By Harvey Kubernik Copyright 2025

I revisited the work of Moby Grape in 2025.

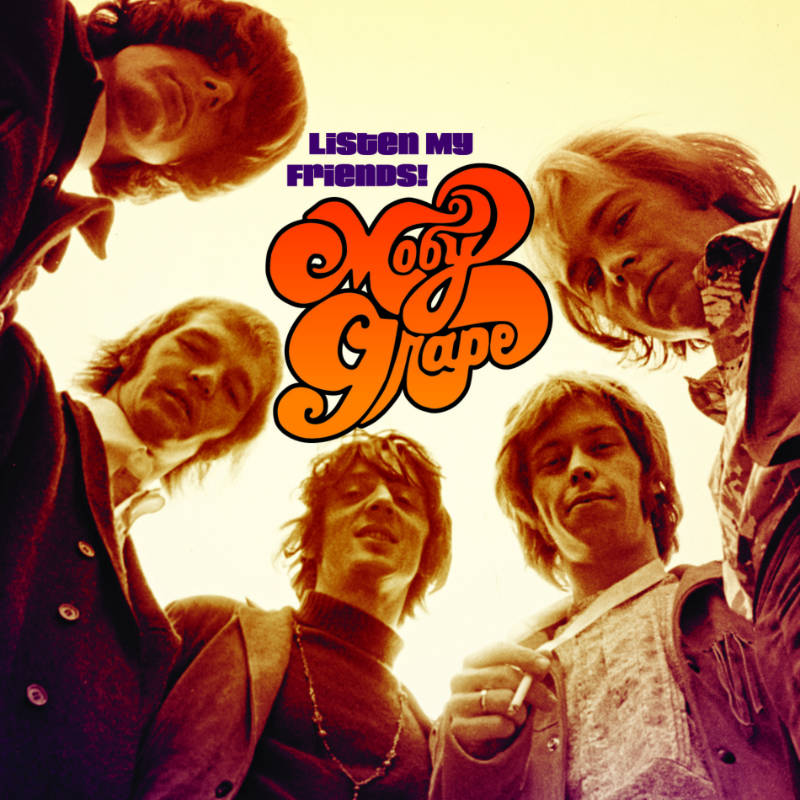

During 2007, Columbia/Legacy Records released Listen My Friends! The Best of Moby Grape, which marked the 40th anniversary of their debut album release on Columbia Records. The original lineup was Skip Spence (guitar), Peter Lewis (guitar), Jerry Miller (guitar), Bob Mosely (bass), and Don Stevenson (drums).

Much has been made of the tragic story of Moby Grape…and it’s all true. Management problems, record company decisions, disputes over name ownership, confusing touring scenarios, madness and a whole lot more. But what remains is the memorable music. Although the band’s recorded catalogue is fairly slim, what exists is terrific and essential to possess.

The Grape, although heralded as part of “The San Francisco Sound” (whatever that was) was a mixture of Los Angeles, San Diego, San Francisco and Seattle musicians.

Basically, built around Skip Spence, (original Jefferson Airplane drummer and songwriter of “My Best Friend” and “Blues From An Airplane,”) who was returning to guitar – his main instrument. Peter Lewis, a child of Hollywood (son of actress Loretta Young and television producer Thomas Lewis), an excellent guitarist and songwriter in his own right, was a refugee of various L.A. bands, including his own group, Peter and The Wolves.

Peter Lewis photo by Heather Harris.

The third guitarist, Jerry Miller, was a veteran of the hard-boiled Pacific Northwest bar band scene, who cut his teeth playing briefly with Bobby Fuller in the El Paso area, and constantly ran in the same Seattle circuit as Jimi Hendrix. Miller came as a team with drummer/singer Don Stevenson, both having been members of the Seattle-based Frantics. The final member was Bob Mosley, a positively bad-ass bassist and blue-eyed soul shouter, who came to L.A. from San Diego, and had been part of an early “supergroup” with Lee Michaels, Joel Scott Hill and Johnny Barbata.

