FESTIVAL 2CD/2LP RELEASED IN SEPTEMBER;

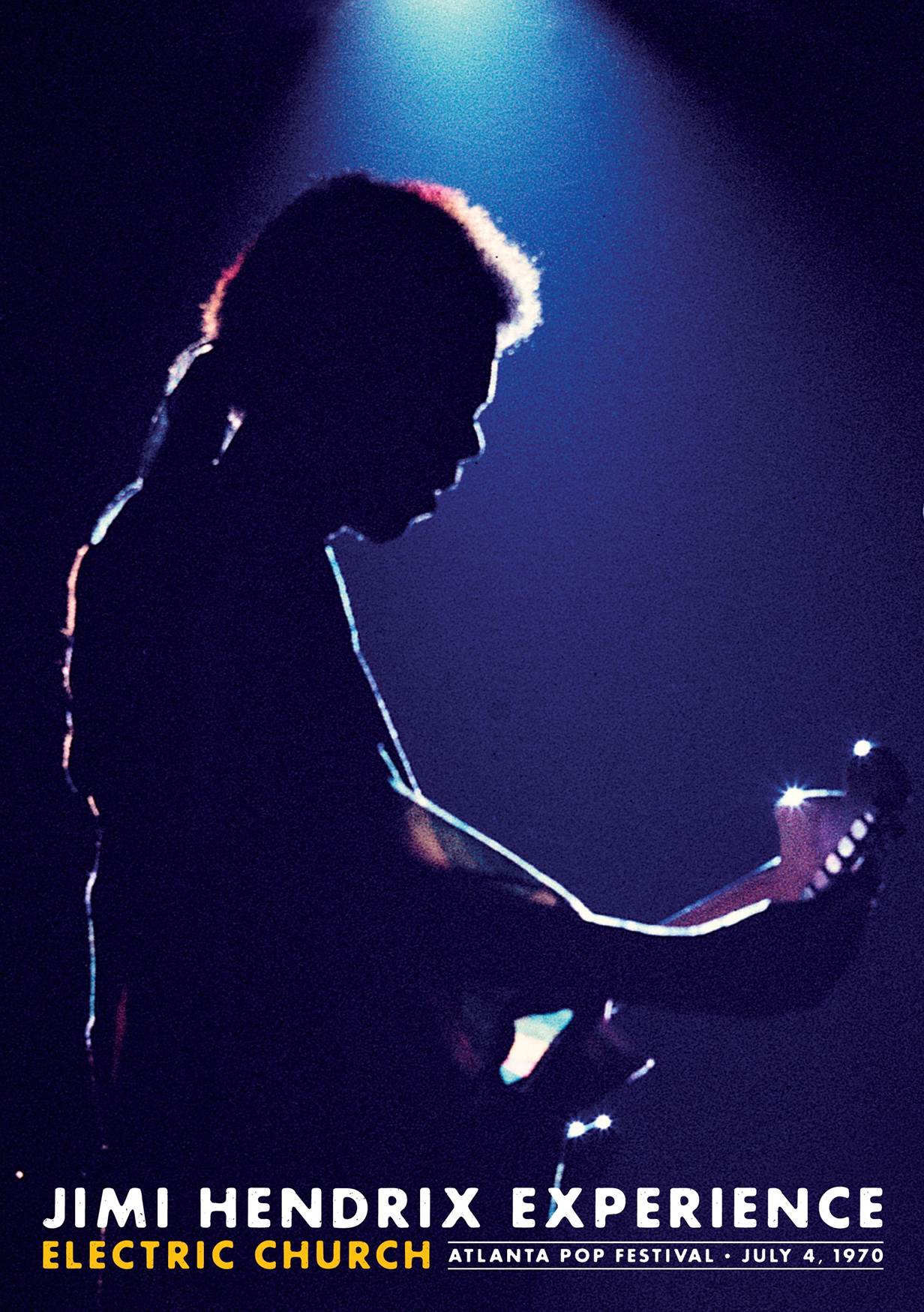

JIMI HENDRIX ELECTRIC CHURCH DOCUMENTARY DVD/BLU-RAY DUE ON OCTOBER 30th;

Billy Cox interview with Harvey Kubernik

By Harvey Kubernik c 2015

About 100 miles south of Atlanta, next to a field just outside the town of Byron, there stands a plaque erected by the Georgia Historical Society  marking the location of the Second Atlanta International Pop Festival, where from July 3-5, 1970, “Over thirty musical acts performed, including rock icon Jimi Hendrix playing to the largest American audience of this career.”

marking the location of the Second Atlanta International Pop Festival, where from July 3-5, 1970, “Over thirty musical acts performed, including rock icon Jimi Hendrix playing to the largest American audience of this career.”

