By Harvey Kubernik c 2015

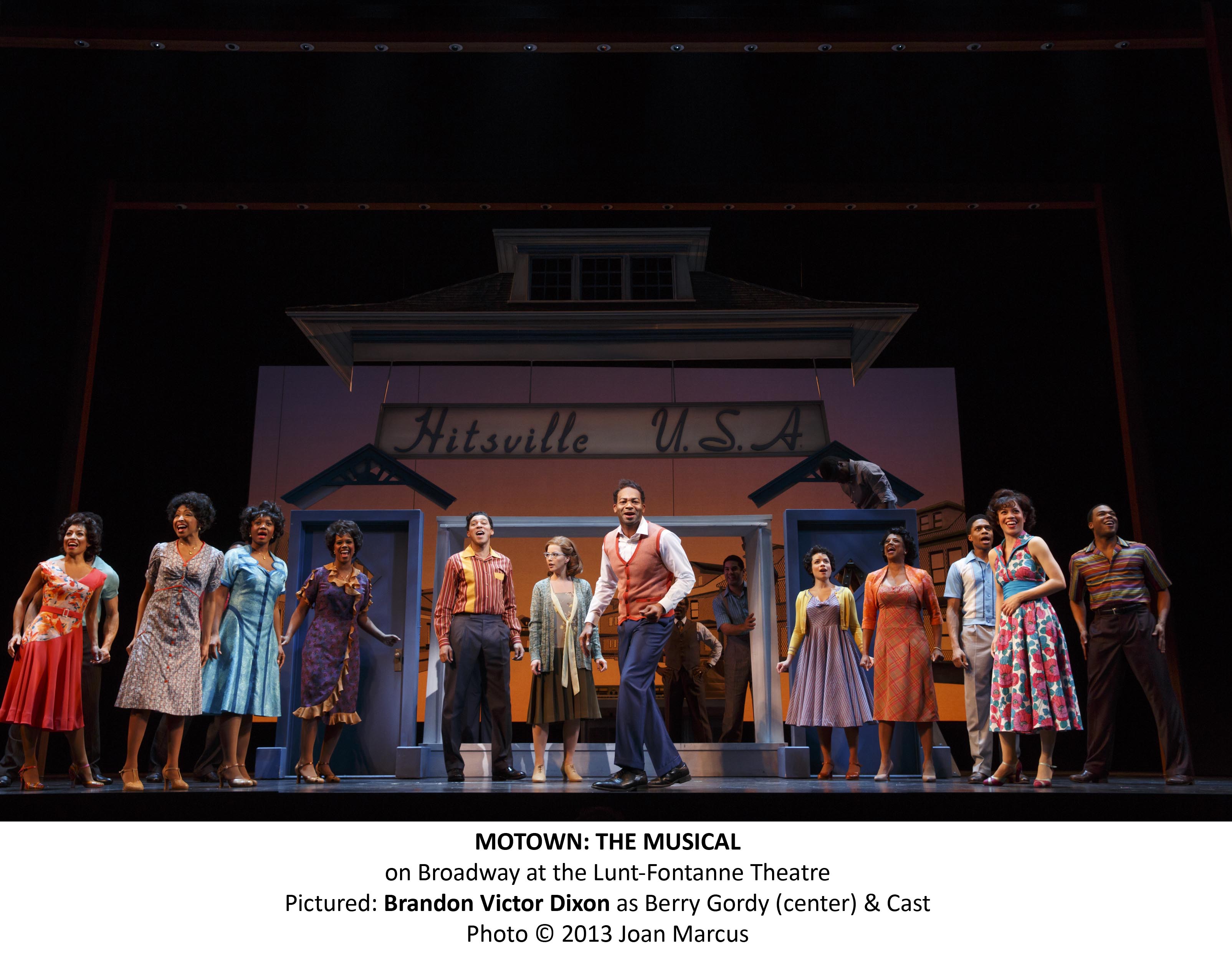

Producers Kevin McCollum, Doug Morris, Berry Gordy and the Nederlander Organization are staging MOTOWN THE MUSICAL for a six-week engagement through Sunday, June 7, 2015.

Tickets are now on sale and available for purchase at www.HollywoodPantages.com or www.Ticketmaster.com, by phone at 800-982-2787, and at the Hollywood Pantages Box Office (6233 Hollywood Boulevard). The box office opens daily at 10am except for Holidays.

