San Fernando Valley (De Soto Avenue), and Woodstock was on the news. The situation there. We were laughing, and I said, ‘That’s no Monterey.’ And it wasn’t! There was a sense of commaraderie at Monterey.

“I saw Paul Butterfield at Monterey and we had worked with Paul the one time when the Byrds really came to the plate. Which was when we did a week at The Trip and Butterfield’s original band and they were so good. Smoking. Michael Bloomfield doing answer solos with Butterfield on harmonica. They were so good and the Byrds…The one time in our whole career that we played every night at our peak. It wasn’t a competition. It was two different kinds of music. We went ‘oh my God. We played good.’ That was when the Byrds really jelled and really got together that week at The Trip. There were other times, but I always remember that so distinctly. Butterfield. Great band. I studied that first album. I got to know him a little bit.

“I remember doing a music festival with Butterfield in 1969 in Palm Springs, with the Burrito Brothers. I remember walking with Paul to the promoter’s tent and he’s got his brief case with a 38 Colt piece in it, and I said to myself, ‘this guy really did work on the south side of Chicago.’ Oh…Here we are in the peace and love bull shit and here he’s got his 38 loaded to go and collect his money!’ This guy is real. A real blues guy!”

Andrew Solt: What Lou Adler and John Phillips did was that it was the precursor to Woodstock and the big stuff that came about. This thing was naive, small in retrospect; it was really exciting because it was beautiful and not marred by any negativity. I never thought about the money or nonprofit. I then started reading Billboard and later Rolling Stone and wondered, ‘How do I get into this world?’” [Laughs].

Jerry Wexler: After Monterey, I later got the rights to Woodstock. The soundtrack albums came out on Atlantic on our Cotillion label. There was a lawyer named Paul Marshall, he used to be our in-house council. But we parted ways. And he was not our lawyer anymore, but, nevertheless, he called me up, ‘Listen. Are you interested in Woodstock?’’ It was going to take place in two weeks. Who the hell knew what Woodstock was going to be? He said I could have the rights for seven thousand dollars. I thought about, and bought it for seven grand. I figured seven grand? Let me take a shot. And that was it. I should have grabbed the film rights to but Warners got them. Thank God that I bought Woodstock.”

D.A. Pennebaker: I saw what happened at Woodstock, and I really didn’t want to get involved with that at all. One of the producers [John Morris] of Woodstock saw the film of Monterey Pop and wanted to do a festival.”

Michelle Phillips: When I look at the movie and it’s more fun every time I watch it with more space between the actual event and now. It just blows your mind to re-visit it. And, also, it’s so funny, to look at the movie and see so many people that you’re still friends with.

I think Monterey Pop is a really wonderful film. I saw it two years ago on the big screen in Hollywood for the first time since it came out. You get to see what the festival was really like, and how beautiful everyone felt in June 16th, 17th and 18th were all bright sunny days. You see other festivals and they are rolling in the mud. ‘Monterey Pop’ is so representative of the time, people actually did paint flowers on their faces, put big teepees up, a time of arts and crafts

“You know what, 50 years later the Monterey Pop fund is still generating hundreds of thousands of dollars. It keeps on giving every year. And it’s been managed really well, and you have to give Lou the credit because he has been the one in charge of it. He’s been in charge of the money. It’s a beautiful thing.

“I am so proud to have worked on, and been a part of, this once-in-a-lifetime musical and cultural epiphany, knowing that 45 years later the Monterey International Festival Foundation continues to help young musicians, health clinics, music rooms for critically ill children, and more, all funded by the sales of records, tapes, CD’s, VHS and the DVD box sets of the D.A. Pennebaker-directed film Monterey Pop. The sun has never stopped shining.”

Adler directs the Monterey revenue streaming from the Monterey International Pop Festival Foundation. Everything Adler does on behalf of Monterey has the line ‘On behalf of the ARTISTS WHO APPEARED THERE June 16, 17 and 18, 1967.’

Lou Adler: Just think about it 50 years later and the artists that performed at Monterey those three days in June are still giving back through The Monterey International Pop Festival Foundation. At the conclusion of the festival David Crosby said: ‘I hope the artists know what they have here, the power of it to do good. It’s an international force.’”

Since 1967 the Monterey International Pop Festival Foundation has continually supported arts organizations, music therapy programs and health care subsidies for struggling musicians.

The initial grant went towards a music instruction program in Harlem championed by Paul Simon. Subsequent grant recipients whose initial contact or in name of are in parenthesis and include: Blue Monday Foundation – Marin County initial contact Mark Naftalin, Chicago’s Providence St. Mel Music Program (Otis Redding), UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital – Music Therapy initial contact Gregg Perloff, Another Planet Entertainment, Clive Davis School of Recorded Music at New York University, San Francisco Earthquake Fund (Bill Graham), Texas Habitat for Humanity (Janis Joplin), H.E.A.R. – Hearing Education and Awareness for Rockers (Pete Townsend), New York’s Children’s Health Fund – Mobile pediatric clinics, providing care to homeless shelters, housing projects and schools (Paul Simon), Romanian Angels- initial contact Olivia Harrison, Berklee School of Music – Five week program Scholarship and the Clive Davis School of Recorded Music at New York University.

Organizations such as Arts for City Youth, Childrens Hospital Los Angeles, Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz, Haight-Ashbury Free Clinic, Los Angeles Free Clinic, the Barrio Symphony Orchestra and the Debbie Allen Dance Academy to name but a few have also benefitted.

The MIPF has also provided help and aid to the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz Studies, the Rhythm and Blues Foundation, Steven Van Zandt’s Rock and Roll Forever Foundation, and the Music Cares MAP Fund.

The Monterey Foundation donated a wall mural now on display to the UCLA Children’s Hospital, depicting an underwater concert.

Please visit the officialwebsite, montereyinternationalpopfestival.com.

Harvey Kubernik’s literary music anthology Inside Cave Hollywood: The Harvey Kubernik Music InnerViews and InterViews Collection, Vol. 1 has just been published in November 2017, by Cave Hollywood. Kubernik is also writing and assembling a multi-voice narrative book on the Doors, to be announced on December 8th, and scheduled for publication the first part of 2018.

Over his 44 year music and pop culture journalism endeavors, Kubernik has been published domestically and internationally in The Hollywood Press, The Los Angeles Free Press, Melody Maker, Crawdaddy!, Variety, The Hollywood Reporter, MOJO, Shindig!, HITS, The Los Angeles Times, Ugly Things, Record Collector News magazine, and www.rocksbackpages.com, among others.

Kubernik is a record producer, a radio, film, television and Internet interview subject and a former West Coast Director of 1978-1979 A&R for MCA Records. Harvey has penned the liner notes to the CD releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, The Elvis Presley ’68 Comeback Special and The Ramones’ End of the Century. Kubernik serves as Contributing Editor of Record Collector News magazine and displays articles and essays on www.cavehollywood.com on a monthly basis.

In November 2006, Kubernik was invited to address audiotape preservation and archiving at special hearings called by The Library of Congress held in Hollywood, California).

During July, 2017, he was a guest speaker at The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame’s Library & Archives Author Series in Cleveland, Ohio discussing his 2017 book 1967 A Complete Rock Music History of the Summer of Love.