January 19, 1943 Port Arthur, Texas–October 4, 1970, Hollywood, California

By Harvey Kubernik © 2020

50 years ago on October 4. 1970 at the Landmark Hotel in Hollywood the performer and singer Janis Joplin died of a heroin overdose.

Singer/songwriter, producer and guitarist Bobby Womack was one of the last two people to see Janis Joplin alive after she went to the restaurant and bar Barney’s Beanery in West Hollywood following a recording session with Paul A. Rothchild at Sunset Sound.

“Paul Rothchild lived in Laurel Canyon. He did The Doors and Pearl, the last Janis Joplin album,” Bobby Womack told me in a 2008 interview.

“I loved Paul. Rothchild was at the studio and he said, ‘Man, she loves you. You guys should hang out. She’ll be good.’

“All I know is that Janis Joplin called me. I didn’t know how she got my number. ‘This is Janis.’ ‘What are you calling about?’ I didn’t think it was her. ‘Well, everybody else has recorded your songs and I just want to do one of your songs.’

“She was a person who joked all the time. ‘Why don’t you come to the studio? It’s on Sunset. Come to the studio and bring me some songs.’

“So I brought her every song I had ever written that were recorded and not recorded. And she said, ‘when I push the button that means I like it. If I don’t push the button then you gotta quit and go to another song.’ Janis did my tune ‘Trust Me.’

“So as soon as I hit the first song ‘Trust Me,’ she pushed the button. ‘Shit, this is gonna be easy. I’m gonna have the whole album’ I said to myself. She never pushed the button again…I kept on singing and ran out of songs. And Janis said, ‘Don’t you get it? The first song you gave me I loved it. That’s it. Let’s cut it.’ And I played on it.

“In a little short time we became very close. I remember her coming to the studio the next day and she was very upset because she was sayin’ ‘Jimi Hendrix passed.’ She was very upset. ‘Oh baby, I know you feel bad…’ And, I shared my own experiences about meeting him.

“The first time I saw and met Jimi Hendrix to really know him when he was with a guy named Gorgeous George, who was a guy who made clothes and always thought he could be a Sam Cooke or Jackie Wilson. It was on a show when I was playing guitar for Sam, on a bill with Jackie Wilson and James Brown.

“She then joked about ‘Oh, I plan to kill my own self. Now with Jimi just leaving I ain’t gonna get no publicity.’ She was joking like that all the time.

“She liked my car. [“Mercedes Benz,” written by Joplin with Michael McClure and Bob Neuwirth, was recorded for Joplin’s Pearl sessions after she took a ride in Womack’s vehicle].

“Later, Janis said to come by the Hollywood Landmark Hotel. I go to the hotel and we were partying…

“She was very respectful. I found out a lot about her in a short time. The thing that blew me away about Janis was when she asked ‘what bothers you the most in this business as far as the black and white thing?’ And I told her, ‘every time I cut a record I try and cut a record so I can cross over to appeal. I just don’t cut the record. I just want to be able to cut a record and that’s it.’

“And I said, ‘What about you?’ ‘Everybody keeps saying I’m trying to be Tina Turner.’ That blew me away. ‘You don’t sound nothin’ like her.’ And jokingly I added, ‘You don’t look anything like Tina. Well, we both got this problem. So why don’t we do something together like a tour? You go out there and let them know.’

“I hadn’t heard this Tina thing and told her it was in her head. She was very serious. Janis loved Tina Turner.

“It’s very hard to put the racial thing in the mix with musicians. It’s deeper than that. It never fazed them. See, everybody looked out for everybody. So that never came up but only to the outside people. And that’s just the way it was. We would joke about it and talk openly about it. Anything.

“And she ran down how she went to high school and blew the school that used to think she was ugly. And she was talking about the problems she had.

“Janis was into brown, [heroin] which I don’t do, and I was into cocaine. The phone rang and she told me to go. Someone was coming to visit her. As I went into the elevator I remember hearing a guy [alleged heroin dealer] coming up the stairs.

“Paul Rothchild then called me early that morning, and he says ‘she OD’d.’ And I said, ‘You got to be joking me…’

“That just broke my heart. Broke my heart…

“In talking about that was something I could never adjust too. Is seeing somebody today and losing them tomorrow.

“Damn, I keep losing people I love and didn’t know I loved them this much until they aren’t around. Maybe it’s the thing where we become messengers for some people who aren’t here. But boy, sometimes I’m telling you I need some help with these messages. Sometimes they go too fast,” sighed Bobby.

“I lived right near the Hollywood Landmark Hotel where Janis died in October 1970,” recalled filmmaker [Imagine: John Lennon, This Is Elvis] Andrew Solt of SOFA Entertainment.

“On that day I was driving to my job at KTLA-TV on Sunset Blvd. and went by the Landmark on Franklin Ave. and noticed the EMT ambulance in front just as the news was all over the radio stations.

“I had seen Big Brother & the Holding Company a few times in 1967 in San Francisco at the Avalon. They were a really good band. I was at the Monterey International Pop Festival in ’67 and familiar with the group when they came on stage. Janis was dynamite. I had never seen a white woman sing like this!

“I later saw the group in Venice at The Cheetah in early ’68. Around the same time I went to the Whisky A Go Go one night, might have been for Big Mama Thornton. Janis was standing there alone with the crowd. I said hello. I loved the Cheap Thrills LP.”

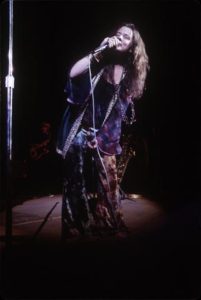

I witnessed Janis Joplin on Friday June 20, 1969 at a rock festival, Newport ‘69 at Devonshire Downs in Northridge, California. The Jimi Hendrix Experience, the Don Ellis Orchestra, Albert King, the Ike & Tina Turner Revue, Spirit, the Edwin Hawkins Singers, Joe Cocker, Taj Mahal and Southwind were booked.

Free spirit Joplin was a special invited stage guest.

Janis greeted the adoring crowd with an energetic directive “Keep on rockin’ people!” She was met with an ovation from the throng savoring their collective moment in the San Fernando Valley.

Janis Joplin possessed “the tools of conquest,” as narrator Rod Serling summarized in an epilogue about a character of his television series, The Twilight Zone.

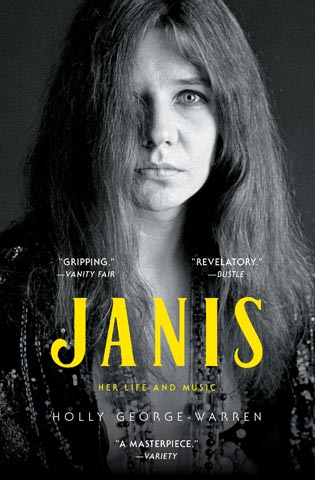

In October 2019, Simon & Schuster published Janis: Her Life and Music by award-winning author Holly George-Warren. A paperback edition is scheduled in 2020 for October 13th.