“From the very first time the five Grape members played together in winter 1966 in San Francisco at a church basement rented by then manager Matthew Katz, there was undeniable chemistry,” stated author Matthew Greenwald, a Moby Grape chronicler.

“Spence’s chunky rhythm guitar meshed perfectly with Lewis’ Jim McGuinn-inspired finger picking playing. Over the top, Miller was free to add fluid, Michael Bloomfield-inspired lead lines that glued everything together. The rhythm section of Mosley and Stevenson was funkier than anything that came from San Francisco, rivaling the Stax-inspired bottom end of Buffalo Springfield. Like the Springfield, Moby Grape featured multiple singer/songwriters…all the members, in fact, could have fronted their own respective bands.”

In 2007 I conducted interviews with four of the original Moby Grape members. Spence had passed. Miller died in 2024.

“When we first began, we could all sing and we could all play and we were just ready to collaborate with each other to create what I think is good music which is gonna last no matter what,” explained Don Stevenson.

“There was magic when we played together the first time. It was immediate. It was Mosely who told Peter about Jerry and I. That was the end of the auditions. There was no more. I don’t know if they auditioned anyone before us. When we got together and played the first time it was over.

‘God. This is like so much fun!’ And when we played constantly at The Ark, an after-hours club, and people would come over after the Fillmore or Avalon, including Lee Michaels, Buffalo Springfield, Janis Joplin. I’d look out there and it looked like an audience of water buffalo. It was just amazing. So, it was a great format to develop our material. We didn’t think about influencing anyone but we thought about playing our music. I went from bars and after-hours clubs in Seattle to the Philadelphia Spectrum, shows with Jeff Beck, and television programs like Mike Douglas.”

During 1967 Moby Grape landed a residency in a Sausalito (San Francisco area) club named The Ark. Devoted fans and other musicians like Jerry Garcia, Big Brother and the Holding Company and Buffalo Springfield’s Stephen Stills and Neil Young monitored and applauded Moby Grape on the bandstand. In the first part of 1967 amidst record-label frenzy David Rubinson of Columbia Records signed the band and eventually produced their debut disc in Hollywood.

“It came together quick because we had all come from different musical endeavors and we hot and ready to go,” described Bob Mosely.

“Don Stevenson could introduce shuffles and we stuck it off being a bass player and a drummer working together. We worked around how to play with something brand new. Jerry Miller was a fantastic R&B guitar player who could also play jazz. He played honky-tonk for me one time. Peter Lewis was a finger picker. Skippy had an aura about him the way he wrote and recorded his songs. He would dump and ping-pong tracks and get into generations of different music. He was really good at that. Skippy was a dynamo on stage. He’d spin, circle and jump with his guitar on, sing his parts and play and wail.”

“What I loved about Skip was that he would play guitar like a drummer,” added Stevenson.

“He was a drummer. He would jut play rhythms and not on two and four. Rhythms that played around inside the patterns. And he was very ethereal. You would think it would be very difficult to have three guitars but Skip always wound his way in and out of picking and lead guitar and wound his way inside of everything that created this great tapestry. He was brilliant. Honest to God, he could have been Bob Dylan. He had that kind of insight, that kind of an edge, he didn’t see things the same way that you and I might. Skippy perceptually and conceptually was brilliant.”

Mosley had strong soul music roots. Songs such as “Come In The Morning” and “Bitter Wind” are classics of their kind, and remain timeless. The Miller/Stevenson team also had a strong soul and pop foundation.

The Don Stevenson/Jerry Miller songwriting team was responsible for some of the loudest and tightest pop rock recorded in the sixties. The duo penned “Hey Grandma,” “8:05” and “Murder In My Heart For The Judge” among other items.

Listen My Friends! nicely encapsulates the bands’ recorded legacy. Half the group’s self-titled debut is included here. Some of the standouts are the afore-mentioned “Omaha” and “Sitting By The Window.” “8:05,” has aged particularly well, and sounds almost like a prototype for Crosby, Stills & Nash. Probably due to space limitations, a couple of glaring omissions are Lewis’ “Fall On You” and Mosley’s “Come In The Morning.” But the tracks remain crisp and fresh, and David Rubinson’s production should be noted here, as he brought out the band’s rage and live energy in the studio with great style.

