Harvey Kubernik interviews filmmaker Jonathan Holiff on his documentary My Father and the Man In Black.

Harvey Kubernik interviews author Robert Hilburn on his definitive biography JOHNNY CASH: THE LIFE;

Inducted into both the Country Music Hall of Fame and Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, winner of a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, and a Kennedy Center Honor, Johnny Cash on September 12, 2003 left the physical planet at the age of 71. His status in the last decade has only grown as a musical, spiritual, literary and retail influence. Cash and I have the same February 26th birthday.

The 2005 biopic on his life Walk The Line grossed more than $300 million and his posthumous albums have totaled over $130 million.

In 2006 his final studio album, American V: A Hundred Highways, went to #1 on both the Pop and Country charts.

In the summer of 2013 the U.S. Post Office selected Johnny Cash as one of the three musicians chosen to inaugurate the new Music Icons stamp series.

“It just truly embodies my father’s spirit, who he was,” his son John Carter Cash said. “It’s different. That’s one thing: It stands out to me as being unique. It’s very commanding when you see the stamp.”

The stamp is based around a promotional shot for the 1963 album Ring of Fire: The Best of Johnny Cash. To John Carter Cash it looks like a 45 or 78 RPM record cover and is unlike the usual offerings – matching his father’s legacy.

“He had sort of a magic and a charisma about him,” the younger Cash suggests. “If he walked into the room and your back was turned, you felt the change. He had that strength about him. That legacy that he began still lives on in many ways. It’s still alive in the hearts of fans.”

In 1975 I conducted an interview with Cash in Anaheim, California for Melody Maker and Johnny commented about choosing songs to record and perform in his live concert repertoire.

“In concert I sing ‘Sunday Morning Coming Down,’ the Kris Kristofferson tune, that’s so much of me that sometimes I feel like I wrote it. There are some songs that I must write for self-expression. If a song comes along I must acknowledge it. I’ve recently recorded a song ‘Strawberry Shortcake.’ It’s about a guy who went into the Plaza hotel in New York and stole a cake. It’s a novelty song. But there are some songs that I had to write like ‘I Walk The Line’.”

The Columbia/Legacy label has released a slew of stellar Cash CD reissues and box sets this century. Many Greatest Hits and Best Of packages are constantly available.

In 2012 the company pressed up Johnny Cash-The Complete Columbia Collection. Containing 61 distinct album packages (single and double CDs, totaling 63 discs overall) housed in a box with a lift-off cover. The deluxe product also follows up the critical and commercial success of The Johnny Cash Bootleg Series, which has presented four historic releases to date. Released in April, the most recent title in the series is The Soul Of Truth: Bootleg Vol, IV, which includes 51 gospel-themed recordings.

In addition, a couple years ago, Johnny Cash-The Great Lost Performance was stocked by Island/UME Records. It’s the first-ever CD release of a classic 1990 live show, remixed from the original multi-track tapes, with several songs Johnny rarely performed live. Cash and his revue were captured on stage at the Paramount Theatre in Asbury Park, New Jersey on July 27, 1990. The album contains the only concert version of “Life’s Railway To Heaven,” whose studio version by Cash was released posthumously.

Also worth investigating is The Johnny Cash Project, a global collective art project now displayed at the websitehttp://www.thejohnnycashproject.com/.

Participants from all over the world were incorporated into this endeavor initially developed around a music video for “Ain’t No Grave” that were strung together and integrated in sequence over the song. New people are encouraged to contribute so this living portrait evolves and is never the same video. The Johnny Cash Project is a collaboration between the Cash Estate, record producer Rick Rubin, Radical Media and digital media artist Aaron Koblin, who leads the Data Arts Team at Google.

In October 2013 the documentary, My Father and the Man in Black, a film by Jonathan Holiff was distributed on DVD by Passion River Studio after a critically acclaimed film festival and theatrical run.

“Heart and feeling is soaked through it like the sweat in Cash’s guitar strap,” Alan Scherstuhl offered in The Village Voice. “A fresh angle on the Cash mythology–a long way from Walk The Line,” described Steve Rose of The Guardian. The New York Times hailed the flick as “complex and haunting,” Variety lauded it as a “uniquely intertwined dual portrait,” while The Wall Street Journal reported, “You thought you knew Johnny Cash. Think again!”

THE TRAILER can be viewed at http://youtu.be/jtovAxxPo2Q

The movie is available on iTUNES and Amazon. www.Johnny-And-Saul.com

In the U.K. and Ireland the film is available via Ballpark Film Distributors. My Father and the Man in Black has been sold to British, Swedish and Australian television, after playing on Canadian TV.

Holiff was a talent agent at William Morris for a couple of years, later operating a celebrity endorsement agency for fifteen years. He would pair clients Martin Scorsese, Dennis Hopper, Britney Spears, Faye Dunaway and Don Johnson with Fortune 500 Companies like General Motors and Sony Electronics. He is a former television producer for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and responsible for the first Canadian TV appearances of Celine Dion and Alanis Morisette.

Long before there was Johnny and June, there was Johnny and Saul, from 1960 to 1973.

My Father and the Man in Black is a movie that features one of the 20th-century music’s known icons while also telling the inside story of Johnny Cash, his talented but troubled manager, Canadian impresario, Saul Holiff, and a son Jonathan, named after Johnny Cash, seeking his father in the shadow of a legend.

Following his dad’s 2005 suicide, filmmaker Holiff discovers hundreds of letters and audio diaries, including recorded telephone calls with Johnny Cash during his pill-fueled 1960s, triumphs at Folsom and San Quentin, marriage to June Carter, and his conversion in the early 1970s to born-again Christian.

Director, writer and producer Holiff, over seven and a half years, has assembled these items for a revealing behind-the-scenes view of the complex relationship between Cash and his long-suffering manager, both struggling with personal demons. The utilization of never-before-seen footage, artifacts, believable re-enactments and voice-over narration serve as a catharsis for its maker.

Harvey Kubernik interviews Jonathan Holiff

Q: What was the genesis of your movie?

