By Harvey Kubernik

“RUBBER SOUL – the album that changed the musical world we lived in then to the one we still live in today.” —Andrew Loog Oldham, record producer/manager of the 1963-1967 Rolling Stones, founder Immediate Records, author, deejay, and Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductee.

“Today we think of the Beatles epic as one incredible breathless run, and it did all happen very fast, their 8 or 9 dizzying years,” offered writer and novelist Daniel Weizmann.

“But on close inspection, before Rubber Soul, there was a subtle sense that the Beatles were…almost starting to run of steam, exhausted from all that mop-shaking. And who can blame them? Beatlemania would have driven four less durable souls into an insane asylum. Beatles for Sale, Beatles VI, Help! — the songs are great but some near-invisible identity crisis is at work in them, a groping for more. In an alternate, less beautiful universe, the band might have even thrown in the towel right then and there. Which is partially why Rubber Soul is such a miracle — it’s not just an album, it’s an announcement, that they would not back down. They had stripped down to essentials, learned to stifle their own cuteness, and were ready to push past youth, guided by introspection. They aren’t there yet, but the plot had thickened — and Rubber Soul is the first chapter of Act II, the very best part of the story.”

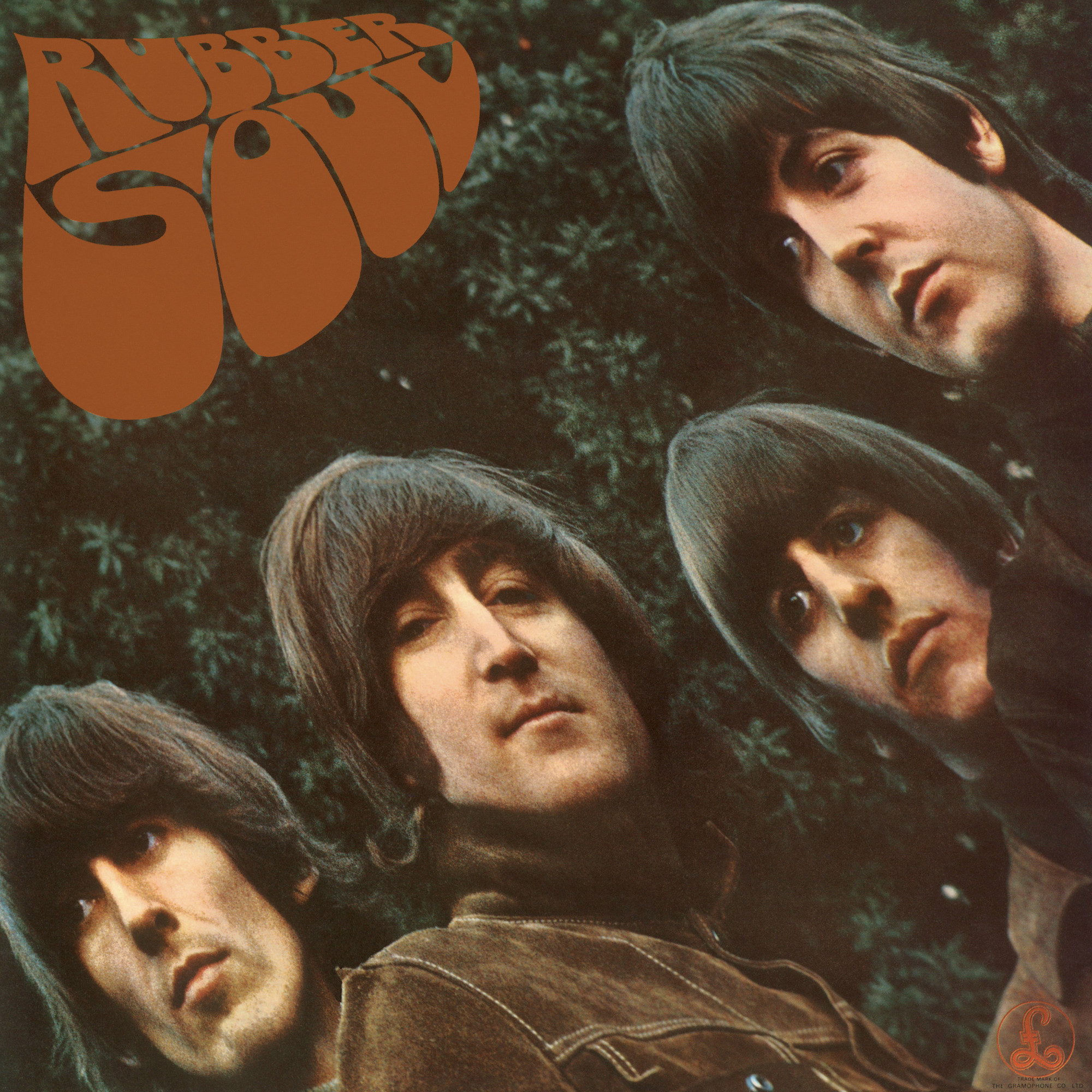

Rubber Soul, released on December 3, 1965, was the Beatles’ first release not to feature their name on the album’s cover, an uncommon strategy in late 1965. The cover photograph was by Robert Freeman in the garden of John Lennon’s home in Weybridge.

