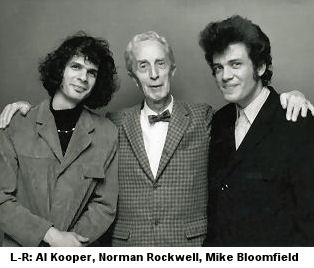

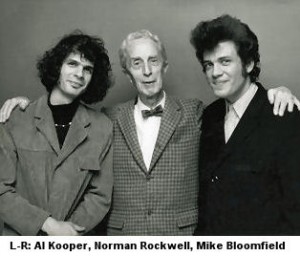

(Photos courtesy of Sony Music)

On March 9th, Al Kooper and Jimmy Vivino with Mike Merritt and James Wormworth will perform in the Los Angeles area at Molly Malone’s (575 S. Fairfax Ave) in a tribute to guitarist Michael Bloomfield. www.mollymalonesla.com

Earlier this century in 2002, nearly four decades after its creation, Columbia/Legacy, a division of the Sony Music label re-released an expanded CD of May 1968’s original “Super Session,” featuring Al Kooper, Michael Bloomfield and Stephen Stills.

Earlier this century in 2002, nearly four decades after its creation, Columbia/Legacy, a division of the Sony Music label re-released an expanded CD of May 1968’s original “Super Session,” featuring Al Kooper, Michael Bloomfield and Stephen Stills.

“Super Session” revealed the collective musical talents of Al Kooper, post Blood, Sweat & Tears, Michael Bloomfield, after his Electric Flag endeavor, and Stephen Stills, immediately after Buffalo Springfield played its final gig that same May. Adding to the seductive power of the disc was an all-star rhythm section of pianist Barry Goldberg, bassist Harvey Brooks and “Fast” Eddie Hoh on drums.

“Super Session” marked the first time in rock ‘n’ roll that a self-acknowledged, let alone, self-imposed jam session devised by Kooper earned its wings as a fully-relaized-and perennially best-selling-album project. Before this reissued, the album had sold 450,000 copies from a $13,000.00 recording budget that then Columbia staff record producer Kooper spent for his cosmic and commercial audio collaboration.

“Super Session” reached number 11 in “Billboard,” and I know a lot of musicians learned plenty from that album.

“Super Session” contains unique re-thought versions of Donovan’s “Season Of The Witch” and Bob Dylan’s “It Takes a Lot To Laugh, It Takes a Train To Cry.” Both tracks were staples of the 1968 FM progressive radio format. The disc incorporates a terrific all instrumental cover of Howard Tate’s “Stop,” a rendition of Gene Chandler’s “Man’s Temptation,” written by Curtis Mayfield, plus Willie Cobbs’ “You Don’t Love Me,” later re-done by the Allman Brothers, plus original songs credited to the team of Bloomfield, Kooper and Brooks.

On the first release of the “Super Session” LP, Bloomfield is the guitarist on “Albert’s Shuffle” through “Really.” He then developed an incurable insomnia and Kooper then recruited Stills, who playing occupied the second half of the album, “It Take a Lot To Laugh, It Rakes a Train To Cry” through “Harvey’s Tune.”

“’Super Session’ is essentially a jazz album disguised as a rock album,” suggests Dr. James Cushing, a DJ on KCPR-FM on the campus ofCal Poly San Luis Obispo. “The jazz element comes from these very gifted players who had not been in bands together but who just knew each other from the scene. And the looseness of the concept, a different band on both sides of the record, shows the kind of improvisational ‘let’s try this and see if it flies’ elements that record labels like Prestige and Riverside were famous for.”

When Kooper brought these musicians to Sunset Blvd in Hollywood at the Columbia recording studio, what happens is they are able to have guitar workouts with Bloomfield and these incredible long jams with Stills, like on ‘Season of the Witch,’ plus ‘Harvey’s Tune,’ which is a jazz tune in a jazz performance. “Super Session” explores the jam potential of it much more. ‘Cause the Donovan recording is about 5 minutes and this is around 11.”

