By Harvey Kubernik © 2019

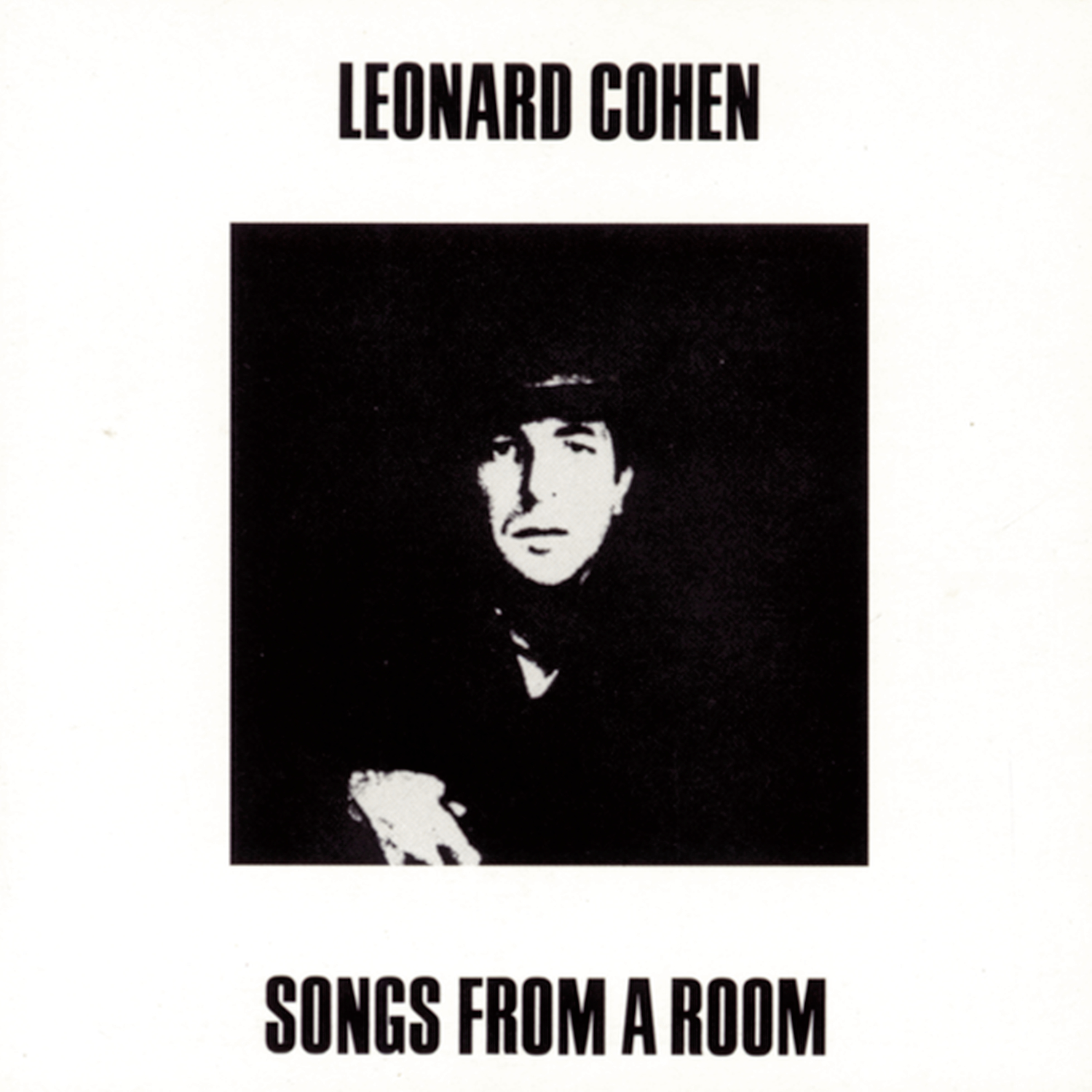

April 7, 2019 marks the 50th anniversary of Leonard Cohen’s second Columbia Records album, Songs From A Room in 1969. It reached No.