Roseanne Cash hailed George-Warren’s literary achievement. “I’ve been waiting for the right person to write the definitive biography of Janis Joplin! All fans should be grateful it’s finally here. Janis lives and breathes freedom and soul, and Holly George-Warren captures that spirit perfectly.”

“Janis Joplin was not a victim,” Holly emailed me in August 2020.

“She was a cultural outlaw who knew the risks of the chances she took. A hardworking musician, she strove to be the best singer in rock & roll. Early on, she immersed herself in artists like Bessie Smith, Lead Belly, Big Mama Thornton, and Otis Redding, and she gradually created her own sound. An ambitious and restless artist, Janis transitioned from solo acoustic blues singer, to blues-rock screamer in Big Brother and the Holding Company, to R&B/soul shouter backed by her Kozmic Blues Band, to forerunner of what is now called Americana music, leading her Full Tilt Boogie Band and recording her swan song, Pearl.

“Touring the country when my Janis: Her Life and Music was published, I was delighted to see thousands of Janis fans, for whom her music is a vital part of their lives. What great stories I heard from some who met or knew her, others who saw her perform, and from many more who discovered her music long after her death. As Melissa Etheridge said from the stage when Janis was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1995, “When a soul can look on the world, and see and feel the pain and loneliness, and can reach deep down inside, and find a voice to sing of it, a soul can heal.” We need Janis’ music today more than ever.”

During January 2019, the Broadway bio-musical, A Night With Janis Joplin, which ran in the 2013-2014 season, featuring the original production starring Mary Bridget Davies, was available on theatrical streaming platforms. Davies garnered a Best Actress nomination in a Musical Tony Award for her role of Joplin.

The Broadway HD multi-camera shoot was done in October 2018 at the La Mirada Theatre for the Performing Arts in Los Angeles when the production was touring.

A Night With Janis Joplin is written and directed by Randy Johnson with musical direction by Brent Crayon and choreography by Patricia Wilcox. The event was produced by La Mirada Theatre for The Performing Arts and McCoy Rigby Entertainment in association with T&D Productions, LLC.

After the 1974 Howard Alk-directed Canadian documentary Janis, 1997’s E: True Hollywood Story Janis Joplin, was a 2016 American Masters premiere of director Amy J. Berg’s documentary Janis: Little Girl Blue, and the DVD and blu-Ray from FilmRise followed.

2017 was the 50th anniversary edition of director D.A Pennebaker’s Monterey Pop that captured Joplin’s 1967 star turn and a 2018 REELZ Channel television series Autopsy: The Last Hours Of…Janis Joplin. There was also a 2017 cancelled biopic Get It While You Can to star actress Amy Adams.

Currently in discussions is Love, Janis, authorized with the Joplin family, based on the 1992 intimate biography by the singer’s sister, Laura Joplin, which might be headed to a feature-length movie destination with actress Michelle Williams, who in 2016 signed on to the project.

During this century I’ve talked to Janis Joplin’s fellow musicians, friends, music business associates, photographers, artists, deejays, writers and fans about her endearing and enduring legacy.

Marty Balin: I grew up and got to see all the jazz cats in the clubs. Plus, I saw all the beatniks, and great writers and poets. This is a world before 1967 and the Summer of Love. It started with the beatniks and poets.

“I think San Francisco was full of all these people who were talented and who were expressing themselves or their rights or playing music. And I think San Francisco has a lot to do with that. I don’t know if it’s the geomagnetic forces of the earth and the ocean but something went on there. It’s a lot different than the rest of the world.

“In 1965 I helped open the Matrix Club and did some booking in 1966 and ’67. People were comin’ in lookin’ for places to play, the infamous Warlocks and Janis. I had an immediate influx of people. And besides that, I had jazz guys playing there. Blues guys, and cats from The Committee.

“Grace Slick was real popular at the time with her own band, the Great Society. She had her brother and her husband in that band. When we need to get a new girl, because Signe [Anderson] was pregnant and she didn’t want to tour outside San Francisco, so we needed the new girl.

“There were only three girls around singing: Janis in Big Brother, Grace with the Great Society and Lydia Pense, later of Cold Blood. Janis.

“I have heard people sing ‘Summertime’ by the thousands. I have never heard anybody do ‘Summertime’ like Janis. She sent chills up my spine and I’m standing on stage watching her do it. It was just amazing. I thought she was a great entertainer and just a fun person. People loved her.”

Kim Fowley: I was almost in Big Brother & the Holding Company. The band heard my record ‘The Trip,’ and thought I had the goods. But I wasn’t interested in living in San Francisco, which was damp and foggy.

“Chet Helms had brought Janis up from Venice, and she auditioned and got the job. She was tremendous. Janis was a chameleon who was a homely girl off stage but a goddess and a sensual animal on stage as soon as she opened her mouth and started prowling the stage. It was that beauty from within thing that made it happen for her. She spent a lot of time listening to Odetta, Etta James, Bessie Smith and Big Mama Thornton.”

In 1966 Janis Joplin was the lead singer in Big Brother & the Holding Company who were generating attention around San Francisco.

“The San Francisco scene was charming but chaotic,” remarked Elektra Records founder and the visionary talent scout Jac Holzman to me in a 2017 interview.

“No one seemed serious and I didn’t get that this was the reason people loved the place. I was not at the center; I felt like a voyeur.

“LA was where I finally found what I was looking for. The time was the summer of 1966, and the place was the Sunset Strip, which had suddenly morphed before everyone’s astonished eyes into the hippie navel of the universe.

“In San Francisco, Paul Rothchild and I tried to recruit Janis Joplin for Elektra. In 1966, she brought her guitar and sang for us at a mutual friend’s apartment-incredible power, the room was too small to hold her. She just about pushed you against the wall. Paul and I knew she deserved a better backing band, but Janis insisted on sticking with Big Brother and the Holding Company, and she was equally reluctant to let us talk to her record label about buying out her contract.”

In summer 1967, a year after recruiting Joplin, they released their self-titled debut album Big Brother & the Holding Company on Mainstream Records, produced by Bob Shad, culled from studio dates in Chicago and Los Angeles. “Down on Me,” “Blindman,” and “Bye Bye Baby” showcase some of Joplin’s purest vocals ever waxed. The outfit continued to build a devoted fan base in their native San Francisco and around the Bay Area.

Their performance at the Monterey International Pop Festival in June 1967 earned Big Brother national recognition, with Joplin’s unrestrained full-tilt delivery bringing audiences to their feet. Clive Davis, president of CBS Records was in attendance, who signed Big Brother & the Holding Company to Columbia Records.

On September 15, 1967, Bill Graham presented The San Francisco Scene at the Hollywood Bowl with Jefferson Airplane, Grateful Dead, and Big Brother & the Holding Company.

“I scored tickets to my favorite SF band, Jefferson Airplane, and the Grateful Dead and to see Big Brother play live but was disappointed when they were a no show,” confessed writer Marina Muhlfriedel.

“Still, the night remains vivid. Grace Slick invited the audience to come on stage and a cousin and I hopped to it, dancing around Jorma Kaukonen through the final encore of the show.

“I was a latecomer to Janis Joplin. My big sister ran away to Haight Ashbury in early ‘66 and in the months that followed, she turned me on to Big Brother and the Holding Company and so many other bands.