In 1997 I conducted an interview with George Harrison. He mentioned he had first heard the sitar instrument on the set of The Beatles’ movie Help! Later that year, he would record with it on the session for John Lennon’s “Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown).”

George told me about his earliest attempt at playing the sitar with the Beatles, “Very rudimentary. I didn’t know how to tune it properly, and it was a very cheap sitar to begin with. So ‘Norwegian Wood’ was very much an early experiment. By the time we recorded ‘Love You Too’ I had made some strides.

“That was the environment in the band. Everybody was very open to bringing in new ideas. We were listening to all sorts of things, Stockhausen, avante-garde music, whatever, and most of it made its way onto our records.”

During 2007, I interviewed my friend Brian Wilson for the 40th anniversary Pet Sounds tour program notes. Brian confessed “Michelle” and “All My Lovin’” were his two favorite Paul McCartney songs and immediately cited Rubber Soul.

‘“Norwegian Wood’ completely blew my mind, and marijuana was around for Pet Sounds. Well, when I first listened to Rubber Soul, I then went to the piano and all I could see were my keys. I locked in with the keyboard and wrote [with Tony Asher] ‘God Only Knows’ in 45 minutes.”

In 1998, I interviewed Elvis Costello in Hollywood during his Painted By Memory recording sessions with Burt Bacharach at Ocean Way Studios. We briefly discussed Rubber Soul.

“I have a perspective on it that someone of my years probably shouldn’t have. I always heard Burt’s tunes in cover form first. And that was important. The stuff that my dad [Ross MacManus, musician, singer and trumpet player who performed with Joe Loss and his Orchestra] brought home were ‘A’ label singles.

“Like the Beatles ones I had, were the non-single tracks like ‘Michelle,’ and songs from Rubber Soul that they [music publisher Dick James’ Northern Songs] thought were better suited for covers than, maybe, ‘Drive My Car’ was. They were sent over on demonstration acetates. Rather than having the Parlophone label, which never pressed ‘Michelle’ as a single, the publisher, pressed an acetate. And that was how small they were thinking about that ‘radio cover.’”

“Firstly, what a fabulous elasticisable title!! Puts it all in the perfect perspective,” volunteered music historian, author and broadcast journalist, Ritchie Yorke.

“Creativity grows. And it shows. On Rubber Soul, we are seeing the beast that became John Lennon’s composing heart is gaining traction and he’s beginning to let it flow on through. How blessed we were that it flowed upon our watch. And in our presence. A wonderful album made most of us realize that there was a lot more to these dudes than just pulling off limp versions of great R & B tunes.’’

“They were the natural progression from the roots of the music,” underscored Blondie’s drummer Clem Burke. “The early recordings spread the gospel of Little Richard, Buddy Holly, and Motown to a new generation of rockers. They are and always will be my muse. I’ll listen to a few songs before a show and get a rush of emotions. They had the best drummer in rock ’n’ roll that really made the recordings creative.”

Engineer/producer Ken Scott is a veteran of Abbey Road and behind the console for many recording sessions of the Beatles beginning in 1964 sorting tapes in the EMI studio library. He attended the “I Should Have Known Better” date, on an invite from engineer Norman Smith, and handclapped with Ringo and Paul for a take that wasn’t used for A Hard Day’s Night soundtrack LP.

Ken Scott’s first day as a second engineer was June 1, 1964, during sessions for A Hard Day’s Night. Songs not utilized in the film: “I’ll Cry Instead,” “I’ll Be Back,” “Matchbox” and “Slow Down.”

At Abbey Road one of his early jobs was “banding,” a task entailing putting exactly five seconds between each track on the albums. Scott subsequently learned the aspects of mastering process. In 1965 Ken worked on Help! and Rubber Soul, before engineering the bulk of The Beatles (White Album).

Q: Ken. You spent a lot of time in the mastering lab that informed how we eventually heard the mono and subsequent stereo discs of the band.

A: The whole thing that one learned from the mastering, first and foremost, was what could go onto vinyl. Because you could put a lot more onto tape than you could on vinyl. You had to watch phase, you had to watch the amount of low end, all of that kind of thing, because it would make the stylus jump. That was really why they out you into mastering before allowing you to engineer.

“The other aspect of it that you learned was about EQ. Tone control. Bass, middle, high end and how you could affect that. What sounded good and what didn’t sound good and how much it took to try and change a sound. After a few days you learned you could make it perfect just by adding one notch as opposed to piling it all on.

