New Biography and Bowie Celebration Tour in 2018 and 2019

By Harvey Kubernik c 2018

“It is pointless to talk about his ability as a pianist. He is exceptional. However, there are very, very few musicians, let alone pianists, who naturally  understand the movement and free thinking necessary to hurl themselves into experimental or traditional areas of music, sometimes, ironically, at the same time. Mike does this with such enthusiasm that it makes my heart glad just to be in the same room with him.” — David Bowie on Mike Garson

understand the movement and free thinking necessary to hurl themselves into experimental or traditional areas of music, sometimes, ironically, at the same time. Mike does this with such enthusiasm that it makes my heart glad just to be in the same room with him.” — David Bowie on Mike Garson

Pianist Mike Garson was David Bowie’s most frequent musician, on record and onstage, throughout Bowie’s life. They played over a thousand shows together between 1972 and 2004, and Garson is featured on over 20 of Bowie’s albums. In November 2006, Garson accompanied Bowie and Alicia keys for a rendition of “Changes” in New York City at an AIDS benefit which was Bowie’s final public performance in the U.S.

Around his teaching, performance and recording work, Garson is serving as the pianist, bandleader and stage emcee who anchors the well-received A Bowie Celebration spotlighting a flexible touring lineup.

The current touring ensemble is Garson, who was Bowie’s musical director with Luther Vandross and David Sanborn on the Young Americans 1974 tour, longtime Bowie veteran Earl Slick guitar, Gerry Leonard guitar, Mark Plati guitar, Carmine Rojas bass, drummer Lee John Madeloni, who is Slick’s son, and vocalists Bernard Fowler, Cory Glover, Joe Sumner and Gaby Moreno.

Rojas was the bassist on Let’s Dance; Mark Plati was the producer of the Earthling album, Gerry Leonard was Bowie’s musical director in the ‘90s on Heathen and Reality tours.

This past February I saw the Bowie Celebration in Los Angeles at the Wiltern Theater. It was a marvelous tribute. An invited guest, actress and singer Evan Rachel Wood was really impressive with her rendition of “Moonage Daydream.”

On September 28, 2018, the Bowie Celebration comes to San Diego area for a date at Humphreys Concerts by the Bay and a projected return for another Los Angeles appearance during September.

Scheduled for January 2019 are a slew of dates in Europe, England, and North America, beginning January 9th in Dublin, Ireland, with stops in Glasgow, Scotland and Manchester England. The Bowie Celebration band for the 2019 bookings will be a bit different.

“Our show will continue to be an unforgettable and critically acclaimed evening of Bowie songs featuring world class vocalists and an ever rotating mix of hits and deep cuts,” Garson offered. “In April when we played in New York, I brought [saxophonist] Dave Leibman, [Garson’s lifelong musical friend] on stage after 50 years. And he jammed on ‘Aladdin Sane’ and it brought the house down. The band was absolutely in shock it was so good.”

“David had an infinite source of music flowing through him, and his creativity was boundless. His sharing of the stage with his musicians was extraordinary, and he was a team player. That is why we need many singers to encompass his work,” added Mike, who in 2011 composed “A Tribute to David,” which appeared on his Bowie Variations album.

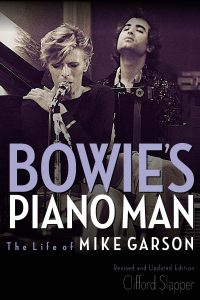

In May 2018, Backbeat Books just published a revised and updated edition – the first in paperback – of the only biography of Garson, Bowie’s Piano Man: The Life of Mike Garson. Written by Clifford Slapper, a fellow pianist who also played for Bowie, working closely with him on his last-ever television appearance.

Bowie’s Piano Man explores the special relationship between Garson and Bowie, beginning with the extraordinary story of how a young New York jazz pianist had his life transformed overnight after one short phone call in 1972 from Bowie’s manager. Special to this new edition is a foreword written by Garson himself and in-depth conversations with Garson, focusing on the effect Bowie’s death has had on his friend and colleague of 45 years.

A noted master of jazz, classical, fusion, and experimental genres, the book explores Garson’s commitment to improvisation as a form of composition, a manifestation of his more general dedication to living in the moment and always moving forward–a trait he shared with Bowie.