A: My father killed himself. I hadn’t spoken to him in twenty years and this was a journey of discovery. The film was done without askinganyone’s permission. If you want to  see a hagiography read the other books and watch the other documentaries. But if want to see it stripped down, with no corporate interference, from the inside point of view, I think that’s what we have with this story.

see a hagiography read the other books and watch the other documentaries. But if want to see it stripped down, with no corporate interference, from the inside point of view, I think that’s what we have with this story.

Q: Why did you do the film?

A: Well, it was really a mental health exercise. Since I was a teenager I spent many years trying to better my father professionally. If he wasn’t gonna love me or respect me, then I’m going out into the world and be bigger than Saul Holiff ever was in show business. So I was on this mission to get his approval and he kills himself. No one left to prove anything to I fold up my business in L.A. and drive home to Canada. And three months later this movie, Walk The Line opened. Our phone starts to ring and it won’t stop.

“The Toronto Globe and Mail in Canada published a full page obituary on Saul and these papers only do full pages for people of importance. I had no idea. People across Canada were contacting my mother, figuring she hadn’t seen it. I learned a lot about my father from his obituary.

“Then fans started to call about memorabilia and if it ‘needed a good home.’ Several Cash biographers phoned. All wanted to know about the Johnny and Saul relationship. ‘Why did Saul quit when Johnny was on top?’ Managers don’t quit superstars they admonished. Then there was the media in Canada who wanted to know what I thought about Walk The Line, which I had not seen. I read the trades for a living and when I saw Reece Witherspoon was attached, I knew they were telling a love story. So I didn’t expect to see Saul portrayed in the movie. It was a conspiracy of events that forced me to finally yield where I would go see the movie in a theater or on DVD.

“I thought the movie was terrific. I thought Joaquin Phoenix was robbed (of an Oscar). These Hollywood glossy movies are served up to us. And even though we see the disclaimer based on a true story, even we filmmakers tend to forget they take liberties with the story.

“For example, in the first act of that movie they showed Johnny, June and Jerry Lee Lewis in a black Chevy driving from gig to gig in the South in the mid-1950s. And Johnny and June were never in the same city on the same stage professionally until my father hired June in December 1961. As writers we call it invented backstory. I enjoyed the movie.

“At that point I realized I was born the year Johnny was arrested in El Paso. And I started wondering if I had given my father a hard time and maybe he had his hands full when I came into the world. Suddenly watching Walk The Line, I was unable to follow it as it opened a floodgate of heretofore repressed memories of childhood. Suddenly it all came back to me. And that night I went into his storage locker. But it was never to make a movie.

Q: Opening Saul’s storage locker was locating the lost city of Atlantis.

A: People often call it a secret storage locker. It wasn’t secret but it was unknown to me. And the reason I went there that night after viewing Walk The Line was because my mother had told me. I tried going twice before but was unable to cross the threshold. I didn’t want to wade into my father’s life. I’d been practicing denial about our relationship for years. I was trying to escape Saul Holiff by leaving Hollywood and run smack right into him in Canada with Walk The Line opening.

“I’m at the locker because my mother said it was his locker, not hers. It was where he kept everything that was important in his life. He was obviously a bit of a narcissist. All good managers are incredibly well organized. They are list makers. They keep important documents for years. The fact is, I wanted to know if there was a picture of me or my brother or anything about his children in this locker. That’s why I went there. And to discover all this Johnny Cash stuff was mind-blowing.

“But again, I wasn’t there for Johnny Cash. I was there to learn more about my father who I did not really know. This started out basically as a journal. I’ve said it was an effort at some kind of therapy. And my mother read pages of the journal one day and she said I should write a book. I told her I wasn’t a writer but had worked in television in Canada for many years and felt it might make a one hour documentary about manager and star. But having lived in Hollywood for many years I sent my first treatment to friends like David Shore, who created (the TV series) House and these guys wrote back to me and said this is a movie and should be told from your point of view.

Q: Your dad had been a concert promoter in Canada in the fifties, bringing Bill Haley and the Comets to the country. Before embarking on a management trek with Johnny Cash for almost a decade and a half, and then voluntarily quitting. He put up with a lot of crap regarding Johnny, who sometimes didn’t appear for shows.

A: My father has been asked about Johnny and also their split. He has been quoted in publications, “I was no victim here. I went into this with my eyes wide open.” He was philosophical about it. It was a crazy time. One promoter in Ottawa mentioned they had to practically prop Johnny up at the microphone to keep him up.

Q: But your father and Saul did maintain a friendship or correspondence for many years after their professional split.

A: There was a visit to Jamaica to the Cash home. These men kept corresponding for years afterwards. If there was acrimony and someone fired, that would have never happened obviously. But it’s all on the record. Saul understood the big picture of working for the artist. Back in the day, this was before there were agents, the advent of the California Charter, you know, making agents responsible for getting people work and managers for directing people’s careers and not getting people work. My father was part of the old guard that was known as personal managers. And he basically took his job as directing Johnny’s career from a macro oversight kind of way.

Q: What I found refreshing about your movie was a real glimpse into the early career of Johnny Cash that rarely gets examined at length in most books and documentaries.

A: Bottom line, let’s face it. There is, for whatever reasons, this kind of revisionist history that goes on. I get it. If I was a manager who followed Saul, or (Brian) Epstein or Col. Parker, whatever the case may be, I would certainly write myself into the story and write the other guy out. Especially if he’s dead or living in a far-way land known as Canada.

“The fact is I never invited the Cash family, Cash estate or Sony Music to approve this project. That would invite influence on the story line. And I couldn’t legitimately live with myself and call it a documentary if I had to do it by someone else’s leads.

“But then again, I’m also a polite Canadian. So the first thing I did was drive to L.A. in 2007 and I presented myself in person to Lou Robin, (Cash’s manager since the mid-seventies) and I told him I was making this. And I wanted to inform him in advance and then when I had rough cuts I sent to all the kids in the family. So I’ve always been upfront about disclosing what I was doing. I hired the best lawyer in Beverly Hills, Michael C. Donaldson. He represents Haskell Wexler, Werner Herzog, and Kirby Dick. For the last twenty five years he’s been an activist attorney on behalf of documentary filmmakers and an expert in fair use. And consequently I moved ahead with the project without anybody’s permission. It was all diligently managed and directed by attorneys what we could and could not do.