“Abbey Road had their own pop shields for vocals. My belief is that they were made especially. I can’t tell you the pop shields around the microphones at Abbey Road made a huge difference, but it’s a combination. Everything starts in the studio. They were so good together vocally to start with and then that just made it so much easier for Norman to get it that much better.

“For me, mono is the way we listened to them. We never ever, as we were recording, listened to it in stereo. Always mono. We only listened to it on one Altec (604) speaker. They weren’t that good and we had to struggle to get things sounding good through those speakers but we knew if we got them sounding good through those speakers, they would sound amazing anywhere else.

“I learned so much from working in mono. Because these days, just take George and John’s electric guitars. If you want to high light the differences between the two of them, you’d put George’s guitar on one side and put John’s guitar on the other side. They’re separated and you can hear the differences between them. When it was the mono, we actually had to make sure we had different sounds on them. Because they’re both coming out of the same source. So, you have to make sure they are very different to be able to hear. ‘OK. That’s John playing here and George playing there.’ We had to work that much harder for the difference than you do in stereo. Anything they recorded at Abbey Road was done on EMI tape. EMI manufactured its own tape and it was incredible. It was really good.

Q: Norman Smith engineered all the Beatles albums ending with Rubber Soul. Norman was responsible for groundbreaking technical changes in their recorded catalog.

A: Every single album he tried to make sound different. He pushed the envelope as far as he could. It was very difficult to make radical changes when he was engineering. Each album got progressively more radical if you like. A change in microphone placements. Absolutely. And using different microphones.

“On the first album he wanted to capture them live in the studio. So, he set them up without baffles and without anything. It was as if they were on stage. That was the first album. Each one was different. To me, the way the Beatles got into experimentation a lot of that came from how they saw Norman changing things. Obviously. they caught the ball and ran with it. Unlike anyone else at the time. But he was the one I think that first instilled in them ‘it doesn’t always have to be the same every album. You can change it sound wise.’ Obviously musically their experimentation with other instruments. Norman was the first pop engineer to record sitar at Abbey Road. He was amazing. He was always pushing it.”

Last decade I interviewed Abbey Road-based engineer Allan Rouse. He emphasized Norman Smith’s role with the Beatles.

“Norman was a musician’s engineer, and had formed his own band in the 1940s. So, for the Beatles’ early sessions, he understood that they had hardly any experience in a recording studio but a great deal in performing live and that is the feel he wanted to capture. I believe the approach Norman took in recording them this way helped them settle into studio life and allowed them to perform in a way that made them feel the most relaxed and I think it shows in their performances.”

Richard Bosworth is a Hollywood-based engineer and record producer who worked with Johnny Rivers, Neil Young, Carlos Santana, Marty Balin, Kim Carnes, KISS, the Knack, and the Hollies at Abbey Road.

“Norman Smith, their first engineer, regardless of his age at the time, he was a young engineer,” observed Bosworth in a December 2023 conversation.

“Norman was not a long-term staff guy at the EMI Studio, who happened to come along in an era and started doing things like closer microphone placements for the aggressive sounds. When you consider Smith went all the way through Rubber Soul. Just Incredible.”

Bosworth points to a piece of equipment engineers Smith, Scott, and EMI Studio engineers had at their disposal capturing other worldly vocals committed to vinyl.

“EMI Recording Studio had a custom-built wind screener pop filter closer to the mike being the plosives where certain sounds would become very powerful and actually collapse the microphone capsule,” Richard elaborated.

“You could get the vocalist closer to the microphone and a more in-your-face sound. They came up with a metal windscreen that had two different screens and two different meshes on them and different physical angles, where the one metal mesh was rounded and one was flat.

“The patterns of the mesh were diagonal to each other. Bolted tight onto the microphone, made with custom metal for EMI Studio. People started noticing quickly that moisture would get on the microphone capsule and you’d have to replace the capsule. Any pop filter changes anything to a certain extent. Unlike screen pop filters made out of foam, these were made out of metal and certainly not dampening high end. Those are unique.

“One of the other reasons the Beatles’ recordings sound so good still to this day,” Bosworth maintained, “is that the tape machine format was one-inch 4-track—a much wider tape width per track than any other analog tape format that has ever been conceived. The equivalent of 24-track would require that the tape format be six inches wide to get the same fidelity that the one-inch 4-track provided.

“Norman Smith engineered virtually every studio performance of the band from 1962 through 1965. On Rubber Soul, Smith captured innovative new sounds such as fuzz bass guitar, sitar and distinctly dry vocals.