“The tunes by and large become vehicles for improvisation,” Cushing continues.

“And a recording session becomes a way of exploring various shades of the blues. 1968 was a year where Blues in America was having a re-discovery. Fortunately in 1968, authentic 12-bar blues was enjoying, what now looks like a brief and glorious moment of mass media attention. Tremendously helped by the exposure Blues received at the June 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival.

With drummer Eddie Hoh, had played with the Modern Folk Quartet and on the road with the Mamas and the Papas and second keyboardist, Barry Goldberg, on some of the tracks.

Cushing also feels, “So having two keys and a guitar is kind of leading us into a Miles Davis ‘Bitches Brew’ territory. A year before ‘Bitches Brew.’ How is that for an interesting West Coast being a year ahead of the East Coast. Harvey Brooks as bassist, is also the answer to one of the great rock riddles: Which is what does ‘Bitches Brew’ have in common with ‘Highway 61 Revisited?’ And the answer is Harvey Brooks on the electric bass guitar.”

Al Kooper had also played on the Bob Dylan ‘Highway 61’ album with Bloomfield and Brooks. They cut initially cut “It Takes A Lot To Laugh and a Train To Cry” with Dylan, which was originally called or known as ‘Phantom Engineer,’ was quick tempo, and a rocking country-dance tune. And the version on the ‘Highway 61’ LP was a slower bluesier one. What Kooper is clearly doing is trying to resurrect something of the spirit of the earlier arrangement on “Super Session.”

The album also reinforces some of the bio regional oxide magic as it happened in Hollywood on Sunset Blvd.

“So the dynamic impairment goes to the idea that these sessions were very spontaneous and very open,” adds Cushing. ‘Super Session’ remains on my hot-100 list from the whole 1967-72 period… I think it’s having been recorded in LA is kind of an anomaly given Koop’s NY cred, Bloomfield’s Chicago cry and the loose jazz-jam feeling I associate more with Greenwich Village than with Hollywood… popular music strictures or a sense of what was going to be commercial.

“It is also a blueprint in some ways of the path the new FM radio was going. Kooper and his ‘Super Session’ was not music about expressing rebellion against conventional society. This was music that was meant to be apart of a new way of living. This music assumed that the revolution had been fought and won. And that now we could enjoy the fruits of the revolution. Which was the freedom to hear really gifted musicians jam without any obligations to fit into popular music strictures or a sense of what was going to be commercial,” he concludes.

Digital downloading music pioneer and multi-instrumentalist David Kessel, son of master guitarist and jazz icon, Barney Kessel, first discovered “Super Session” in early  summer 1968.

summer 1968.

“Coming out of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band and Electric Flag, Michael Bloomfield was poised to lay down some of his powerfully fluent straight ahead Chicago Blues on tape, in a non hassled atmosphere,” Kessel mentioned in a recent conversation. “Nature abhors a void and Al Kooper filled it with Bloomfield on the ‘Super Session’ recordings. Bloomfield is an extraordinarily great and special blues guitarist, who was really letting loose on the ‘Super Session’ tracks.

“You can feel him just floating over the rhythm section with his amazing blend of his sharp, crisp, tone, and his celestial way of floating his fingers across the fret board in a seemingly effortless manner. This studio album provides Bloomfield an opportunity to really lay it on in a relaxed, but controlled environment, without the stress of pleasing or arguing with fellow band members,” he explains.

“The fact that you get the tracks with Steve Stills, really helps the unique blending of Chicago Blues and Rock Blues, and makes this album a land mark “cross over”, leading to this album being so popular with both Blues and Rock fans. Stills, in the Buffalo Springfield was doing Rock, Pop, and early Country Rock cross over.

“He brought his solid, excellent, ‘A Game’ to the table on ‘Super Session.’