“Of the pack, Janis and Big Brother were the least relatable to 13-year-old me. There was something feral about Janis. She was so full of wild woe and yearning. As a fledgling peace-and-love flower child, sheltered by my West LA upbringing, it was difficult to connect to her yanked-from-the-bottom-of-one’s-soul angst, that bluesy tough Texas stuff.

“A few years later, in high school, I kind of fell in love with the blues and particularly Bessie Smith, and that thread led back to Janis. By then, her crying heart grabbed mine as she wailed life’s true blues.”

Paul Kantner: Janis did it every night I saw her. She used to play in clubs around town. Grace with Jefferson Airplane and Janis were at Monterey.

“Probably the reason that Janis died was that she got too popular and left her band. To her credit, Grace didn’t leave the band and probably survived as a result.

“There’s a big difference between the two. Grace got, as you can imagine, all sorts of offers to go solo. On one level she didn’t feel confident enough I know a little bit. On another level she didn’t want to leave the band the way it was.”

Grace Slick: Most singers had a band, but to be able to front that volume of music, you can’t just kinda stand there (laughs). For rock ‘n’ roll – these people are not opera singers, O.K.? It’s not the business of how fine and pristine your voice is. It’s about the entertainer enjoying himself not the audience. Hopefully the audience will. If the entertainer is enjoying himself and feels at home on a stage, that’s 50 percent of it. The audience and the bands were not that separate. In other words a large amount of the audience was the other bands at the time. There were lots of bands that were working in San Francisco and we played with each other on the stage sometimes.

“As a rock ‘n’ roll force I mostly liked Bill Graham and his energy, both physical and mental. He was able to keep an awful lot of balls in the air. He could organize, and do business, whereas most of us were on the artistic side, which is a positive thing, but we would not have been able to deal effectively, I don’t think, with the business end of it, which he did. And without that, we would not have had what we did, a venue to express ourselves.”

Bill Graham: In the long run it’s the public that has to get the good energy from them. I really sincerely feel this, is that the reason the relationship lasted over the years, is that those of us who live in the Bay area and lasted over the years have always had the same goal. We want to turn people on and we want them to have a good time.

“There is something that the Grateful Dead always had in common from the beginning, something hardly spoken about in the media after all these years.

“The San Francisco bands, starting with the Dead, always went to the gigs with the intention of putting it out there. It was the lack of professionalism at the beginning that made that possible. It wasn’t that the contract said 45 minutes and ‘that’s what we’ve got to play.’

“They were the first one who asked to play longer. They wanted to extend the relationship between the audience and themselves.”

In a 1976 interview I conducted with Jerry Garcia inside Bill Graham’s Mill Valley residence for Melody Maker, Jerry discussed the 1964-1976 sounds emanating from San Francisco.

“One of the things you could say about all the bands that came from San Francisco at that period of time was that none of them were very much alike. I think that the world has changed. I think the United States has changed very visibly in the last ten years. A lot of it had to do with what happened in San Francisco.

“I can’t say how or why, but I also think it’s affected everything. Just all the interest in things like ecology. All the interest in the sense of personal freedom as expressed by all kinds of movements. All these things were designed to free the human. Social overtones. All that stuff. The communal spirit. I really think the scene out here created the possibility for Woodstock to happen. The Monterey International Pop Festival. The thing, the activity, music and people. The set-up was out here.”

The 1966-67 California psychedelic blues and soul world of Janis Joplin was still very much inspired by the pervasive influence of the San Francisco, Berkeley and Venice beat generation literature and poetry she first discovered with fellow Bohemians in Port Arthur, Texas at Thomas Jefferson High School and the University of Texas in Austin. Three of her favorite writers were Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg and Michael McClure.

Allen Ginsberg: I thought the whole 40’s, 50’s literary movement was historically really important, and was kind of a wall built against authoritarianism, that there would be a counter reaction and maybe a police state in America someday, building on the drug thing, and the suppression of literature.

“People are now more receptive to candor, cheerfulness and some kind of openness and reality against the pessimistic, negative FBI in the closet, J. Edgar Hoover secrecy then, when we were proposing a better world.

“In fact, I remember when Kerouac was asked on The William F. Buckley TV Show in the 60’s. ‘What Beat Generation meant?’ Kerouac said, ‘Sympathetic.’”

Ram Dass: Back in the 60’s and early 70’s, I spent a lot of time at The Fillmore, The Avalon and Family Dog in the San Francisco area. I went to The Monterey International Pop Festival and it was a time when the San Francisco sound was rock by Jefferson Airplane, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Big Brother and the Holding Company, Grateful Dead.

“What I loved was that these experiences were community and a ritual of a very high order. Where people felt safe to be open and very uninhibited and there was a sweetness about it all.

“We’re on a journey together, and I’ll be as honest as I can about my trip and you can do whatever you want to do, but I’m going to create the space where it’s safe to be very vulnerable. That’s about drugs, sexuality, about politics, everything.”

Playboy Magazine’s reporting on the contemporary music scene of 1967 spread the June Monterey Pop happening and the counterculture revolution to a much wider audience. The Jazz & Pop Poll ballot of October 1967 reflected the current audio climate.

In the Male Vocalist category, Marty Balin, Jimi Hendrix, Otis Redding, John Mayall, Scott McKenzie, and Johnny Rivers were now listed with Frank Sinatra, Gene Pitney, Sammy Davis Jr., Al Martino, and Mose Allison.

The Female Vocalist listing now found Janis Joplin, Cass Elliot, and Grace Slick right alongside Dionne Warwick, Julie London, Anita O’Day, Jackie DeShannon, and Eartha Kitt.

Sam Andrew: Monterey was a watershed event for Big Brother and the Holding

Company and, indeed, for the entire San Francisco counterculture.

We had a clear idea about what was going to happen there, when we signed up for the Festival.

‘“Combination of the Two’ was a song that I had written a while before this. The ‘Two’ were Chet Helms and Bill Graham. In the song I was trying to make the point that the scene needed a visionary and also someone who could make the trains run on time. It would take a combination of the two to make the counterculture work.

“Of course, as often happens, in the actual playing of the song a sort of rapturous ecstasy took over and the lyrics became almost totally lost. I tried to describe what it felt like to be at the Avalon Ballroom or the Fillmore Auditorium. So, the song which had begun as an almost philosophical observation (the complexity of describing an experience) became, in performance, a raving chaos. Janis Joplin lifted the chorus of the song into the level of pure feeling.

“Of course the big story for us was the introduction of Janis to the big world and that went well enough. People who had never heard/seen her understood suddenly what she was about.

“I liked playing ‘Road Block’ at Monterey. There is a kind of gospel, off time feel to the song that I found very interesting.

“Everything changed for the scene at large and for Big Brother in particular at Monterey. We acquired Albert Grossman as manager, Columbia Records for a recording company, and we began to live in New York and Los Angeles at this point. There was a big shifting of gears. We were off into our new life and Monterey marked the beginning of that.