63 on the US Billboard Top LPs and No. 2 on the UK charts.

“Initially, Songs From A Room felt like a trespass,” suggested writer Marina Muhlfriedel. “How dare Leonard Cohen dilute the sacred incursion his first album, forged into my being? For some reason, I never considered the possibility of a follow-up. Songs of Leonard Cohen was so personal, so monolithic, I assumed it to be a singular event.

“It took a friend planting me on a couch, cranking up the speakers and demanding I listen. Before ‘Bird On the Wire’ was over, tears flowed. It was so damn beautiful — a hymn, a confession, a deep bow of humility striking a nearly unbearable nerve. Leonard seemed a bit older, wearier, less embellished, but once again that trickster sunk right into my soul.”

“Leonard wrote songs because he had to, and because he wanted to get laid,” observed author, record producer and deejay Andrew Loog Oldham in a 2014 interview we conducted. “Later he wrote songs because he wanted to get paid. That’s when I decided he had something to say.”

I was on the UCLA campus in Westwood, California when Cohen debuted in 1970 at Royce Hall. Michelle Phillips of the Mamas & the Papas was one of Leonard’s singers that evening. Mama Cass Elliot had already covered “You Know Who I Am” from Cohen’s Songs From A Room on her 1968 album Dream a Little Dream.

I later attended his 1974 Troubadour club shows in West Hollywood. Around the same time, a Columbia Records label publicist or Leonard’s booking agent Stan Goldstein at Magna Artists invited me in 1974 to a spell-binding Cohen recital in downtown Los Angeles at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion.

Cohen must have done four encores. Leonard turned to the musicians, grabbed a book from his pocket and started to read poetry while the band vamped behind him.

I hadn’t witnessed anything like that since a Doors’ concert in November of 1968 at the Inglewood Forum when Jim Morrison stopped the action, in front of 17, 505 fans, asking an audience member for a cigarette and proceeded to preview passages from his upcoming The Lords and New Creatures poetry book.

I was really surprised when Leonard invited everyone in the audience backstage to say hello.

There was no guest list or pest list.

I introduced myself to Leonard in a hall way, ‘can we do an interview the next time you play L.A? I’m trying to be a music journalist and I have to pay the rent.” He replied, “That would be fine my friend.”

On his next visit, a Columbia Records publicist telephoned, arranging an interview at The Continental Hyatt House on Sunset Blvd.

“I used to be petrified with the idea of going on the road and presenting my work. I often felt that the risks of humiliation were too wide,” Leonard explained in our first Melody Maker interview. “But with the help of my last producer, Bob Johnston, I gained the self-confidence I felt was necessary. My music now is much more highly refined.

“When you are again in touch with yourself and you feel a certain sense of health, you feel somehow that the prison bars are lifted, and you start hearing new possibilities in your work.

“I don’t have any reservations about anything I do. I always played music. When I was 17, I was in a country music group called the Buckskin Boys. Writing came later, after music. I put my guitar away for a few years, but I always made up songs. I never wanted my work to get too far away from music.

“Ezra Pound said something very interesting in ABC of Reading. ‘When poetry strays too far from music, it atrophies. When music strays too far from the dance it atrophies.’”

It was in May 1968, when Joni Mitchell, having just recorded her first album, Song to a Seagull, produced by David Crosby, implored Crosby to do some tracks in Los Angeles with Cohen. It was not a constructive pairing. Three songs were cut and two were eventually issued on a 2007 CD as bonus material.

Crosby, by his own admission, had no real production skills and was ill-prepared to grapple with Cohen’s sui generis material. But this time in Los Angeles wasn’t completely without value. At the airport Cohen crossed paths with Bob Johnston, a man with stellar producer’s credentials, who had been in the studio along with John Hammond and John Simon jointly producing Cohen’s first LP. This chance encounter planted the seed for what would become the follow-up.

