By Harvey Kubernik c 2017

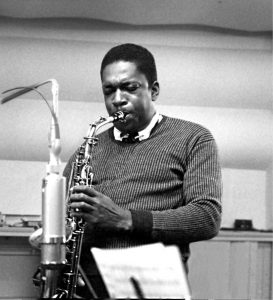

Saxophonist John Coltrane died on July 17, 1967 in Huntington Hospital in Huntington, New York in Long Island after a brief bout with liver cancer.

“Mourned by as many rock musicians as those from the jazz world, he was a courtly, soft-spoken gentleman from North Carolina, who pursued the roiling, labyrinthine currents of improvisation, from the postwar abandonment of big-band swing in favor of the fractious sounds of bebop and beyond,” observed keyboardist and author Kenneth Kubernik.

“In each step of his evolution, beginning with Dizzy Gillespie’s orchestra, through his tenure with Miles Davis and his own stentorian ‘classic quartet,’ Coltrane revised and refined his ‘voice,’ a burnished, muscular tenor, liquidly velvet on ballads, coruscating on up-tempo numbers.

“Coltrane recognized that music’s capacity for astonishment, for both the performer and the alert listener, was much more than diligent practice—his fearsome virtuosity would often lead him into thickets of stifling verbosity, as off-putting as an electric guitar’s noxious feedback. The sounds he heard in his head—the quest for pure intent—compelled him to eschew the Great American Songbook, that litany of Broadway standards that were long the heart and soul of jazz, for an unforgiving ascent into cacophony.”

Just before Coltrane’s physical departure, he had been scheduled to participate in a jazz festival at UCLA’s Pauley Pavilion in Westwood, a European tour in October, and then a trip to Africa to study music.

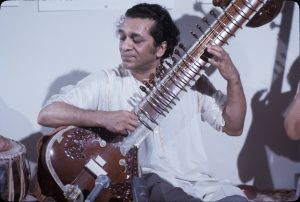

“He was coming to learn from me,” revealed Ravi Shankar in a 1997 interview I conducted with him for HITS magazine inside his Encinitas, California home. “I told him, ‘John, why do I find so much turmoil and disturbance in your music?’ He laughed and said, ‘That’s exactly what I’m trying to find out myself, and you can help me.’

“We had three meetings, and he came and sat twice, a very long one and a very short one in a New York hotel where I used to stay. And he wrote down many ragas, and I taught him how we improvise, and he was asking me, ‘How do you bring the spiritual quality in your music? How do you do that?’ Afterwards, he started using more drones, if you remember. I heard the turmoil in his music. He was like a child. It was a wonderful revelation for me to see this man. Dick Bock [Pacific Jazz Records] always tried to play me as much Coltrane as possible, in the car, or a few records. There I was hearing certain melody qualities that were so wonderful,” Ravi enthused.

“In 1967 the best record I listened to might have been John Coltrane’s Africa Brass,” suggested Byrds’ co-founder Roger McGuinn to me in a 2007 interview.

“We were on the road, and I had bought a Phillips Cassette Recorder in London, and it was such a new invention at the time there were no pre-recorded cassettes on the market. But, I had a couple of blanks that I picked up. And we stopped somewhere in the mid-west, [David] Crosby knew somebody there, so we went over to this guy’s house, and he had the latest Ravi Shankar and Africa Brass.

“And, so, I guess this is music piracy, but I dubbed Africa Brass on one side of the cassette and Ravi Shankar on the other. And we strapped the cassette player to a Fender amp on the bus and we just kept turning the cassette over and over and listened to that thing for a month on the road. We loved that music, which influenced ‘Eight Miles High’ later. The break on ‘Eight Miles High’ was a deliberate attempt to emulate Coltrane, like sort of a tribute to him, if you will.

“We had heard Ravi Shankar earlier,” McGuinn recalled. “I had a physical response to that Coltrane album the first time I heard it. It felt like a white hot poker was searing through my chest. It cut deep into me and it was a little painful. But I loved it. It just opened up some areas in my heart and head that I hadn’t known about.

“I think what I loved about Africa Brass was the improvisation of course, but his attitude comes through. A forceful, rebellious attitude. Like rock ’n’ roll. It really knocked me out.”

“In 2007 I heard a recording of the Miles Davis Quintet in the fall of 1967 from the University of California at Berkeley in the Harmon Gymnasium,” recollected drummer and percussionist Jim Keltner in a home interview we did last decade.

“This Miles Davis 1967 show in Berkeley confirms the legend that has built up around him. As if it needed confirming. ‘7 Steps To Heaven’ and Tony Williams drumming changed my whole life.

