By Harvey Kubernik © 2017

Leonard Cohen, the Canadian songwriter/ poet/novelist and performer waived a physical goodbye at age 82 on November 7, 2016, just after the release of his 14th album, the uncompromising and urgent You Want It Darker.

In December 2016 I was invited to guest deejay on Los Angeles radio station The Sound 100.3 FM Classic Rock KWSD My Turn program. KWSD is Southern California’s classic rock station with over 1.3 million listeners.

The broadcast aired in January 2017. The studio overlooked the street in the mid-Wilshire district area where Leonard lived in a duplex. I dedicated “Hallelujah” to him.

It was my audio service of sitting shiva for Leonard.

November 7, 2017 will be the one year yahrzeit of his death.

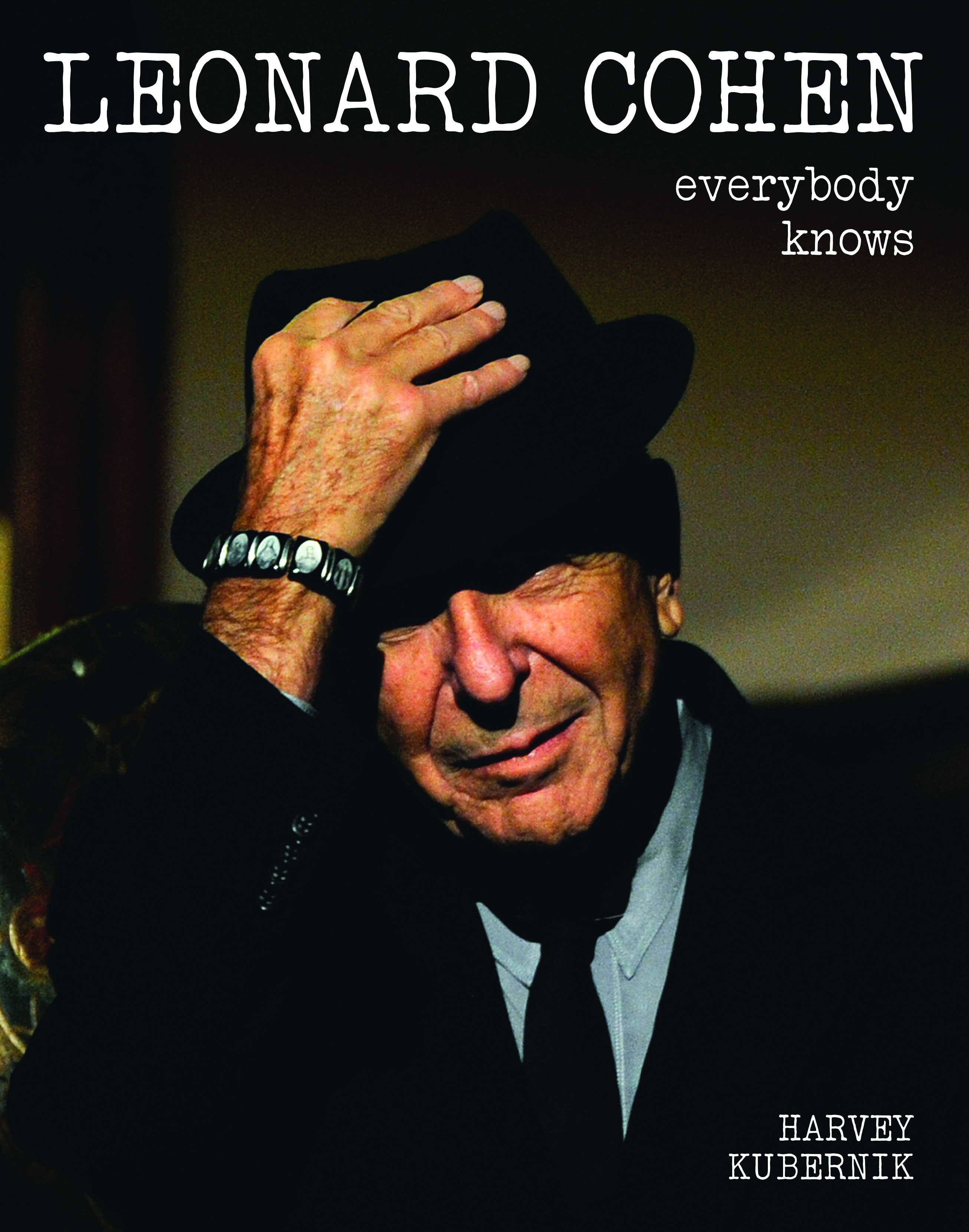

My 2014 critically acclaimed book on Leonard Cohen, Everybody Knows, is now published in America, England, Russia, France, Germany, China and two different editions in Canada. It’s now out in paperback in the UK from Omnibus Press.

I’ve also been cited and quoted, and my archives utilized in four earlier books on Cohen by authors Ira Nadel, Anthony Reynolds, Sylvie Simmons and Liel Leibowitz. I recorded with Leonard and several Wrecking Crew veterans, including Cave Hollywood’s owner, guitarist David Kessel in 1976 and ’77 (handclaps and percussion), along with being the food runner, on Leonard’s Phil Spector-produced Death of a Ladies Man album.

I’ve also been cited and quoted, and my archives utilized in four earlier books on Cohen by authors Ira Nadel, Anthony Reynolds, Sylvie Simmons and Liel Leibowitz. I recorded with Leonard and several Wrecking Crew veterans, including Cave Hollywood’s owner, guitarist David Kessel in 1976 and ’77 (handclaps and percussion), along with being the food runner, on Leonard’s Phil Spector-produced Death of a Ladies Man album.

Long before the current century Leonard Cohen retail and media renaissance, an interview I conducted with Leonard in 1975 for Melody Maker was published again in the spring 2017 first collection of essays on Cohen in the U.K. by Cambridge Scholars Publishing in the book Spirituality and Desire in Leonard Cohen’s Songs and Poems: Visions from the Tower of Song, edited by Peter Billingham.