Toward the end of the promotional cycle for his debut album, however, Cohen fell into a funk, experiencing a creative and emotional exhaustion which may have reflected his deep-seated ambivalence to success. Viking, his American publisher, had no qualms about promoting his new-found “pop star” status, bringing out a new edition of his 1966 novel Beautiful Losers as well as an anthology, Selected Poems 1956–1968, shortly after.

As fall approached, Cohen was finally ready to commit to a new album. It was his long-cherished dream to record in Nashville and sidle down to “Music City.”

Bob Johnston was now running Columbia’s Nashville operation. Johnston was born in 1932 in Hillsboro, Texas. Johnston held a staff song writing position at Elvis Presley’s Hill & Range Music, and then had peripatetic stints talent scouting for Kapp and arranging for Dot Record labels, before joining Columbia Records in 1965 and helming studio productions with Johnny Cash, Bob Dylan, including Blonde On Blonde, and sessions with Simon & Garfunkel on Sounds of Silence, Parsley Sage Rosemary & Thyme and Bookends.

“I caught him at an airport in Los Angeles in spring of ’68 for the second one,” Johnston remembered in a 2014 interview we did. “And he asked me to produce him and I said ‘I’m in Tennessee now.’ He always wanted to go to Nashville. The Buckskin Boys were his first little band.”

Fresh off the heels of producing Bob Dylan’s John Wesley Harding LP in late 1967, and then recording the Johnny Cash At Folsom Prison album, Johnston and Cohen talked about Leonard’s second disc for Columbia.

Never one for formality, Johnston treated his artists with the wariness of a rattlesnake wrangler, giving them all the space they needed to find their creative core.

“When Leonard first came to town he was in an old person’s hotel and stayed about the first week,” howled Johnston. “And then me and [songwriter] Joy [Byers], my wife, leased acres from Boudleaux Bryant and his people and it was a little house by a creek. And then Leonard looked at this house and went all through it, and saw the 1,500 acres, and he said, ‘One day I’ll have a house like that and I’ll be able to stay and write when I want to write.’ And I replied, ‘Why don’t you just begin now?’ And I gave him the key and he moved in.

“Leonard and I walked into Columbia Studio A. It had a bench there. A little stool. He said, ‘I want to play my song.’ And I said, ‘We’re going to get some hamburgers and beer.’ And he said, ‘I want to play my song.’ I said, ‘Go ahead and play it and turn the button on there.’ ‘No. I want you around.’ And I said, ‘I want to get some beer.’

“So we walked over across the street to Crystal Burgers, he came, had a couple of hamburgers and beer and came back. ‘What do you want me to do now?’ he asked. I said, ‘Why don’t you get your guitar and tune it?’ And he looked at me, so I had his guitar tuned, and he got on the stool. And I said, ‘Play anything you want too.’ OK. Roll tape. And Leonard played the song ‘The Partisan.’ And he got through it and asked to hear it. ‘Yeah.’ Played it back to him. He looked at me and said, ‘God damn. Is that what I’m supposed to sound like?’ And I said, ‘Forever.’ And there it was.”

Johnston, as he did previously in the Nashville sessions for Blonde On Blonde, took steps to remove the studio bafflers, a floor space dividing device used to prohibit microphone leakage and the instruments of the musicians from bleeding into each other’s separate sound booths during the sessions. The technique aided the stark sonic results.

“I’ll tell you something else I did recording Dylan, and Cohen,” he added. “I put them in the studio booth surrounded by glass and air where it used to be wood. Now everybody else could walk around and see them and talk to them. And that’s the way that it was.

“Everybody else was using one microphone. What I did was put a bunch of microphones all over the room and up on the ceiling. I wanted it to be where everybody could hear it. I always had four or eight speakers all over the room,” exclaimed Johnston.

“I had the engineer Neil Wilburn—did the Cash Folsom Prison live album with him. And he was a genius behind all that shit. I had a great thing with anybody who was a genius.