Bowie’s Piano Man shares the story of his childhood in Brooklyn, his ongoing strong presence in the jazz world; his collaborations with a huge range of other artists in addition to Bowie, including the Smashing Pumpkins and Nine Inch Nails; and his unique ability to live the life of a rock and roll star while abstaining from drugs and alcohol and keeping his family life intact. This searching biography is also a chronicle of how musical boundaries are broken down and how new genres are created.

In this revised and updated edition, there are new photographs as well as six new chapters, including Garson’s personal recollections of “life on the road with David Bowie” over the course of the nine world tours in which they played together. These new chapters also contain several more interviews with friends and collaborators such as Billy Corgan of the Smashing Pumpkins, producer Ken Scott, who worked on six Bowie albums, and saxophonist Donny McCaslin, who led the Blackstar band.

Clifford Slapper, from London, England, grew up against the background of the glam-rock scene. He became a pianist, having been inspired, at age 11, by Mike Garson’s piano on Bowie’s 1973 album Aladdin Sane. Going on to be one of the UK’s top pianists, playing with many great artists such as Boy George, Marc Almond, and Lisa Stansfield, he finally worked closely with David Bowie himself, playing for him on his last-ever television appearance. He also works as a producer, arranger, and composer and has recently produced the album Bowie Songs One, which reinterprets Bowie’s songs acoustically for piano and voice.

In the press release for Bowie’s Piano Man, Slapper states, “At the age of 11, I ran home through the streets of Wembley to my parents’ ‘Dansette’ record player with its legs off, clutching the first record I had ever bought: an album of 12-inch vinyl in a gatefold sleeve. It was David Bowie’s Aladdin Sane, in the spring of 1973, and as the bright orange RCA label started spinning at 33 and a third revolutions per minute, I was transfixed. The opening two chords of ‘Watch That Man,’ a G and a C, were an apt fanfare for the start of my adolescence.

“In particular, it was the piano playing by Mike Garson on that album which was a revelation. I had been playing the piano since I was seven, but this gave a whole new purpose to my studies. It sounded bright, at turns both melodious and unnervingly discordant. Like shards of broken glass, his rapid, cascading high notes danced over his rumbling, thunderous bass runs. I knew then, this was what I wanted to do.

“I went on to become a pianist myself, always inspired by Garson as well as Bowie, and I have played with many artists (Boy George, Jarvis Cocker, Gary Kemp, Marc Almond, Holly Johnson) who have declared themselves hugely influenced by Bowie and albums such as Aladdin Sane, Pin Ups, Diamond Dogs, Young Americans and David Live – all of which Garson played on.”

Michael David Garson was born in New York City on July 29, 1945. He studied classical composition with Leonard Eisner of Juilliard. He earned degrees in Music and Education from Brooklyn College. He also studied with Lennie Tristano, Bill Evans, Herbie Hancock, and Hal Overton. He has played with hundreds of musicians and singers. Mel Torme, Jackie Mason, Martha and the Vandellas, Stanley Clarke, Elvin Jones, Lee Konitz, Freddie Hubbard, Stan Getz and Lulu.

Since 1982, Mike has been a member of Free Flight, a jazz and classical ensemble featuring flutist Jim Walker. He’s also recorded with Billy Corgan and Smashing Pumpkins, No Doubt, and Trent Resnor and Nine Inch Nails. With Corgan he co-composed the score for the film Stigmata. Their collaboration “Identity” was performed by Natalie Imbruglia. In 2014, Garson and Trent Reznor did “Just Like You” for the movie Gone Girl.

Garson has taught students at master classes and through private instruction and has appeared at universities around the world as both guest lecturer and performer. This decade Garson, who grew up wanting to be a doctor, he was pre-med at Brooklyn College in 1963 before the piano playing portion of his brain took over, began to discover the effect and the power that music can play in the healing process and teamed with Dr. Chris Duma, a Newport Beach-based brain surgeon specialist, to further explore the possibilities.

On March 1, 2014 at the Segerstrom Hall in Costa Mesa, California, Garson premiered his commissioned work, “Symphonic Healing Suite,” a set of original music compositions, written in collaboration with patients dealing with various disorders and ailments. A follow-up concert, Music Heals II, in conjunction with the Foundation for Neuroscience, Stroke and Recovery, took place on November 2, 2014.

Before fall 2018 A Bowie Celebration dates in California, including one in San Diego at the Humphrey’s venue, and the January 2019 tour of Europe,

Garson is doing some solo shows in England during August booked as An Evening with Mike Garson and Friends.