The family of Leonard Cohen will be inviting fans from around the world to join them, along with renowned musicians, the Prime Minister of Canada and the Premier of Quebec in celebrating Cohen’s legacy for Tower of Song: A Memorial Tribute to Leonard Cohen at the Bell Centre in Montreal on Nov. 6, 2017.

Participating artists include Elvis Costello, Lana Del Rey, Feist, Philip Glass, k.d. lang, The Lumineers’ Wesley Schultz and Jeremiah Fraites, Damien Rice, Sting, Patrick Watson, and Adam Cohen, who is also co-producing the event.

Additional artists, as well as actors paying homage through spoken word performances, will be announced soon.

“My father left me with a list of instructions before he passed: ‘Put me in a pine box next to my mother and father. Have a small memorial for close friends and family in Los Angeles…and if you want a public event do it in Montreal,’” said singer-songwriter Adam Cohen “I see this concert as a fulfillment of my duties to my father that we gather in Montreal to ring the bells that still can ring.”

The event will benefit the Canada Council for the Arts, the Council of Arts and Letters of Quebec, and the Montreal Arts Council.

“Proceeds from the event will be shared by several of Canada’s arts organizations in an effort to continue the legacy of great works,” said Robert Kory and Michelle Rice, Leonard’s managers. “In fact, Leonard often mentioned the Arts Councils, whom he credited as providing essential support in the early days of his career.”

Tower of Song will mark the first anniversary of Leonard’s passing and commence a week of celebrations honoring Cohen in Montreal. As previously announced, the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal’s new exhibit, “Leonard Cohen: Une brèche en toute chose / A Crack in Everything,” will open to the public November 9.

The exhibit was approved by the late songwriter before his passing and will celebrate Cohen’s life and work. For more information, please visit www.LeonardCohen.com

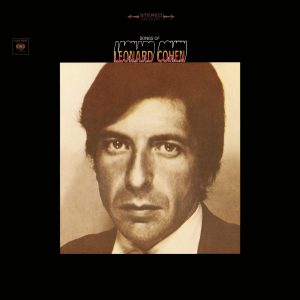

I thought it was appropriate to write a memoir tribute to Cohen and examine the 50th anniversary of his debut album, Songs of Leonard Cohen, released in December 1967.

This past July, I gave a lecture and Q. and A. audience session at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s Author Series in Cleveland, Ohio, to promote my book 1967 A Complete Rock Music History of the Summer of Love (Sterling Publishing) and my Cohen Everybody Knows book, (Palazzo Editions), it felt logical to remind the world once again of Leonard’s legacy and Songs of Leonard Cohen. In 2008 Cohen was inducted into the prestigious facility by Lou Reed.

This past July, I gave a lecture and Q. and A. audience session at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s Author Series in Cleveland, Ohio, to promote my book 1967 A Complete Rock Music History of the Summer of Love (Sterling Publishing) and my Cohen Everybody Knows book, (Palazzo Editions), it felt logical to remind the world once again of Leonard’s legacy and Songs of Leonard Cohen. In 2008 Cohen was inducted into the prestigious facility by Lou Reed.

Over the last decade the museum has had several Cohen items on exhibit, including handwritten lyrics to “First We Take Manhattan,” “Democracy,” “If It Be Your Will,” the handwritten score to “Hallelujah” and handwritten set list to Cohen’s landmark appearance on Austin City Limits TV series.

On June 10, 2017 a stone bench dedicated to the memory of Leonard was inaugurated on the Greek island of Hydra. On the same day the Municipality of Hydra named a street after Leonard.

During the summer of 2014, webmasters Jarkko Arjatsalo (Finland) and Marie Mazur (USA) of The Leonard Cohen Forum introduced a fundraising campaign to celebrate Leonard Cohen’s 80th birthday.

Donations were received from 366 members from all over the world. After an online discussion, Forum members decided to create something lasting: a stone bench on the Greek island of Hydra, where Leonard wrote his novels and many poems and songs.

The bench was designed by Greek architect George Xydis, following the local traditional style. It took time almost three years to get the final permission from the Historical Office in Athens.

The bench was finally built by the Municipality of Hydra in June 2017 and inaugurated during the Forum Meet-up on the island. The bench was dedicated to the memory of Leonard.

The bench was inaugurated by George Koukoudakis (Mayor of Hydra), Lakis Christidis (Hydra Cinema Club) and Jarkko Arjatsalo (The Leonard Cohen Forum).

Cohen had been aware of the project since September 21, 2014. His touching reply at that time was read by Jarkko Arjatsalo during the bench inauguration.

In an email, Leonard wrote:

THE BENCH:

I read every name.

I bow my head in gratitude.

DEAR FRIENDS

Thank you for the countless times you have lifted my spirit.

Thank you for the comfort and the encouragement.

Love and Blessings,

Leonard

The bench was built through the united efforts of the Municipality (the legal owner of the bench), The Leonard Cohen Forum (fundraising) and The Cinema Club of Hydra (coordinator). The bench is located on the road from Hydra City to Kamini.

The remaining money collected during the fundraising campaign will be donated to charity and social projects on Hydra.

This past August at the 2017 MTV Video Music Awards, actor and musician, Jared Leto, of 30 Seconds to Mars fame, remembered the late Chris Cornell, former lead singer of Soundgarden, and the late Chester Bennington, former lead singer of Linkin Park, who both died by suicide during the summer of 2017. Leto mentioned that Bennington sang a cover of “Hallelujah” at Cornell’s funeral.

In August I was the guest speaker at the Stephen Wise Temple in Bel-Air, California celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Summer of Love. The Shabbat service was followed by a concert featuring music from 1967 performed by the Stephen Wise clergy and musicians, including vocalists Freda “Band of Gold” Payne and Florence LaRue of the wonderful 5th Dimension. I helped narrate the stage program culled from my 1967 book. After the event, I must have answered a dozen questions about Leonard Cohen and my book.

My own 50 year relationship to Leonard’s words and music literally flashed in front of me.

It was in December 1967 when I first discovered Leonard Cohen in California on Pasadena-based KPPC-FM when a late-night deejay spun an advance acetate copy of Songs of Leonard Cohen and spotlighted “Suzanne.”