MOTOWN THE MUSICAL concluded its Broadway run as both a critical and audience favorite and a commercial hit, having recouped its $18 million investment at the end of 2014.

Most recently, the First National Tour recouped its $8.5 million dollar capitalization cost in less than ten months on the road.

A UK production is slated for Spring 2016 and a return to Broadway for Summer 2016.

The play is directed by Charles Randolph-Wright.

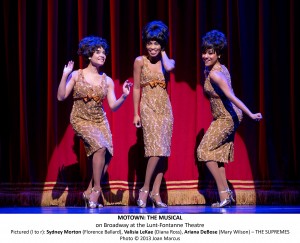

MOTOWN THE MUSICAL is the true American dream story of Motown founder Berry Gordy’s journey from featherweight boxer to the heavyweight music mogul who launched the careers of Diana Ross, Michael Jackson, Stevie Wonder, Smokey Robinson, Marvin Gaye and so many more.

Julius Thomas III and Allison Semmes star in the leading roles of Berry Gordy and Diana Ross. Jesse Nager portrays Smokey Robinson and Jarran Muse channels Marvin Gaye. Leon Outlaw, Jr. and Reed L. Shannon are Berry Gordy’s boyhood counterpart and the roles of young stars Michael Jackson and Stevie Wonder.

MOTOWN THE MUSICAL’s arrangements and orchestrations are by Grammy and Tony Award® nominee Ethan Popp (Rock of Ages), who also serves as music supervisor in reproducing the classic “Sound of Young America,” with co-orchestrations and additional arrangements by Tony Award®nominee Bryan Crook (“Smash”) and dance arrangements by Zane Mark (Dirty Rotten Scoundrels).

MOTOWN THE MUSICAL is produced by producer Kevin McCollum (Rent, In the Heights, Avenue Q), Chairman and CEO of SONY Music Entertainment Doug Morris and Motown founder Berry Gordy.

The performance schedule for MOTOWN THE MUSICAL is Tuesday through Friday at 8pm, Saturday at 2pm & 8pm, and Sunday at 1pm & 6:30pm.

For more information on MOTOWNTHE MUSICAL, visit www.MotownTheMusical.com.

For tickets or more information about the Los Angeles engagement of MOTOWN THE MUSICAL, please visit the official website for Hollywood Pantages Theatre: www.HollywoodPantages.com/Motown.

For tickets or more information about the Los Angeles engagement of MOTOWN THE MUSICAL, please visit the official website for Hollywood Pantages Theatre: www.HollywoodPantages.com/Motown.

Berry Gordy, Jr. was born November 28, 1929, in Detroit, Michigan. A former boxer and assembly line worker, and veteran of the Korean War, Gordy, in 1955, ran a jazz record store, his first venture into the music business. Although the shop failed, he didn’t give up.

Gordy wrote songs, and got his first action when vocalist Jackie Wilson cut some of his tunes, including “Reet Petite,” “That’s Why (I Love You So),” and “Lonely Teardrops.”

Gordy’s sisters Anna and Gwen, along with Billy Davis, formed the Anna label, which scored a major success with Barrett Strong’s “Money (That’s What I Want)” in early 1959. Berry, who was involved with the Anna label, then launched the Tamla label.

By the very late ‘60s, Gordy relocated the Motown operation, at this time, the largest black-owned corporation in the country, to Los Angeles, California.

Gordy eventually withdrew from the day-to-day operations, and in 1988, he sold his brainchild to a major corporation, MCA. The Motown empire shifted ownership to the PolyGram group of companies, now called Universal Music.

In 1994, Warner Books published Berry Gordy’s autobiography, To Be Loved. The book’s title is taken from a song Gordy penned for “Mr. Excitement,” Jackie Wilson.

I remembered a letter Berry Gordy sent to Kim Fowley in 1960 that used to hang in Kim’s Hollywood office as well as being displayed on kimfowley.net.

Fowley was Motown’s first west coast promo man for a month in 1960, handling several records, including The Miracles “Way Over There,” their single after “Bad Girl,” and just before “Shop Around” went top ten.