Despite the overwhelming attendance (estimated to be 300,000-400,000), the festival and Hendrix’s performance in particular, has not received its due in terms of historic importance and impact until now.

The audio release Freedom: Jimi Hendrix Experience Atlanta Pop Festival, which Experience Hendrix L.L.C. and Legacy Recordings was issued in September. It includes six performances not seen in the Showtime documentary. This item is available as a 2CD set and also as a 200-gram 2LP vinyl set. The first 5,000 vinyl units are individually numbered.

Jimi Hendrix: Electric Church, a new documentary film about the music legend’s Atlanta Pop set and the circumstances surrounding it, debuted on SHOWTIME television this past September.

Experience Hendrix L.L.C. and Legacy Recordings, the catalog division of Sony Music Entertainment, is releasing the DVD and Blu-ray version on Oct. 30, which will feature bonus content not included in the televised broadcast version.

The film documents the massive festival hailed then as the ‘Southern Woodstock’ and recognized now as the last great U.S. Rock Festival. The film presents the story of how rock music’s burgeoning festival culture descended en masse to the tiny rural village of Byron, Georgia and witnessed Hendrix’s unforgettable performance.

It document details the efforts by Atlanta promoter Alex Cooley to create the definitive music festival. Cooley secured such talent as Bob Seger, B.B. King and the Allman Brothers, but Hendrix was the critical component he needed to elevate the three day festival to a major cultural event.

Electric Church features interviews with Hendrix’s Experience band mates Billy Cox and the late Mitch Mitchell as well as Paul McCartney, Steve Winwood, Rich Robinson, Kirk Hammett, Derek Trucks, Susan Tedeschi, festival organizer Alex Cooley and many others.

The movie contains 16mm color footage of Jimi Hendrix’s Independence Day appearance, a mere ten weeks before his untimely physical passing.

Jimi Hendrix put the rock festival concept on the map with his blistering performance at Northern California’s Monterey International Pop Festival in 1967, headlining 1968’s inaugural Miami Pop Festival, and providing the soundtrack for the counterculture with a dazzling set at Woodstock in 1969.

Jimi’s performance at the Second Atlanta International Pop Festival was not only significant on a musical level, but also in terms of socio-political dynamics. The organizers were keen to push back against the cultural divide that was very much in evidence in the Deep South. It was assumed that rural audiences would not take kindly to “long-hair” bands, and that black and white artists could not comfortably exist on the same bill; Atlanta Pop set out to challenge those beliefs. Hendrix’s music and message of universal love made him the ideal artist to represent that pushback, and, appropriately, was the first act booked for the festival. By the time the Jimi Hendrix Experience took the stage on the evening of July 4, the audience swelled to more than 300,000.

Standout performances include such Hendrix classics as “Hey Joe,” “Voodoo Child (Slight Return),” “Purple Haze,” as well as confident, compelling versions of songs such as “Room Full Of Mirrors,” “Freedom,” and “Straight Ahead” that had not yet been issued by Jimi on an Experience album, but were intended to be part of the album he was working on that summer.

“The Star Spangled Banner,” played against a backdrop of exploding fireworks, is another highlight, which Cooley recalls as having “knocked peoples’ socks off.”

The Atlanta festival footage in Electric Church was shot by Steve Rash, later known for directing such Hollywood films as The Buddy Holly Story and Can’t Buy Me Love. Rash initially intended for the footage he and his team were filming to be used for a documentary in the vein of Woodstock. When a deal couldn’t be secured, virtually all of the film lay undeveloped inside Rash’s barn for over three decades. The full-color film stock held up remarkably well, and makes for a transcendent viewing experience.

Bill Mankin, who worked on the construction and stage crews for the festival, provides liner notes for the Freedom package, describing his first-hand account. He explains, “At the center of the vortex was the master magician on guitar: the personification of a life lived fully and wildly, with no boundaries, no limitations, and aiming for the stars at light speed.”

Sidebar

Dr. James Cushing: This brilliantly recorded Atlanta concert offers, among its other delights, a chance to hear clearly how deftly Billy Cox contributes to the music. Compare these versions of “Red House” and “Hear My Train A-Comin’” with those from the May 1968 Miami Pop Festival (also on Sony/Legacy) and you’ll hear how much more supportive a player Cox is. Redding sometimes sounds impatient with Hendrix’s tempos, but Cox, never.