At U2’s June 23rd Toronto show, Bono acknowledged Cohen singing a verse of “Suzanne” during their performance of “Bad” while adding, “[Leonard Cohen] is an addiction I’m not ready to give up”

By 2017, 2,600 covers of the song have been recorded of Leonard’s tune, including Noel Harrison, Jack Jones, the Sandpipers, Nina Simone, Roberta Flack, Neil Diamond, Spanky & Our Gang, Harry Belafonte, Joan Baez, Gary McFarland, Aretha Franklin, Tangerine Dream, Francoise Hardy, Diane Reeves, Peter Gabriel, Pearls Before Swine, and Nana Mouskouri.

In December 1974, a Columbia Records publicist arranged an interview with Leonard and I at the Continental Hyatt House in Hollywood. Cohen was in the midst of a multi-night engagement at Doug Weston’s Troubadour in West Hollywood. One evening I was there with Justin Pierce and Sharon Weiss, later to become Leonard’s publicist during 1988-1993. Bob Dylan and Phil Spector sat at a table next to us.

The following afternoon I conducted my first interview with Leonard for Melody Maker.

“In the early days I was trained as a poet by reading in English, poets like Lorca and Brecht, and by the invigorating exchange between other writers in Montreal at the time.

“My tunes often deal with a moral crisis. I often feel myself a part of such a crisis and try to relate it in song. There’s a line in a poem I wrote that sums this up perfectly: ‘My betrayals are so fresh they still come with explanations.’ As far as the use of Biblical characters in such tunes as ‘Story Of Issac,’ and ‘Joan Of Arc,’ it was not a matter of choice. These are the books that were placed in my hand when I was developing my literary tastes.”

Over the past few decades I queried several associates, friends, deejays, professors, writers, poets, and musicians about the work and ongoing artistic impact of Leonard Cohen.

Larry LeBlanc: For 50 years, over 14 albums, 9 volumes of poetry, and two novels, Leonard Cohen– poet, novelist, troubadour, songwriter, spiritual tourist, social provocateur, and ladies’ man—has shared his romantic vision.

“It’s been good honest work.

“A major writer of the English language, Leonard– inducted into the Juno Hall of Fame in 1991– gives importance and dignity to songwriting. His songs are discussed, analyzed, agonized over and made love to the world over.

“Leonard started playing guitar at summer camp in 1950. He wasn’t attracted to the instrument so much as for a musical reason. He used it as a courting tool. But he also thought one day he’d become a singer, however. He used to stand and sing in front of the mirror to see how he looked.

“At McGill University, he began writing poetry, and formed the country and western trio, the Buckskin Boys. He also worked in a nightclub above Dunn’s deli called Birdland. He’d read poems or improvise them while Maury Kaye and his bebop group played.

“After he dropped out of a Master’s program at Columbia University in New York Leonard obtained a grant, and was able to travel through Europe. He eventually settled on Hydra, staying on and off for seven years. He wrote two more collections of poetry, Flowers For Hitler (1964) and Parasites of Heaven (1966) there; and the novels, The Favorite Game (1963), and Beautiful Losers (1966).

“As he finished Beautiful Losers, he realized he was full of music (if only because he’d written the book to the accompaniment of the American Armed Forces radio service). He decided to go to Nashville, and become a country songwriter. On his way there, he met Toronto-born manager Mary Martin who persuaded him to stay in New York.

“In 1967, Leonard played 15-20 concerts, including the Newport Folk Festival where he stole the audience cheers from established stars with the Mariposa Folk Festival in Toronto; and two concerts with Judy Collins who recorded ‘Suzanne’ and ‘Dress Rehearsal Rag’ on her 1966 album, In My Life.

“A few months after Newport, Columbia Records released his debut album, The Songs of Leonard Cohen. It had such signature Cohen songs as ‘Suzanne,’ ‘Hey, That’s No Way To Say Goodbye,’ ‘So Long, Marianne,’ and ‘Sisters of Mercy.’”

Andrew Loog Oldham: Leonard wrote songs because he had to, and because he wanted to get laid. Later he wrote songs because he wanted to get paid. That’s when I decided he had something to say.

“In 1988 with I’m Your Man he put the sex into electronic music with wit and verve and he still turned corners with his songs. Goodbye baby and amen with thanks for all you gave us in that exampled, dignified, laconic way.”

Dr. James Cushing: By the summer of 1967, some of Cohen’s poetry collections had made their way to book and underground head shops in America, and hipper university professors assigned Beautiful Losers in modern literature classes.”

“Remember, he did not make this LP until he was 33 years old. Like Howlin’ Wolf, who first recorded at age 41, Leonard Cohen was not an adult offering supervision, but an adult giving us permission. I first heard Cohen on KPPC-FM in Southern California.

“In 2016, those of us lucky enough to have seen Cohen in concert became even luckier, but sadder, as lucky people often are. It was a dark year, filled with farewells. Leonard Cohen’s exit was neither the most shocking nor the most painful. His body was old and full of days. His songs had long been varying the theme of Farewell, and in his last tours, every concert felt like a valediction. But in 2017, his absence (for me, anyway) has become an empty space as large as the ones Bowie or Prince left behind. You Want It Darker, which illuminates that empty space, is actually much in the same spirit of Bowie’s Blackstar: a sublime farewell, but from a different tradition. Only Cohen could fuse an authentic Jewish melancholy with the elaborate merriment of European art-song and the ghost-whisper cleanliness of digital synthesizers.

“Cohen’s career now enters its fourth phase, After the End — the phase that Cohen’s colleagues Allen Ginsberg, Irving Layton, Jimi Hendrix, and Janis Joplin have been in for decades. Is there “previously unreleased material,” written, recorded, and/or filmed? Let us hope so. Let us also hope that university literature departments will devote more attention to Cohen’s poems and novels especially 1966’s Beautiful Losers. For me, this lyrical dream-novel of friendship and loss outdoes Kerouac’s On the Road for its joy, compassion, and vivid sense of the sacred.”