In 1960, Fowley had just co-produced and co-published “Alley Oop” by The Hollywood Argyles, a big hit record, and was doing six months active duty in the Air Force National Guard, while waiting for his royalty statement from the national “Alley Oop” chart placement.

“I was also working five records a week as a promo man after working for DJ Alan Freed ,” Fowley recalled, “and making $250.00 a week in U.S. dollars. I got the Motown job after seeing their ad in Cash Box. Berry Gordy’s sister Loucye took my phone call in Detroit that I placed from Happy’s Gas Station on Hollywood Boulevard, which I also used as an office. She was gracious, focused, heard my spiel about how I could help the label out in California. Berry then got on the line, we talked about singer Marv Johnson who he just cut, and he quickly sent me a letter with a check. You could be on the street then, based out of a gas station, and get a label head on the phone in those days.”

Kim Fowley had nothing but admiration for Berry Gordy’s contributions to the music business and his impact on our lives.

“Berry Gordy. Pioneer, military strategist, musical genius and business icon. The role model of every record company that followed him,” Fowley offered. “What he did, and the talented artists, musicians, songwriters and producers he helped bring forward, especially in the 1957-1960 pre-Martin Luther King, Jr. emerging from Selma Alabama period was heroic. An impossible fantasy,” he concluded.

During 1960, Russ Regan, disenchanted with performing, switched from being an artist to promoting records. Russ was recruited by Motown Records and became integral in establishing what we know today as the “Motown Sound.”

“The first record I promoted was ‘Please Mr. Postman’ by the Marvelettes in 1961,” stressed Regan, whose monumental record career included stints as President of MCA/UNI Records, and 20th Century Records as well as an executive shift for Gordy’s Jobete Music Publishing Company.

“I also worked with the Supremes, Smokey Robinson & the Miracles, and Marvin Gaye. Believe it or not, Marvin Gaye had moments of greatness on stage or he could be lousy. And I’ll tell you why. He really didn’t like performing. It was a job to him. It can’t be a job for a performer. People don’t realize this. You can’t be up there thinking you are working.

“Barry Gordy, Jr. used to come to town. He taught me about hooks in songs. And that people buy records because they have to love them, not like them. There used to be record hops at high schools. One time at Jefferson High school I took Marvin Gaye in Watts. He had never been out there before. The girls attacked him. He lost one shoe of his penny loafers. We went to Fairfax High School. Groups played in the auditorium.

“People like to discover things. The Bahiri Brothers would go into Mississippi with wire recorders and record talent. Barry Gordy offered me a job but I didn’t want to move to Detroit. I’m a California guy. And I was taught a lot about the record business by Berry Gordy, Jr. I became a promotion man three years 1961-1964. I learned the value of a song. And the hooks of a song. Every Motown hit has hooks in it. It starts with the opening. You can always smell the opening of a Motown record.”

In 1994 I interviewed Berry Gordy at his Bel-Air, California home for HITS, BAM and Goldmine magazines. Portions of our conversation appear below.

HK: Motown began with 45 records. Then the album format, eventually 8-track tapes, cassettes and now compact discs. Were you personally impacted by the growth of the LP market?

BG: Now very much. We were about producing songs that were great. And so a lot of the producers who would be coming to our Friday morning  meetings, they would say when the song wasn’t that great. “Oh, that’s an album tune. That’s just going on the album.” I’d say, “No. No. There are no album tunes. Every tune has to stand on its own.” We didn’t look at album tunes as such. We would pick tunes that were hits and that’s why they would go on albums and pull out a hit here, a hit there, you know? So it didn’t impact us that there were albums and we had departments and all that stuff. But as far as recording, unless there was a concept album and things like that, we would say there are no album tunes. We’d say that all the time.

meetings, they would say when the song wasn’t that great. “Oh, that’s an album tune. That’s just going on the album.” I’d say, “No. No. There are no album tunes. Every tune has to stand on its own.” We didn’t look at album tunes as such. We would pick tunes that were hits and that’s why they would go on albums and pull out a hit here, a hit there, you know? So it didn’t impact us that there were albums and we had departments and all that stuff. But as far as recording, unless there was a concept album and things like that, we would say there are no album tunes. We’d say that all the time.

HK: What about compact discs?

