By Harvey Kubernik c 2018

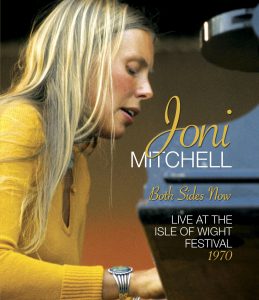

On September 14, 2018, Eagle Vision released Joni Mitchell Both Sides Now: Live At The Isle of Wight Festival 1970.

In 1970, the Isle of Wight Festival was one of the largest musical events of its time. Bigger than Woodstock and controversial from the get-go, hundreds of thousands of people descended on the island. Many of those without tickets set up camp on a hill overlooking the festival site, opposing the consumerism of the event and intent on “taking the music back” by any means necessary. It was a celebration of hippy counter culture gone awry, and in Joni’s words “they fed me to the beast.”

Singer/songwriter female troubadour Joni Mitchell took to the stage to deliver an outstanding performance against all odds. At times, it was a battle against the audience, as they tore down barriers and shouted obscenities. Her set was interrupted multiple times, including one man invading the stage trying to address the crowd.

She later commented, “It seemed like an appropriate time to flee…”, but still the seemingly fragile folk-rock singer stood her ground. Instead she returned to her piano, sitting on a fold-up wooden chair, and made an impassioned plea for respect from the audience, continuing her set with “My Old Man,” she won over the crowd and the atmosphere softened. In response the front page of Melody Maker hailed her with the front page headline, “Joni triumphs!”

In viewing Joni Mitchell Both Sides Now: Live At The Isle of Wight Festival 1970 we are reminded how on August 29, 1970 she defiantly challenged the unruly throng and somehow completed her bold solo set

Directed by Academy Award winning filmmaker Murray Lerner, who sadly passed away shortly after the film’s completion, Both Sides Now: Live At The Isle of Wight Festival 1970 incorporates new interviews with Joni, discussing her recollections of the event intercut with festival footage, both onstage and behind the scenes, offering a fascinating insight into a now legendary concert from the artists point of view and putting the events of the day into context.

Alternatively, fans can enjoy the uninterrupted live concert footage featuring classic songs such as “Woodstock,” “Both Sides Now,” and “Big Yellow Taxi.”

Track listing:

1) That Song About The Midway

2) Chelsea Morning

3) For Free

4) Woodstock

5) My Old Man

6) California

7) Big Yellow Taxi

8) Both Sides Now

9) Gallery

10) Hunter

11) A Case Of You

On November 6th and 7th, in honor of Joni Mitchell’s 75th birthday, a slew of recording artists are booked at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion venue in downtown Los Angeles who will perform some of her songs in a fundraising gala for The Music Center complex: Graham Nash, Chaka Khan, Kris Kristofferson, Emmylou Harris, Los Lobos, Seal, Rufus Wainwright, Norah Jones, Diana Krall, and Glen Hansard. Brian Blade and Jon Cowherd are serving as musical directors.

No doubt several Mitchell compositions heard and seen in Joni Mitchell Both Sides Now: Live At The Isle of Wight Festival 1970 will be in that 2018 stage repertoire.

Mitchell has not been confirmed to be present at the tribute. She has been going out in public in 2017 and 2018 since she suffered an aneurysm in 2015.

I had a very brief conversation with Joni Mitchell in West Hollywood at Book Soup on Sunset Blvd. just days before her life-threatening injury.

I was signing a few of my Canyon of Dreams: The Magic and the Music of Laurel Canyon 2012 paperback editions one night at the store, and afterwards watched Toni Stern’s poetry reading with photographer Nurit Wilde and librarian Gary Strobl from the Henry Diltz studio. Lyricist Stern is a co-writer with Carole King on Tapestry. They penned “It’s Too Late,” and “As We Go Along,” for the Monkees’ Head soundtrack.

Joni walked into Book Soup and waived to Nurit. They’ve known each from the mid-sixties from Canada. Nurit introduced me to Joni.