Tosh Berman: Strange enough I know very little of Leonard Cohen’s work. I have heard

his classic albums -especially the first one, but never actually owned the damn album! Without a doubt a great songwriter, etc but never had the full on passion for his work (yet). Working at Book Soup, his books were always in demand. At the time I was working at the Soup we always had to keep his novel Beautiful Losers in stock as well as a collection of his lyrics and

poetry. There is really not that many artists like him that is out there making music or touring.

“There used to be a coffee shop/diner at the strip mall on Santa Monica and La Brea, and I totally forgot the name of the place, but it was reported to be David Lynch’s favorite coffee shop. Anyway I remember having a late breakfast one day there, and noticing a very beautiful woman at the counter, and she was with Cohen. It stayed in my mind because I thought ‘why is this beautiful young girl with this much older man?’ Then at that moment I recognized Leonard and thought ‘of course!’”

Leonard Cohen has never been a stranger to music. As early as 1954, he was playing country music at square dances in a group called the Buckskin Boys.

In an interview I published in Melody Maker in 1975, jointly conducted with writer Justin Pierce, Cohen told us at the Continental Hyatt House on Sunset Strip, “I don’t have any reservations about anything I do. I always played music. When I was 17, I was in a country music group called the Buckskin Boys. Writing songs came later, after music. I put my guitar away for a few years, but I always made up songs. I never wanted my work to get too far away from music. Ezra Pound said something very interesting, ‘When poetry strays too far from music, it atrophies. When music strays too far from the dance it atrophies.”

In 1966 Cohen relocated to the U.S. and a return to songwriting, after penning two novels, including the maligned and praised Beautiful Losers, and four books of poetry.

“I came to New York and was unaware of what was going on at the time,” Cohen told me in 1975. “I had never heard of Phil Ochs, Bob Dylan, Judy Collins or any of these people, and I was delighted, overwhelmed and surprised to discover this very frantic musical activity.”

Mary Martin, Cohen’s manager, hounded the legendary Columbia Records staff producer and A&R man, John Hammond Sr., sending him Leonard’s books, urging him to view the 1965 Don Owen and Donald Brittain acclaimed documentary, “Ladies and Gentlemen…Mr. Leonard Cohen. ” She personally delivered Cohen’s demonstration tape (recorded in her bathtub on a Uher Werke reel-to-reel!) to the talent scout.

Duly impressed, Hammond telephoned Cohen to meet and hear songs at the Chelsea Hotel, after they met for lunch.

Hammond had become further aware of his abilities from Judy Collins’ recent cover version of “Suzanne.”

“Hammond was extremely hospitable and decent,” remembered Leonard. “He took me out for lunch at a place called White’s on 23rd Street. It was a very pleasant lunch, and he said, ‘Let’s go back to your hotel room, and maybe you can play me some songs.’

“So he sat in a chair and I played him a dozen songs. He seemed happy and said that he had to consult with his colleagues but that he’d like to offer me a contract.”

Like Billie Holiday, Count Basie, Aretha Franklin and Bob Dylan before him, Leonard Cohen was about to join Hammond at Columbia Records, who subsequently received the approval from new label head Clive Davis to sign Cohen to a recording agreement.

In May, Songs of Leonard Cohen began in Studio E. on East Fifty-Second Street with Hammond himself at the helm. He brought with him the noted jazz bassist, Willie Ruff, a veteran of stints with Dizzy Gillespie, Louis Armstrong, and Count Basie, to provide ballast to Cohen’s twitchy guitar musings. Jimmy Lovelace is the drummer on “So Long, Marianne.”

John Simon: John Hammond, (also a class act), would schedule a session then cancel and reschedule a month late – which drove Leonard crazy, staying at the Chelsea Hotel. So they assigned him to me. We went to my folks’ house in Connecticut (they were away), to go over material. Leonard stayed up all night going through my dad’s library. I slept. He didn’t. He was a man, while the other rock acts I worked with were boys. He was an established poet. Real bright and clever with words. And he had that finger-picking triplet style that was very impressive. Sort of a classical technique.

“I’m proud of the experimentation I did use wordless women’s voices instead of instruments, mostly Nancy Priddy, my girlfriend at the time. About the chorus in ‘So Long, Marianne,’ I guess it was the logical step to try adding words after we’d done the wordless thing. I’m an arranger not an engineer.

“The engineer, Fred Catero, with an A – a wonderful guy. I mixed my first hit with Fred, the Cyrkle’s ‘Red Rubber Ball.’”

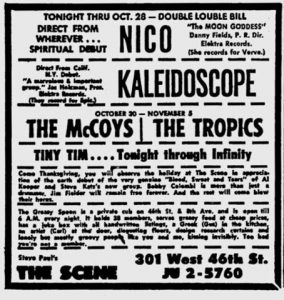

On October 27th, near the end of his recording sessions, Leonard Cohen headed over to Steve Paul’s The Scene at 301 W. 46th Street in New York to monitor Nico who was headlining, promoting her new album, Chelsea Girls. Opening was the West Coast-based, Kaleidoscope, making their New York debut.

Chris Darrow: The host for the club was Tiny Tim, who announced all the acts and would play a song or two as well. We were opening for Nico, who I had met in LA, and she was playing as a solo act…. just her and a Hammond B3 organ.

“The Opening night was very crowded and Frank Zappa and members of the Mothers of Invention showed up to show their support.

“That night, Leonard Cohen came up to me in the bar light. He was the palest guy I had ever seen he almost seemed to glow. He was wearing a black leather suit coat and carrying a black leather briefcase. Leonard loved our band and was wondering if we would be interested in playing on his forthcoming album. I didn’t know who he was at the time and told him to talk with our managers who were at the bar.

“The next day, Solomon Feldhouse, David Lindley, Chester Crill, and I were in his apartment, trying to play some of his songs. He was having trouble finding musicians that could play his stuff. Since he wasn’t a great guitar player. His guitar playing was minimal at best it was hard for some people to figure his music out.

“Cohen gave us the impression that he was having trouble finding the right sounds for a few of his compositions. He seemed happy when we were able to come up with some solutions to his musical needs.