“It was changed earlier when I saw Elvin Jones with John Coltrane when they came to town at Club Renaissance. Those are the two strongest events I’ve ever seen musically in my life. Miles with Philly Joe, Paul Chambers and those cats at the Renaissance Club.”

“I saw [Jimi] Hendrix in 1967 at the Whisky just after the Monterey International Pop festival,” John Densmore, drummer of the Doors told me in a 2007 telephone interview.

“God! We knew somebody was coming. A giant! It was just…I don’t have the words…He was like Coltrane on guitar, playing it upside down, without changing the strings. Forget it.

“I saw Coltrane many times. I was a jazz snob until I heard the mop tops music and I went, ‘They’re cute.’ And then I got into rock ‘n’ roll. I saw every jazz great who ever came to town the first half of the 1960s. Les McCann at the Renaissance Club. Cannonball Adderly at Howard Rumsey’s Lighthouse. Bill Evans five or six times at Shelley’s Manne Hole. I shook his hand.

“Hearing jazz I first started with Dave Brubeck. Then, I saw Les McCann, blues and funk, Miles [Davis] and John Coltrane. At Valley State College one of the ethnological music instructors was Fred Katz, who was the cello player for the Chico Hamilton jazz quintet.

“I noticed with Elvin Jones and John Coltrane there was communication. So, I thought, ‘I’m gonna keep the beat. That’s our job as drummers. But, I’m gonna try and talk to Jim [Morrison] during the music.’ Like, ‘When the Music’s Over.’ That’s Elvin. I knew I wasn’t playing jazz.”

“In the early sixties in New York I saw Miles Davis, Charles Mingus and John Coltrane in New York,” exclaimed Ray Manzarek, co-founder of the Doors to me earlier this century.

“‘During the ‘Light My Fire’ solo section it’s an A-minor triad to a b-minor triad that just repeats like John Coltrane’s version of ‘My Favorite Things.’ The same modal chord structure that I used in ‘Light My Fire.’

“Left-handed I’m playing the same thing over and over. The right hand is just playing behind [Robby] Krieger, punctuating with chords, punctuating with single notes playing with Krieger. When I’m soloing I’m playing anything I want to play. And that bass line just keeps on going. Like tribal drumming or Howlin’ Wolf playing one of his songs without any chord changes on and on and on. The same pattern. The same three notes over and over. And off he goes, man.”

“Ray Manzarek is the ‘forgotten man’ in the history of jazz-rock fusion,” stated Dr. James Cushing, who hosts the program Jazz Classics on KEBF-FM in Morro Bay, California. “Months before Miles Davis began experimenting with electric keyboards, and years before The Tony Williams Lifetime, The Doors’ organ-guitar-drums trio sound opened secret passageways between rock and jazz.

“I had no idea, as a 1967 teenager freshly arrived in LA, that I was listening to a variation on John Coltrane’s ‘My Favorite Things’ as I grooved on the far-out ‘album version’ of ‘Light My Fire,’ nor did I connect ‘When The Music’s Over’ with its source in Herbie Hancock’s ‘Watermelon Man.’

“I think that the death of John Coltrane the same summer Jimi Hendrix emerged marked a fundamental change in what was happening in music,” Cushing offered. “John Coltrane was second only to Miles Davis as being the most charismatic and important man in jazz. He and Miles were the guys. And Coltrane was in his wildest, freest period.

“Talk about the ‘grand permission!’ Free jazz was the wildest permission of them all. Coltrane’s music was way beyond psychedelia. Coltrane’s death represents a road prematurely closed off.

“I think Coltrane’s death also, at least historically, marked a transition: after 1967, jazz, at the most fundamental level was no longer at the center of the intellectual life of young American listeners.”

‘“I want to be a force for good,’ said John Coltrane,” reiterated musician, music journalist and jazz scholar Michael Simmons. “A statement like this would be considered ridiculously utopian by many here in The Twenty-Worst Century, a time in which greed and cynicism and self-gratification are permissible — even laudable. But there are reasons why Trane is Trane and no one else is.

“As a musician he mastered technique, exploding with energy and heart and possessing an immediately identifiable sonic signature. And like all geniuses — a relatively small bunch — he had a transcendent and largely ineffable component. His desire ‘to be a force for good’ is part of it — the rest can’t be put into words because it belongs to the superior language called music. To understand it, there’s only one option: listen to the recordings.”

This past spring, the Abramorama company handled the North American theatrical distribution of John Scheinfeld’s documentary Chasing Trane: The John Coltrane Documentary. A DVD is scheduled for last quarter 2017 retail outlets.