When I hung out for a few days at the Electric Flag rehearsals in Sausalito Bloomfield was using a Les Paul through two Fender super reverb amps. The hipsters experimented with using Fender guitars through Marshalls, and Les Pauls with Fender amps,” David recalls.

“I think a good comment would be “The non Jazz oriented guitar hipsters of this period experimented with using Fender guitars through Marshalls, and Gibson Les Pauls through Marshalls and Fender amps. You can hear a combination of this with Bloomfield and Stillls on this album.”

Al Kooper’s production is very insightful, well structured and arranged, especially since it was done on ‘the fly.’ What a great accident on purpose.”

Al Kooper and Harvey Kubernik Interview 2002 and 2011.

Q. “Super Session” is one of my favorite albums. It showcased your musical relationship with Michael Bloomfield. In 1984 you wrote a song “They Don’t Make ‘Em Like That Anymore” about your friendship with Bloomfield.

A. Well, Michael and I met on the ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ session. I had read about him in ‘Sing Out’ Magazine, and saw a picture of him where he looked a little more rotound then he was when I met him. His brother says he was a fat kid growing up. So we met on the ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ session and really hit it off. So we played together on that.

Q. He blew your mind, didn’t he?

A. Oh, absolutely! I was supposed to play guitar on that record. I packed up my guitar when I heard him warming up. It never occurred to me that somebody my age, and my religion could play the guitar like that. That was only reserved for other people. It never even occurred to me that that was an option for someone my age and my color. I had never seen that, or heard that up to that day.

Q. And you brought Harvey Brooks in to that session as well.

A. That’s right. So, that pretty much ended my guitar playing by and large. I said, ‘well OK, he’s as old as me and he can play like that. I’m never gonna be able to play like that. Thank you, goodbye.’ And, you know, I ended up playing organ on that record, and then I became a keyboard player really that day. So, it was a damn good thing because, you know, that was competition I couldn’t deal with.

Q. On that “Like A Rolling Stone” date, was there a reason why you “played behind the runner” on the track? The organ follows the Dylan vocal.

A. No I did that because I was waiting to see what chord they were going to do. There was no music or lead sheet, or anything. I was just playing by ear and I didn’t want to be the one making a mistake because I was doin’ like a rebel run there. But anyway, we played together on that session, and the rest of the (“Highway 61”) album. Then, I joined The Blues Project, he was in Paul Butterfield’s band. Two blues bands. And we both left the blues bands to start horn bands, which we were both kicked out of again. The horn bands that we started. Very amazing parallel in our careers. Starting from the day that we met. So it seemed to me, in hindsight, looking at that, when I started producing at CBS, that we should make a record together. We were like destined to do something together. Now this whole time we had been friends since we met. I’d go visit him when I was in his town.

Q. And you saw him play with Butterfield many times and was knocked out.

A. Yeah! He ended my guitar playing I’m tellin’ ya. Both of us had just played on that ‘Grape Jam’ album. So that sort of gave me the inspiration to say, ‘why don’t we make a record.’ I wanted to make a record with Bloomfield, and I wanted to make a record that was a very simple, basic record, not a ‘weighty’ record. So inspired by the ‘Grape Jam’ thing, I said ‘let’s make a rock ‘n’ roll record based on the way jazz records are made. You pick a leader, or two leaders, and then you just go in, you pick some songs, you pick sidemen, and you just blow. No rehearsing or anything. You just go in and blow. So I said ‘I don’t want to make a jazz record.’ And I was very dissatisfied with the way he was recorded up to that point.

A. Yeah! He ended my guitar playing I’m tellin’ ya. Both of us had just played on that ‘Grape Jam’ album. So that sort of gave me the inspiration to say, ‘why don’t we make a record.’ I wanted to make a record with Bloomfield, and I wanted to make a record that was a very simple, basic record, not a ‘weighty’ record. So inspired by the ‘Grape Jam’ thing, I said ‘let’s make a rock ‘n’ roll record based on the way jazz records are made. You pick a leader, or two leaders, and then you just go in, you pick some songs, you pick sidemen, and you just blow. No rehearsing or anything. You just go in and blow. So I said ‘I don’t want to make a jazz record.’ And I was very dissatisfied with the way he was recorded up to that point.