“The producer Bob Johnston was there. I ended up playing my rare, 1950’s Premier Bass and my 1921, Gibson F-4 mandolin on ‘So Long, Marianne’ and bass on ‘Teachers.’ The slow build of ‘So Long, Marianne’ is one of the secrets of its success and, at 5:39 seconds long, it has a hypnotic, repetitive groove that sustains itself through the entire song. The twin, acoustic guitars, playing two separate time signatures, creates a smooth bed for the lyrics to lie on. The mandolin part comes in at just over 3 minutes and knocks the song up a notch and adds a different tonality that is not expected. The memorable chorus gets slightly more powerful each time it repeats and brings the song all together at the climax.

“‘Teachers’ is a darker, minor key song, that uses one of Solomon’s middle eastern instruments, the Caz, and Chester and David’s twin fiddles, to give it a very exotic, international flavor. Once again, the there is a rather insistent rhythmic feel to the song, which counters perfectly with the ethnic sounds.

“There were no credits on the ensuing record, so not many people are aware of our inclusion in it. We were on Epic Records, a division of Columbia, so I could never figure out why we weren’t listed.”

From mid-May to through November in 1967, Cohen had done 25 tunes with Hammond and John Simon and some sessions with Bob Johnston in three Columbia studio rooms.

“My first producer was John Hammond and I didn’t know the ropes at all,” admitted Leonard in a 1976 interview we did for Melody Maker.

“We recorded some numbers, and then his wife got sick and he became ill. Then I switched producers to John Simon, whom John Hammond suggested.

“I put the tracks down with guitar and voice, and used a bass sometimes. Simon took them and worked on them, and he presented me with the finished record, but I felt there were some eccentricities in his arrangements that I objected to. John Simon was great, and much greater than I understood at the time.”

Cohen was very grateful for the instrumental input from Kaleidoscope and recorded in his journal of the time, “The Kaleidoscope delivered me. Stu [Eisen], Solomon, David, Chester, Chris, John. May I bless them as they have blessed me.”

Clive Davis: I was really just getting my feet wet. I was in the business side of it for a year. I was working with Andy Williams, the young Barbra Streisand and Bob Dylan, and signed Donovan to Epic in 1966. I was observing. When you get a title of President, before you start making active moves, you sort of appraise the situation. Columbia at the time was prominent in the field of classical music and Broadway, middle of the road music, coming out of the Mitch Miller era, with artists like Tony Bennett, Streisand, and Andy Williams, among others. I was seeing the business change.

“There was certainly some evidence of rock ‘n’ roll, clearly the Beatles had arrived, (Elvis) Presley. The only rock that Columbia was in was more of Bob Dylan as a writer, with some of his hits being popularized by Peter, Paul & Mary, and the Byrds.

“I was seeing music change, but I was waiting for the A&R staff to lead into these changes that were showing evidence in becoming important in music.

“In June I really came to the Monterey International Pop Festival not knowing what to expect, but seeing a revolution before my eyes. I was very aware that contemporary music was changing. The success of the artists I signed at Monterey gave me confidence that I had good ears. It gave me the confidence to trust my own instincts.”

Al Kooper: By late 1967 I was a staff producer at Columbia Records. Leonard Cohen, signed by John Hammond, and then John Simon is the producer and they walked into this new climate at the Columbia label. John did the Blood, Sweat & Tears album. That LP and Cohen’s first record also share the same engineer, Fred Catero.

“As far as Columbia Records in England, they understood what was being done from the label in America in 1967 and ’68. Bookends, Dylan’s John Wesley Harding, Songs of Leonard Cohen, the BS&T Child Is the Father to The Man album that I signed single-handedly to the label by Clive Davis. They called it ‘The ‘Rock Machine.’ That was a result mostly of the English music press and not the domestic label. The label had a real grasp on the music that was being made. FM radio was a factor.”

Fred Catero: Leonard Cohen came to the Columbia label from John Hammond and also on the heels of the June 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival. The arrival of FM radio in 1967 didn’t change Columbia Records but the demographics of FM radio changed the label and who was listening. Because FM is ideal for high fidelity. It was much more clearer so you could hear the subtleties of his voice.

“We as a human organism rely a lot on the subtleties and FM was able to transmit that. Especially if you were listening on head phones or a good system. Whereas AM was limited in its ability to transmit that feel. And, at the time, an older group. Leonard Cohen wouldn’t have worked being introduced on AM radio in 1966 or ’67.”

Songs of Leonard Cohen shipped to the record racks and bins the last week of 1967. “Suzanne” quickly garnered radio airplay. It soon became a staple on the FM dial and always remained in Cohen’s stage repertoire.

Peter Lewis: I first got turned on to Leonard Cohen in New York. It must have been 68′ or 69′ when my marriage was falling apart. We [Moby Grape] were playing the Fillmore East or Village Theatre. When the set was over I remember meeting Linda Eastman backstage. She was there with her camera to take pictures of the band.

“I think she saw how downright lonely I was. She was one of those rare creatures you meet sometimes in life who just “knows” what to do and took pity on me. When we got to her apartment that night she went to her turntable and put on Leonard’s first record. Of course ‘Susanne,’ ‘That’s No Way to Say Goodbye’ etc. came to me like the soundtrack of my life at the time.

“Later, Bob Johnson produced our last album for Columbia Truly Fine Citizen, in Nashville. When the record was finished he asked me if I wanted to stay after the others went home. He said he liked my voice and wanted to introduce me to Johnny Cash, Bob Dylan, and Leonard Cohen.

“Why did I go home with the others and not take my shot at the time? It may have been some crazy idea that Many Grape wasn’t finished yet.

“Anyway, I never stopped listening to and admiring Leonard Cohen. He was the first artist I became fully conscious of, after Dylan, who could make the music fit the lyrics in a way that seemed already familiar. Anyway it all started that night at Linda’s. Leonard’s songs sounded to me like I’d heard them before in a dream, even as I sat there listening to them for the first time.”