“There’s a definite delineation point in the record production and musical instrument sounds for The Beatles with the release of Rubber Soul. There were hints of what was to come on Help! (‘You’ve Got to Hide You’re Love Away’). Many influential American musicians of the day believe the U.S. version of Rubber Soul is one of the greatest albums ever (including Brian Wilson). In fact, the opening songs on both sides of the American Rubber Soul, ‘I’ve Just Seen a Face’ and ‘It’s Only Love’ respectively, are two tracks from the English Help! LP and set an introspective acoustic tone for the American release.”

Big sonic changes are introduced on Rubber Soul with the actual electric guitars and the guitar amplifiers the band adopted at this point. Up until now they had stuck with the musical instruments they’re famously known for. Gretsch and Rickenbacker guitars for Lennon and Harrison and Hofner 500/1 bass guitar for McCartney, via various Vox guitar amplifiers. Rickenbacker had made a left- handed 4001S electric bass guitar for McCartney that he received on the Beatles 1964 U.S. Tour and except for one song, “Drive My Car,” he used his new Rick bass exclusively on Rubber Soul. As the Rick is solid body as opposed to the hollow body Hofner, it gave a more solid electric bass sound than the more acoustic qualities of the Hofner.

“Whereas McCartney gravitated to Rickenbacker, Lennon and Harrison moved on to Fender, Gibson and Epiphone electric guitars,” explained Bosworth.

“The Beatles were aware of the brand of American guitars and amplifiers used by their idols Buddy Holly and Chuck Berry. However, these were not available in England until 1965. Harrison and Lennon acquired twin sonic blue Fender Stratocasters which they used to great effect on “Nowhere Man” (U.S. single/British album release.) Harrison added a Gibson SG Standard and a Gibson ES-345-TD to his arsenal. Lennon, Harrison and McCartney all purchased Epiphone ES-230-TD Casino guitars and these became their ‘go to’ instruments for the next several albums and the 1966 tours.

“The Epiphone Casino became Lennon’s main guitar for the duration of the Beatles career and he used it exclusively on his first solo album and the ‘Cold Turkey’ Plastic Ono Band single,” underlines Bosworth.

“During the Beatles’ 1965 U.S. tour, Harrison was given a second Rickenbacker 360-12 by a Minneapolis radio station and he utilized it on ‘If I Needed Someone’ (British album release) in a tribute to the sound of the Byrds.

“Aware that many American musicians used Fender Musical Instrument’s guitar and bass amplifiers they began to buy a steady supply that continued right through the Abbey Road album. McCartney got a blonde Fender Bassman amp and soon after Harrison and Lennon bought two Fender Showman rigs with 15″ JBL D130 speakers. They still used Vox amps as well. They had an endorsement deal with Vox since 1963 and once that was in place The Beatles never appeared live without Vox amps. The company always supplied the band with their latest models and during this period both Lennon and Harrison received the ultra- rare Vox 7120 electric guitar amplifier and McCartney was given the equally rare Vox 4120 bass amp.

“I think vocally the Beatles are influenced by Bob Dylan during this period,” suggested Bosworth. “They had noticed there weren’t effects like reverb and vocal delay on Dylan’s vocals and it gave his performance an intimacy that really suited the lyrics.

“The Beatles own lyrics were taking on a new depth and they felt this kind of vocal sound would accommodate the new songs. They would say to George Martin and recording engineer Norman Smith ‘Why do our vocals have to have echo on every song? Why do we always have to do things the same way every time?’ With the release of Rubber Soul, the Beatles signaled they were not going to be artistically trapped by their success.”

“There were actually three Bob Dylan LPs in 1965: Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited, and Rubber Soul,” suggested poet and deejay, Dr. James Cushing.

“Of course, I don’t mean that literally – but it may be helpful to think of them as an unintentional set of three. They all share roots in folk traditions (lots of acoustic guitars) but they’re breathing the air of pop/R&B/art-song/blues, and the blend they achieve contain both the sophisticated complexity of art and the accessibility of popular culture. These were the albums that marked the emergence of Rock as an art form with appeal to thoughtful adults.

“Look at the covers. Dylan: hermetic, highbrow, literary, arrogantly challenging. The face is a provocation, whether framed by a cat and a woman in red or a Triumph motorcycle T-shirt and a headless photographer. Will you dare to meet my eyes? The Beatles: distorted, hair longer than long, eyes turned away – all except Lennon, looking at us but also looking within, clearly baked. Will you dare to look at what we’re seeing?

“Dylan created a novelistic mass of characters and situations in ‘115th Dream’ and ‘Desolation Row,’ but the Beatles began developing their own individual characters. Lennon could not have shown the Continental grace of ‘Michelle’ any more than McCartney could have summoned the wry confession of ‘Norwegian Wood.’ Harrison, for the first time, assumes the role of spiritual pundit, and tells us to ‘Think for Yourself.’ The songwriting Beatles debut their distinct sensibilities here; the seeds of the White Album, and their later breakup, are thereby planted.