Q. This was one guy who was way better in person as opposed to a record. You didn’t think he was recorded right?

A. When I say right, I mean that his live playing was like 300 times better than performance on a record to that point. In my opinion. So, what I wanted to do was put him in a situation where he was uncluttered by his career, and uncluttered by his situation in the recording studio, which must have inhibited him. So I made it as uncomplicated as possible for him. Because that was the goal of the sessions for me, was to get amazing playing out of him like I heard him do on stage. And I felt really vindicated that I had done that. And that’s what I wanted. I did what I set out to do. And, the other thing was, we both had been kicked out of the bands, and then Stills, too. He was out of his band (Buffalo Springfield). So Stills fit in, in a really weird way. Because none of us had anything at stake, and that was the whole point of that record. There was no career thing goin’ on. We just did it because we played music. That’s what’s so wonderful about that. ‘Super Session’ wasn’t made to sell records. It was just made like those jazz records were made for Blue Note, except it wasn’t ‘Blue Note’ kind of music. It was more music that we were in to. ‘Albert’s Shuffle’ is sort of the hit of that side, as time has passed. Although, the song was used twice in the film ‘Sneakers,’ by Robert Redford. That floored me.

Q. Did “Super Session” creep on to FM radio or explode on the free form format in the late ‘60s?

A. Well, see, I had no expectations for that record. I mean just none whatsoever. I just did it because I had a job as a producer and I had no one to produce, and I went in because I thought Michael and I should make a record together, because how our careers were parallel. And also because we were friends, and it would be fun to work together.

Michael brought Eddie Hoh (drummer) in, and I brought Harvey in (bass). I said, ‘you pick the drummer, I’ll pick the bass player.’ Again, sort of like a Blue Note concept.

The most important thing is the playing of the two principals, Bloomfield and Stills. It’s timeless. Bloomfield’ stuff is some of the greatest blues playing that there ever was. And it was a non-vocal Stephen Stills, owing to contractual limitations and restrictions. Which was a very strong thing in that decision. I regretted that a lot that night. But I said if he sings we’ll never be able to put this out. I knew Stephen was a great guitar player and that was the key thing. But I had to take a lot of shit from David Crosby when that came out. ‘Why the fuck didn’t you let him sing?’ And I told him and he didn’t even listen to me.

“Because it was a great period of time and there were great minds working

geographically located in the same place. There was a lot of freedom out on the west Coast, but frankly, ‘Super Session’ could have been recorded anywhere.

In 1997, “The Live Adventures of Mike Bloomfield and Al Kooper” was released on CD, and reissued again earlier this century. It was a late ‘68 live date taped at the Fillmore West on the heels of their “Super Session” studio work.

Joining organ and piano player Kooper and guitarist Bloomfield were drummer Skip Prokop and bassist John Kahn. Carlos Santana and Elvin Bishop also appear on the recording. Highlights include the riveting selections “Don’t Throw Your Love On Me So Strong” and “Mary Ann.”

“Well, you know, that was a weird record,” commented Kooper in 2004. “We sort of did that because people gave us some shit about the confines of the studio, and it was slick, this kind of thing. So I said, ‘let’s go down and dirty and play a gig and record it live. Nobody is gonna yell studio at us for that.’ So that’s what we did. And it actually was a little too down and dirty.”

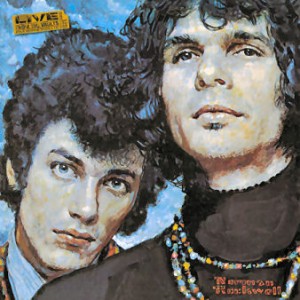

The front cover is a painting by legendary artist Norman Rockwell of Bloomfield and Kooper