Marina Muhlfriedel: Although I had heard the album before, this is my first true contemplation of the Songs of Leonard Cohen. I am alone, sprawled on the floor of the library in my parents’ home in West Los Angeles. A sketchbook of drawings and poems I nearly always have on hand is beside me. I close my eyes as the songs play again and again and I sink into a world of street-weary strangers and seducers, of shadowy alleyways and perfumed boudoirs that double as sacred shrines. I mull them like secrets. In my own small way, I vow to always pray for the angels and to someday offer Chinese tea and oranges to a melancholy lover. And I sense that melancholy, angels, love, loss and passion are but intersecting creases on Leonard Cohen’s palm as he moves through a world that’s unfathomably bigger and more interesting than my own.

“His depth, his wisdom and implied sacraments transport me. He is at once a psalmist and a love-ravaged romantic. I am envious of the women he pines for. I am jealous of his perfect words. The songs are slow and authoritative, nary a wasted syllable or indulgent frivolity. In my sketchbook, I try to hone one of my adolescent poems to emulate Cohen’s precision. Believing, in some abstruse way, the gravel-voiced poet is my teacher—a loner with a guitar and an elixir of dreams at a train station on the outskirts of town. I cross out a few words turn the album over again and close my eyes.”

On February 22, 1967, Leonard was recruited by Judy Collins to join her, Pete Seeger and Tom Paxton at a benefit show to support the radio station, WBAI-FM, at the Village Theatre in New York.

Before a gathering of 3,000, Cohen stammered through a few verses of “Suzanne” before retreating behind the curtain, gripped by fear. Collins gently coaxed him back on stage. They concluded the song as a duet.

Considering how comfortably and mindful he’d performed at numerous poetry readings in Canada before equally large and attentive crowds, it was significant that the act of singing his words brought about this paralyzing effect.

By 1970 Leonard would eventually emerge as a highly competent singer, songwriter and story teller in concert situations. I asked Cohen in a 1976 Melody Maker conversation about his Live Songs LP and recent bookings as a memorable live attraction.

“I used to be petrified with the idea of going on the road and presenting my work,” confessed Leonard. “I often felt that the risks of humiliation were too wide. But with the help of my last producer, Bob Johnston, I gained the self-confidence I felt was necessary.

“I liked the work he did with Dylan and we became good friends. Without his support I don’t think I’d ever gain the courage to go and perform. He played harmonica, guitar and organ on tours with me. He’s a great friend and a great support. We worked hard on the albums we did together.

“My music now is much more highly refined. When you are again in touch with yourself and you feel a certain sense of health, you feel somehow that the prison bars are lifted, and you start hearing new possibilities in your work.

The previous album Live Songs represented a very confused and directionless time. The thing I like about it is that it documents this phase very clearly.”

Bob Johnston: I put his 1970 band together. I told Leonard I’d get him the best musicians in the world. And he replied, ‘Bob. I don’t want the best musicians in the world. I want friends of yours.’ I said, ‘Good enough.’ I played organ and piano.

“I always ask the artist ‘what do you want to do?’ You get better performances when you make the artist comfortable.”

You want celluloid proof of Cohen’s stage craft?

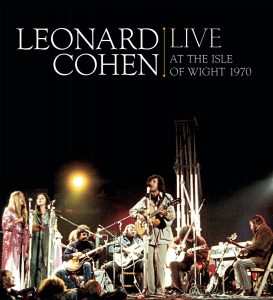

Over 47 ago on August 31, 1970, Leonard Cohen, then age 35, was ushered onstage during the Isle of Wight music festival on a small island off the southern coast of England.

He was billed with Miles Davis, Joni Mitchell, the Who, the Doors, the Moody Blues, Jethro Tull and Jimi Hendrix. The crowd, alas, had its own agenda, metastasizing into a heaving, barreling beast, crushing the gates and fences, rubbishing the prim seaside community.

The throng numbered 600,000 and Cohen was at the epicenter of the event which now had fire and smoke encroaching structures and equipment.

When Cohen and his band, which included Bob Johnston and Charlie Daniels, finally took to the stage, it was two o’clock in the morning.

Kenneth Kubernik: The punters, restless in the aftermath of Jimi Hendrix’s incendiary performance, were instantly tamed by this unkempt, unprepossessing gentleman, adorned in pajama bottoms (he’d been having a nap backstage and barely answered the bell to perform). As poised as Caesar before his legions, Cohen took command of his ‘Army’ – his group’s nickname – and held the half million attendees in thrall.

“Documentarian Murray Lerner captured it all on film. The resulting 2009 DVD – Leonard Cohen Live at the Isle of Wight – 1970 – demonstrated his gift for conjuring magic out of mayhem. The oft-derided listless baritone voice, the plodding rhythms and the deathly pallor of the lyrics conspired to produce a hypnotic calm.”

Cohen’s recital was taped by Columbia Records staff A&R producer and engineer Teo Macero who supervised the live audio recording.

Murray Lerner: I first heard Cohen as a literary character, a poet. And then in the late sixties a couple of his records on the radio. He came out acoustic and walked out with guitar.

“I felt hypnotized. I felt his poetry was that way. I was really into poetry and that is what excited me about him.

“When he did ‘Suzanne’ he said, ‘Maybe this is good music to make love to.’ He’s very smart. He’s very shrewd. The other thing he was able to do, the talking, I think the audience was able to listen to him. They heard him and felt he was echoing something they felt. The audience and I were mesmerized. It was incredible and captivating. That night, Leonard was on some sort of mission.

“I thought the Isle of Wight 1970 and the Cohen footage had touched the deep chord of people. I realized how deep it was and I was startled how prophetic it was. I was proud and excited at what I had done.”

Charlie Daniels: “One thing that needs to be said about Bob Johnston and bringing people to town like Al Kooper, Bob Dylan and then Leonard Cohen. There was skepticism about Bob coming to Nashville because he was taking the place of a legendary producer, Don Law, who was an institution in town.

“Here’s this guy Johnston from New York, who had been doing Simon & Garfunkel, Dylan, and Leonard Cohen, who were not really thought of as being country. But the first thing Bob did when he came to town was to do a number one song with Marty Robbins!