“I agree that this LP is the first one where the US edition is aesthetically superior to the UK one – deemphasizing rock (‘Drive My Car,’ ‘What Goes On’), highlighting an introverted-acoustic folk sensibility, and resulting in a more coherent 12-song, 30-minute statement. Lennon’s ‘Run for Your Life’ is the only false moment – a blast of misogyny that sits poorly with the tenderness of ‘In My Life’ or ‘Wait.’ (It’s also a blatant plagiarism of ‘Baby Let’s Play House’ from Elvis’ Sun sessions.) Might not ‘Yesterday,’ another song from the UK edition of Help!, have made a more fitting end to the album?”

“Rubber Soul seemed the first Beatles’ album released in the U.S. more or less to correspond to its U.K. counterpart, 1965 being rather late in the game to issue the themed Beatle musical think pieces recorded at the same session rather than grab-bags of singles from one and meat and potatoes from another two or three,” posed photographer and music journalist Heather Harris, who witnessed the Beatles’ 1964-1966 Southern California concerts.

“Therefore, American fans could rejoice simultaneously with their British our new musical heroes waxed experimental while still remaining front runners in the pop game. Brian Wilson wasn’t the only one who noticed. Harpsichord, Franglais, actual threatened violence, Dylantries et al. stewed and brewed through … the world’s best- selling pop band?! We teens reveled in the high caliber of largesse from these songwriters, only to find it successively topped in the 2 years to come with Revolver and Sgt. Pepper. Acute bliss.

“Lastly, psychedelic font lettering on an anamorphic stretch photo by Robert Freeman, exponent of natural and directional lighting, and director of Performance-type precursor insofar as it deftly balanced fey pop culture and butch violence, The Touchables. That cover: pure inspiration, in and of itself and to anyone interesting in the field of graphic art, photography and trailblazing visuals…”

“Remember when record stores had separate sections for Mono and Stereo? It was in one of them I bought my first Beatles record. I was living in Milwaukee, working as an actor at the Milwaukee Repertory Theatre and reading beatnik poetry, Ferlinghetti, Corso and others, in schools,” recalled music scholar, photographer, deejay and author, Roger Steffens.

“My friends were nearly all artists of various edge-busting kinds, with music as a common chord. We had begun dropping LSD and looked for albums that understood that experience and turned it into art. But that album would be Revolver. Rubber Soul was the pot album. At least according to John.

“By 1965 we knew that the Beatles were always trying to top what they had done before. My copy is mono, just the way they wanted it to be heard. On the bottom of the back cover, it reads: ‘This monophonic microgroove recording is playable on monophonic and stereo phonographs. It cannot become obsolete. It will continue to be a source of outstanding sound reproduction, providing the finest monophonic performance from any phonograph.’ (italics mine). Essentially an acoustic album, half a century later, it fulfills that promise.

“It was the album that took the Beatles’ audience out of the One Direction screaming teenage groups category and began insinuating their seductively sumptuous sound into hipsters’ pricked ears.

“It was the first album in which the boys took over everything, including the cover. Oddly enough ‘rubber’ soul meant ersatz soul, plastic soul. But there’s nothing insincere in these tracks. It’s George’s favorite album, heavily influenced by herb.

“‘Norwegian Wood’ is John’s first confessional, predating his first solo album by half a decade and introducing a nascent eastern influence as George plays a sitar on record for the first time.

‘“Think for Yourself’ utilizes the LSD prophet Timothy Leary’s famous dictum, coming into notoriety at that time: ‘Think for yourself/question authority,’ although it’s ostensibly a love song. The Beatles were taught early to use personal pronouns in their titles – ‘I, Me, Mine,’ You, Your – to create the most appealing way to control the emotional effects of songs about the various aspects of love. As Bob Marley once noted, ‘what’s so bad about telling people to love one another?’

“Another eastern instrument is introduced in ‘The Word,’ on which the only person who can legitimately claim to be The Fifth Beatle, producer George Martin, plays the harmonium. Here love is depersonalized to a philosophical principle. “It’s so fine, it’s sunshine, it’s the word love.” And Paul declares, “I’m here to show everybody the light,” his first admission that their music is meant to be transformative and enlightening. Teacher Paul.

‘It’s Only Love’ is another sneaky attempt by John to include some drug references: “I get high when I see you walk by,” but not as overt as the smoke-sucking licks on “Girl,” a ravishing ballad about sexual frustration. And then there’s the Beatles singing tit-tit-tit-tit in the background, wanting so much to shock like kids in middle school, smirking through the take.

‘I’m looking Through You’ is like an acidic revelation, seeing the image behind the illusion. And then there’s the transcendent ‘In My Life,’ which John considers his first real major piece of work. With George Martin on an Elizabethan piano solo recorded at half speed, “In my life, I love you more,” has become a wedding perennial.