“I put together the studio band for Leonard. I hired all those guys who were doing the demos from the South. Charlie McCoy [harmonica and guitar], Charlie Daniels [bass, fiddle, acoustic guitar] who I knew from 1959, Ron Cornelius [acoustic and electric guitar], Elkin “Bubba” Fowler [bass, banjo, acoustic guitar]—and I played keyboards. I did a record with Ron Cornelius’s group [West] in 1967.

“We did about ten studio sessions,” reiterated Johnston. “I always ask the artist ‘What do you want to do?’ You get better performances when you make the artist comfortable. Dylan, Cash, Cohen were just wonderful people and they should be treated as such.

“What attracted me to Cohen and songs like ‘Bird On the Wire?’ What attracts you to Leonardo da Vinci? Leonard was the best I’d ever heard. And Dylan was the best I’d ever heard. And [Paul] Simon was the best I’d ever heard. And Cash was the best I’d ever heard. And all those fuckin’ people were the best I’d ever heard.”

Multi-instrumentalist Charlie Daniels hailed from Wilmington, North Carolina and first came to Nashville courtesy of Johnston, his longtime friend.

“I went back to 1959 with Bob Johnston,” remembered Daniels during a 2014 interview with me. “I met him when I went through Ft. Worth Texas on my way to California for the first time with a band. Bob was working at Bell Helicopter in the day time and at night trying to get something going record wise or songwriting at night time.

“So we wrote something together at his mother’s house, an instrumental called ‘Jaguar.’ We struck up a friendship there. In 1962 and Bob said ‘let’s write.’ So I had this idea for a song, the basic, ‘it hurts me.’ ’OK. Let’s write that one.’ At the time, Bob was staff writer for Hill and Range which handled Elvis Presley’s music publishing. And they held it for a year and finally decided to record it. ‘It Hurts Me’ that Elvis Presley recorded and put on the flip side of ‘Kissin’ Cousins.’

“And when Bob moved to Nashville in 1966, he called me and said, ‘Why don‘t you come to Nashville?’ And I always wanted to live there and packed up in 1967. He had just done Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde. All the good things that happened to me in the early days were because he was a cog in the wheel.

“One thing that needs to be said about Bob Johnston and bringing people to town like Dylan and Leonard Cohen. There was skepticism about Bob coming to Nashville because he was taking the place of a legendary producer, Don Law, who was an institution in town.

“Here’s this guy Johnston from New York, who had been doing Simon & Garfunkel, Dylan, and now Leonard Cohen, who were not really thought of as being country. But the first thing Bob did when he came to town was to do a number one song with Marty Robbins. And in ‘68 produced the albums John Wesley Harding, The Story of Bonnie and Clyde, and of course, Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison. He had gained credibility.

“He was also at the same time, bringing Al Kooper, Dylan and Leonard Cohen into town who had never lived here. Dylan recorded in Nashville in 1966 for a while, but it was he’d come to town, do his stuff, and leave. Dylan happened to record in a studio in Nashville and worked in it.

“Leonard came to Nashville in September of 1968, and lived locally in a cabin. I actually picked up Leonard Cohen at the airport when he arrived in Nashville with his friend Henry Zemel from Montreal. Johnston was booked in a studio. I had long hair and a mustache. I didn’t know who Leonard Cohen was. I knew he was a recording artist and comin’ to town and that we were gonna do some sessions with him.

“I didn’t know what he did. I knew he had a song called ‘Suzanne.’ You don’t know what to expect when you go to meet somebody for the first time that is a totally different kind of music than anything you’ve ever been exposed to. You don’t know what kind of personality they have or what they’re gonna be like. But it was a very pleasant surprise that Leonard Cohen was as down to earth and nice as he could be.

“I will never forget that when he came to Nashville he lived out in the country for a while. And there was a guy who lived out there, an old cowboy called Kid Marley, if there ever were opposites, I mean people who came from totally opposite ends of the spectrum it was Leonard Cohen and Kid Marley. But they just hit it off and got to be friends. Leonard was just that kind of guy. He spoke a different way than everybody else around there did. But he had a great sense of communicating with people,” underlined Daniels.