“And in ‘67 and ’68 Bob produced the albums John Wesley Harding and Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison. Bob had gained credibility. He was also at the same time, bringing Dylan and Leonard Cohen into town who had never lived here.

“Dylan recorded in Nashville in 1966 for a while, but it was he’d come to town, do his stuff, and leave. Dylan happened to record in a studio in Nashville and worked in it. Forget that when Leonard came to Nashville. He lived out in the country for a while. He spoke a different way than everybody else around there did. But he had a great sense of communicating with people. I knew all the musicians on Leonard’s album.

“And, hassles with long hairs, prejudice, racism, didn’t exist in our world. Now it has not always been that way. I was raised in a very prejudice time.

“I mean I’m 76 years old and was raised in the South during the Jim Crow days. I never went to school with a black person or a Jewish person. I mean, it was not a place of my making. It was a place I had to live in. And I had to come to understand on my own what was going on and to get away from it. And to look back on it and say this is wrong. This is not right, you know.

“In the sixties everything was pretty much in the throes of a lot of upheaval. This was back in Martin Luther King, Jr.’s salad days, when he was going around, doing things that a lot of people didn’t understand it or didn’t get it. I was in Nashville when Dr. King was assassinated in Memphis.

“The thing was, when you’re goin’ in to make music that is a whole other thing,” Charlie emphasized.

“The Columbia Studio was union, and the thing about it was in Nashville, in the studios, you had to have the machines to be a certain distance away from the boards so the engineer could not work them both.

“But the thing I remember mostly about Studio A., the big studio, it was the new studio. The old studio, the Quonset hut was the legendary studio where the hits had been cut. Everybody wanted to work in that room. Nobody wanted to work in the big studio until Bob Johnston came to town and basically took it over. Nobody else wanted to be there. He worked with it, got engineers he enjoyed working with like Neil Wilburn, and he actually brought an engineer from New York with him when he first came down.

“With people like Cohen and Dylan…Most of the Nashville sessions, the country artists they would bring a demo in, they’d play the demo, you play it like the demo, you may change a key on it, but basically it’s gonna be the same thing, how they want the demo. So you’re playin’ pretty much inbounds.

“Leonard Cohen and Bob Dylan were singers and songwriters. They write their songs, and they weren’t coming in from a music publishing company. It was a lot different because there is no hurry.”

Elliott Lefko: I promoted all of Leonard’s North American shows during 2008-2013. As a Canadian it was great to see America and learn about the different theatres across the country and get a feel for future tours by like-minded artists.

“One of my favourite writers is Thomas Wolfe. When it came time to choose which cities for Leonard to play, a friend suggested Asheville North Carolina. The theatre there was the Thomas Wolfe Theatre.

“The concert turned out to be my favourite show. The theatre was an old wooden one with great acoustics and the audience was amazing. And the best thing was to get to go to the Thomas Wolfe House that afternoon and see where he lived and worked. Since that day I have sent so many artists to Asheville and it’s always a great show.”

Additional multi-instrumentalists, wordsmiths and producers also gifted me with their vivid memories of Cohen.

Sarah Kramer: It always felt like Leonard knew what he was giving. Like it came from a higher place and wasn’t just in the moment, but for future moments within and beyond his lifetime. As if everything was a conscious gesture but with it, a deep connection or understanding, even within the joys and his wonderful sense of humor. Simple though, light not heavy.

Sarah Kramer: It always felt like Leonard knew what he was giving. Like it came from a higher place and wasn’t just in the moment, but for future moments within and beyond his lifetime. As if everything was a conscious gesture but with it, a deep connection or understanding, even within the joys and his wonderful sense of humor. Simple though, light not heavy.

“I recorded the trumpet part on Leonard’s Dear Heather in his home studio out back. Leanne Ungar was the producer (and engineer). I admired her work on Laurie Anderson’s O Superman as a kid, so it was exciting to get to work with her also. She was so warm and comfortable to work with, as was Leonard, and it was special for me that they dug my sound. I remember her saying it sounded so happy. I don’t think I could’ve been any happier than recording with Leonard Cohen (but I knew what she meant)! He had already worked out a part on his keyboard that he wanted me to play, and I was really tucked in there in the mix, so it’s not like there’s anything super impressive in what I played, but still, I continue to feel honored in having been a part of that.

“I had recorded on another track of his a couple years later called ‘Keep It On The Level,’ with Ed Sanders engineering, but that version was never released. I still have the demo he gave me to work with of just him and his keyboard. Very raw. It’s special to get that little window into his process. It had a New Orleans feel to it when I tracked on it. That song ended up on his latest album, You Want It Darker, as ‘On The Level.’ He totally reworked the song both musically and lyrically. His son Adam produced the album and it sounds beautiful. I especially love the sound of the synagogue choir in the mix of things.

“Leonard once told me that I was his trumpet player… but he never brought trumpet on the road, so again, I think it was more of a gesture, a kindness and generosity he knew he was giving to help me to believe in myself.

“Los Angeles is a tough town in many ways, and he made me feel less alone, even from a distance, as if he was always there. I’m forever grateful for that, for his friendship and kindness. I still feel him here. That’s the thing about living with integrity and treating everyone as if they matter, you give such an enormous gift, and he did that with everyone… those that knew him personally, as well as anyone who listens to his music or reads his writings. I think he was aware of this, and that we’re all in this together.

“His faith, his rituals, from Zen practice to Shabbos, within his writing and in songs, as a person and as a friend, he was always fully present and didn’t seem to waste any time or take anything for granted.”

Daniel Weizmann: It’s Father’s Day and everybody’s wounded: Urban Chaos in the Age of

International Terrorism

“With its sinister, anxious electronic pulse and way-over-the-top

pronunciamentos, ‘First We Take Manhattan’ is Cohen’s most contemporary

song, a wild leap into modern times. Incredibly, he captured the spirit of

our age circa 2014 way back when in 1987! Moreover, in its time, it was

already a definite departure from the dark romance and slow-heartbeat

solemn truths he’s made his name on. The groove almost comes on like a TV

cop show car-chase and, on first listen one can’t help but wonder if one

is being put-on. This is Cohen?