“But the album seems a bit unbalanced at the end, with the misogynistic ‘Run For Your Life’ and its harrowing, no-doubt-about-it threat: ‘I’d rather see you dead little girl than to be with another man’ a death knell for “I want to hold your hand” sentiments. And a prophecy of ‘Helter Skelter’ proportions.

“Rubber Soul is an album I shall never stop playing. Like Astral Weeks and Moondance, it and Revolver are of a pair, and of a time; irretrievable and absolutely essential,” concluded wordsmith Steffens.

“With their own, unique version of Rubber Soul American Capitol finally got it right,” claimed proud Canadian Beatlemaniac Gary Pig Gold.

“Up until then of course, all of Parlophone’s precious Fab LP’s had been thoroughly sliced, diced and, I quote, Prepared for release in the U.S.A. with the assistance of Dave Dexter, Jr. With varying degrees of success, shall we say. But no sooner had John Lennon caught sight – not to mention sound – of Capitol’s slap-dash ‘very special movie soundtrack souvenir album’ for Help! than the (in)famous Dex was given the heave-ho by the powers-that-were at EMI’s London HQ, leaving substitute Capitol international A&R exec Bill Miller’s staff to assemble a Rubber Soul for 1965’s all-important North American Christmas market.

“And what a fine job they did! For the first time leaving the Beatles’ U.K. cover photos and graphics of choice intact – one of the Sixties’ most iconic long-playing images, absolutely – Miller’s men cobbled together what some still profess to be a ‘folk-rock’ blend containing two left-over numbers from the British Help! LP while removing several of the rougher, as in fully plugged-in tracks from Rubber Soul U.K. In doing so however, the core of the band’s intricate original running order was wisely left as-is and the ultra-refreshing result was a slightly more ‘mellow’ perhaps (‘mature’ was the word many startled reviewers used in ‘65) package from those hitherto poppy-go-lucky mop-tops.

“Nevertheless, discriminating ears from Los Angeles to the Canadian Laurentians immediately took notice …not the least of which to the very air of savvy sophistication – though some detected second-hand jazz-cigarette smoke as well – which permeated the entire proceedings, from Lennon’s provocatively fishy-eyed ‘I dare you to find anything wrong with this’ gaze on the front cover to the Strat ‘n’ sitar-soaked sounds within. Why, for starters as we all know, no less than a certain Beach Boy, upon first removing Rubber Soul from his turntable, immediately vowed to ‘answer’ it asap by himself making ‘the greatest album ever!’ And if, because of that challenge alone, the American Rubber Soul should be hailed, even a half-century later, as a resounding, unqualified utterly game-changing success.”

“Rubber Soul is the Beatles album that illuminates the simple fact that when you strip away some of the early Beatles raw electric energy and manic song power — you simply find that more endless talent awaits you, to positively blow your mind in this new semi-acoustic setting,” stressed music and radio business veteran, Elliot Kendall.

“Focusing on the American version for now, Rubber Soul current personal favorites include the defiant Harrison track ‘Think for Yourself’ with its attitude-packed 6-string fuzz bass (furiously played by McCartney) and subversive funky rhythm section. Is it the Ghost of Motown’s Funk Brothers (specifically bassist James Jamerson and rhythm section spirits) who pay a brief mystical visit to this musical space? Take a closer listen next time you spin.

“‘The Word’ is positively pulpit-pounding evangelist action. This track bears repeated listening for a multitude of reasons, a few listed here: Lennon’s vocal is nothing less than a man let loose with the truth, with the driven need to share his newfound revelations with the world. So…how about a stack of those bad ones for our research, Winston O’ Boogie?

“Lyrical intimacy rules the aura of this album. On ‘Girl’ Lennon is positively confessional. The Greek-inspired acoustic guitar work (evoking an old world bouzouki) only serves to underscore the emotion and reflective surrender of this piece.

“Romantic disillusionment haunts both McCartney-led tracks ‘You Won’t See Me’ and ‘”I’m Looking Through You,’ both tracks said to be inspired by the state of his then-relationship with Jane Asher. Both are loaded with daring innovation and a new sophistication previously unheard in pop recordings, as with the entire album.

“Rubber Soul had no single released in the U.S., which is bewildering in hindsight,” admits Kendall. ‘“Drive My Car’ and ‘Nowhere Man’ (both included on the UK versions) were released as singles on both sides of the pond, but not included on the American LP pressings.”

“‘Day Tripper’ and ‘We Can Work It Out’ were already available as a two-sided singles,” reminisced writer Paul Body. “Help! had been out for the Summer of Yesterday. Now Rubber Soul to end the year on a quiet note. Of course, the import and domestic versions of Rubber Soul were different but that was cool. You either bought domestic version at Sears or bounced over to Lewin Record Paradise on Hollywood Blvd. to get the import.