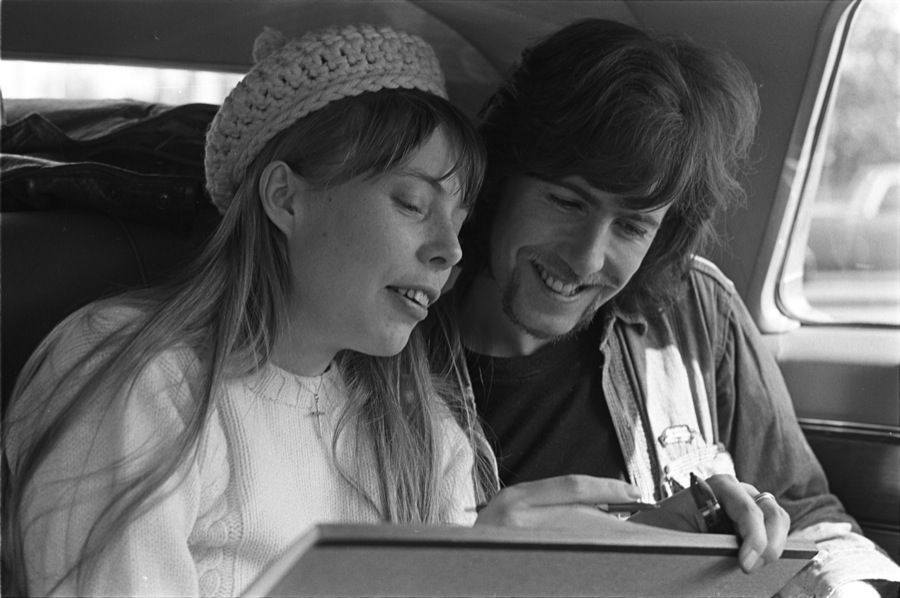

I had actually met Joni on several occasions going back to 1970, at Art’s Delicatessen in Studio City and Greenblatt’s Delicatessen on Sunset Blvd., when she and Graham Nash were living together 1969-1971 in Laurel Canyon. Another time I was in a booth next to them at the Musso & Frank Grill. Graham loved their Flannel Cakes. He last ordered them in 2008.

Nurit and Joni are two of the cover photos that grace Canyon of Dreams. Joni comically remarked, “You can never go wrong having two blondes from Canada on the front of your book!”

Mitchell was further delighted I had just finished a book on Leonard Cohen. “You must have a thing for Canadians.”

Joni also mentioned she was doing some work with a record label [Warner Music Group] assembling a box set but still determining the track selections and sequencing. She reminded me of the work guitarist Robben Ford did with her in The L.A. Express.

In September of 2018 I was sent an advance link of Joni Mitchell Both Sides Now: Live At The Isle of Wight Festival 1970. I simultaneously heard that Graham Nash would be returning to Los Angeles for his intimate evening of songs and stories on October 11th at The Theatre At Ace Hotel. I immediately emailed Graham, requesting “I Used to Be a King,” from Songs For Beginners, written in 1971 about his breakup with Joan. His same day response was “It shall be.”

Born in Philadelphia Pennsylvania on May 8, 1927, raised in New York City, and a graduate of Harvard University in 1948 with an English and poetry major, Murray Lerner’s award-winning and trend-setting musical documentaries include long-form 1970 Isle of Wight studies of The Moody Blues, Leonard Cohen, Miles Davis, The Who, Jimi Hendrix, Jethro Tull, and more recently The Doors and the long-awaited Joni Mitchell portrait, now thankfully entering the retail universe.

In 2008 Lerner produced and directed The Other Side Of The Mirror Bob Dylan Live At The Newport Folk Festival 1963-1965 DVD released by Columbia Records and Legacy Recordings

Over the years I interviewed Murray Lerner a few times. My brother Kenneth and I hosted a question and answer session with Lerner one evening in Hollywood at the American Cinematheque Egyptian Theater in August 2010 as part of Martin Lewis’ Mods and Rockers film series.

I cited Murray’s landmark movie Festival! in my 2017 book, 1967 A Complete Rock Music History of the Summer of Love. Lerner’s voice is also quoted in my books on Leonard Cohen, Everybody Knows (2014) and Hollywood Shack Job: Rock Music In Film and on Your Screen(2004).

In September 2017, Criterion announced a director-approved special edition of Festival! It’s a new reconstruction and remastering of the monaural soundtrack utilizing the original concert and field recordings and presented uncompressed on the Blu-ray DVD.

Lerner died of kidney failure on September 2, 2017 in Long Island, New York at age 90.

In 1995 Lerner released Message to Love: The Isle of Wight Festival 1970. It’s a fascinating document of the troubled 1970 Isle of Wight Festival attended by some 600,000 people, the vast majority of whom refused to pay for their admission.

The gathering was an event organized by promoters Ray and Ron Foulk, via their company Fiery Creations Ltd. along with another brother, Bill Foulk. Rikki Farr served as compere.