BG: They were cleaner. When we were first told about them we couldn’t get them. I mean, no one was manufacturing them, you’d have to wait, and it was a problem. And the cost was just incredible and you had to order so many before you even got them. We were just a small company and the CD manufacturers, and all these new things, were things that confused us more than anything else. Because we were about hit records and one record at a time, and different producers were doing different things, so I don’t know a lot about how they affected me emotionally or stuff like that.

Actually, we made money on every new format that came out because it was a new configuration. So they’d buy all over again, whatever it was. Then you have software, that’s what it is now. That’s why Jobete is so important to us, because of the songs and its software. Whatever it is, a great song is a great song. That’s all it is. And whatever configuration comes, we don’t worry about the configuration. We worry about if we have the product. And that’s what we’re doing going into Jobete saying, “Hey, before we do anything else, let’s make sure we have great songs. Make sure these songs are still great. Let’s look at all the other 95 per cent of our songs.”

‘Cause there’s great songs that were great but they were produced wrong, or maybe the wrong singer, or maybe this or maybe that. But the quality is still there. So let’s look at all that. So that’s what we’re doing now and that’s fun. Because I started as a songwriter. I love songs, so you know, that’s a hobby.

HK: I know England and Europe have always been behind the Motown Sound. They have the Tamla-Motown Appreciation Society over there. Before your first major EMI distribution deal for the product line. England always has had a strong relationship with your music. In “To Be Loved” you acknowledged that fans in the U.K. knew the groups, the writers and the producers.

BG: As far as the U.K. is concerned, it is very, very special to me. Because, actually, we were, I think, more popular there than we were in our own country, you know, for a long time, it seemed. I think the appreciation was different. They were not blasé about our music early on. Way back, the pirate ships and all that stuff, they discovered the sound and they were always very important to me when I’d go over there.

They were just together. I loved their creativity with what they did with our album covers and how they just did it. And when we first went over there with the fan clubs, and the signs and stuff that they had for us. So the U.K. has always been special for Tamla-Motown.

HK: You had some sort of loose early distribution deal with another company, Oriole Records, before EMI handled the distribution. How did that happen?

BG: I don’t really remember for sure how the Oriole Records deal happened. My attorneys, George Schiffer and Ester Edwards, and Barney Ales put it together. I was really busy creating, producing, working with writers and stuff like that, and that’s what I say in the book. There’s a lot of those unsung heroes that set up things for me. I could take credit for being mainly responsible for the product but a lot of these deals and things were started with people at Oriole.

HK: And even years later, in England, Motown issued “Tears Of A Clown” by Smokey Robinson and The Miracles, a couple of years after it was initially cut as an album track and it charted there.

BG: It went to number one in England, I believe, and we hadn’t even released it here, or something like that (laughs). They were on top of everything.

And when The Beatles Second Album had three of our songs (“Money{That’s What I Want},” “You’ve Really Got A Hold On Me,” and “Please Mr. Postman”), it just indicated to us that they obviously had been listening to our music and they were aware of it, enjoying it and loving it. It’s always been very important to me.

HK: I really enjoyed the story in the book about your negotiation with someone representing the Beatles and the three Jobete copyrights that were to be included on that Beatles album. You had met Brian Epstein before that when he visited Hitsville in Detroit. The Beatles’ representative was seeking a reduced rate for the three tunes on the Beatles’ album. I initially thought the dealing was racist, but it wasn’t.

BG: I think there was some guy there doing his job, trying to get rates on whatever they were doing. They were doing more than one song. If it had been one song, I could say to them, “You’re doing one song.” But, “You’re doing three songs,” on The Beatles Second Album, and it’s negotiating, like when you go to the supermarket and you buy more than one thing, you get a deal. So I thought it was business and I say it in the book. I never jump on issues as racial unless they really are. Somebody was doing their job on behalf of the Beatles.

HK: Did you, or do you, every chuckle when those songs shipped millions of units and became part of the Beatles live show?

BG: Sure I chuckle, even today. I say it in there (the book). It’s funny and if I had to do it all over again (accept a discount rate in the three Jobete copyrights) I would make the same decision. It’s better to have a part of something than all of nothing.

HK: I was fascinated by the anecdote in your book about a record distributor you met early in your career when you had a record store that carried jazz, “ The Mad Russian.” You said in To Be Loved, “I didn’t know if it was possible to be a Russian and a Jew at the same time.” And earlier, you met “The Junkmen,” And you mentioned, “I later found out they were called Jews, the more I liked them. They liked me, too.” The Jewish community embraced you as a youth.