“Jerry is probably one of the greatest guitar players ever,” Stevenson stressed.

“He is just dedicated. He’s a regular blue collar guitar player. When you’re in your bliss doors open up and things happen. And it impacted me as a drummer. I played with Jerry for a long time before Moby Grape. What was really cool about the Moby Grape was that we got to create our own music. When you find someone great like Jerry.

‘“Hey Grandma’ was kind of made up about those young ladies in those Granny dresses back then wearing patchouli oil back then and they were inspirational. That’s where the song came from. We would come up with the lyrics together and play together.

‘“8:05’ we crossed the San Francisco Golden Gate Bridge at 8:05. That’s how that song came about. ‘Murder In My Heart For The Judge’ happened when I was called to go to court for driving my vehicle with a suspended license. My tabs were outdated. On the date I went to court there was a young lady that had very a similar transgression to mine and he waived everything and she got to walk. And he fined me a hell of a lot of money. At that time the judge saw someone with “bizarre hair” and that’s what the judge saw in me and just tossed the book at me. I went home and wrote the song, brought it to Jerry, he wrote the chords for it.”

Peter Lewis, the poet of Moby Grape, suggested that the Moby Grape sound was “kind of like the Byrds with the blues.”

“That was part of it what I heard going out with me and Bob and then it all started evolving and Skippy was the one who was able to take what we had and make it sorta Moby Grape. He was the one who was able to arrange the songs to make them all sound like we were all in the same band. That was his genius. A great arranger and songwriter.

“The three-guitar lineup was fine as long as we were all helping each other. When we started stumbling over each over that was when things started getting bad. We had fire on stage and that’s why no one wanted to follow us. We just wanted to kick everybody’s ass. We were mad. They call it the summer of love. It wasn’t so much that the words were depressing or about darkness or anything, but the music just sounded a lot different. It was real aggressive. It sort of was a signal that things were changing in general,” admitted Lewis.

“Moby Grape was involved on this ride, not just about us, but the whole generation and not thinking about show business. We didn’t make political statements. We were just trying to document our experience with our songs. Trying to talk to each other through them. We felt like we were supposed to be examples of what it was like to be a cool hippie. We did find ourselves in that position.

“There was something about those bands from San Francisco that were supposed to be messianic in a way. You had all these people out there staring with these blank expressions on their face that is lot different from playing in the clubs where you are looking at guys in sharkskin suits with razor cut hair. And it’s a whole different deal. There was love and peace, and if you wanted to sorta act like that you could be like that. Whatever we were trying to do by the way it looked, as far as people dancing in circles, wearing flowers, being happy, but if people are gonna respond to you that way, fine, but you had this other part of the society that saw a dark side,” volunteered Peter.

“When we played live there was a bond and a chemistry with the audience,” offered Mosely.

“We did structured songs, not free-form jams, but three-minute versions with a couple of guitar solos and a few endings. We had a couple of songs that we stretched out on, ‘Dark Magic’ for example and out on the ending of ‘Hey Grandma.’

“The Ark was our laboratory. We had a built-in audience. When the first record was ready, we had ironed out our songs, rehearsed in L.A. for a couple of weeks and we were ready to go. Regarding our three-guitar lineup what was really cool is that Pete was a finger picker, who studied under Joe Maphis.

“I’m a blues be bop enthusiast. Peter played beautiful lines and Skippy played real solid chunky rhythms and he had other styles, but they both played that way in Moby Grape, so I had plenty of room. We ended up getting along just fine. Skippy’s solid rhythm was really strong. At the time we kept our songs short because we didn’t know you were allowed to do anything else! (laughs).