“At Monterey we heard a door opening into a whole new world. What had until that time seemed to be a very small scene of people trying to find a way to a new and more just life was now shown to be an international movement. Monterey was where literary San Francisco met hedonistic Los Angeles and both sides won.

“The theme was the combining of so many seeming opposites, north and south, east and west, black and white…for me the most enlightening performances there were those of Jimi Hendrix and Otis Redding…man and woman, vision and reality, straight world and counterculture. Monterey was the place where these extremes melded together for one magic moment.

“Big Brother rehearsed for a week before we played the Festival. For some reason, we knew that Monterey was going to be a signal event, one that we would remember for a long time. Commercial considerations, networking, career moves, things that seem of paramount importance today, were almost beside the point at this time. There was a messianic feeling that all of us, musicians, photographers, artists, filmmakers, were in this together and that our togetherness was going to solve effortlessly many of the problems that had plagued human beings for an eternity. What can I say? It was the 60s, but we actually believed for a brief, shining moment that we could make a difference.”

Tom Gundelfinger O’Neill: I had already been to the Fillmore auditorium and seen the Grateful Dead. They were not boring. I had seen Jefferson Airplane and Janis Joplin and Big Brother and the Holding Company.

“In 1966 I had a one on one with Janis. She was wearing black slacks and a white blouse. She and her group played in a conference room with a low ceiling, part of the Monterey fairgrounds. I was restricted from taking photos but awe struck by the music.”

Dennis Loren: I arrived in San Francisco in the spring of 1967, I felt like I had ‘died and gone to heaven.’ I usually went to The Matrix on Thursday night, The Avalon Ballroom on Friday and The Fillmore Auditorium on Saturday.

“I frequently went to The Jazz Workshop, Coffee & Confusion (where, according to Chet Helms, Janis Joplin got her first gig) and The Coffee Gallery. They were all located in in North Beach, and The Blue Unicorn Coffeehouse near the Haight-Ashbury district.”

Carol Schofield. I listened to Cheap Thrills quite a bit as well the first LP. I saw Janis and Big Brother many times at the Fillmore. And the show I have a vivid memory of was the Avalon, when she belted out ‘Down On Me,’ she tore the crowd up with that.”

Robert Marchese: I had gone to San Francisco with Johnny Rivers and Jimmy Webb to scout talent. Johnny Had Soul City Records. We went to see Big Brother and The Holding Company with Janis Joplin. And we went to the Fillmore, and afterwards, I said to Janis in a very subtle way, ‘you’re gonna be at Monterey?’ And I winked at her and she cracked up. “And I had met Albert Grossman a couple of times and liked him. I saw Janis before and after her Monterey set. She came up to me and I told her ‘to wait until Albert saw her.’ I said to him, ‘well, what do you think? Ten million?’ Albert just busted up. He was standing there with that shit-eatin’ grin. “I liked her and loved the band. I liked Sam, and I loved Jim Gurley, I thought Gurley at the time was the greatest one note psychedelic guitar player. I thought as long as she was with them she would survive.”

Ravi Shankar: Janis Joplin at Monterey. I had heard of her, but there was something so gutsy about her. Like some of those fantastic jazz ladies like Billie Holliday, that sort of feeling. So I was very impressed by her.”

Henry Franklin: I was with Hugh Masekela and we arrived the day of the Monterey festival. It was wonderful. Hugh was a great bandleader and nothing but fun. We stayed for the whole festival. I got to see Jimi Hendrix, Otis Redding, and I saw a little bit of Janis Joplin. She was nothing but energy. I learned a lot about her later in life. The feeling of the whole place was that everyone loved everyone. I was amazed. The world was different then.”

Henry Diltz: Janis was just totally on fire and sang with every ounce of emotion she had. I’d never seen intensity on a stage before. I also saw her in 1969 at Woodstock and the Hollywood Bowl on my birthday. It never occurred to me back in the ‘60s and ‘70s when I was really shooting all these things that it would ever be an archive and that it would be a piece of social history. That’s what it has turned out to be. And that was a total accident. The thought never occurred to me.”

Keith Altham: Janis was the staggering thing I saw on the whole show to me. Because I had never heard a woman sing like that. I told her afterwards, ‘You’re the best female rock singer I’ve ever heard in my life.’ She looked me up and down, smiled, and said, ‘You get out much, honey?’ I thought it was funny. She was very friendly. I liked her.”

Jim Yester: I felt the festival was a big step in healing the riff between the LA and San Francisco bands and it was very cool. I thought it was a great unification thing for all the California groups. I certainly felt no angst from any of the San Francisco bands. I think it had been going on when we [The Association] went up there in 1965, ’66, with the Beach Boys at the Long Shore Man’s Hall, and kind of got a cold shoulder. As far as the Monterey International Pop Festival, that was history. Listen, we were ‘heads’ like everybody else and just as crazy as everybody else, but we took care of business. We stayed at the same motel as some of the bands, and right next door was Pearly. (Janis Joplin). We met her. I was blown away. She was very down to earth, played with all the kids.”

Richie Furay: At Monterey Otis Redding captivated the audience. Hendrix had charisma. Johnny Rivers, I’m telling you man, the guy is a talented guy. Janis Joplin she was a powerhouse at that show. I was taken back by Jimi Hendrix and the Who. What are these guys doing breaking their guitars, man? It cost me a mint to get my little guitar.

Clive Davis: At Monterey I was really just getting my feet wet. I was in the business side of it for a year. I was working with Andy Williams, the young Barbra Streisand and Bob Dylan, and signed Donovan to Epic in 1966. I was observing.

“I was seeing the business change. I was seeing music change, but I was waiting for the A&R staff to lead into these changes that were showing evidence in becoming important in music.

“In June I really came to the Monterey International Pop Festival not knowing what to expect, but seeing a revolution before my eyes. I was very aware that contemporary music was changing.

“When Janis took the stage at Monterey, it was an unknown group to me totally, Big Brother & The Holding Company, and right from the outset it was something you could never forget.

“She took the stage, dominated, and was absolutely breathtaking, hypnotic, compelling and soul shaking. You saw someone who was not only the goods but was doing something that no one else was doing. With that fervor, that intensity, and impact,

“So, that in effect, coupled with everything around me, the way people were dressing, what was going on in Haight Ashbury, the spirit in the air, and the feeling. I just said, ‘You know, I am here at a very unique time. I’m feeling it. I’m feeling it in my spine. I’m feeling it in my sense of excitement. I’m feeling it in the impact. It’s not only musical changes, but in society changes. And I, in effect said, ‘this is really, although it sounds hokey or cliche, this is the time that must mean that I’m gonna have to make my move.’

“There’s no question that the primary signing was Big Brother and Janis Joplin, but the Electric Flag was very powerful with Buddy Miles on drums, and Mike Bloomfield on guitar. I quietly signed the Electric Flag. Laura Nyro was not great at Monterey and I didn’t come away with the feeling I must sign here then.

“The whole experience if one asks, you know, and catalogs, or thinks back on the most meaningful experiences in your life, it would rank up there at the top. The impact for me afterward was that I realized that I was in on something unique, possibly revolutionary early.