BG: With the junkmen, they sat down with me as a little kid in the neighborhood and they had wit, wisdom and told me some stuff for my own good. And the fact they owned most of our buildings around us, I thought they were brilliant. And I said, “I want to learn what they are doing.” They taught me about supply and demand! And, that’s what the book is supposed to do for inner city kids, to understand if they want to build something like Motown, see, it’s not built by devious means, the Mafia, cheating artists out of their stuff. It was built by just what you’re saying. And you explain it almost better than I do. You understand it very well.

HK: It seems to me, that when you were watching legendary record people in the studio like George Goldner (of Red Bird Records) or The Chess Brothers (of Chess Records), you didn’t think, “That’s a Jewish guy.” You have always had a philosophy that if the person can deliver, you worked with them, and there wasn’t any sort of religious division or racial tension that sometimes exists today.

BG: There was no division at all. If a person was a bigot than that was where the division started.

It wasn’t even a matter of black and white. They were businessmen, and black artists had a sound they looked for if white artists had the same sound. In fact, many white artists were on their labels, all the songs Dick Clark was playing. So it wasn’t a matter of black and white, see. It was a matter of the artist that had the sound that was happening in that time. And George Goldner I did notice was a white man.

HK: George Goldner gave you a hundred dollar bill after you talked to him in the lobby of United Sound Studios. “It’s like a down payment in case we ever do any business together.” People just wanted to get some good tunes out. It didn’t have so much other stigma to it.

BG: And that’s what happens. Life is not nearly as complicated as people make it. See, it’s basic. We got to get back to basic values and basic communication. Two and two is four. And all people want the same things, I constantly say. Each one of us is different though, and I tell artists to bring out their own uniqueness. That’s why you’ll get a Stevie Wonder, a Marvin Gaye, a Smokey Robinson. You’ve got to nurture that. That’s what we try to do. Nurture their difference.

And so it wasn’t me that was the genius. If I was a genius of anything, it was bringing out the genius of others, because if they reach their potential then I had felt that maybe I could reach mine. So in bringing out the genius in others and finding it, sure, it was hard and tough, but your clues will tell you. And then, stopping them from focusing on other things other than what they’re doing.

And there’s still 99 percent of the people, in my opinion, running around there now with this great talent, great art, great ideas like that, but they will never make it through. The idea is that when you make it through the fame, fortune and riches and power, and you are not the same person you are when you started out, then you have been a failure. I don’t care how much money you got, fame or fortune you got. You got to be the same person that you started out with. And when you are then you can consider yourself a success.

HK: What was your first impression of Smokey Robinson?

BG: Well, Smokey Robinson, my first impression was he was great, a great poet, but he didn’t know how to really write songs, or put songs together. When he learned how to put stuff together and he really understood, Smokey was incredible. When I turned down his first 100 songs, he got more excited with every song. I said, “This guy has to be either crazy or one of the most special people I’ll ever meet.” He was incredible. He turned out to be one of the most special people I ever met.

HK: And with an angelic voice

BG: Oh, yes. Pure. And then, he got it and understood it. So now Smokey has succeeded at the cycle of success. It takes a lot of character, because you are tempted along the way. The cycle of success is a vicious cycle. It takes you into places. People offer you things never offered before. To succeed and be successful is tough so it takes a lot of character. You got to keep your same values. So Smokey has done that. The Four Tops have done that. And most of the Motown artists have it drilled into them and they were all very tight.

HK: The Four Tops?

BG: The epitome of loyalty, integrity, class. They’ve been together for 40 years, the same four members. That is unheard of, impossible, and I just admire them so much. I admire them the most of any of the artists.

HK: The Temptations?

BG: Legends. They’ve managed to keep their look and their style all these years and they’ve changed members constantly, but Otis and Melvin have done just an amazing job of finding one major talent after another. Because they are legends, people want to be with the Temptations, and they have proven that the group is stronger than any of its parts. I don’t care how great that part was, the Temptations are an institution.

HK: Diana Ross?