“At the Fillmore and Avalon in San Francisco we then realized the handcuffs were off and we could do anything. We started to stretch out and that’s what people liked. The experimental stuff and the harmonies. We rehearsed like crazy everyday. Getting those harmonies, sometimes counter point and a little five-part stuff.”

“We brought our musical skills and musical ideas and put them into a format like a straight-ahead song,” emphasized Stevenson.

“Being a drummer in a band with three guitarists I think made me more sensitive. If it’s a power trio you’re like a lead drummer. If it’s a traditional band you’ve got to worry about spaces as much. With the intricacy of three guitars, I think it made me a little more sensitive to the music. I always liked playing funky shuffles. But when you have one guy who is a finger picker (Lewis), Skippy would float in and out, and Jerry who could tear it up, you had this situation where you don’t want to get in the way of all that. And I kind of learned where you really have to consider the space rather than filling the space.”

The group’s connection with their friendly L.A. “rivals” Buffalo Springfield by far exceeded their three-guitar, multiple songwriting front line.

While the bands shared a residency at The Ark in San Francisco during the autumn of 1966, Lewis and Neil Young grew close, as did Stephen Stills and Mosley. As well, Stills later admitted to Lewis that their Top-ten hit, “For What It’s Worth” was a sort-of influenced by the Miller/Stevenson “Murder In My Heart For The Judge” (both had the same E-Major/A-major, folk-soul chord progression and shuffle), and an unreleased Lewis song, “Stop” (Stop! listen to the music’). Later, during the summer of 1967, both bands had houses in California at the Malibu Colony, and spent time jamming and exchanging musical ideas.

“Buffalo Springfield did hear us play ‘Stop!’ and ‘Murder In My Heart’ at the Ark,” recollected Lewis.

“Later after they came back to San Francisco and played the Avalon Ballroom, Stephen said to me, ‘You know, we just recorded this song (For What It’s Worth) and after it was done, you know, I flashed on where it came from.’ I said, ‘who cares? ‘It was cool. There was nothing to get into litigation about, man.

“We lived in Mill Valley. I had a great time with Neil and Stephen in Bob Mosley’s apartment playing each other songs. Bob wasn’t married and you could go over to his place. Somebody had some pot. It wasn’t very good in those days. All bunk. Like powder.

“At some point, we’d see Buffalo Springfield. We’d see them in passing or at an airport. There was sort of a thing where they made it, ‘cause they had their hit records and we didn’t. There was a point where they took us to meet (Ahmet) Ertegun down in L.A. It was like sitting down, cross-legged on the floor, and Ahmet smoked a joint and passed it around. What Neil and Stephen we’re trying to say, and I kind of knew this about show business, you better be able to call the guy that owns the company and get a call back.’ Columbia is not like that. Buffalo Springfield really wanted us to make it. That’s what I remember.

“They had Greene and Stone as managers. Everybody wanted to sign us. We signed with Columbia.

“Later, in 1967, my brother went to USC Film School. He was doing a TV show in the San Fernando Valley and Buffalo Springfield was taping a thing on the program. Herman’s Hermits were there. I was watching them do their segment. Neil came over and we were taking. He said ‘Do you want to come over and meet Peter Noone?’ I said ‘OK.’ We went into the dressing room. Neil is kind of taken with Peter Noone, which I thought was odd.

“But I know how big Herman’s Hermits and Gerry and the Pacemakers had been in Canada. Peter was smiling like he does. Like all the English people do. But Like Them, with a bottle of Vodka in a brown bag. They are kind of drunk. I remember playing with Them and Van Morrison. In those days you could take a bottle of liquor on an airplane. From the morning I met those guys, we played in Sam Francisco the night before and later went to the airport, Van was drinking all day. It didn’t affect him at all.

“Buffalo Springfield had a beach house in Malibu around 1967. Moby Grape had one in Malibu at the same time. We were renting Rod Steiger’s beach house. One day I remember Neil and Stephen walked in and they wanted to borrow this boat that Rod Steiger had. It was a dingy. This encapsulates their whole relationship. They wanted to grab this boat and go out and get it beyond the shore break. They both climb in there and then they spent a half an hour on who is going to get to row. And then here comes this wave and sinks the whole thing, you know. I don’t remember if the boat ever got recovered. Nobody from the band went out and got it. But today Neil Young is rowing the boat,” underscored Lewis.