Q: The wealth of materials, images, photos, mug shots, arrest records, concert posters is staggering. And, owing to fair usage legal laws, you were able to have taped telephone calls between your father and Johnny incorporated on screen. I’m sure it changed the dynamic of your movie. We really hear them speaking to each other and that personalized it.

A: Yes. They were recorded before laws were enacted in the U.S. and Canada, and both men were dead. This is brand new stuff, too. Johnny was the greatest at mythologizing of everybody we’ve ever heard. This is a stripped down behind-the-scenes look at the real deal. Even the hardcore Cash fans love the movie because it is a whole new side to Cash we never get to see. As a first time filmmaker I really enjoyed tackling the subject of modern myth-making

“It’s a passion project. It’s the one thing I’ve ever done in my life that was absolutely pure and without agenda. It was an obsession. I could not have made this or raised the money privately and shot this movie on film if I hadn’t been absolutely obsessed with getting to the bottom of who the fuck my father was.

Q: What have your Q. and A. sessions like around the world after the movie was screened?

A: When we first screened it I was gratified by the positive reviews. Then when we went on the film festival circuit the questions I had lived in fear of was that everybody would only ask about Johnny Cash. “What was it like to know Johnny Cash?” “How did he treat you as a kid?” And the reality of the matter is that 85 per cent of the questions in an audience Q. and A. are of a personal nature. Or they want to relate from experiences with their own families. A father son or mother daughter dynamic.

“The fact is, it has much broader appeal than a Johnny Cash or even a music documentary. The word of mouth and people recommending the movie to friends, who didn’t know the music of Johnny Cash, and found the father and son story. We found that it just seemed to expand that way. And it’s also a cautionary tale about the music industry.

Q: I imagine there are questions about the reasons behind the tape recordings between your father and Cash.

A: One of the questions I am asked at these Q. and A. sessions is, “Why did your father make these recordings. Was he trying to get the goods on Johnny Cash?”

“And the fact of the matter is I know exactly why he made these recordings. Of course there are two answers. Where the audio diaries are concerned, my father was the archetypical fifties male and the idea in those days of seeing a shrink was absolutely taboo. And my father was dumping his feelings, emotions and angst into tape recorders as a means of conducting his own therapy.

“But when it comes to the phone calls I’m unabashed when I say this, my father has said, and Johnny has famously said, ‘that there are two of me. Johnny is the good guy and Cash causes all the trouble.’

“In the mid-1960s Johnny was taking so many pills, that, according to Saul, he literally developed a split personality. There was the good Johnny and the bad Johnny. So Saul would be in an office with Johnny, ‘what do you think about playing Miami the third week of January, tying it into the third week of a tour?’ And Cash would say, ‘let’s do it.’ And the next day, Saul would put the contract in front of him and he’d say, ‘I didn’t agree to this. I didn’t say I would do this.’ And Saul said, ‘What are you talking about? You just said yesterday you would do this.’

“So Saul started a practice in the 1960s of having June witness all of their important conversations. Saul was constantly getting June to back him up on these dealings. So when the technology came along that afforded him the opportunity to record, it was simply that. If my father wanted to write a tell-all book, he had 35 years to do it and it just wasn’t his style.

“Among the better compliments I get from reviewers is when they talk about this movie being a dignified portrait. Showing some restraint and not tabloid in nature. It’s not sensationalistic and not meant to drag Johnny Cash through the mud. Both Johnny and Saul, by all accounts, are treated equally and without prejudice. But what I can tell you is that I show a lot of restraint. Because I found a lot more shit in that locker that’s in the movie.

Q: You are an admirer of Johnny Cash and his music.

A: I also love Johnny Cash. I’m a huge fan. I saw him at Madison Square Garden. And there is no denying he was an original. It was Saul who basically said to Cash “you are no longer a country and western performer. Those two words are verboten. You’re now unique, alone and here are some slogans I want you to look at.” My father was the first one who basically told him, “We are not going to categorize you or let you be categorized.”

“There are people out there who don’t understand that there are a lot of nuts and bolts people like my father and others who are around such a person and help them get to where they are going.

“And I got to see Johnny to have, and for all intensive purposes, the biggest comeback in music industry history, courtesy of Rick Rubin, which was a very joyful thing. I loved the Hurt video.

Q: You selected specific music for the soundtrack. The movie ends with Cowboy Junkies’ “Staring Man.”

A: For me it became my fathers’ version of “Hurt.” The lyrics speak to my father being the observer and spotting all the cracks in the faults but being unable to do anything about it.

“The music selected was done very carefully. Obviously, everything that had to be licensed, things not fair use, were licensed along traditional channels. And let’s remember, there’s Dave Brubeck in this, there’s the Andrews Sisters, Bill Haley and the Comets, all had to be paid for and licensed.

“I chose Haley because Saul was the first to bring rock and roll into Canada. The dirt on my father in the country music business was the joke on Saul was he did like country music. He didn’t listen to it. The only thing he listened to was classical and jazz. And I grew up hearing my father blast Brubeck every single day in my childhood. I was just a kid when my father retired at the age of 49 and went back to university. I think he’d get a real kick out of this film.

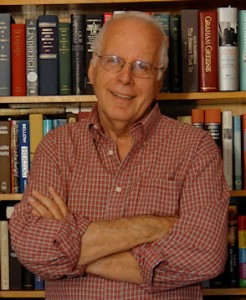

And coming in late October is a definitive biography of the Man in Black, JOHNNY CASH: THE LIFE. Published by Little, Brown and Company, written by author Robert Hilburn, the former music editor of The Los Angeles Times.

Hilburn tells the complete story of Johnny Cash for the first time. Of the many great rock and country arrivals in the 1950s, Cash was one of the few who approached his music as more than hits for the jukebox. He wanted to inspire and uplift people. As Hilburn illustrates, Cash was the crucial link between Woody Guthrie’s music of social idealism in the 1930s and 1940s and Bob Dylan’s music of revolution in the 1960s and beyond.

Singing of love, loss, hardship and faith, Cash was one of the first artists to recognize that he could use his music and fame to impact social attitudes, and offer hope to those downtrodden by society.

Hilburn shares a trove of never before seen material, straight from the singer’s inner circle of family and friends.