“It seemed like a perfect Winter album, all dark and moody. They had come a long from ‘I Want to Hold Hand.’ It was cool to hear ‘Nowhere Man’ on the album before it was a single, never will forget that when I saw them LIVE George Beatle played that cool lead break and I remember you could hear that bell sound at the end, even in Chavez Ravine. The harmonies were stunning on ‘If I Needed Someone.’ The Hollies covered it but the Beatles version was the ONE. ‘Michelle’ was great to listen to on a cold winter night, felt like Paris.

“Yeah, the Mop Tops had come a long way. The Country stomp of ‘I’m Looking Through You’ made you want to dance, the European grimness of ‘Girl,’ sounded like something from a Truffaut movie, all black turtle neck and black beret chic. Francois Hardy. ‘In My Life’ was sad then and it’s sadder now. Yeah, Rubber Soul was pointing towards the future and what a future it turned out to be.”

Rubber Soul is a complex album musically. It’s unexpected chord sequences made it especially attractive to jazz musicians who dug the LP.

Alto and flute player Bud Shank had a MOR hit single with “Michelle;” the Paul Horn Quintet cut a rendition of “Norwegian Wood.” Flautist Horn was a practitioner of transcendental meditation and was with the Beatles on their India trip in 1968.

English jazz pianist Gordon Beck in 1967 released Experiments in Pop, with a version of “Norwegian Wood (The Bird Has Flown)” featuring guitarist John McLaughlin.

The Big Band Swing Face 1967 live album by Buddy Rich and his Big Band contained arranger Bill Holman chart of “Norwegian Wood.” Duke Ellington and his orchestra on the February 22, 1970 Ed Sullivan Show performed “Norwegian Wood” during a dazzling medley of Beatles’ tunes.

“We did Rubber Soul Jazz for Randy Wood who had Mirwood Records,” recalled keyboardist and arranger Don Randi.

“Wood was formerly with Vee-Jay Records. I loved the music from the start. If not the first fusion album one of the first to combine the feeling of jazz and rock together. Marshall Leib worked for Randy Wood at the Mirwood label and he heard me playing these songs at Sherry’s Restaurant on the Sunset Strip and asked if I would like to do the album.

“Half the people on the Rubber Soul Jazz sessions were American Federation of Musicians Local 47 Hollywood union members. I arranged it. Marshall produced it. Dave Hassinger was the engineer. We could do the music instantly and it made it easier for everybody else. We stayed constant so that they got used to dealing with a constant rhythm section. A band that plays together and listens to each other. Because we had the ability to do that. We didn’t have to do 20 takes.”

“In 1967 ‘…twenty years ago today’ represented a lifetime to a twenty-year old listening for the first time to the Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band lyrics,” pondered Michael Fremer, deejay, writer, editor of The Tracking Angle.

“Sixty years ago, was then an unimaginable dark expanse of time. Yet here we are, on the Sixtieth anniversary of Rubber Soul’s release, still writing and talking about an album that today twenty year olds still listen to — some of us lucky enough to be able to pull from a shelf and play the very vinyl copy we bought in the fall of 1965 and hear it sounding as clean and fresh as it did that memorable first play (and sounding more life-like than any tinny digital reissue).

“Sixty years later it feels to me like yesterday (though my troubles don’t seem so far away) that after counting down the days to its arrival there, I drove down the hill from Cornell to a hole-in-the-wall Ithaca, New York record store to buy that copy.

“Back then, you may have heard on an AM radio station about a record’s release (we listened to ‘clear station’ WWKB 1520, in Buffalo, New York for all things Beatles) but you didn’t get to see the 12×12 cover art until you confronted it in person.

“I can still see myself standing in front of the counter gasping at the solemn faces of the even longer haired quartet, who last time I met them were like carefree kids. ‘Uh oh,’ I remember telling myself, ‘What’s wrong? Did I miss something? What happened? Rubber Soul? They don’t look so bouncy. Am I going to have to get somber now too?’

“I remember putting the record on my Dual 1009SK turntable and the Koss Pro 4A headphones on my head and lying in my frat-house bed for that first listen. ‘What? Is this a country and western album? Is that why George is wearing a cowboy outfit on the back cover?’ Then comes a sitar (not that I knew what it was) and ‘having a girl’ or her ‘having me.’ ‘She said it’s time for bed?’ Not in my world! What’s that weird fuzzy sound? ‘The word is good?’ Lyrics in French?

“And that was just side one!

“It’s doubtful young streaming music listeners today will remember sixty years hence where they were when they first streamed music that a half-century later still holds meaning for them. They pay nothing and sixty years from now they will have nothing.”

In his SiriusXM satellite radio duties, deejay and guitarist/musical director in Bruce Springsteen & the E Street Band, Steven Van Zandt programs Beatles’ recordings, devotes shows to them, and spins their catalog on vinyl and in mono on his Underground Garage channel.