“So I quietly, obviously, had to negotiate The Big Brother contract out of Mainstream Records. It wasn’t that (Albert) Grossman was their manager at the beginning, he was not, he ultimately came in as manager, and it was after he came in that we came up with a solution of buying the contract.

“Monterey was very different and unique. It’s not that I went around following festivals…Festivals grew up successfully around the artists that had either broken or were breaking. Monterey was the discovery of new talent.

“The success of the artists I signed at Monterey gave me confidence that I had good ears. It was there’s no question I was going to get confidence from nothing else. I mean, basically, that was a move I had made, and the fact that they came through in a resounding way, and were critically welcomed as well as commercially they reverberated.

“I had no idea I had ears. I had no idea that I could do this. It never occurred to me that I would be doing it, and so that as each step came through it emboldened me and gave me the confidence to trust my own instincts. And, that’s the only way that I’ve ever done it. Because obviously, up until that time, my background was totally different and it was a talent that I never knew I had. This was something that I not only loved doing but I had a talent for.

“Monterey is a without question, probably the most vivid memory from a career point of view, from an emotional point of view, from a character effecting point of view, that I’ve ever had.” Johnny Rivers: At Monterey I saw Clive Davis jump out of his seat. I was standing in the wings of the stage, and after that, man, he was on Janis like a cheap suit.

“When you got down to it, the highlights were the acts that were still playing the blues, Otis Redding, Janis Joplin and Big Brother. I loved Lou Rawls.

“After the Monterey Pop Festival everyone ran to San Francisco after that. It was almost too late. I mean, there were a lot of interesting groups coming out of there like Quicksilver Messenger Service. I had scouted Big Brother & The Holding Company before the event. Nik Venet, who produced my first album, was at Capitol Records and had something to do with Quicksilver signing to the label.”

Paul Body Big Brother and the Holding Company, we were not prepared for what went down at Monterey. Janis Joplin was braless, chunky, moon faced and she was like nothing ever seen by this San Gabriel cool cat.

“See, for soul singing we were used to gowns, girdles and perfect wig hats. Janis was none of that. She wasn’t a great singer but she got her point across. She wasn’t even wearing high heel sneakers, her shoes were silver.

“I got so blown away that Al Kooper played after her and I can’t remember if he did one of my favorite songs at the time ‘I Can’t Keep From Crying Sometimes.’ I was sort of in a daze until the Electric Flag came on.”

Al Kooper: I saw Big Brother & the Holding Company at Monterey. I didn’t care for Big Brother but thought Janis was amazing, as a stage performer and a singer. Very unique. And she stole the show and then they put her on again. She played one night and she killed them so bad they put her on the next afternoon so she could be filmed by D.A. Pennebaker.”

Joel Selvin: The thing was the backstage drama: Janis versus the rest of the band. It came as a big surprise to everybody. They had been living in this hunting lodge in the wilds of Marin as a commune. The girls sat around and strung glass beads. It was a very all-for-one-and-one-for-all thing. Nobody had any idea that Janis wanted to be a star. And I don’t know if Janis did, until after that first performance. You know, she wasn’t in the center of the stage with Big Brother. Grossman undermined that whole Janis thing. He talked to her backstage. At first Janis and the band did not want to be filmed.”

Lou Adler: The cameras had to be shut down for Janis, that wasn’t just Albert but [manager] Julius Karpen, before Grossman took over. Actually, Pennebaker had to talk to both Karpen and Grossman, after he didn’t film their set. Because Janis, when she realized that she had pulled off that performance and it wasn’t on film, she was devastated by it.

“She did another set for the camera later on and it was equally as great. All you have to do is look at Cass and Michelle in the audience. Pennebaker was shooting audience when she was on, and you could see the reaction of what was happening on stage was pretty much equal.

“I mean, Janis was fired up in the second performance because she now knew what impact she had on this audience. If Otis Redding got their souls and Ravi Shankar drove ‘em out of their seats, Janis tore their hearts out and leading this all-male band.”

Peter Lewis: Our [Moby Grape] debut album had just come out. We all went to a party thrown by Columbia Records head Goddard Lieberson. He had a turtleneck sweater and a little gold chain, with his hair combed down in front, and he didn’t have long hair. So he was trying to look cool. And, he had a party at his hotel, and I remember jamming with Paul Simon for a while. Tons of people. Janis was there because they wanted to sign her.

“Janis Joplin couldn’t get arrested before Monterey. Her trip was, one day everyone is kicking your ass, and then the next day everyone is kissing it. It does something to you.”

Richie Furay: We played with Otis Redding before, and he came to one of our recording sessions in New York. Dewey brought him. A great and nice guy and a very special man. Otis captivated an audience. Johnny Rivers, I’m telling you man, the guy is a talented guy. Janis Joplin she was a powerhouse at that show. Hendrix had charisma. I was taken back by Jimi Hendrix and the Who. What are these guys doing breaking their guitars, man? It cost me a mint to get my little guitar.

“I did feel a schism between the LA bands and the San Francisco bands. I mean, we were in their backyard. Jefferson Airplane, Moby Grape, some of the groups definitely ‘San Francisco’ oriented. They had the Fillmore and this big national stage that they worked from, and ‘we’re getting a lot of recognition and notoriety.’ There was some of that going on.”

Pete Townshend: It was exciting to go to San Francisco for the first time, but also quite strange.

This was a divine opportunity.

“Others may remember it differently. I couldn’t see how Grateful Dead, Janis Joplin or Country Joe could be taken seriously. Their sound was so ragged, so raw. I was used to a slicker sound.

“Now I see better what they were doing, and just like the Who it was not just about music, it was about message and lifestyle and change. The three bands I mentioned all had manifestos that were not just about the music. It took me a while to understand that. “Country Joe was of course a political balladeer– what’s wrong with that? Absolutely NOTHING – say it again. I saw quite a few acts, but I was really wound up, one of the few timesin my career that happened. “A side issue was that we played at the Fillmore on this trip, and that was probably more important to us, because Bill Graham insisted we play a longer set than we were used to. So we had to really begin to play proper music, like Cream I suppose. It was around this time we began to include songs like ‘Young Man Blues’ and ‘Summertime Blues.’”

Andrew Loog Oldham: Monterey was probably the nicest event I’d been to since I worked gofering at the 1960 Antibes Jazz Festival for the Les McCann Trio. The same sort of vibe and camaraderie, ‘aren’t we all so lucky to be here kind of thing.’ The two show stoppers for me were Otis Redding and Janis Joplin.

“I knew that the Who and Jimi Hendrix were reshaping the world at the same time but I was already familiar with them. With Otis I wondered how he felt playing to an all white audience in America. Janis was not my cup of tea, but she was undeniable. The same way that Pink Floyd would champion the era of brilliantly boring. Janis was the slag you never took home up there on stage lighting up the world. But what a cost?

“I remember her and Rick Danko of The Band in the 1970 Canadian documentary Festival Express, singing their very last drops. Janis died two months later.”