“In 1967 at the Monterey International Pop Festival, it was the first time I had seen Jimi Hendrix since a few years earlier when we used to watch together a lot of the touring bands who would visit the Seattle area,” recalled Jerry Miller.

“All the guitar players would show up then at the Spanish Castle, the Tiki or Birdland. Myself, Jimi and Larry Coryell we would all go. There was a guy we would check out, Jerry Allen, who was funky to a rat. He’d get up there with his Stratocaster guitar and arch his ass out. Man, he was the funkiest. We saw the Wailers, too. Later, after he was established, Jimi wrote a song “Spanish Castle Magic.” It was a venue in Midland, right between Seattle and Tacoma.

“Once time we saw Gene Vincent. We saw Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, and Little Richard. Chuck Berry was unbelievable. Chuck opened the show for Ray Charles, La Vern Baker, Frankie Lyman and the Teenager in 1957. I even took a date with me. I was 12. When Chuck came out and hit the opening notes to “School Days” I knew “this was it!” Everyone went to these gigs in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s because if you wanted to be a guitar player you had to. In 1952 I also saw Hank Williams. I was 7. My dad took me down there in a truck and we rode in the rain. I couldn’t be in the area where everyone was drinking and fighting.

“At the Monterey festival, I saw Jimi and Otis take over the show. I saw Jimi before his set, sitting in the music room, the dressing room, hanging out. Brian Jones the guitar player from the Rolling Stones was there. We chatted. He was all over the place. He was having fun. As a guitarist, I don’t think you can set things apart. Jimi’s set at Monterey was extremely right. Monterey was perfect. I was sitting right in front of Jimi at Monterey. It was wonderful, especially with a pipe coming from your right and a pipe coming from your left. Pretty soon you’re sitting there spinning. We sure had a good time. And Jimi got to see me too. We were both left-handed guitarists. Here we are a couple of schmucks from Seattle…

“In the movie Monterey Pop you get to see Jimi. What Jimi did was that he did the full chord thing. Anybody can play lead a hundred miles an hour. But to do a full package with a three piece, and have the P.A. and the lights. It was his day. It was beautiful. He had it. The sound was right, the color was right, and it was the chords. The Stratocaster and the Marshall amps. It came out with the full body flavor. The Marshall amps gave the bottom a nice hairy bottom and a full six-string blend with meat. The meat and potatoes. After his show at Monterey Jimi was signing girl’s breasts. They would pull up their sweaters, hand him a tube of lipstick, and he’d sign his autograph. I said to him, ‘That looks like a nice job,’ chuckled Jerry.

“Subsequently I saw him at the Whisky A Go Go in Hollywood when T-Bone Walker was gigging with John Lee Hooker and Jimmy Reed. I jammed with T-Bone and Jimmy Reed, and the people wanted Jimi to play, but they called out for ‘Purple Haze,’ and he didn’t want to do it again.”

“At Monterey we played a short early afternoon set but are not in the movie or soundtrack,” Peter Lewis recollected in our 2007 interview.

“That was another smart move by our manager Matthew Katz. [There was an argument or a dispute at the venue with the organizers]. So instead of a slot on Saturday night with Otis Redding, we were booked in an early slot on Friday when people were first arriving. There was nobody in the place. Our set went by real fast.

“I remember being backstage with Jimi Hendrix before he went on. It was great, he did what he did, all self- explanatory. The hippie black movement was not around until Jimi Hendrix. He showed up, the songs he sang, ‘Foxy Lady.’ He wasn’t singing ‘Old Man River.’ He did that and got everybody on that trip. He knew as long as they kept thinking about him on that level that he could turn into something like that. It reminded me more of voodoo. It was about music, and he could really play.