“Billy Cox with Jimi Hendrix is a very different proposition than Noel Redding with Jimi Hendrix, mainly because Cox plays solidly on the beat where Redding tends to play ahead of it.

“For more evidence of how well Cox fits Jimi’s sense of time, study the low-fi audience bootlegs from the 1970 concerts (two of my favorites are Los Angeles 4/25 and Baltimore 6/13). The microphones in 1970 cassette tape recorders didn’t capture drums very well, so you’ll hear moments of virtual guitar/bass duet music here, and the two men seem to have worked out a perfect mutual understanding – unlike Hendrix and Redding.

“I wish there were more close ups of Cox in the Atlanta DVD – more of Cox and fewer interviews with Hendrix-loving celebrities – but that’s the only complaint. One watches Hendrix footage for three reasons.

“First, his hands (how is he creating this astonishing music?

“Second, his face (how does his expression connect with what he’s playing?

“Third, his body (what’s he going to do next?). There’s plenty of hands, face, and body in this well-lit, well-photographed doc, more than there is in Jimi Plays Berkeley. And when the fireworks go off during the Star-Spangled Banner, it’s a poignant moment; you can almost forget that there was a war on.

“Of the commercially released later Hendrix live recordings, the Berkeley, Atlanta, and Isle of Wight concerts have the best recorded sound, but the U.S. performances are stronger and more satisfying.”

End of Sidebar

Harvey Kubernik Interviews Billy Cox

HK: You met Jimi, then James Marshall Hendrix, in 1962.

BC: Yes. In Nashville in 1962. However we played in Clarksville, Mississippi. We went to Indianapolis and it was not very too good. We almost starved to death there but our girlfriends came and got us back to Clarksville. Then about six months later these guys from Nashville heard we were one of the best bands in Mississippi and wanted us to come and audition. But Jimi said OK. He told me personally, “we have to go to Detroit, Chicago or New York.”

“I took him into Nashville. 1962, ’63 and then early part of ’64 he was with me. All along he’d go off with some guy who promised him the world. An MC or singer. I’d have to send for him and bring him back to Nashville. He always had a place with my group. But he envisioned himself being successful. He activated the law of attraction back then. “When I make it.” “We’re gonna be good.’ “The world is gonna see some good stuff.” “We’re gonna make it.” And, eventually, he did.

“And one time he went off for six months. I look up and there is this bus and out jumps Little Richard and Jimi. Little Richard comes up to me. “You must be Billy Cox. Get your stuff and let’s go.” “Mister I can’t do that. I’ve got a group here. And my word is my bond. And if I were to leave with you I would have to give at least a week or two notice. I can’t jump up and go.”

“Little Richard thought I was crazy. At that time he was top dog in the entertainment industry. So they went off and I didn’t see Jimi anymore until he gave me a telephone call and told me this guy, Chas Chandler, had discovered him in New York and was going to make him a star. ‘I told him about you.” I replied, ‘I think you need to go yourself.’ I just gave him some little off the wall story. ‘Cause I knew at that time he probably would have made it with me. I’d be like an albatross. So however, he went on and did it. He called me to join later. He said, ‘When I make it I’ll send for you.’ And, that’s what he did.

HK: I have a theory about Jimi’s musical and performance art and this extends to you as well. Both you guys served in the military and jumped out of airplanes. Do you think that was a factor in playing a more bolder form of music? You had the combination of military discipline then coupled with airplane and helicopter-related duties. Perhaps it added to the theatrics I witnessed when I saw Jimi live.

BC: Yes. Commitment. And, on top of that, it built character. Above all.

HK: Even at Woodstock in August ’69, your bass playing kicks off “The Star Spangled Banner.” Am I reading too much about your joint military stint informing the musical journey of you and Jimi?

BC: No you’re not. You’re totally aware. Totally aware. We weren’t mocking the song at all. He was playing it. But everyone interpreted it the way they wanted to interpret it. That was up what he was against. Those who were positive: This is really great I hear the bombs dropping. They were positive. The others were: He should have not played that number there. That’s sacred. It all depended on what you got from the song. That’s all. Interpretation.