D. A. Pennebaker: Janis Joplin, Big Brother and the Holding Company were the one thing we were told we couldn’t shoot for the film [Monterey Pop, documentary released 1969]. Although I did shoot a little, but Grossman, who was just entering the Big Brother management picture said, ‘I’ll pull her the minute I see a camera going on her. All the cameras have to be pointed at the ground.’

“We went through a whole big drill and it got me really intrigued, you know, with this going on, and then when I heard her, the first song, ‘Combination of the Two,’ and I said, ‘Jesus Christ…This is impossible.’ So I went to Albert and I said, ‘Whatever it takes. I mean, we got to get her.’

“So he disappeared, and the next thing I knew Janis came out and she said, ‘Oooh, I’m gonna do it again and you can film me this time.’ So we did. [The band’s “Combination of the Two” is heard in the credits for Monterey Pop].

“I loved Janis and thought she was a fantastic person. And I always thought there was a film there and I shot a lot with her, but what was she was doing was so hard for her it was hard for me to film her.

“My father was a boozer. You can’t count on getting their real lives. You get something else. They put on a kind of a show. And that was a problem. And I had a problem with Janis. The drugs. And I had nothing against drugs because I didn’t know enough about them yet.”

Jerry Heller: Very time I saw Janis she blew my mind. I didn’t think anyone could sing like her. And she was so tiny, and you don’t realize how tiny she was with all her little feathers and stuff. Janis drank like a man out of the bottle. I saw her do a sound check at the Hollywood Bowl drinking a bottle of Southern Comfort. Man, but when she started to sing…” Guy Webster: The Monterey International Pop Festival was exciting. I took two photos of Janis Joplin. I met her backstage. I knew who she was. I had heard about them. Columbia Records was after her but really didn’t want her with the band, Big Brother and the Holding Company. That was upsetting to me. This is how she got started. We talked backstage and she had a dog under her arm and I wished her good luck. She was shy. Janis went on. “I heard her for the first time live. ‘Oh my God! What a voice.’ She was like another human being. It all came from inside. She was like the first white blues singer I could relate too. And I just loved her. And everybody went nuts. And that’s when all the record executives up there started picking up. ‘Holy shit. We better get this girl quick.’ Clive Davis got her. It didn’t bother me that sometimes the band with Janis was out of tune. This was organic. I really liked the whole performance and I was just sorry for the guys. ‘Cause I knew she was going solo. I had watched this sort of thing my whole life. “Later Janis would come to my studio in Hollywood. We allowed her to shoot an album cover there. I think the Pearl LP cover. I thought she had unbelievable soul.”

Roger Steffens: FM rock radio emerged in 1966 and was really blaring in ‘67. That year you had a revolution in radio. Before that, it’s hard to imagine that, except for a few effete hi-fi snobs and opera and classical music lovers, hardly anyone ever listened to FM radio. First of all, it cost so much to have an FM set, and there were hardly any FM stations, and whatever there were, they were invariably straight and uptight.

“KMPX-FM, [San Francisco] with Tom Donahue just revolutionized the airwaves, and then his work spread to the Los Angeles area on KPPC and later KMET. It was the most amazing radio. Entire albums on shifts, coupled with live concerts that had just occurred.

On November 2, 1967, the night before I shipped out for Vietnam, three Army buddies and I drove out of the Oakland Army Terminal across the bridge to Winterland in San Francisco.

“It was to be the debut of a new English band, but we were there to see the opening act, Janis Joplin and Big Brother and The Holding Company. I had grown up in the ’50s in NYC and had seen almost all the major figures of the era in Alan Freed’s big stage shows. But not since Jackie Wilson had I seen a performer of such soul-searing power as Janis that night. She was like an exposed nerve ending with a voice and I felt totally drained emotionally after her startling set.

“Then Richie Havens appeared in the middle of the huge dance floor, alone on a stool with his acoustic guitar, encircled by a couple of thousand kids. He held us in the palm of his hands for the next hour, after which Bill Graham came out on stage looking very apologetic. ‘I know you all came here tonight and paid three dollars to see three acts, but Pink Floyd can’t get out of Customs in time. So I went to the [local club] Hungry I and got the current group there to fill in. Ladies and gentlemen, please welcome Ike and Tina Turner!’

“Janis raced out of the dressing room clutching a full bottle of Southern Comfort, and worked her way to the foot of the stage, right beneath Tina, whooping and hollering encouragement all through Tina’s outlandish, heart-racing set, draining the bottle in the process.

“After that, Janis decided to do an unannounced second set, and to this day it remains my most precious musical memory. Indescribable, except to say it was twice as good as her astounding opening set, our minds completely blown.

“A few hours later I was on a plane to Saigon and the war, leaving the States with a vow that if I made it through the war alive, I would come back and live in the Bay Area. I did, and I did.”

Alex Del Zoppo: While still on active-duty in the Air Force (’65 thru ‘66) I had been to see the Dead and Big Brother, the Airplane and a few others from San Francisco. Some of them did a date in L. A. at the Shrine Auditorium. [Big Brother and the Holding Company and The Merry Pranksters] on January 15, 1967. I also went to the Monterey International Pop Festival as Sweetwater became a band.

“Sweetwater played a night with Big Bro in December 1967. It was the one that had all of the record company executives in to see them. However, we were also seen by so many of them all in one night, that a bidding war developed, eventually leading to us getting signed by Mo Ostin at Warner Bros/Reprise – just from that one gig.

“Janis and the guys were amazingly cool to us newbies – Albert [Moore] and Janis shared a love for Southern Comfort, as it turns out!”

Rodney Bingenheimer: The week before the Monterey International Pop Festival I had met Jimi Hendrix with Janis Joplin in Hollywood at a party at Jimmy O’Neil’s house. Jimmy had hosted Shindig! and was a big LA deejay, too.

“I saw Janis on the street in Haight Asbury and hung out with her, and caught Janis and the band play at the Avalon. One time at another concert she ran up on stage and ‘comically’ said, ‘Sorry I’m late. I was having sex with one of the Chambers Brothers!’ “I knew Chet Helms in L.A. I met him early on when he worked with Janis, and he let me into the ware house at the Avalon to get some concert posters which I still have. Chet was a hero, and was for the people. Later in 1967, or ’68, the group started playing for Bill Graham at the Fillmore. “I went to their recording sessions at Columbia studios in Hollywood on Sunset Blvd. with Genie the Tailor [Jeanne Franklyn] when they were recording Cheap Thrills. It was an old radio studio that was built in 1938 and comedians like Jack Benny, Red Skelton, George Burns and Gracie Allen used to do their radio shows. Columbia was like a ship with round portal windows. I know it had one of the first 8-track tape machines in Hollywood “In the mid-sixties the rock acts on Columbia were in the studio. Like the Byrds, Chad & Jeremy, and Moby Grape. Donovan recorded some of his Sunshine Superman there in 1966. Janis and the guys were nice people.”

Cheap Thrills was recorded at CBS studios in New York and Hollywood. The long player housed compelling originals (“I Need a Man to Love,” “Combination of the Two”) as well as covers of jazz and blues favorites (George and Ira Gershwin’s “Summertime,” Big Mama Thornton’s “Ball and Chain,” and, notably, “Piece of My Heart,” a now-classic soul ballad, penned by Jerry Ragovoy and Bert Berns, that became one of Joplin’s signature songs and her top charting single during her lifetime. It was Jack Casady from Jefferson Airplane who suggested to Janis that she cut it.