Roy Trakin, the esteemed writer and pop culture pundit in his Train Care of Business column displayed at www.hitsdailydouble.com gives kudos to Hilburn’s thoroughly researched tome “that manages to fuse the personal with the musical, It’s no hagiography, either, as Bob chronicles the man’s legendary drug abuse, stormy personal life and self-destructive behavior through a larger-than-life career that fills every one of those pages. Hilburn’s populist, plainspoken style turns out to be the perfect way to tell the story of this American icon, a grass-roots egalitarian, self-taught thinker and voracious reader, much like the man recounting his story.”

As Hilburn writes: “Cash’s life was often a struggle between his artistry and his addiction. But through Cash I want to tell the story of the challenges and demands of artistry; how someone has to keep fighting for his vision – against record company and/or public disinterest at times – if he or she is to achieve something truly lasting.”

One the testimonials on the back cover of Hilburn’s book is supplied by Keith Richard, who wrote, “I listened to that stark unrelenting country as a kid. He was a hero of mine. I met him, finally, in a john at the Waldorf Astoria. He was taking a pee and I broke out into ‘Loading Coal.’ We both zipped up and sung the final chorus together. One of my most cherished moments. You don’t get much closer than that. Hilburn has written a brilliant story of an even more brilliant song writer, warts and all.”

Rosanne Cash also endorsed Hilburn’s task. “A definitive biography of my father that is excruciatingly honest, rigorously researched, and has the depth and integrity that the subject demands.”

Harvey Kubernik Interviews Robert Hilburn

Q: When did you first have the concept of doing a Johnny Cash book? Obviously I know you covered Cash’s career as a pop music critic for The Los Angeles Times for 40 years. Why did Johnny Cash always speak to you? You began your journalism career first as a country music reviewer.

Q: When did you first have the concept of doing a Johnny Cash book? Obviously I know you covered Cash’s career as a pop music critic for The Los Angeles Times for 40 years. Why did Johnny Cash always speak to you? You began your journalism career first as a country music reviewer.

A: That’s true. I wanted to write about pop music in the late 1960s and contacted the Los Angeles Times and they gave me some free-lance assignments. One of them was going to Folsom Prison in 1968 to cover what turned out to be John’s landmark concert. I felt an immediate rapport with him, partially because we both came from small towns in the South (in my case it was the Natchitoches –Campti area of central Louisiana) and we talked a lot about what it was like transitioning to a larger world. After I was hired by The Times, I continued to do stories on John from time to time—including an interview at June’s childhood home in Virginia—just months before her death. I didn’t think about a book until after John’s death when I saw the movie and read some books about him and realized how much more there was to say.

Q: Take me through the process of having this book pitched to publishers. What were some of the responses your literary agent was telling you on the first submissions and publishing world feedback? Was it always planned to coincide with the tenth anniversary of his physical passing?

A: There was strong, immediate reaction to the proposal. The idea of timing it to the 10th anniversary of John’s death only came up later. I didn’t have it on my mind at the start.

Q: Take me through some of the research process? How do you first even tackle a Cash book and starting it?

A: I actually started researching the book before I wrote the proposal. I wanted to find out as much as I could before we approached publishers I signed with Little, Brown and Company early in 2011, and my plan was to spend the rest of 2011 researching the book, then all of 2012 writing it. As it turned out, I started writing in the summer of 2011 because I could see the story growing and I didn’t want to run out of time before my Jan. 1, 2013 deadline. We initially talked about 150,000 or so words and the manuscript eventually grew to 250,000 or so.

Q: Besides decades of trust and reporting of Johnny Cash, from being at the Folsom Prison live recording in 1968, and later in attendance at some of his last ever shows, why do you think the inner circle of Cash and his family opened up to you?

A: I think it was because they knew I had a long association with John and his manager, Lou Robin. It wasn’t like a stranger coming into the Cash world. But even with my long association with John, it was hard to get a few people to talk because they were, in a sense, gun-shy. They had been interviewed so many times since John’s death and they didn’t always like the way their observations were presented. It took, for instance, a year before Marshall Grant agreed to an interview. But I did see him and he was invaluable in helping me understand, among other things, the Sun Records timeline. Things went so well that we were planning to get together a second time, but Marshall died before we were able to do it.

Q: You covered Johnny and June for the paper and saw them perform countless times. You had some archive interviews. Did you start with a self-designed outline? Was chronology always a factor?

A: Absolutely. I wanted to do a formal autobiography….which meant starting from the beginning rather than trying to take some dramatic incident and make that the first chapter. I noticed that most serious biographies start at the beginning and I wanted the book to serious, though always readable. I think Cash is an enormously important artist and social icon. I wanted to treat him the way historians treated major figures. I wanted this to be able to sit on a “biography” shelf in a record store, not just a “music” shelf.

Q: What were the biggest challenges while researching and writing this book? Perhaps a wealth of available information?

A: The challenge, Harvey, was to simply get the story right. It’s a large, rich story, but so many people saw it differently. I had to wade through all sorts of conflicting accounts and try to figure out which one seemed to be most reasonable. That included John’s own statements. As he often said, “don’t let the truth get in the way of a good story”—or something like that. There was usually a germ of truth in what he said, but he tended to make the story more dramatic and that would often take it into a different place.

Q: You take us into the childhood of Johnny Cash. What were a couple of regional factors that might have shaped how his future music was made? Impressions from Depression-era Arkansas never left his soul. You present Cash as a link from Woody Guthrie to Bob Dylan on some level. Can you comment on this theory that the book underscores.

A: The thing that most interested me about John—all the way back to the 1960s—was his artistry. I can understand how someone like Bob Dylan or Bono gets a sense of artistry, but where did it come from in John’s case. Here was someone from a cotton farm in Arkansas, entering a country music field where nobody else in the 1950s had more ambition than another hit on the jukebox. But John, from the start, wanted to use his music to life people up. That grew out of his years in Dyess, Arkansas. The town was set up by the federal government as a way to help destitute farmers. Each family was given land to grow cotton. John saw how singing gospel songs in the fields helped make the day go by. He also saw the way people in the town worked together during hard times. And he saw how music in church lifted their spirits. He never lost that sense of music and an uplifting force…and he wanted to spread that word to everyone, especially people experiencing hard times. Though he wasn’t all that familiar with Woody Guthrie as a youngster (Jimmie Rodgers was his first musical hero), there were a lot of similarities between the way John saw music’s role and Woody’s way. It was the same link that Bob Dylan saw, which made it easy for Bob and John to bond musically in the 1960s. They both had enormous respect and affection for each other because they felt a kinship in their approach to music. Tom Petty, who worked with both, told me how amazed he was at how much musical history they both knew—tons of old blues and country songs, even English and Scottish folk ballads. I loved the album (now a bootleg) they made together in Nashville.