“Then came the narrator, just as unreliable, an ideologically twisted despot

or terrorist or just-plain kook, fueled by a bizarre combination of

entitlement, rage, and spiritual purpose. ‘I’m guided by the beauty of our

weapons,’ he sings, with that ‘straight-face’ gravity that only Cohen can

pull off. Whoever he is, he’s a nut. And yet, at times, the narrator also does

sound like the Cohen we know, the weary poet of post-Holocaust

consciousness, struggling to find his sea legs in the Information Age soul

tsunami. ‘You see that line there moving through the station? I told you, I

was one of those.’

“Finally, the song refuses to rest on a position, but, like the modern

world, rants with conviction at us from all ends, keeps us in a state of

suspension, via enervating switch-ups and clashing imagery — everything

from the fashion biz to the plywood violin to the groceries. ‘Remember

me?’ the narrator confides, ‘I used to live for music.’ And he says that in

a song, an astonishing real-time self-disavowal!

“Even more than Cohen’s other gems, this track, originally recorded by

Jennifer Warnes, has proven to be a great lyrical Rorshach test. The

internet has plenty of interpretations that range from the bizarre to the

brilliant. One talk backer described the song as ‘globalization from the

point of view of someone from the underdeveloped part of the world.’ Others

grasp at similar but disparate puzzle pieces: it’s about mega-corporations,

about hyper-capitalism, about foreign policy, expansionism, terrorism,

about the blurring and unraveling of national identities, it’s about the

West German Red Army, it’s about radical chic.

“Cohen himself tried to explain the song to Paul Zollo in the April 1993 issue of Song

Talk. ‘I felt for some time that the motivating energy, or the captivating

energy, or the engrossing energy available to us today is the energy coming

from the extremes. That’s why we have Malcolm X. And somehow it’s only

these extremist positions that can compel our attention. And I find in my

own mind that I have to resist these extremist positions when I find myself

drifting into a mystical fascism in regards to myself. So this song, ‘First

We Take Manhattan’, what is it? Is he serious? And who is we? And what is

this constituency that he’s addressing? Well, it’s that constituency that

shares this sense of titillation with extremist positions. I’d rather do

that with an appetite for extremism than blow up a bus full of

schoolchildren.’

“Decades later, with the world’s appetite for extremism at a fever pitch,

and the Twin Towers of Manhattan long-ago razed to the ground, ‘First We

Take Manhattan’ is an almost frightening act of clairvoyance.”

Chris Darrow: I hadn’t seen Leonard Cohen since the 1967 Songs of Leonard Cohen recording sessions 35 years earlier. In 2002 he had been cloistered at the Mt. Baldy Zen Center in Southern California, near my hometown of Claremont, so I knew he was hanging around my area.

“One day my father, Paul Darrow, was having an art opening in downtown Claremont, and I heard that Cohen was spotted sitting outside at a local Greek restaurant called Yiannis. I strolled over to where he and his female companion were drinking coffee and smoking at an outdoor table. His head was shaved and he was wearing a robe of a Buddhist monk.

“I said, ‘Remember me?’ He graciously replied, ‘Of course I do, you guys saved my album.’ And he went on to explain that our appearance at that time had allowed him to realize his vision and get the sound he was searching for.”

Cohen then continued his audio expedition. Newcomers to his catalog might want to check out The Essential Leonard Cohen.

The very last visual I have of Leonard Cohen in 2014, looking like a cross between Dustin Hoffman and John Cassavetes, was sticking his right hand across a table at Canter’s Delicatessen in Hollywood and offering a long and firm grip.

I turned to Sirius XM deejay Rodney Bingenheimer who mused, “We recorded on one of his albums…”

I then devoured a plate of dill pickles as Leonard cashed out at the register.

I am grateful for two websites that have provided sanctioned and official information on the life, influence, activities and products involving Leonard Cohen.

Jarkko Arjatsalo in Finland oversees

www.leonardcohenfiles.com and www.leonardcohenforum.com.

Blogger and Cohen advocate Allan Showalter in America helms

www.leonardcohen.com/link/cohencentric-leonard-cohen-considered

You can also visit www.leonardcohen.com

Leonard Cohen photos and album covers courtesy of the Sony Music Archives

Kaleidoscope/ Nico 1967 Scene advertisement courtesy of Chris Darrow

Harvey Kubernik is the author of 12 books, including Leonard Cohen, Everybody Knows, and Neil Young, Heart of Gold. In April 2017, Sterling published Kubernik’s 1967 A Complete Rock Music History of the Summer of Love.

Harvey Kubernik’s literary music anthology Inside Cave Hollywood: The Harvey Kubernik Music InnerViews and InterViews Collection, Vol. 1 will be in November 2017, by Cave Hollywood. There is a Cohen tribute chapter.

Kubernik is also writing and assembling a multi-voice narrative book on the Doors.

Over his 44 year music and pop culture journalism endeavors, Kubernik has been published domestically and internationally in The Hollywood Press, The Los Angeles Free Press, Melody Maker, Crawdaddy!, Variety, The Hollywood Reporter, MOJO, Shindig!, HITS, The Los Angeles Times, Ugly Things, Record Collector News magazine, and www.rocksbackpages.com, among others.

Kubernik is a record producer, a radio, film, television and Internet interview subject and a former West Coast Director of A&R for MCA Records. Harvey has penned the liner notes to the CD releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, The Elvis Presley ’68 Comeback Special and The Ramones’ End of the Century. Kubernik serves as Contributing Editor of Record Collector News magazine and displays articles and essays on www.cavehollywood.com on a monthly basis.

In November 2006, Kubernik was invited to address audiotape preservation and archiving at special hearings called by The Library of Congress and held in Hollywood, California).

During July, 2017, Harvey Kubernik was a guest speaker at The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame’s Library & Archives Author Series in Cleveland, Ohio discussing his 2017 book 1967 A Complete Rock Music History of the Summer of Love.