The LP was produced by John Simon and engineered by Fred Catero.

Simon had seen Big Brother and The Holding Company at the Monterey International Pop Festival.

In the mid-sixties Simon had apprenticed under Columbia Records president Goddard Lieberson. He engineered classical recordings and Broadway cast shows productions with songwriters such as Richard Rogers, Stephen Sondheim, and Noel Coward.

During 1967, Simon, along with John Hammond and Bob Johnston, co-produced the debut Leonard Cohen album, The Songs of Leonard Cohen.

“Lieberson decided to add rock to the Columbia catalogue after the Monterey International Pop festival,” wrote Simon to me in a 2014 email. “Lieberson was a real class act, English and all. Funny, urbane, a classical composer, charming.

“Columbia had a sort of ‘caste’ system (being unionized). You were either a recording engineer like Roy Halee, who did most of the ‘rock’ stuff, Frank Laico, or Fred Plaut. Or you were a mixing engineer, like Fred Catero, at first, and a half dozen others. Then, Fred, talented as he was, moved up to be a recording engineer.”

The head of Columbia engineering, Eric Porterfield, designed all-tube hand-built consoles from the former radio rooms.

“Columbia studios had a custom Ampex 8-track, a live chamber and Altec Lansing A7 speakers. ‘The Voice of the Theatre,” Catero explained to me in a 2014 interview. “For microphones I used a U47 and maybe a SM57 on lead vocals. The Columbia studios had great natural echo, reverb and leakage. And you wanted that. In fact, it added to the drama. Also, I knew the rooms and where the best place was for piano or bass or the singer.

“The arrival of FM radio in 1967 didn’t change Columbia Records but the demographics of FM radio changed the label and who was listening, because FM is ideal for high fidelity. As a human organism, we rely a lot on the subtleties, and FM was able to transmit that—especially if you were listening on headphones or a good system—whereas AM was limited in its ability to transmit that feel.”

In 1968, Simon produced the innovative first LP of the Al Kooper-led Blood, Sweat and Tears, Child Is The Father to the Man, and, then in the same year The Band’s epic Music From Big Pink.

“I came to Columbia Records in 1967, after the June Monterey International Pop Festival where I had been assistant stage manager. I assembled BS&T and joined the label as a staff producer,” volunteered multi-instrumentalist Kooper in a 2008 interview with me.

“As far as Columbia in England, they understood what was being done from the label in America in 1967 and ’68.

“Simon & Garfunkel’s Bookends, Dylan’s John Wesley Harding, Songs of Leonard Cohen, the BS&T album, and Cheap Thrills. The Columbia label had a real grasp on the music that was being made. FM radio was a factor.”

The raw, ragged and delicious Cheap Thrills spent a combined total of eight weeks atop the Billboard 200 in two runs during October, November and December of 1968.

Heather Harris: Martin Scorsese used the rousing rocker “Combination Of The Two” by Big Brother and the Holding Company in his best sound track film Bringing Out the Dead, (1999) to encapsulate two out of control professionals on the move at the speed of light. No one says “completely crazy” quite like actor Tom Sizemore, and his character’s partner Nicolas Cage was dealing with the life and death import of their job as ambulance medics by trying it Sizemore’s way for a night, in this case completely nutso. ‘Combination’ was the stone cold consummate choice for this scene, even if it features less of lead singer Janis Joplin in this track. That particular band and her WERE out of control professionals, delivering life affirming songs and shrieks despite the reminders of everyday mortality. Perfection!

‘”Combination Of The Two’ began the second album by Big Brother And the Holding Company, Cheap Thrills with the equally legendary artwork by prototypical San Francisco psychedelic cartoonist R. Crumb. It fit the era of coordinated act and art as superbly as the Sgt. Pepper cover had and was just as original.

“In a better universe, Janis should have had a long career as not only a topflight interpretive singer but also patron saint of undervalued women who achieve. What does it do to the psyche for a young girl to be voted ‘Ugliest Man on Campus’ by her so-called student peers? In her case it became source material. That’s how someone in their teens and mid-twenties mustered the moxie to sing of pain with breathtaking exactness of emotions.

“Janis Joplin is one of the few dinosaur era legends always embraced by each succeeding generation. Her ability to transmit the universality of pain transcends all the folklore of the 1960s.

“I never had the pleasure to see or photograph her, but my husband Mr. Twister said she was the only act he’d ever seen wherein immediately after one of her heart-wrenching showstopper ballads the audience was stunned into awestruck, hear-a-pin-drop silence. He only saw her at the Shrine Exposition Hall in Los Angeles and the old Fillmore in San Francisco. I wonder which of the two audiences proved that reverent?”

Chris Darrow: The Summer of Love was real. It had a real vibe, a real feel and a real tone….all of which added up to something none of us had ever experienced or seen before. It was in the air. The original nature of the psychedelic movement was never really about the drugs or just having fun. For the devout, it was about expansion; spiritual, mental and physical. The idea of self-realization, freedom and growth gave the burgeoning hippie movement a direction. Having come out of a more introspective and cool scene, called the Beat Generation or beatniks, the new cool kids wanted to rock, but in a free and open way.

“By the end of the summer things had changed and bands started getting hits and royalties started rolling in. The California phenomenon had gone from Flower Power and pot to money and bad acid. The Monterey International Pop Festival marked, to me, the beginning of the acknowledgement of big money in the equation.

“East coast entrepreneurs like Albert Grossman came to see what was going on. Jimi Hendrix broke it open. Janis Joplin became the queen. Otis Redding proved he was the best. But after the festival there was a sense that things had changed and would never be the same.

Jan Alan Henderson: I had graduated from Hollywood High School in June 1968 when I decided to venture to the Kaleidoscope (formerly the Hullabaloo) in July ’68 to see Big Brother and the Holding Company. I had seen film on the band, so I kinda knew what to expect. Film and live are two different things!

“What I witnessed that evening was spellbinding. Janis’s voice expressed the anguish of a generation trying to find its feet, only to be blown away by its own hot air.”

John Van Hamersveld: I met with Bill Thompson, the new manager of Jefferson Airplane, at the Pinnacle White House in Los Angeles. He wanted to talk to me about an album cover to be created for the band.

“Bill Graham had lost his deal with them in his own confusion of the times. Thompson was packed with energy to take the challenge. I had already met Grace Slick, and the band had done a Pinnacle show and my poster had been distributed and was a hit.

“One night, Grace Slick and Paul Kantner of Jefferson Airplane stopped by my house on smiles. They give me a lid to keep me going while I work on the design for their upcoming Crown of Creation album in July of 1968.

“I place the memory of this unbelievable evening in my precious suitcase of dreams. The idea of creating this album cover sends me higher into a new orbit of ecstatic possibilities. I realize I’m part of the underground media in the new cultural revolution. At the age of 26, I’m recognized as an independent creative director. Far out!!