I devoured the delightful Bowie’s Piano Man and conducted a 90 minute phone interview with Mike from his home in Bell Canyon, California.

Q: I saw the David Bowie 1972 Ziggy Stardust Bowie show in Santa Monica, California. Until the official live recording came out from the original KMET-FM radio broadcast, it had been widely bootlegged. I never knew you were on stage. I don’t recall your piano anywhere in the sight line.

A: I was there. It wasn’t my choice. I was just placed there. And I assumed because I was an ‘add on’ member I wasn’t part of the Spiders From Mars. And I was just the piano player off on the side just playing.

Q: I met Bowie a few times and interviewed him in 1976 for Melody Maker at Television City in Hollywood. David commented about this memorable event.

“I can tell that I’m totally into being Ziggy by this stage of our touring. It’s no longer an act; I am him. This would be around the tenth American show for us and you can hear that we are all pretty high on ourselves. We train wreck a couple of things, I miss some words and sometimes you wouldn’t know that pianist Mike Garson was onstage with us, but overall I really treasure this bootleg. Mick Ronson is at his blistering best.”

Some of the time on your 1972 eight-week Bowie tour, when a piano wasn’t needed half the time on the stage repertoire, you’d be in the front row and watch the action, like when Bowie would do his acoustic “My Death.”

A: David and I played the song at a fundraising event at the Manhattan Center in 1995. There were so many great performances throughout the evening but David just tore the house down with this most riveting performance of “My Death.” No one ever performed this Jacque Brel song better than David.

Q: And we really know later in the decade you were present on stage and really heard like on the album David Live.

A: I love that album. And Tony Visconti re-mixed it and really pumped up the piano. [laughs].

Q: One of the strengths of your book is that the writer Clifford Slapper is a keyboardist and the text weaves biography, technical and musical instruction and plenty of reflections on Bowie.

A: You’re absolutely right. He called me. He lives in England, told me he was a piano player and worked with singers. And he loved Bowie and when he was age 12 he had a lovely classical music teacher and that he heard Aladdin Sane and it changed his life.

Q: How did the concept for the actual book begin?

A: So 40 years later he was taking a piano lesson from me and we were chatting and he told me he studied history in school. I suggested he write a book on my life. ‘I’ll answer as many questions as I can and I’ll turn you on to the various artists that you could interview.’ He then came out for a few days and we did a lot of taping over 24 hours. I then sent emails to people like Billy Corgan who happily spoke to him.

Q: In the book you admitted you never drank, touched a drug and have been married to the same woman since 1968. Nice to read an biography on a musician with a 50 year career who never got high. Particularly a person who could be referred to as a jazz musician.

A: Well, I’m 72 now. So I’ve been telling everybody I won’t start drugs until 75. [laughs]. I had to be mature enough.

Q: Maybe it helped or aided aspects of your memory or recall abilities. You never kept a diary.

A: No I didn’t. I’ve always been all about the music whether I was playing, classical, jazz or rock or writing my own stuff. In some ways I feel like the last man standing as I have experienced the loss of many people and musical giants. And, as you get a little older I think it’s sort of your job to play it forward, not in a heavy way or to prostalyze. Tell it like it is and giving some people hope that there doesn’t have to be the dark side.

Q: I know that when you got the Bowie job in 1972, you had some jazz friends, or jazz snobs who looked down at pop and rock music, and weren’t all that supportive or enthusiastic about you “leaving jazz.”

A: Some thought it was way beneath me. I loved piano, improv, jazz, classical and I didn’t care if it was pop, jazz, new age, fusion, gospel, a mixture. None of it mattered to me. I just loved the piano and they were stuck in only Be Bop which already we had moved out of that. So they weren’t even being fresh jazz players.

I would rather play with Bowie who is doing cutting edge music than some guys playing Charlie Parker and Bud Powell licks from 1949 in the seventies. I could do that, and I can still do it as well as any of those guys, but it’s more historical. Like I do Chopin, Bach or play Beethoven. It’s not the Miles Davis attitude or the Bowie attitude or the Lennie Tristano attitude where the music exists around you and you connect it to life. And yes, that music is great. And I can’t tell you how many $5.00 jazz gigs or $50.00 jazz gigs I’ve done in my life.

I was so submerged in jazz I was a little like some of those jazz pricks. My life was jazz. But when I started to grow up and realize music and life is bigger and there were the David Bowies of the world for my understanding and openness.