“As far as the Beatles in mono, there was something physical as well that the analog medium communicated that digital never will,” emphasized Van Zandt.

“It doesn’t really matter of course unless you’re listening to it on vinyl anyway and we know whatever they used will be a relief compared to the various, sometimes absurd, and usually terrible stereo versions.

“I had probably five lengthy conversations with [Apple Records’] Neil Aspinall over the last ten years of his life. In every one I begged him to put out the original configurations in the original mono. At first, he couldn’t quite understand why I was so passionate about it.

“By the third conversation he realized I was never going to stop bugging him about it and started seriously considering, not if, but when it could get done. He always had one distraction after the other, the Las Vegas thing [LOVE] took a lot of his time, but I’m sure he put it in motion before he left us. Anyway, I’m very glad it got done.”

During 1974 as a music journalist, I attended a press conference in Beverly Hills at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel when George Harrison was announcing his first US solo tour. His remarks were published in the November 2, 1974, issue of Melody Maker.

On meeting the Beatles, Harrison said, “Biggest break in my career was getting into the Beatles. In retrospect, biggest break since then was getting out of them.”

Was he amazed about how much the Beatles still mean to people?

“Not really. I mean, it’s nice. I realize the Beatles did fill a space in the Sixties. All the people the Beatles meant something to have grown up. It’s like anything you grow up with—you get attached to things.

“I understand the Beatles in many ways did nice things, and it’s appreciated that people still like them. They want to hold on to something. People are afraid of change. You can’t live in the past.”

I first met Sir George Martin at The Hollywood Bowl in 1996. He had sent me a note in the mail after hearing a recording I produced, praised my work, and invited me to the soundcheck at the legendary venue when he prepared a tribute event that showcased the repertoire of the Beatles.

I spoke to Martin again in 2006 at Capitol Records Studio B. It was at a playback party for the Beatles’ LOVE.

George talked about a Frank Sinatra recording session he saw in this same room on his first visit to Hollywood in 1958.

The British EMI label sent him over the Atlantic after Martin was invited by Capitol label executive Voyle Gilmore to visit the American division. Martin described that ’58 booking when Frank Sinatra was backed by Billy May’s orchestra while actress Lauren Bacall was in attendance. The songs were eventually placed on Sinatra’s Come Fly With Me LP.

We chatted for a few minutes and I thanked Martin for discovering and signing the Beatles to their British record label deal. I complimented his persistent determination, along with Brian Epstein, in prodding Capitol Records to have faith in Martin’s groundbreaking Parlophone/EMI recordings with the boys in 1963.

One of Martin’s productions by the Beatles started playing in the studio.

Try hearing their sound over custom TAD monitors inside Capitol Records…George autographed an album, put his arm around me and smiled, “Pretty good stuff. Don’t you think?”

(Harvey Kubernik is the author of 20 books, including 2009’s Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon, 2014’s Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972, 2015’s Every Body Knows: Leonard Cohen, 2016’s Heart of Gold Neil Young and 2017’s 1967: A Complete Rock Music History of the Summer of Love. Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. In 2021 the duo wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s Docs That Rock, Music That Matters. His Screen Gems: (Pop Music Documentaries and Rock ‘n’ Roll TV Scenes) is scheduled for December 2025 publication.

Harvey wrote the liner notes to CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, The Essential Carole King, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special, The Ramones’ End of the Century and Big Brother & the Holding Company Captured Live at The Monterey International Pop Festival.

During 2006 Kubernik appeared at the special hearings by The Library of Congress in Hollywood, California, discussing archiving practices and audiotape preservation. In 2017 he lectured at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio, in their Distinguished Speakers Series. Amidst 2023, Harvey spoke at The Grammy Museum in Los Angeles discussing director Martin Scorsese’s The Last Waltz music documentary.

Kubernik is in a documentary, The Sound of Protest now airing on the Apple TVOD TV broadcasting service. https://tv.apple.com › us › movie › the-sound-of-protest. Director Siobhan Logue’s endeavor features Smokey Robinson, Hozier, Skin (Skunk Anansie), Two-Tone’s Jerry Dammers, Angélique Kidjo, Holly Johnson, David McAlmont, Rhiannon Giddens, and more.

Harvey is interviewed along with Iggy Pop, Bruce Johnston, Johnny Echols, the Bangles’ Susanna Hoffs and Victoria Peterson, and the founding members of the Seeds in director Neil Norman’s documentary The Seeds – The Seeds: Pushin’ Too Hard now streaming on Vimeo. In November 2025, a DVD/Blu-ray with bonus footage of the documentary will be released via the GNP Crescendo Company.

The New York City Department of Education in 2025 published the social studies textbook Hidden Voices: Jewish Americans in United States History. Kubernik’s 1976 interview with music promoter Bill Graham on the Best Classic Bands website Bill Graham Interview on the Rock ’n’ Roll Revolution, 1976, is included).