BG: Diana…Special, magic, sensitive. When she does a song like “Somewhere” in front of an audience she still cries, I mean, I’ve never seen her do “Somewhere” without crying. In fact, we used to stop her from doing it every night in the week. The Bernstein song from “West Side Story.” She was so dramatic and then she did the second ending and it was too much emotionally. She’s so emotional and she gives all to her audience and she is sincere about it and serious about it.

HK: Marvin Gaye?

BG: The truest artist I’ve ever known. Whatever he was going through in his life he put on records. So if you want to know Marvin just listen to one of his records.

HK: Stevie Wonder?

BG: Innovative. The most innovative person that I’ve ever known. But also unique with his tones and his voice quality and all that. He was as close to genius, and I don’t like to use the word genius, you know. Marvin could have been a genius. I don’t like to throw it around, but Stevie is one of those kind of special, special, special people that had a sound, and he’s quick. He’s creative and he can make up something very quick.

HK: And he is involved in technological developments.

BG: That’s what I’m saying. Contraptions. He would take technology. He was the first in technology. He’s an innovator.

HK: Michael Jackson?

BG: Greatest entertainer in the world and one of the smartest people and businessmen in the world. He conducted his own career, basically. He knew what he wanted. And from nine years old he was a thinker. And I called him “Little Spongy,” because he was like a sponge and he learned from everybody.

He not only studied me, but he studied James Brown, Jackie Wilson, Marcel Marceau, Fred Astaire…Walt Disney. And he bought the Beatles’ catalog. Michael is nobody’s fool. Very bright. Very smart.

HK: The Holland, Dozier and Holland production and songwriting team?

BG: H-D-H was phenomenal. They came up with hit after hit. They started a thing. They had a lock on the Supremes and they took them, and did stuff on Marvin. H-D-H was absolutely brilliant. The three of them were different and they all complemented each other.

Eddie (Holland) did mostly vocals, Brian (Holland), I thought was the most talented, creative person. He was my protégé for many years. I thought Lamont(Dozier) was also a good writer, and he was good on backgrounds and this and that and so forth. But Brian would do something like he would play and sing and create something and all he would give ‘em was, like, “sugar pie honey bunch,” and pass it on. So they had their own assembly line. And they were tremendous.

HK: The producer and songwriter, Norman Whitfield?

BG: Norman to me was probably the most underrated of all the producers, because he was producing by himself. And he would deal with different sounds, different beats, change with the times and write his stuff, and also Barrett Strong would work with him as a writer on many of his things. Norman was innovative and he had fire. And he had a different kind of style. His beat was different and could go from “Cloud Nine,” “Psychedelic Shack,” “papa Was A Rolling Stone,” to “Just My Imagination.” He was sensitive and I think he could do so many different types of things. Then he’d come right back with “War” and then “Ain’t Too Proud To Beg.”

He could take one chord, like on “Papa Was A Rolling Stone,” and play the same chord and do all these different beautiful melodies and things that many people could not really imagine this guy doin’. And I would watch him and he did it all by himself as a producer. He would work with five guys in the Temps and he would change leads on each one. He would pick the right lead for the right song, ya know, and he’d utilize all five of those leads in a song that was just incredible.

When I listen to ‘em today, now that I have time to listen to ‘em, I’m saying, “Wow! This guy was probably the most underrated producer we had.”

HK: Jackie Wilson. People are rediscovering Jackie due to some of the repackages.

BG: The most natural artist I’ve ever seen in terms of dancing, vocals. His voice was the strongest. He could do opera, he could do rock, he could do blues and he created the most creative singer that I’d known As I said in the book, he never sang a bad note. Maybe a bad song, but never a bad note…one of the most talented artists I’ve ever seen. ‘Cause I’m talking about all great people here. So when I say talented in another way, I mean he was the most natural.

HK: Was he more dynamic live than on record?

BG: Yes, of course! He was more dynamic live than on record. And he could dance, and could do flips and splits. Different than Michael. Michael studied a lot of people who did a lot of things. Jackie did not study anybody but Jackie. Jackie was Jackie, the most natural, innate performer, probably, that I’ve ever seen. He had nobody to study that I know of. Jackie was an original. Probably the most original artist that I’ve ever seen.

And he should be rediscovered. Because he created stuff and he could wink on cue. I said it in the book. He could do things, do a spin, and then wink at the girls.