Q: After doing the book and through the journey, what strikes you more about the Cash records on Sun label than when you first heard them?

A: The quality of the best songs. As a teen-ager in the 1950s, I just liked Johnny Cash’s records because I liked the sound of them—as well as the drama of a song like “Folsom Prison Blues.” But now I can see what a great songwriter he was and how even then he was trying to forge his own path. Not always, he wrote a few songs strictly for the jukebox, but the best of the songs were extraordinary. I’m speaking of songs like “Hey, Porter,” “Folsom Prison Blues,” “I Walk the Line,” “Big River,” “Give My Love to Rose,” “Come in Stranger” and more.

Q: Your book also reminds us about his musicians like Marshall Grant and The Tennessee Two. Why did they click on tape and on stage with Johnny?

A: The remarkable thing about Marshall and Luther Perkins is they weren’t very good musicians at all. In fact, when John first went to see Sam Phillips, he went as a solo artist. He didn’t think Marshall and Luther were good enough to impress Sam. It was Sam who heard something he liked in their sound…that boom-chicka-boom style, which was very primitive, almost like using one finger at a time on a typewriter. They came up with that sound because they couldn’t do any better. But it happened to be a marvelous sound and it framed John’s vocals perfectly. John used to get frustrated at times because Luther couldn’t go in new directions on the guitar, but he finally realized what he had in Luther and Marshall and he was grateful for them.

Q: While doing the book, and examining his Columbia Records catalog, the book sort of reinforces that once Johnny had hit records he could do a variety of different albums for the label.

A: Yes, one of the big reasons John left Sam Phillips for Columbia was he wanted artistic freedom, which is something Columbia promised—and it eventually came back to  haunt the label because they wanted hits and that wasn’t the primary thing on John’s mind. Again, he wanted to make music that lifted people up—music that reflected his fascination with people and their struggles; hence so many songs about the Old West and the working man and Native Americans. John wanted to make music that mattered to him; Columbia wanted hits. The issue came to a head in 1963 when his Columbia contract was due to expire. Columbia was going to drop him, but Don Law, who signed John and produced his records, talked them into one more session. They came up with “Ring of Fire” and Columbia did renew the contract. If he hadn’t come up with a hit in that session, Columbia, in fact, would have dropped Johnny Cash.

haunt the label because they wanted hits and that wasn’t the primary thing on John’s mind. Again, he wanted to make music that lifted people up—music that reflected his fascination with people and their struggles; hence so many songs about the Old West and the working man and Native Americans. John wanted to make music that mattered to him; Columbia wanted hits. The issue came to a head in 1963 when his Columbia contract was due to expire. Columbia was going to drop him, but Don Law, who signed John and produced his records, talked them into one more session. They came up with “Ring of Fire” and Columbia did renew the contract. If he hadn’t come up with a hit in that session, Columbia, in fact, would have dropped Johnny Cash.

Q: Love, loss and hardship are constant themes in Cash’s records. As you listen to them and wrote about him for this book do you have a premise why they show up in his lyrics?

A: That’s easy. John wrote about what he felt and what he saw—and those these were constant in his life. He felt bad about walking away from his family, he never got over the loss of his brother Jack during childhood, and he faced hardships (from drugs to, later, constant illness) much of his life. That suffering also gave John great empathy for other people. He could see their hardships and, again, he tried in his music to give them hope.

Q: Johnny lived for many years living in Ventura County and then Encino. For decades, books and articles really minimize his years in California. Johnny was always on Town Hall Party, a TV show done in L.A. And, Johnny Cash brought a country music show to the Hollywood Bowl. In 1957 at a party in California Johnny first met British-born record producer Don Law who first suggested to Johnny that he join the Columbia label after his contract with Sun expired on August 1, 1958. Johnny Cash Enterprises was located on Sunset Blvd. at the Crossroads of the World complex in Hollywood.

A: Johnny moved to California in 1958 because he wanted to go into the movies like Elvis and he wanted to separate himself from the conventional thinking of Nashville, the center of country music. He bought Johnny Carson’s old house in Encino, just down the street from where the Jackson Family eventually set up its compound. John had some happy years in Encino, but gradually things started going bad. His film debut—in a low budget crime story called “Five Minutes to Live”—was embarrassing, a real disaster. And tensions developed between John and his wife, Vivian, over the career demands that took him away from home so often. Then, the drugs took hold. Looking for a new start, he moved to a small town in Ventura County to escape the glare and pressure of Hollywood. But the tensions and drugs continued. He pretty much stopped coming home. By early 1966, he had pretty much left California and the family behind. He moved to Nashville and spent most of his time with June Carter.

Q: Cash and June were public people in faith and religion. Their involvement with the Rev. Billy Graham. That aspect of his life is in your book. Why was faith and religion so important to him? Cash even made specific records or TV shows for that marketplace.

A: As a boy, John wasn’t like most kids who complain about having to go to church. He loved it—the music, the sense of community, his mother’s devotion. Religion was very real to him, and he never lost his faith. He didn’t go to church a lot as an adult because of the commotion it would cause when he walked into the church, but he sang one or more of his mother’s hymns to himself virtually every day. That was his form of prayer. Meeting Billy Graham was a huge factor in John’s life, because he often worried that he wasn’t a good Christian—given the drugs, the infidelity, the vanity—and Graham reassured him and encouraged him.

Q: Before Johnny Cash met June Carter he was a wild child, missing shows and a pariah in country music circles. Were you even amazed about the early missed shows, the addiction to pills that should have hampered his career a lot more? Your book examines this era. But is it is amazing he had a long career?

A: Well, he wasn’t alone in missing a lot of shows. There were lots of country music greats who had a history of missing shows or showing up drunk/stoned, dating all the way back I believe to Hank Williams, one of John’s heroes. Remember, John toured a lot with George Jones in the early days, and George was notorious for no-shows. Country music audiences loved them anyway; they were very accepting of their heroes’ vices.