“There was a new frontier at Monterey, and a tremendous hope. It’s like some of the music you had the sense that the people who made it to that stage kinda knew something. Whatever they knew was like part of their music, whether they were expressing everything, literally or not. Only Bob Dylan was really doing that.

“Our debut album had just come out. We all went to a party thrown by Columbia Records head Goddard Lieberson. He had a turtleneck sweater and a little gold chain, with his hair combed down in front, and he didn’t have long hair. So, he was trying to look cool. And, he had a party at his hotel, and I remember jamming with Paul Simon for a while. Tons of people. Janis was there because they wanted to sign her. Janis Joplin couldn’t get arrested before Monterey. Her trip was, one day everyone is kicking your ass, and then the next day everyone is kissing it. It does something to you.”

Songwriter, multi-instrumentalist, arranger and record producer Chris Darrow of the Kaleidoscope painted a revealing memory of Moby Grape in performance when I interviewed him in 2007.

“In 1967, both Kaleidoscope and Moby Grape released their first albums. The Kaleidoscope’s Side Trips and Moby Grape’s first record set the standards for top quality California-based music of the period. Each is considered a classic today and, in my estimation, these two bands were the most musically adept bands to emerge in the psychedelic era.

“As a member of the Kaleidoscope, I had a chance to see Moby Grape play on a number of occasions. I also did a gig with them later on as a member of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. They were my favorite live band, besides us, in California at the time.

“With their triple guitar lineup of Peter Lewis, Skip Spence on rhythm guitars and, the greatly underrated, Jerry Miller on lead. Moby Grape had a powerful presence. Jerry used a classic, Gibson L-5, hollow body guitar, while most musicians of the time were playing Fender of Gibson solid bodies. The L-5 was mainly used by jazz players, not rock ‘n’ roll players. The great rock ‘n’ roll voice of Bob Mosley on bass and the steady pounding drums of Don Stevenson finished out the rock solid line-up. They were tight and loose at the same time. Very dynamic. Don Stevenson played so hard that they had to build a steel, cage-like apparatus for his drums to keep him from kicking them off the stage.”

“Our road manager constructed a set that looked more like a ‘Harley Hog.’ It was heavy duty,” detailed Don Stevenson.

“Everything on it was made for punishment. I had a set of Gretch that got stolen at the Fillmore and some people came in during the day and “moved our equipment.” So, these new drums were a natural wood grain set of Rogers and he set concocted himself how the hard ware worked with two serious posts coming out of either side of the bass drum that didn’t go to the floor, just out of the bass drum. Looked like a chopper. I’d use various sticks on slower songs.”

Moby Grape’s second album, Wow recorded in New York was a mixed affair. There were some strong songs, such as Lewis’ marvelous “He” (sounding not unlike something from Love’s Bryan MacLean) and the funky “Murder In My Heart For The Judge,” a Miller/Stevenson composition sung by Mosley. The album even housed a selection that could only be spun at 78 RPM as well as a “bonus” LP, “Grape Jam,” that included Michael Bloomfield and Al Kooper.

Spence started suffering from psychological problems and departed the Grape in 1968 subsequently waxing his only solo album, Oar. The foursome then rallied with Moby Grape ’69, a fairly cohesive album, with some real high points, such as Lewis’ sweet country-rocker, “If You Can’t Learn From My Mistakes.”

Also included is Spence’s swan song, “Seeing”. A monumental recording of the late 60’s, with dueling vocals and guitar lines, alternately shouting and intersecting with a palpable sense of power, magic…and madness. Mosely split the outfit in 1969 to begin a two-year stint in the Marines and the Grape continued as a trio, a couple of tracks from the last ‘official’ Grape album, produced by Bob Johnston, Truly Fine Citizen, round out the 2007 compilation. Lewis’ “Changes, Circles Spinning” (which was covered at the time by Joan Baez) is a lost gem.