There must have been 100 concerts with Bowie where I played to 10-30,000 people, and I was thinking when I was playing, “I wish I was in a jazz club.” [Laughs].

Q: What I found interesting about your pre-Bowie life, you seemed to have no connection whatsoever to rock and roll of New York and Brooklyn of the late fifties and sixties. You were always in the jazz world even as a kid and student.

A: I had no involvement. Cousin Brucie a deejay on New York radio lived in our building.

Q: You saw John Coltrane around 1960 in New York.

A: As a teenager with Dave Leibman. John Coltrane, Eric Dolphy and Elvin Jones at the Half Note club. Here’s my Coltrane experience: LIFE CHANGING. INSPIRING. DEEP INTEGRITY. CREATIVITY BEYOND. Other than that nothing!!

Q: You later work with Elvin Jones.

A: One of the greatest moments in my life. I learned a lot. Supporting the leader but playing as one. I’ve called it playing within the window.

Q: You went to see the pianist Thelonious Monk one evening and Monk, during his stage dance, maybe he was drunk, fell off the podium and you caught him.

A: At the Village Vanguard in 1963! After Monk played piano, sax player Charlie Rouse would solo and Monk would be moving around the stage going in a circle. At the Village Vanguard you could sit right near the piano and I saw him going down and so I caught him. He must have weighed 300 pounds.

Q: As a teenager you studied with pianist Lennie Tristano.

A: I took lessons from him for three years. He taught me left hand voicings over a two year period. When I was studying jazz in new York, and heard Art Tatum, McCoy Tyner and Cecil Taylor and it was the best place for an education. I saw Bill Evans and he gave me a free six-hour piano lesson. I remember looking up to him on the stage. Same thing happened when I saw Arthur Rubenstein.

Q: Artist, singer and performer Annette Peacock was the one who recommended you to Bowie for your audition.

A: She is another unsung hero. There is a song David wrote called “Something in the Air.” There are some live tracks of it from Paris in the nineties. It’s one of David’s greatest songs. He sounds like Annette Peacock on it. For those who know her, you can hear the great Annette Peacock’s influence on David. She’s an avant garde singer and she recommended me to David for the first Spiders From Mars tour in America. I played on her album, I’m The One. David and Mick Ronson loved her artistry. She’s an unsung hero.

Q: You did a bit of “Changes” at the audition for the Bowie job inside a Manhattan studio after driving from your house in Brooklyn. You’re in jeans and there’s Bowie with red hair and Mick Ronson with silver hair with knee-high boots.

A: Mick gave me the music for “Changes” and said, “Play this!” I play a few seconds and he says, “Ya got the gig!”

The thing with David was all so surreal. I didn’t know who David was. I was a jazz guy. I didn’t take it too serious although I recognized he was quite a talent. It was one of those things that all my best gigs that I’ve ever gotten was when I was out of my own way and they just sort of happened out of nowhere. He gave me more freedom than other singer I ever worked with. And I’ve worked with a 1,000 singers. He just had that jazz sensibility and trusted me. It raised my level of playing each night. And my playing doubled over the next year or two.

Q: In reading your book I was reminded again how important guitarist/arranger Mick Ronson was in the world of David Bowie.

A: Well, he’s the unsung hero. When I joined in 1972 on stage it gave him more room. Mick was a wonderful guy and very humble. And he knew how to solo great. He was very inspirational. When you recorded with all these great musicians and this pertains to Mick, who was there and inspiring me. It’s like the notes found me more than I found them.

Q: When you were recording with Bowie, were you even aware of the words and lyrics of his tunes? In your book you focus on the music, melody and sound but never quote a lyric or reference them.

A: I never thought about the words consciously. He could have been humming.

Now that he’s gone I’m really hearing the lyrics, and the music and songs are so strong. I really believe his work on stage would have worked without the clothes and make up. I got an energy from him. I always loved performing so now every night I play every piece as something different. When I play now, and this was evident with David, it’s a community activity. Like when I do my healing music. I learned from watching. I’m not an entertainer. I don’t sing and dance. But I tell some nice stories and play the piano. If you follow your heart and are honest things work out.

Q: I hear the Latin jazz influence on the original 1973 “Aladdin Sane” track. Your piano playing brings in Latin elements. Very percussive touch on the keys. Where did this influence come from?