Lerner’s Isle of Wight films are a sophisticated analysis of the darker side of the period’s much hyped festival. They juxtapose the struggles of the promoters with impressive performances by The Who, Jimi Hendrix, Free, Emerson, Lake and Palmer, Lighthouse, Joan Baez, Ten Years After, The Moody Blues, John Sebastian, Joni Mitchell, The Doors, Jethro Tull, Taste, and other acts.

During my 2009 and 2013 interviews with Murray Lerner, we talked about the Isle of Wight.

Q: What is it like returning to The Isle of Wight scenario of 1970?

A: 20 years ago I revisited the footage when the DVD world really started happening. I re-lived it and it was very exciting

Q: What about Joni Mitchell from Isle of Wight?

A: I’m very excited about the possibility of the Joni Mitchell one. The whole set. I’ve been dealing with Elliott (Roberts). There are a few more Isle of Wight things I’d like to do. Like the Doors. [In February 2018, The Doors: Live At The Isle Of Wight 1970 was released on DVD + CD, Blu-Ray + CD]

Q: How did your Isle of Wight film and resulting DVD’s of performers from this event initially happen?

A: From the Newport festivals on I decided I wanted to show something behind the scenes in the music business. Not just the festival, because I saw the festivals were not quite as loving and peaceful as it seemed. Every night there would be big meetings at Newport until two or three in the morning arguing about who was gonna be next and the order of the lineup, all of that. And you never saw that and I was startled… How many blacks? How many Appalachian singers? So I decided I would like to turn the cameras the other way at some point. And then when I saw Woodstock, I decided I had to because I thought it was phony, so that made me determined to do it.

And then by chance, really, when (Bob) Dylan was breaking up with (Albert) Grossman, and Bert Block, who became an agent for (Kris) Kristofferson, at the Isle of Wight festival, he came to me. He had been Grossman’s partner and now was with Jerry Perenchio’s Chartwell Artists. He liked my movie Festival! He said these the promoters from England came to America and asked him to get the performers for the 1970 Isle of Wight. They wanted to run and screen Festival! So I said fine, “But I’d really like to make a film.” OK. That started me down this path. And they did make a deal with me to license Festival! They even rented two projectors. You can see them in a sequence with Tiny Tim.

I decided to do a film. So then we started to negotiate and talk. Everyone wanted to do this film. And I organized an English crew of about nine. And I had one person from staff, a guy who had been my assistant on a lot of shoots.

I tend to make documentary films after thinking about it and researching it and having a concept in mind and finding iconic images that resonate with that concept. That’s the way I work. I had done a number of industrial films with sophisticated photography and editing before I did Festival!

I had a loose outline between the idealism of the music and the commercialism of the music business. I predicted what would happen. Conceptually, I thought the counter-culture, having followed it, was being co-opted commercially, kids were getting angry and I knew there would be tremendous tension and anger. I knew it was brewing, and one of the people interested in it was in England.

Q: Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell and other Isle of Wight subjects are captured in color. The earlier Newport Festival 1963-1965 artists were shot in black and white.

A: I shot color for the Isle of Wight performers. It was high-speed Ectochrome reversal. And I’m glad I did it because the color lasts a lot better in reversal. The camera people I had were with their own cameras for the most part but they used Arriflexes, and Auricon reflexed and a new camera, the main camera man used an Aaton, a kind of avant garde camera at the time.

Q: What do we get in black and white that we don’t get in color?

A: Well, you get an absence of distracting noise I would call it. Because you’re locked in to just the scene itself. And not the palette in which the palette changes from shot to shot quite often which it doesn’t in black and white.

Secondly, I think black and white removes a certain level of communication that is often unnecessary. And so what are you getting in color is more reality, more vividness but I’m not one who believes that film is real.

I always use very long lenses as an adjunct to my photography. I believe in the long shot because I would like the thing to feel musical and not jumpy. I think film is visual music. And it should be, and I believe in editing that way. You can have moments where you are doing quick montage, most of the time you need to relax.

I like really long shots and before anyone ever did it, I used 2,000 millimeter lenses and for crowd shots, moving in slow motion. A lot of unusual stuff. I love people coming towards the camera and coming into close up. And then I got a 600 millimeter lens for my 16 millimeter camera, played around with it during Sonny Terry and Brownie McGee at Newport. Real close ups.

Q: What was the one thing you learned from your Newport Films that was applied to the Isle of Wight job?

A: First of all, on the technical side, I learned and made sure everyone examine and perfect their equipment so that they were sharp to be on a very literal level. Sharp when they were close in and wide angle. Very often when you go to a wide angle it can lose focus. So I had them check their cameras for that problem and fix it. And, going from there, I had to call them all together and explain what I don’t like. I don’t like, and some of them did it anyway, I don’t like fast pans, fast zooms.