“The Columbia Studio A was on 16th Avenue in Nashville and was union. In Nashville, in the studios, you had to have the machines to be a certain distance away from the boards so the engineer could not work them both. But the thing I remember mostly about Studio A., the big studio, it was the new studio.

“The old studio, the Kwansit Hut, was the legendary studio where the hits had been cut. Everybody wanted to work in that room. Nobody wanted to work in the big studio until Bob Johnston came to town and basically took it over. Nobody else wanted to be there. He worked with it, got engineers he enjoyed working with like Neil Wilburn, and he actually brought an engineer from New York with him when he first came down,” reinforced Daniels.

“I did learn from working with Johnston and Cohen that ‘less is more.’ I came out of the nightclubs, 13 years of beating my brains out playing every kind of music you could think of. You played the hits of Marty Robbins, Stonewall Jackson and Little Richard. So I played a variety of music. Most of it was bang, slap, get it going, turn it up loud and let it rock. And to go play music with a guy like Leonard Cohen, whose music was so fragile, you just stayed out of his way. That was basically what you wanted to do.

“The best way I know to describe it is that you listen to Leonard and his guitar. Wherever he was, wherever there was a part that you’d think you would do or that would interfere with you, just stayed out of it. You didn’t try to embellish what he was doing. You didn’t try to guide what he was doing. You just tried to fit in. And there was whole mind set to that. And after I got used to the mindset it went really well. That was the approach to it. It was relaxed.

“Now Leonard Cohen tuned his guitar down a full step and how he played it I could never figure out,” marveled Daniels. “Because he had his string tuned down a full step and he played a gut string guitar. That’s impossible. I mean, in my world I couldn’t do it. No way. My touch has never been that soft. And to have a touch that soft…That was the thing about his music though. It was so fragile. It was so ‘stay out of the way.’

“Must have done ten songs, including ‘The Partisan,’ Five or six were on Songs From A Room, and another on his next album, Songs of Love and Hate. I’m on ‘Bird On the Wire’ that has been covered by many people.”

Renditions of “Bird On the Wire” have been done by Jennifer Warnes, Joe Cocker, Jackie De Shannon, The Neville Brothers, Tim Hardin, Willie Nelson, Madeleine Peyroux, Pearls Before Swine, Johnny Cash, k.d. lang and Adam Cohen.

“Bird On the Wire is one of my favorite songs,” volunteered multi-instrumentalist Sarah Kramer, who played trumpet on Cohen’s Dear Heather album.

“I love the rawness and simplicity of the recording he did on Songs From A Room. I love that Leonard played Jaw Harp (or Jew’s Harp) on it too.

“Lust, love, passion, desire, temptation, the human condition… yet never stray(ed) from truth, integrity, from God, from what is right, purity. There’s always a return to harmony.

“There is freedom, but discipline. Permission, but not free from consequence. Living in truth… There’s commitment to that, even if nothing else. Acceptance, but still willing to attempt. Acknowledgment of failure(s), of stumbling, while honoring and serving that which transcends. The beauty in the ugly, the cleanliness within filth. The promise to try. The giving beyond any selfishness.

“Empathy. Humanity. Honesty. This song is everything, it’s how Leonard lived. It’s who he was. I miss him. We all do.”

In a 1992 interview with Paul Zollo in SongTalk, Cohen discussed his fabled “Bird On the Wire” copyright.

“It was begun in Greece because there were no wires on the island where I was living to a certain moment. There were no telephone wires. There were no telephones. There was no electricity. So at a certain point they put in these telephone poles, and you wouldn’t notice them now, but when they first went up, about all I did was stare out the window at these telephone wires and think how civilization had caught up with me and I wasn’t going to be able to escape after all. I wasn’t going to be able to live this eleventh-century life that I thought I had found for myself. So that was the beginning.