A: I had worked with Eddie Palmieri, plus I worked opposite Larry Harlow, [American salsa musician] earlier in the Catskills with Dave Leibman. I showed Bowie some stuff.

Q: I love one live version you did on David Live with percussionist Pablo Rosario.

A: Anything that I had done prior to working with David I could do on his sessions or in concerts. On that Aladdin Sane album and songs like “Aladdin Sane” and “Time,” Ken Scott was very involved in the high frequencies and EQ. An extraordinary producer, engineer and mixer. I worked with him and David at Trident, where the Beatles did some [1968] recording. It was two chords, an A and G chord, and done in one take. David’s son, Duncan once admitted to me that he was petrified of my “Aladdin Sane” piano solo and that they gave him nightmares.

Q: In 2012 I interviewed Ken Scott, specifically about Bowie’s use of piano on his 1971-1973 albums.

“One of the things in looking back on the Aladdin Sane period that has fascinated me was that I didn’t realize it until recently, was the way piano changed David’s music. It occurred to me how a certain amount of David’s transformation, you take Hunky Dory which had Rick Wakeman on it, who is a fantastic, a bit more classically-oriented pianist, ‘Life On Mars,’ very good at rock ‘n’ roll but his training was more classical. His piano on ‘Life On Mars’ is unbelievable.

“Then you go into Ziggy Stardust, with Bowie and Ronno playing. On Ziggy, it’s really simplistic because they weren’t pianists. Neither of them particularly awe-inspiring. So the piano is very simple on Ziggy.

“But then you to Aladdin Sane, Mike Garson is on board, and it completely changes the whole feel of it. Now how much of that is pre-planned by David to move it into a different direction and how much is their effect on the way that we recorded I don’t know. The Beatles kind of grew by using different instruments. Bowie changed and grew by using different people playing. It’s bizarre. His use of keyboards really does sort of cover his growth and how he changed.”

Q: You might be the only New Yorker I’ve ever encountered that doesn’t waste any negative energy bad-mouthing Los Angeles and Hollywood constantly. Your life in Southern California has been the antithesis from David’s short narcotic haze mid-seventies Beverly Hills and Hollywood visit.

In 1973 you’re on Aladdin Sane, heard on the selection “Cracked Actor,” which has a regional lyric reference to “Sunset and Vine,” and years later you are playing up the street in Hollywood at a club Two Dollar Bill’s on Franklin Ave.

A: Before we moved to Bell Canyon, we did 20 years in Southern California in Woodland Hills. I love it here but I still go back to New York.

Q: I really dig the Young Americans album. Tired of “Fame” but play “Fascination” at least once a month.

A: Great song. David Sanborn.

Q: The recording “Somebody Up There Likes Me” is fantastic.

A: I agree. David Sanborn…I need to do that song on the tour next year. I love that song. The prodding slow beat on the studio recording.

Q: Somebody Up There Likes Me was a movie that actor Paul Newman had starred in. In my 1976 interview with Bowie, I asked him about his relationship to film, recording and performing.

“The difference between film acting and stage acting is enormous,” he stressed. “On stage you are in total control, whereas in a film the actors are instruments of the director. I think a stage performance is more of a ceremony and one plays the high priest. But in a film you are evoking a spirit within yourself. You feel a tremendous responsibility of having the power to bring something to life, for example Major Tom in ‘Space Oddity.’”

A: “Space Oddity” has always been close to my heart. I did this arrangement for a children’s choir and small orchestra a few years ago and it has so much depth and feeling that it feels like I did it just this morning.

We just did ‘Can You Hear Me” at a show last year and it was fantastic. Luther Vandross was a background vocal genius. He would bang out every note to make those background vocals sound amazing. David was the best at finding the right people. Mick Ronson, Luther Vandross, Carlos Alomar, Stevie Ray Vaughn and let them do their thing. Whatever I had practiced I could do. “It’s Gonna Be Me” was a bonus track from the [1991 reissue] Young Americans album. It’s very deep and Very naked. This mix was really just piano, bass and drums. Then the strings and background vocals. Luther is leading the wonderful background vocals.

Q: “Wild Is The Wind” is from Station to Station. I was at a couple of the LP’s recording sessions at Cherokee studios. It’s a Dimitri Tiomkin and Ned Washington tune. Nina Simone sang it for a movie.

A: David used to like covering that song because he liked Nina Simone.