“Jimi knew he had something to offer to this world. He was a cosmic messenger and his music today is just timeless because right now I see all these young kids picking up guitars. If a periodical or magazine wants to see more copies than the previous month they put his picture on the front cover. So his music right now reaches down through generations. It transcends cultural boundries. Anywhere you go around the world there are young kids with guitars and playing them. I personally know 50 guys who just started off 40 some years ago and now they are into their sixties and they are Jimi Hendrix aficionados.

“Then with Jimi’s ability to write in the now. Like Beethoven, Mozart and Handl. That’s why the Experience Hendrix tours are concert events. The music of Hendrix performed by aficionados who just went into rooms, locked themselves up and got this stuff. A lot of them are on the tours with us. Jimi left one hell of a legacy.

HK: During your work and life with Jimi, did you actually have conversations about the power of music or the aspect of freedom in his life?

BC: There were conversations and he was working it out how he was really going to be able to implement this. But he himself, as a cosmic messenger, saw music as uplifting for all people. And I think that why his music is a timeless legacy. He wanted to bring people together. The Sky Church. The Electric Church. He also had a plan of the full manifestation of the Sky Church and Electric Church sound. But that was unfinished.

HK: I know a lot of people who list “The Band of Gypsys album as their favorite album. You dudes were on fire when those sets were recorded. The impact on funk, heavy metal, pop, rock and guitar playing. It was a product forced to be done from an earlier signed contractual demand on Jimi. I will admit I had to hear the full expanded complete sets on CD and vinyl reissue to fully comprehend what went down at those sets. You smoked.

BC: People talk to me all the time about that. A lot of time I’m in the lobby or hanging around the merchandise tables and people just grab and hug. One couple came up to me and offered me ten acres of land just so I could live in the same state down the street from their home!

“The Band of Gypsys turned the world upside down. Jimi was at his peak then. He had done [earlier] albums and then I came on board with a lot of the things we had. He called them ‘patterns,’ but they’re just riffs. We played around with them and a lot of times he’d say, ‘If people heard us play this stuff they’d lock us up.’ But we were completely free musically.

“So the Band of Gypsys Jimi was at his peak. Buddy Miles! Oh man! What a guy. No restraint. The Band of Gypsys was a trend-setting group. We didn’t know that. But it has been said that the Band of Gypsys inspired reggae, free-form rock, portions of rap. Jimi wrote about 90 percent of that stuff. And Buddy had Them Changes. We did some stuff that we put together that we enjoyed which had a rhythm feel to it.

HK: When you recorded the shows that night did you know that you were spot on?

BC: We were on big time. After the first set when we walked off, I remember Jimi telling me and Buddy, he was smiling, “It’s gonna be all right now.” (laughs).

HK: Can you discuss playing bass with Jimi’s drummers, Mitch Mitchell and Buddy Miles? Any distinct differences in the way you interacted with each of them in the Hendrix sound. Live and on record.

BC: I liked playing with Mitch. I came from a jazz influence in being from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. A jazz hub. Like Philadelphia and New York. My uncles played horn. I was at home playing with Mitch. Equally at home playing with Buddy who was R&B-oriented. Jimi picked probably two of the greatest drummers he ever could have had.

HK: How did you like playing bass with someone who helped introduce the wah-wah pedal to listeners?

BC: I liked it. We’d go to Manny’s Music store in New York. We’d try out the gadgets. “Hey. Let’s try that one. It’s pretty good.” I was positive about all of that and enjoyed it. I think the more gadgets the better. I liked playing the songs with a new twist. As far as equipment and amps, whatever the roadies had. Mostly Marshall amps. Then Acoustic. I wasn’t picky. Let’s get a good sound. As long as it’s got mids, highs and lows I’m a happy camper.

HK: You played a lot of music festivals with Jimi.

BC: At Woodstock I had never played to as many people. In a way it was frightening. But you know, Jimi had this uniqueness about him. His thought patterns were unique. In the way he spoke. Mitch and I looked out at the audience. Jimi looked out and with all his knowledge and his wisdom, “You know what? Those people are sending an awful lot of energy up to the bandstand. What we will do is take that energy and utilize it and send it right back to them.” With that in mind we stayed up on that stage for almost two hours.

“That’s how the Isle of Wight was done and the Atlanta Pop Festival. Same thing. By this time we’re getting used to these crowds.

HK: Guys like you and Jimi in the very early sixties had gigged in the Southern United States and seen and witnessed racism and some aspect of Jim Crow Law divided audiences. Here you are in 1970, in Atlanta, and it’s very integrated and you’re a top billed headlining act. I suspect it is not lost on you that three, four or five years earlier you would be hassled even going to a show. I know most of the crowd in Atlanta were white people, but there seems to be a real sense of community.