“Then, of course, I noticed that birds came to the wires and that was how that song began that’s also set on the island where drinkers, me included, would come up the stairs. There was great tolerance among the people for that because it could be in the middle of the night. You’d see three guys around each other, stumbling up the stairs and singing these impeccable thirds. So that image came from the island: Everything was being finished. The sixties were being finished. Maybe that’s what I meant. But I felt the sixties were finished a long time before that.

“I don’t think the sixties ever began. I think the whole sixties lasted maybe fifteen or twenty minutes in somebody’s mind. I saw it move very, very quickly into the marketplace. I don’t think there were any sixties.”

In 1972 Jennifer Warnes went on tour with Cohen as a background singer. She had auditioned at Columbia Records in Nashville for Leonard and Bob Johnston, and subsequently sang “Bird On the Wire” nightly with Leonard.

“I read anything by Leonard Cohen I could get my hands on,” Jennifer recalled to me in a 1977 interview for Melody Maker. “When I heard there was an opening in his band I rushed right over.”

Warnes is heard on Cohen’s Live Songs culled from his 1972 Europe trek. “I remember the last concert in Israel. Leonard was a bit apprehensive about going on stage. Finally, we were walking through the barrier to the platform and he said ‘I can’t do it. I need a shave.’ So he shaves and all the other guys in the group shave. ‘I’m ready. Let’s go.’ Half way to the microphone he turns around and says, ‘I missed a spot.’

“The crowd was getting restless and there was a little note tacked to the microphone and it said ‘Dear Leonard. Please hurry up and get your s____ together.’ Leonard returned and sat on stage as the audience sang this Israelian song, which he accepted as a gift.

“I always dreamed as a high school student that art could be lived as well as performed. Leonard approached each moment as an act to be shaped. His life is an art form. It was a reaffirmation of my dreams to be around an ordinary situation with him and more important to me than the theatrical ones,” disclosed Warnes in our conversation for the periodical.

In February 1987, Jennifer Warnes released her sixth studio album, Famous Blue Raincoat: The Songs of Leonard Cohen, she produced with C. Roscoe Beck. It housed a version of “Bird On the Wire.” The collection jumped-started Cohen’s global radio airplay, live bookings and retail awareness.

“My tunes often deal with a moral crisis,” Leonard Cohen divulged in our 1976 Melody Maker interview. “I often feel myself a part of such a crisis and try to relate it in song. There’s a line in a poem I wrote that sums this up perfectly: ‘My betrayals are so fresh they still come with explanations.’

“In the early days I was trained as a poet by reading in English, poets like Lorca and Brecht, and by the invigorating exchange between other writers in Montreal at the time.

“As far as the use of Biblical characters in such tunes as ‘Story Of Isaac,’ and ‘Joan Of Arc,’ it was not a matter of choice. These are the books that were placed in my hand when I was developing my literary tastes.”

Cohen’s “Story of Isaac” has been recorded by Judy Collins, Suzanne Vega, Patrick Ovenden, Linda Thompson and Roy Buchanan.

“When Songs From A Room came out it would prove to the world that Songs Of Leonard Cohen and ‘Suzanne’ were no flukes and sealed my conviction that here was an artist who had something to say,” offered Prof. Robert Inchausti, a Professor of English at Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo and author of five books.

“Cohen was now in the record-shop bins under his own name,” reinforced Inchausti. “He also reached us through the radio for the first time. Leonard gets through the door to the FM airwaves on progressive and underground outlets like KZAP-FM in Sacramento, KSAN-FM in San Francisco, and Pacifica stations like WBAI-FM in New York, or the affiliates in Berkeley and Los Angeles.

“The arrival of Cohen’s debut album and Songs From A Room also coincides with the expanding record business. The Tower Records chain was started by Russell Solomon in 1960 in Sacramento, where I lived. In late 1967, a Tower branch opened in San Francisco. Record shops became record stores. Plus there was now a new breed of late-night radio deejays and music journalists eager to expose us to Cohen and other important new recording artists.