Q: At the Bowie 2004 show at the Wiltern Theater in Los Angeles, the band covered Neil Young’s “I’ve Been Waiting For You.” And David asked a local deejay, Rodney Bingenheimer to introduce him to the audience at his concert.

A: I remember that.

Q: In 1970 Rodney was David’s record promotion man at Mercury Records on Hollywood Blvd. who took David to FM radio stations for his first airplay in the Southern California area and put together the press party where David performed acoustically to promote The Man Who Sold The World. And a third of a century later Bowie acknowledged Rodney’s initial efforts on his behalf. That sort of loyalty doesn’t happen in Hollywood these days.

A: David was an explorer and was locked into his music. In the 1972-1974, I was with David he fired five different bands and I was the only one he kept. Because I was able to change styles and go from the English rock to the avant garde to the soul and gospel stuff. And that was the only reason he kept me and that we were friends. But he saw that I could go with him as he was ever-changing. And he knew as a jazz musician I was always looking and searching. Because I carried the spirit of what an improviser was. Lennie Tristano really didn’t allow me to play licks. I always had to play something fresh.

Q: I know on tour you David and band members usually ate dinner before the gig at the venue, and sometimes after a show the promoter would take you guys out for a big nosh. But you and David hung out.

A: Yes. On tour we would talk about a lot of things. Charles Mingus. Stravinsky. Alan Watts. Classical music.

Q: In your book you detail one evening where David invited you over to his hotel suite to watch Frank Sinatra and Elvis Presley movies.

A: Yes. I had only known David two weeks at the time. He would do imitations of them and ask me how he was doing. He had that much respect for me which was shocking.

Q: David and Elvis share the same Birthday in January.

A: That doesn’t surprise me.

Q: You had your own encounter with Sinatra.

A: It was unbelievable. Frank Sinatra used to like this standard, “When Joanna Loved Me.”

Q: He recorded it. Scott Walker also cut it.

A: In 1980 I think, I was in his jazz trio in Lake Tahoe with Kenny Colman singing. Sinatra came to see us and watched our set and came up to me and thanked and acknowledged me for my piano playing. A few years later I had a chance to go out with him but I decided to go out with Stanley Clarke and play fusion instead. [Laughs].

I was with Stanley Clarke in 1979 at Carnegie Hall and our opening act was Eubie Blake. He was celebrating his 100th birthday. He had the longest fingers. They were frightening. I stood right by him on stage and said hello. The guy was 100 and I said, “I want to do that.”

Q: You cite a discussion you had with Bowie in the book where David one time predicted his death in the age 69-70 period. He died on January 10, 2016, two days after his 69th birthday, which is what exactly happened.

A: In the late seventies or early eighties David said “I’m going to die, you know, around 70,” of that nature. He said it to me like we’re talking. He didn’t question it. He didn’t have fear about it. It was matter of fact. And virtually he planned his life that way.

Q: In reading your book and journey through music, you inevitably become a messenger for some now silenced voices, especially David Bowie. After his death you really embraced your musical partnership with David, and not lamenting or distancing yourself from him posthumously. .

A: Yes. I felt him. I did. I think, without getting “too out there,” I felt he was communicating to me from the other side to “do it” and “take over” and see what happens. I really enjoyed playing “Word on a Wing” with David as I felt it to be a very deep song and maybe a cry for help. I hope he gets many of his questions answered now.

Q: In your biography you indicate you sort of took your David Bowie experience of the seventies for granted. You were thankful and very happy, but it wasn’t some super life-altering event for you. But now it appears you feel another way about that expedition.

A: Now that I looked back and have spent time on it I’m remembering and looking at my life with David 1,000 times bigger. I’ve been asked and when he was alive to do 30 tribute bands. I passed. Why would I want to do that when I had the real guy? I’ve always been playing jazz and classical gigs. But once the real guy wasn’t there I could get the music and his compositions out there. I grew up on Cole Porter, Rodgers and Hart, and realized David was a great songwriter.

(Harvey Kubernik is the author of 14 books. His debut literary music anthology Inside Cave Hollywood: The Harvey Kubernik Music InnerViews and InterViews Collection, Vol. 1 was published in December 2017, by Cave Hollywood. Kubernik’s The Doors Summer’s Gone was published by Other World Cottage Industries in February 2018. In November 2018, Sterling/Barnes and Noble will publish Kubernik’s The Band From Big Pink to the Last Waltz.).