Moby Grape helped Buffalo Springfield revise their musical direction, and influenced Led Zeppelin’s early recorded repertoire On Zeppelin’s “Since I’ve Been Loving You,” Plant & Co. actually reference Mosley’s opening line from “Never,” the opening track on Moby Grape’s Grape Jam LP. Plant who has touted Moby Grape in the media for decades is thanked in the credits by the band inside the Listen My Friends! album package.

Moby Grape’s sound on vinyl also connected with the Pretenders’ singer/songwriter Chrissie Hynde.

In an interview with me for Goldmine in 2004, Hynde mentioned her new songwriting collaborator, Tom Kelly, as someone who “had exactly the right sensibility of what I like. He kind of had this arrested development and he still plays like one of the guys on the first Moby Grape album. That’s how he plays, you know, like Bob Mosley or something.”

“We chose the name Moby Grape, and it became a self-fulfilling prophecy,” continued Peter Lewis.

“Wear a pea coat on an album cover with a white dickey and then they think Moby Dick. People end up putting you in a bag, especially in those days when everything was really new. Coming from a show business family, when you project this into the grid, people get into this feedback loop where you have at least, in the beginning, it becomes subconsciously who you are, and you end up naturally falling into this pre-conceived script in our case was that everybody started acting like those characters in Moby Dick. It’s like, what comes first? The chicken or the egg? Ultimately, you could say that was the job we wanted.

“The analogy would be Moby Dick when they couldn’t get off the boat. So, you’re stuck together. I was Ishmael, looking for an excellent adventure. Then I met Bob who was Queequeg, who showed me how to hit the whale in the eye from 100 yards. And so, we had this relationship, even to today, where we are stuck together spiritually, and I met these crazy harpooners.

“You could complain whether we got to be the American Beatles or not, but all that. Especially when you think of Skip there are these tragic things. Not just Skip, everybody, really. At some point we all could understand together. When you get in a band with guys, and people out you together, we were all trying to get away from each other.

“Ishmael only survives to tell the story, according to Herman Melville. We didn’t know each other well, that was another problem. And our (former) manager was Ahab. Skippy could see the end but could not stop it. What we were supposed to do was show people how to change the script to Moby Dick so we were all gonna be like the evil captain in the end finally seeking revenge. What we wanted to do was change the script, if we could do that it would be a great example to people. That’s what people in show business are supposed to do. That’s what they are getting paid for. To not get overwhelmed by peoples’ pre-conception of them. The music comes as a result of that.

“Why does the music from the sixties and very early seventies still resonates? Why am I asked about Moby Grape,” pondered Lewis.

“There are reissues and a guy is doing a documentary. There is some part where people think you’re at and they have a nostalgia for the sixties. It’s like the last gasp of humanity. A lot of the sixties was not serious. It was like ‘you’re already dead so why worry about it?’

“Like now we’re in the age of modern slavery. They all want to figure out a way of avoiding that. That’s what those times were all about. Everybody is dropping like flies. So, there’s this thing about the world that is going really fast right now. I’m from a show business family. The people who would come by the house weren’t stupid. Tennessee Williams came to my mom’s house for dinner. I met Gore Vidal. James Baldwin. I knew who they were from being a little tiny kid. I would be listening to them talk about stuff and they were fixated about taking something from the printed page and making it into a movie,” Peter summarized.

(Harvey Kubernik is the author of 20 books, including 2009’s Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon, 2014’s Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972, 2015’s Every Body Knows: Leonard Cohen, 2016’s Heart of Gold Neil Young and 2017’s 1967: A Complete Rock Music History of the Summer of Love.

Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. In 2021 the duo wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s Docs That Rock, Music That Matters. His book Screen Gems: (Pop Music Documentaries and Rock ‘n’ Roll Television Moments) is scheduled for 2025 publication.

Harvey wrote the liner notes to CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, The Essential Carole King, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special, The Ramones’ End of the Century and Big Brother & the Holding Company Captured Live at The Monterey International Pop Festival.

During 2006 Harvey spoke at the special hearings by The Library of Congress held in Hollywood, California, discussing archiving practices and audiotape preservation. In 2017 Kubernik appeared at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio, in their heralded Distinguished Speakers Series).