“And in my conversations with my friends, Cohen seemed older than the other rock guys. Like somebody you could grow up and be like. And have women and be a mystic and hang with real hip people. Cohen was a rock guy not a folkie. As a counterculture figure he always seemed to be at some point that was near the center of the whole thing. That was kind of religious and mystical in a way that seemed more true to me than the political. He never spoke like a guru or anything. It was always with this incredible humor, irony.”

“In the summer of 1967, some of Cohen’s poetry collections had made their way to book and underground head shops in America, and hipper university professors assigned Beautiful Losers in modern literature classes,” recalled poet Dr. James Cushing, a KEBF-FM deejay and English and Literary Professor at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo.

“By December 1967, with Songs of Leonard Cohen, we could hear him sing some of his poems, like ‘Suzanne,’ or lyrics that were crafted for songs. During spring 1969 Cohen delivered Songs From A Room.

“Remember, he did not make his first LP until he was thirty-three years old. Like Howlin’ Wolf, who first recorded at age forty-one, Leonard Cohen was not an adult offering supervision, but an adult giving us permission.”

“Songs From A Room may be Cohen goin’ country, the echoes of George Jones and Hank Williams crowding his inner ear, with the heartache of poor white folks transformed into jubilation,” concluded author Kenneth Kubernik. “But there is no escaping the emotionally fraught cast of characters who constitute Cohen’s blighted universe, his bloodhound delivery sagging under the weight of the forever forlorn.

“The songs, unlike the timeless country formulation, offer no liberating exits for his subjects, let alone the listener. There are no lessons learned, no redemption for the philanderer, the wastrel or the woman of constant sorrow. Cohen remained a steadfast haut bourgeois; his themes of political and personal betrayal, Old Testament judgment and the pitilessness with which we treat each other are tropes that reflect his deeply cosmopolitan view of the world. Cohen’s songs are daunting, and to the suggestive mind their appeal is mesmeric.”

Columbia Records, meanwhile, was itching to get a return on its investment—which meant touring, a fact of pop-star life that rankled at even this most inveterate of travelers. Cohen turned to Bob Johnston to arrange a band, manage the tour, and provide a comfort zone from which he could keep the terrors of stage fright at bay.

“I liked the work Bob did with Dylan and we became good friends,” Leonard underlined in our 1976 interview. “Without his support I don’t think I’d ever gain the courage to go and perform. He played harmonica, guitar and organ on tours with me. He’s a great friend and a great support. We worked hard on the albums we did together, but I wasn’t totally happy. Overall I couldn’t find the tone I wanted. There were some nice things, though. With each record I became progressively discouraged, although I was improving as a performer.”

(Harvey Kubernik in 2014 wrote a critically acclaimed biography Leonard Cohen Everybody Knows now published in six foreign language editions.

His encounters, interviews, recording sessions and interactions with Leonard Cohen over the last half century are chronicled in a multi-voice narrative Leonard Cohen: Agency of Yes now displayed on the official Leonard Cohen Forum at http://www.leonardcohenfiles.com/kubernik2017.pdf

Kubernik is an award winning author of 15 books. His literary music anthology Inside Cave Hollywood: The Harvey Kubernik Music InnerViews and InterViews Collection Vol. 1, was published in December 2017, by Cave Hollywood. Kubernik’s The Doors Summer’s Gone was published by Other World Cottage Industries in February 2018.

During November 2018, Sterling/Barnes and Noble published Kubernik’s The Story of The Band From Big Pink to the Last Waltz.

Harvey Kubernik penned the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special and The Ramones’ End of the Century.

In November 2006, Harvey Kubernik was a featured speaker discussing audiotape preservation and archiving at special hearings called by The Library of Congress and held in Hollywood, California. Harvey musical and literary expeditions are displayed on www.otherworldcottageindustries.com.