Q: What things or realities kept emerging as you researched the life of Cash? Or what really impressed you along the way that needed to be in the book. You seem to stress that he wanted to take country music out of the jukeboxes and into the global stage.

A: Again, what impressed me time after time was his drive to make music that mattered…music that would lift people’s spirits…even though he’d be going through incredibly hard time emotionally.

Q: Yet, Johnny Cash also demands and is determined to release LP’s like Bitter Tears. Why was this album so difficult to market? Cash and a pal, Johnny Western, promoted it out of an office on Western Ave. in Hollywood. Author Antonio D’Ambrosio wrote the book A Heartbeat and a Guitar about Bitter Tears.

A: At the time Cash was making concept albums like Ride This Train and Bitter Tears in the 1960s, the country music world (chiefly radio) was focused on hits. They weren’t looking for “art” from their singers. But rock ‘n’ roll changed that. Thanks to people like Dylan and the Beatles, fans began to look for “art” as well as “hits” and they began buying albums rather than just singles. Cash tapped into that with the Folsom Prison album, and he found an audience that didn’t just listen to country radio. He was embraced by the rock culture, and I think it’s that audience finally discovered Cash’s “art”/concept albums.

Q: Cash managers Saul Holiff and Lou Robin are in your book. How important were they in guiding Johnny Cash?

A: Saul and Lou played totally different roles. Saul’s big contribution was helping John move from the country world to a larger pop-country stage. Saul brought him to Carnegie Hall and the Hollywood Bowl and the Newport Folk Festival. He urged John to widen his horizons. At the same time, he was strong enough to battle John’s demons—sticking with him when most managers (because of the drugs and no-shows) might have jumped ship. But they parted ways for various reasons. Lou then stepped in and he did a marvelous job of keeping the ship going, through more bouts of drugs and turmoil. Lou was also loyal, sticking with John when the sales slipped so much Columbia Records dropped him. Even then, Lou did a great job of making John look like and feel like a star. It was a warmer relationship than the one between John and Saul.

Q: Can we talk about the Johnny Cash TV series 1969-1971? How seminal was it in exposing musical talent? The Everly Brothers, Tony Joe White, the Monkees, Roger Miller, Judy Collins, Marty Robbins, Loretta Lynn and others were among Johnny’s personally invited guests.

I interviewed Johnny in 1975 for Melody Maker and he told me that his TV series somewhat hampered his creativity. “It cut down on my touring, it became too confining. If it was kept loose and spontaneous it could have been great. But we had to do the same song every eight or ten times before they would accept it. The show lost its feel and honesty. Consequently I lost a lot of interest in it.”

A: Though he was often frustrated by some compromises forced on the show by the network, Cash used the show to express his core values. He brought on musical guests he believed in—not just Bob Dylan, but also Merle Haggard, Kris Kristofferson, Waylon Jennings. He used the show as his pulpit, if you will, to once again lift people’s spirits. He sang lots of songs about small town America and lots of gospel songs. Three tunes—“Man in Black,” “What is Truth” and “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down”—largely defined Cash for a mass audience, and he became a national icon. People didn’t just like John’s music; They believed in him. The timing was crucial. If he had gotten a TV show just two years earlier, it would have been a disaster. America would have seen a desperate drug addict. Instead, they saw a national icon.

Q: During my 1975 discussion with Johnny for Melody Maker we also talked about Bob Dylan. Cash remembered the first time he became aware of Dylan with the release of his Freewheelin’ album. Columbia Records A&R man, John Hammond, sent Cash an advance copy in late 1961.

“I thought he was one of the best country singers I had ever heard. I knew he had heard and listened to country music. I heard a lot of inflections from country artists I was familiar with. I always felt a lot in common with him. I was in Las Vegas in 1963 and ’64 and wrote him a letter telling him how much I liked his work. I got a letter back and we developed a correspondence. We finally met at Newport in 1965. It was like we were two old friends. He’s unique and original. I respect him. Dylan is a few years younger than I am but we share a bond that hasn’t diminished. I get inspiration from him.”

A: Bob has told me time and again how much he loved John’s music and his failure to compromise. The bond was so great between then, even though they didn’t spend a lot of time together. Their relationship was more one of mutual inspiration and respect than time spent in each other’s company.

Q: The movie Walk The Line took a Hollywood screen angle, but what did you observe about the Johnny and June couple in person or on stage that made that partnership work?

A: Marshall Grant told me that if there’s a hero in the Johnny Cash story, it has to be June. John didn’t always treat June nicely; Their relationship was stormy in the 1960s and again in the 1970s and early 1980s. June stuck by him because she believed in him and she thought the bad times would pass. Their relationship has usually been presented as a “fairy-tale” existence, but it wasn’t really until late in their relationship that you could apply the words “fairy-tale” in any consistent manner. At the end, however, it was a grand love indeed.

Q: All the Cash relatives and children participated in this book with you. What were these interviews like? Were some forthcoming while others guarded? There is so much documentation available on Johnny. Did they want to give you something different and be accessible?

A: Some of the relatives were very guarded; they only wanted to see John’s life in rosy terms. But a strong core of the relatives, including John Carter Cash and most of the daughters, wanted the full, accurate story told. Rosanne was particularly strong on that point. I made it clear the book itself would be totally my judgment. No one had any sort of veto power.

Q: Record producer Bob Johnston is an important figure in Johnny’s records on Columbia since 1967. Bob’s recording methods had impact on Johnny. Johnston informed me in a 2007 interview, “When I took over Cash he didn’t hit the country charts. No one for eight years would let him go to Folsom Prison to record live until he got me. And I said, ‘let’s do it.’ I picked up the phone and called Folsom and San Quentin. When we did Folsom I told Johnny to go walk out there on stage and jerk your head around and say, ‘Hello. I’m Johnny Cash.’ And he replied, ‘Get outta my God damn way!’ And he didn’t usually cuss. But he pushed people away, went out there and the God damn place went unglued.”

A: I spent a lot of time with Bob and I believe he deserves an enormous amount of credit for the Folsom Prison album and some of the other albums he did with John. He not only helped John believe in himself at a time when the drugs and other problems had left him vulnerable, but he organized the Folsom tracks and San Quentin tracks in a way that maximized their impact.