BC: You know, it really didn’t have anything to do with race. It was being linked together cosmically, I guess. I was in Jimi’s head. He started off “All Along The Watch Tower” in the wrong key. I started off in the wrong key with him. Because wherever he went I was right on him. Then Jimi got on the microphone and went to the original key and I was on him right then and there. When we got off the stage he said, ”You were right on me like white on rice.” “No. I was right on you like a rat on cheese.” And we laughed at that. We were cosmically linked musically. Because we rehearsed, practiced at hotels, making mistakes and learning. We went to recording sessions early so we could get some rehearsal time so we could do some new riffs. And that’s the type of relationship we had. Me and Jimi covered a lot of ground together. We had traveled many miles together. He was like a brother. And it was sad to lose one of my brothers.

HK: What is it like for you to hear Jimi’s music or see yourself playing with Jimi on film?

BC: It’s sad. It’s happy. But I look at it more so like with this new Freedom: Atlanta Pop. We did “Freedom,” “Straight Ahead,” “Message of Love,” “Room Full of Mirrors.” These are songs the audience never heard. And when we got off the stage from that show, Jimi said, “You know. We must be pretty good because they never heard “Freedom,” “Straight Ahead,” “Message Of Love,” and “Room Full of Mirrors.” And they really went crazy. So we must be riding in the right direction.” We laughed. People enjoyed the songs, more so than the old songs. Like “Foxy Lady” and “Purple Haze.”

“When I see or hear Jimi’s music it’s magic that happens. It’s the original and the feeling. A lot of time he was bombarded by financial, attorneys, and management. Why does a creative individual have to go through all that bull crap? A lot of times you could see it on his face. “What’s wrong with him?” “Well he’s worried about this goin’ through his mind. Sued.”

“Now today they protect the artists a little more so now against all of that bull crap. And they are free to do what they are supposed to do. Play and create. And be a part of what they are. Instead of being worried. A lot of times you saw Jimi worried. But those days when he was not worried we cracked enough jokes and got away from all that bull crap, he was jumping down and playing behind his back and he’s putting on a visual show. The sound is great. That’s what happens in a situation where Jimi Hendrix wasn’t involved in too much of the business.

“Jimi was bombarded with a lot of crap that was unnecessary for a man who is supposed to be about the music. However, all and all, there were moments when he was the same guy. But Jimi became more and more a spiritual person. He knew that spiritual multiples. It never divides. So his music just brings people together. The most important thing was his spirituality and bringing people together. And he was very serious about the music and the music was all he ever thought about more than anything.

HK: Did you guys ever discuss concert repertoire? Set lists?

BC: Never had a set list. Jimi always starts the song off. He was the boss. So wherever he wanted to go that’s where we went. Normally from “Foxy Lady” to “Voodoo Child,” to “Freedom” and “Straight Ahead,” Jimi starts it first and we know where he is gonna go and where he went. We practiced so long and we knew all the keys. So if Jimi wanted to extend it, he would look back, we knew what that cue was. Maybe he would raise his hands to the left or to the right. We knew the cue. He was the boss and we knew where he wanted to go.

“Janie Hendrix has done an excellent job protecting his music. Her team around her are doing a great job. The Experience Hendrix Tours have been very successful. That shows there’s a need for that and people are enjoying. Jimi’s music is timeless. The stuff we heard back in the sixties and the seventies still sounds fresh and unique now. They’ve gone into the vault and brought out some great stuff. I hope they continue keeping their energy up and doing the same thing they are doing. I’m a happy camper.

(Harvey Kubernik has been a music journalist for over 42 years and is the author of 8 books. During 2014, Harvey’s Kubernik’s Turn Up the Radio! Rock, Pop, and Roll in Los Angeles 1956–1972 was published by Santa Monica Press.

In September 2014, Palazzo Editions packaged Leonard Cohen: Everybody Knows, a coffee—table—size volume written by Kubernik, currently published in six foreign languages. BackBeat/Hal Leonard Books in the United States.

Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik wrote the text for photographer Guy Webster’s first book for Insight Editions published in November 2014. Big Shots: Rock Legends & Hollywood Icons: Through the Lens of Guy Webster. Introduction by Brian Wilson).

In November, Back/Beat/Hal Leonard will publish Harvey’s book on Neil Young, Heart of Gold).