I said, “If you are panning over to a musician that is playing but you don’t see because he comes in after the musician is on go slow. You’ll hear the person and it will be more dramatic than if you swish the camera or zoom in.” That is one of the big things.

And, I don’t mind looking into the lights for effect. A bunch of stuff I directed them to do. I took special shots, positions. I personally have a technique where I practice the choreography of the camera. Every day for about an hour before I shot, having an assistant stand by and I would focus, zoom and figure out how big the moves had to be to get the result I wanted so I could do it myself. And I practiced all of that. And I kind of instilled that sense that of the choreography of the camera being part of the concert.

For the most part, in the planning stages, I picked positions to shoot. And I told people, “You concentrate on the close up and you concentrate on something else.”

I remained calm during the filming. That’s the way I am. I’m anxious inside but I’m calm. That’s why I don’t like frenetic movements of camera and all of that. I was too intensely involved making the movie to concentrate or think about any correlations between the artists on stage or aspects that blended the musical with the spiritual. There was a separation in time from one to another over a few days. I didn’t have any interaction with any of the performers. I was working! I couldn’t get backstage to do that. One thing after another, but I had access for some dead on shots.

Q: Reflect on the Isle of Wight?

A: The 1970 Isle of Wight journey was worth it. That was the most exciting event I’ve ever been to. ‘Cause it was so all encompassing and new. In terms of the possibility of the crowd killing us and always living on the edge of that precipice, and all the different personas that reacted to this thing. Rikki Faar was interesting.

And I was always thinking, in relationship to the performers, “What’s my role in what they are singing about? How do I fit into that?” I change with each one as I am watching them. Like with The Moody Blues, I did a DVD with them from the Isle of Wight. They were different. Jethro Tull was different. I liked the music of The Moody Blues. It was different and interesting, and like Leonard Cohen, it had an undercurrent of mysticism to it.

Q: Your Isle of Wight footage from 1970 was done before cable television, the home video market, and later the existing DVD format. I know it took you many business meetings to convince movie studios and also record labels to collaborate with you on acquisition, licensing and creating physical hard product from this monumental event. Message to Love, a compilation, was finally out in 1995.

A: I made a great 70 minute demo reel, not a weak one. Howard Alk helped me initially edit a little demo reel, and a lot of heavyweights liked it. But then Howard moved to the west coast to live on Dylan’s property editing Renaldo & Clara.

I was a bad salesman. It was very exciting. At the time no one wanted to put money into it. And, at the time, it was unfunded but I was interested in theatrical not DVD.

Also, at the time, and this was as the DVD market was first really developing, some people at companies liked the music and some people liked the behind the scenes. But the combination of the two they didn’t get. More often, the attack on money was something the music business wasn’t that interested in showing. And there was a little bit of that.

It was really exciting. Everyone loved it but wouldn’t back it. They didn’t think the music would sell. They didn’t think the political aspect would sell. But I knew The Who, Jethro Tull, Leonard Cohen. Miles Davis, Joni Mitchell and The Doors were potent performers on stage and on camera. Absolutely. And, there was a feeling “Oh well, these are older acts,” which I never agreed.

Q: You have witnessed the rock and music documentary develop over 50 years, along with D.A. Pennebaker, Ricky Leacock, and Albert and David Maysles. And forged alternative theatrical venues, creating the environment for budding independent filmmakers who have benefitted from the group’s pioneering music documentary product exhibition the last half century.

Have you done panel discussions with them in front of film students? At most of these conferences today they want to know about hustling an agent and the royalty points on the back end of a movie deal, and not even concerned about film stock, lenses or tips to capturing the story.

A: The best one of those was at the Santa Fe Film Festival, a documentary panel. Pennebaker was there. (Ricky) Leacock was there. I was there. It was a seminar type thing where people would question us afterwards.

It was all about how do you get the money? Not about creative stuff but financial. One kid said to Pennebaker, “How do you get the money to finance a film?” And without missing a beat he said, “Marry a rich woman.”

(Harvey Kubernik is the author of 14 books. His debut literary music anthology Inside Cave Hollywood: The Harvey Kubernik Music InnerViews and InterViews Collection, Vol. 1 was published in December 2017, by Cave Hollywood. Kubernik’s The Doors Summer’s Gone was published by Other World Cottage Industries in February 2018. In November 2018, Sterling/Barnes and Noble will publish Kubernik’s The Band From Big Pink to the Last Waltz.).