Q: Can you discuss the Cash and Kris Kristofferson friendship and recording collaboration. Kris will join you on October 29th in Los Angeles for a conversation about Cash and your book presented by the Writers Bloc Presents series, a program founded by Andrea Grossman.http://writersblocpresents.com/main/robert-hilburn-with-kris-kristofferson-on-johnny-cash/

A: John was one of the reasons Kris wanted to move to Nashville and pursue songwriting. Kris also found John a fascinating subject for some of his songs, including “To Beat the Devil” and “The Pilgrim Chapter 33,” which is as compelling a portrait of John as you can find anywhere. The interesting thing is how long it took John to actually record one of Kris’s songs. John took an immediately liking to Kris, but he didn’t seriously think about recording a Kris song for years. He had known and passed on even “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down” for a long time before finally recording it, and the song seemed perfect for John. Once he started believing in Kris, however, John loved his music and took every opportunity to record another Kris song. He even took Kris with him to Newport one time to help Kris find a bigger audience. Their friendship was profound and deep.

Q: The legacy and the myth of Johnny Cash have grown since his work with producer Rick Rubin and his American Records. Your book details the Trent Rezner-penned “Hurt” and subsequent Cash/Rubin studio collaboration and the well-played video of the song.

I interviewed Rubin in 2009 around the time I did a book on the music of Laurel Canyon. Rick at the time described the process of how he and Johnny picked songs to cut. “Johnny and I would exchange CD’s of ideas of what songs to record. Sometimes I’d feel stronger about some songs than others. And he would say, “I think I want to do these three.’

“Trent Rezner didn’t hear ‘Hurt’ until it was done. Maybe even when the record was out I sent him a copy. His initial reaction was not great…Just because it’s just a personal song to him and it freaked him out a little bit when he heard it. Then I sent him the video and when he saw the video he freaked out and loved it. The video made him understand it.”

What did Rubin deliver besides getting Johnny back on the charts?

A: One of my favorite quotes in the book is about Rick—from Rosanne. Rick entered John’s life at a time when he had lost all of his confidence. He not only thought his recording career was over, but he also feared that he had blown his legacy with years of indifferent, poorly received albums. Rick’s first challenge was rebuilding John’s confidence about his music and about his future. Rosanne’s quote, “I think Rick saved his life at that moment. Well, maybe ‘saved his life’ is too strong, but….maybe not.”

Q: What is the world of Johnny Cash? I do realize many Cash fans and record collectors first became aware of him from the “Hurt’ record and video. There is a younger demographic buying his catalog.

A: That’s true about younger fans learning about him from “Hurt.” In fact, W.S. Holland, John’s long-time drummer, said something that surprised me. Realizing the tremendous emotional impact of the “Hurt” video, he said, “You know, Johnny Cash may someday be known more for that video than the records we made.” And there may be an element of truth to that, so I put a detailed guide to John’s recordings in the back of the book—so that someone who did come to John’s music via “Hurt” could have a blueprint to what was important before “Hurt,” but I also wanted the guide to be of help to someone who only knew John’s music from the Sun or Columbia days to pursue the best of his work with Rick. As for legacy, I think John—beyond the great music he left with us—pointed out the importance of an artist standing for something…not just making music for chart position. He always wanted hits, but he most wanted the music to have a meaning—to himself and his audience. That’s something he shared with a lot of people who followed him in country and rock, but it was pretty revolutionary for country and rockers in the 1950s. It’s also a lesson that is doubly important today, when so much of the music that does make it onto the airwaves and onto the charts seems to have so little meaning—other than simple entertainment. Johnny Cash wasn’t about simply entertainment. Like Bob Dylan, he belongs with the great American artists, whether they are from the worlds of art, film or music. He told about his life and times with a strong, personal vision.

Q: I imagine your first manuscript must have been two or three times as long as the final book we read. How did you approach editing the first draft? What are the secrets of editing?

A: Thank goodness, Harvey, the first draft of the book wasn’t two or three times as long. I didn’t have to go through the agony of cutting back on the text. I was conscious all along of telling the full story, but also not going off on tangents that I didn’t feel were essential to the reader’s understanding of Johnny Cash. So, I was very careful about keeping the story concise. I felt the over-telling of John’s story would be as big a mistake, if you will, as under-telling. So the original manuscript was probably around 253,000 words, which I thought was a touch long., so I went back and trimmed around 18,000 words from it. I was open to trimming even more if John Parsley, my excellent editor at Little, Brown, recommended it, but he was pleased with the length. In fact, we may have ended up adding a couple thousand words.

Q: What is your most enduring and endearing memory of interviewing Johnny Cash and what were the circumstances?

A: The overriding memory was his graciousness—June as well. John wasn’t a very outgoing person and June helped him a lot by taking on the so-called “social” responsibilities of stardom; the greeting of people backstage, etc. But when you got him alone, John was so warm, so thankful for his blessings in life.

Q: Can you also suggest a few hidden recording gems of Cash we should investigate besides the hits and the tunes we hear on the radio and documentaries?

A: That was one of the most enjoyable aspects of writing the book—going back and listening to the dozens of albums and discovering things I may have missed or forgotten. I also enjoyed many hours of listening to the music of two of John’s personal favorites: Jimmie Rodgers and Sister Rosetta Tharpe.

Of John’s own recordings, a few things stand out from the latter years. One was a song he recorded during his brief spell on Mercury titled “The Night Hank Williams Came to Town.” It was co-written by Bobby Braddock, who co-wrote “He Stopped Loving Her Today.”

There were also a couple of great songs John wrote while under contract to Mercury in the late 1980s/early 1990s, but he didn’t want to put them on a Mercury album because he knew they’d get lost. Country radio had forgotten about him by then and Mercury wasn’t promoting his albums. But he played them for Rick Rubin and Rick loved them. So, he put them on the American Recordings album: “Like a Soldier,” a wonderful summation of his life and regrets,” and “Before My Time,” a sweet, tender love song.