The film played to critical and audience acclaim in the fall of 2016 at its world premiere at the Telluride Film Festival and also at the Toronto International Film Festival, IDFA and DOC NYC. Set against the social, political and cultural landscape of the times, Chasing Trane brings John Coltrane to life as a fully dimensional being, inviting the audience to engage with Coltrane the man, Coltrane the artist. Featuring interviews with Wynton Marsalis, Sonny Rollins, Dr. Cornel West, President Bill Clinton and Common, among others, Coltrane’s own words are spoken by Denzel Washington.

Written and directed by documentary filmmaker John Scheinfeld who previously directed and wrote the screenplay to Who Is Harry Nilsson (And Why Is Everybody Talkin’ About Him?)

The film was produced with the full participation of the Coltrane family and the support of the record labels that collectively own the Coltrane catalog.

Although Coltrane did not do any television interviews during his lifetime…and only a handful of radio interviews, he has an active and vibrant presence in the film beyond remarkable performance clips through thoughts he expressed during print interviews. His words are spoken by Academy Award winner Denzel Washington.

“There is much to admire both in the music and in the man that was John Coltrane,” emailed singer/songwriter and trumpet player Sarah Kramer, who was awarded a Nesuhi Ertegun Jazz scholarship by trumpeter/composer Wadada Leo Smith with whom she studied at Bard College.

“…Coltrane’s technical skill(s) and versatile abilities in quite a range of styles is inspiring, but it is the sounds/style of his own voice that truly made and continues to make an impact in music both as a player and as a composer/arranger.

“I always cherish melody and groove, tone and voice… authenticity. He was a master of this, his approach in melody, motif and/or improvisation. It was a solo exploration, but also a collective endeavor with specific players, whether it be within his time with Miles Davis, or with the phenomenal array of players/voices he worked with on his own as well (Freddie Hubbard, Eric Dolphy and such a long list of others). His quartet with Elvin Jones, McCoy Tyner and Jimmy Garrison, resonates with me the most (the improvising, the searching/exploring, the discovering).

“The level of listening/musicianship was so deep, and the willingness to both support and to lead each other in a musical journey captivates the listener/audience in a hypnotic fashion. It commands in an inviting way.

“Coltrane’s love of the divine, that Love Supreme, his quest to delve into the spiritual, that is pretty mind blowing. His analyzing of the Circle Of Fourths (or Cycle Of Fifths) as symbols, shapes… stars; something higher, something deeper… finding harmonies and modes, textures, tensions, releases… it was as if he functioned on a whole other dimension. There was a certain mindfulness, a consciousness, a focus as a spiritual being.

“He could tell a story, express emotion, travel far and wide. I love to be a passenger listening to his tenor. It’s all about context though, the space and the other players, it’s all of the elements coming together, and we’re so lucky for the recordings that captured it.”

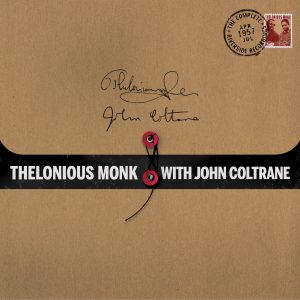

60 years ago, for an all-too-brief, magical time in 1957, two of the greatest musicians in history –Thelonious Monk and John Coltrane — performed together every night at New York’s Five Spot Cafe and between April and July of that year, they made their only studio recordings together.

On June 9th, the newly minted imprint Craft Recordings, reissued Thelonious Monk and John Coltrane’s Complete 1957 Riverside Recordings as a deluxe vinyl edition box set featuring new artwork, rare photos and 180-gram vinyl pressed at RTI from lacquers cut by George Horn at Fantasy Studios in Berkeley, CA. Remastered from the original analog sources, audio will also be released in hi-res digital formats.

The collection features such stellar musicians as Art Blakey, Wilbur Ware, Coleman Hawkins, Shadow Wilson, Ray Copeland and Gigi Gryce. Rounding out the package is an insightful essay by the late Orrin Keepnews, who, as producer of the original sessions, was present at the creation of every note.

Coltrane was poised to make a giant leap forward and ready to learn from one of the masters, Monk. In a DOWNBEAT interview Coltrane recalled, “Working with Monk brought me close to a musical architect of the highest order. I learned from him in every way.”

“The intersection of John Coltrane and Thelonious Monk in 1957 defines high quality and innovation, so it was an easy choice to have this unique package as Craft Recordings’ inaugural release,” reflected Sig Sigworth, President, Craft Recordings.

2017 marks what would have been Monk’s 100th birthday and this release celebrates the brief but prolific intersection of genius between two of jazz’s all-time luminaries.

(Harvey Kubernik has been a music journalist for over 44 years and is the author of 10 books. In April of 2017, Sterling published Kubernik’s now critically acclaimed book 1967 A Complete Rock Music History of the Summer of Love).