Also, there’s a magnificent recording that many Cash fans may not know: “The Wanderer,” a modern gospel tale that he recorded in Dublin with U2. It was on the Zooropa album. Finally, there’s another song John recorded with Rick Rubin soon after he learned June was dying. It was his version of Larry Gatlin’s “Help Me,” a spiritual plea for help. To Rick, it’s probably John’s most moving vocal. And there is so much more. With most artists, the appeal of the music wanes once you get past the hits. With Johnny Cash, the music often tends to get richer beyond the hits.

Still can’t get enough of Johnny Cash?

Highly recommended is the 2 disc DVD set The Best of the Johnny Cash Show the 1969-1971 ABC-TV series distributed by CMV/Columbia Legacy, a division of Sony BMG Music Entertainment.

The William Carruthers Company first produced the groundbreaking Cash series in 1969 while Bill Carruthers, who earlier directed the memorable Soupy Sales television show, helmed the first season.

The Johnny Cash Show debuted in June 1969. Episodes were filmed at Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium, which back then was home to the Grand Ole Opry.

58 episodes were originally broadcast and the 2007 four hour DVD compilation integrates highlights and compiled performances. Doug Kershaw, Arlo Guthrie, Odetta, Guess Who, Roy Orbison, , George Jones, Tammy Wynette, Joni Mitchell, Ray Charles, Derek & the Dominos, Charley Pride and Conway Twitty are in the package.

Kris Kristofferson hosts the DVD. The 2007 DVD restoration process was produced and directed by Michael B. Borofsky. Editor and Producer Is Christine Mitsogiorgakis. Executive Producers are Lou Robin, Cash’s longtime manager, and John Carter Cash, his son with June Carter Cash.

The DVD incorporates the 66 clips, plus new interviews with Tennessee Three bassist Marshall Grant, Hank Williams Jr., musical arranger Bill Walker, and hairstylist Penny Lane. The show’s regulars included Johnny and June Cash, the Tennessee Three, Mother Maybelle and the Carter Sisters, Carl Perkins, and the Statler Brothers.

“The sound jumped off the screen on the Cash TV series,” recalled record producer Bob Johnston to me in a 2007 interview. “Everything I said and did was for the artist. I never gave a fuck what the company thought. One of my goals was to make it sound like they were in the room with me. But the thing I wanted was the truth. And that’s what Cash got. At the Ryman Auditorium tapings for the Cash show I was always real nice to everybody and had two engineers from Columbia (Records) in Nashville that I told Cash we had to have with them so they didn’t fuck up for us,” explained Johnston. “Johnny didn’t fight for anything. ‘This is the way it’s gonna be.’ I had those people take care of everything and anything that was bad I would move it, and anything that wasn’t I’d re-record it on the kind of microphone I’d want and put it on there anyway.

“When we got through with Dylan’s Nashville Skyline and the Cash and Dylan session, I helped Cash get his TV show,” Johnston volunteered. “Cash called me a little bit later, and said, ‘Listen. I got one thing. ‘Will you get Dylan? If I had Dylan on my show it would be a big success. And if I don’t it will be a fuckin’ failure. Will you get him?’ And I said, ‘No.’ ‘You won’t?’ ‘No.’ ‘Why not?’ ‘But I’ll ask him. But I can’t get anybody. I don’t want to get anybody.’ That’s the kind of truth I had with all of those people. Cash said, ‘will you ask?’ ‘Yes.’

“So, I was in Ft. Worth Texas, which was my home town, and called Dylan. And I said, ‘Man, Cash just called me and he’s got a TV show that we’ve been working on and if he’s got you it will be a success and if he doesn’t it will be a fuckin’ failure. That’s what he told me.’ And, Dylan said, ‘Well, man, I’d like to…’ And I thought that’s the end of that, he’s so busy… And he said, ‘I’ve got nothing to wear.’ I mentioned, ‘I’m in Ft. Worth Texas. Let me get you a cowboy suit.’ ‘Yeah!’ ‘What size do you wear and what color?’ ‘I don’t know.’ I said, ‘don’t fuckin’ worry about it I’ll take care of it.’ I got him a pin stripped white one that was too long came over his wrist, and a white one that was too short. That’s how it started.”

Interestingly, Johnny Cash’s son, John Carter Cash, a music producer and an Executive Producer on the Cash film biography Walk The Line movie, and also an Executive Producer on the Cash 2007 TV series DVD, told an amusing story describing Bob Dylan’s initial encounter with his dad in the December 2, 2005 issue of USA Weekend. “Dad would chuckle when he’d tell me how Bob Dylan acted like a silly kid when they first met. He burst into Dad’s hotel room and began jumping on the bed, shouting, ‘I met Johnny Cash! I finally met Johnny Cash!’”

Los Angeles native Harvey Kubernik has been an active music journalist for over 40 years and the author of 5 books, including “This Is Rebel Music” (2002) and “Hollywood Shack Job: Rock Music In Film and On Your Screen” (2004) published by the University of New Mexico Press.

In 2009 Kubernik wrote the critically acclaimed “Canyon of Dreams The Magic and the Music of Laurel Canyon” published by Sterling, a division of Barnes and Noble. In summer 2012, the title was published in a paperback edition.

He is also a writer of “That Lucky Old Sun,” a Genesis Publications limited edition (2009) title ($900.00 signed ) done in collaboration with Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys and Sir Peter Blake, designer of the Beatles’ “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” cover.

With his brother Kenneth, he co-authored the highly regarded “A Perfect Haze: The Illustrated History of the Monterey International Pop Festival” published in 2011 by Santa Monica Press. They have also teamed up for a book with photographer Guy Webster for Insight Editions, slated for summer 2014.

For early spring 2014, Harvey Kubernik’s “Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll in Los Angeles 1956-1972” will be published by Santa Monica Press.

In fall of 2014, Palazzo Editions will publish “Leonard Cohen: Everybody Knows,” a coffee table size volume with narrative and oral history written by Harvey Kubernik.

This century Harvey penned the liner notes to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s “Tapestry,” Allen Ginsberg’s “Kaddish,” the “Elvis Presley ’68 Comeback Special” and the Ramones’ “End of the Century.”

He is the Contributing Editor of Treats! Magazine and Record Collector News.

In 2013, Kubernik was seen on the BBC-TV documentary on Bobby Womack, “Across 110Th Street,” directed by James Meycock and lensed for the upcoming Neil Norman-directed documentary about the Seeds.