“Flashback to December 31, 1967: Winterland Ballroom, San Francisco, for Bill Graham’s Doors’ concert. I checked out the show backstage with The Family Dog poster artist Stanley Mouse. His best friend, Bob Seidemann, the captor of Janis Joplin’s most memorable images, arrived. He escorted Janis, the rock goddess herself, along with the extraordinarily beautiful Grace Slick. It was almost midnight. The Doors and Jim Morrison were on stage with the music as a roar of a jet plane.

“We slipped in between the curtains and created our own New Year’s Eve party. Drinks and puffs were shared. We constantly checked our watches – when you’re stoned, time isn’t the only easy thing to lose. As midnight arrived, the audience cheered, and we all kissed and embraced.

“During late 1967 and through ’68, I was the co-promoter with two partners of the Pinnacle Dance Concerts in Los Angeles at the Shrine Exposition Hall and drew and designed the event posters.

“We would book Big Brother and The Holding Company, and they would stay at the Hollywood Landmark Hotel on Franklin Ave.

“Albert Grossman had a young manager from New York City with the band at the time. The Big Brother group would bring Janis to the shows. After her set with the band still on stage, she would leave the stage and run to the back of the Shrine Hall, into the audience, all in a sweat, her skin was like purple and reddish pink, like neon, the rough surface of her complexion, crazed and exhausted.

“She then goes to the couch in the dressing room and finishes off the bottle or two of Southern Comfort and passed out. As the group reorganizes, we would want to go to parties after the two shows. The band would pick her up and put in the car and in a couple of cars we would arrive at a party and someone picks her out of the back seat, and takes her into the party and put on the couch.

“The party would go through the night and Janis would be passed out. At the end of the party, she would be moved to another couch, back seat, or the next party, or back to the hotel, always passed out.

“The Pinnacle poster for our Shrine concert with Albert King and Pacific Gas & Electric I assigned to Rick Griffin and Victor Moscoso. The poster is their beginning of the ZAP style with R. Crumb, their first comic strip.”

Denny Bruce: I managed Albert Collins who was headlining the Whisky a Go Go.

Mario Maglieri who ran the club with Elmer Valentine gave me a booth near the door. It was a packed house. I’m in booth, alone. Janis and Howard Hessman who was in The Committee came in and they sat down. She ordered champagne and other cocktails. Janis loved Albert and said ‘That motherfucker should be in my band!’ They left. The tab came to me… Mario said ‘Come into the office…’ He thanked me for having ‘star power’ in the booth. ‘It’s good for his business…’”

Dan Bourgoise: I managed the band Southwind who opened for Janis and I watched her entire set while leaning on an amplifier onstage. I would see her as she turned back to face the band. Awesome.

Stephen J. Kalinich: I hung out with Janis twice. She was friendly and it felt electric. Once in a waiting room in an office of a booking agent on Sunset Blvd. We were alone. It was very flirty. I recited a few poems to her. Janis had a free spirit beatnik vibe. She didn’t have an entourage.

“Janis loved my poem ‘The Magic Hand.’ I was new in California. I was doing poetry readings, including a couple with this flamboyant character named Esquerita who once had a record out on Capitol. Janis came to a poetry recitation I did in Hollywood in a room on Santa Monica Blvd and Hudson Ave.

“I was a staff songwriter 1966-1969 for Brother Music and The Beach Boys were doing the album 20/20 at Columbia studios on Sunset and Janis was doing some tracks with Big Brother around 1968.

“Later on in the fall of 1970 I was mixing ‘World of Peace’ a recording I wrote with Brian Wilson at Sunset Sound while Janis was working with producer Paul Rothchild. It was an exciting time to be in Hollywood.”

Skip Prokop: The Paupers played at Monterey but it didn’t go well. Albert Grossman was our manager. And because of our failed effort, we didn’t even make the Monterey Pop movie. Janis knocked my socks off at Monterey.

“In 1968, after Monterey, Al Kooper and Mike Bloomfield wanted me to be in The Live Adventures of Mike Bloomfield and Al Kooper super session album in San Francisco at the Fillmore. I later moved to the Bay Area. Bill Graham loved The Paupers and he basically took a liking to me. Bill had Janis jamming a lot at the Fillmore with all kinds of other musicians.

“Albert asked me to put Janis Joplin’s new band together. And at that point I was seriously thinking about leaving The Paupers. And Albert said, ‘Look man, you are a task master. You put great, great bands together. I want you to put Janis’ band together.’

“So what that led to was Janis and I did a lot of hanging out. And just to see what she would be like doing some Aretha Franklin stuff and stuff that got away from the Big Brother acid rock.

“We actually went into the RKO studio, two of us from The Paupers, and someone else that we brought in at the time and actually recorded a whole bunch of material with Janis. We did a bunch of Aretha, ‘Hey Joe,’ a whole pile of material over three nights.

“To go into the studio with her…That was a buzz and a half to play with her in a studio, to spend time with her just ripping around in her car and getting to know each other.”

Richard Bosworth: July 13, 1969 I jumped the fence and snuck into Kennedy Stadium in Bridgeport Connecticut to see new super group Blind Faith’s second American concert. Opening acts were Irish band Taste with Rory Gallagher on guitar.

“Next up a new group mistakenly billed as Bonnie & Delaney & Friends which included Eric Clapton’s future Dominoes Jim Gordon, Carl Radle and Bobby Whitlock. Also Leon Russell, Bobby Keys, Jim Price and Stevie Winwood’s former partner in Traffic, Dave Mason on lead guitar.

“Though I didn’t pay to get in I had the best seat in the house. Front and center with the stage was only a foot high so one could sit down. I was no more than a few feet away from everyone who performed that night.

“During Bonnie & Delaney’s set I noticed Sam Andrew and Janis Joplin standing at stage left intently watching their performance. She was wearing a white bell bottomed outfit, dancing along and digging it. I think she was impressed with Bonnie Bramlett and as it was just after parting with Big Brother she probably thought ‘This the kind of band I need!’

“Saturday night at Woodstock ’69 in August was prime time and a tour de force of San Francisco rock groups including Santana. Creedence Clearwater Revival, Grateful Dead, Country Joe, Sly & The Family Stone

and Jefferson Airplane.

“At midnight Janis Joplin performed with her new Kozmic Blues Band. She was in good form and seemed to enjoy singing with a rhythm and blues band. All the acts were taken aback by the size of the crowd and at one point Janis paused while looking out at the audience and said with a quiver in her voice ‘I had no idea there were so many of us!’”

Nancy Rose Retchin: At the Texas International Pop Festival [August 30-September 1, 1969]. I saw Janis Joplin and she was delightful. The promoter was Toby Roberts.

“I remember Dallas that summer. Lots of bugs and in North Texas Dallas they have a breed called chiggers. In ’69 there was a chigger infestation for that part of the country. My friend Pat and I had to spray insect repellant on Janis’ legs.”

Tina Turner: Mick Jagger came to the States in 1969 and asked us to tour America with him later in the year. We played the Forum, Madison Square Garden, and all the big arenas. Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin were at the New York show. [Joplin joined Ike & Tina Turner on their November 27, 1969 appearance]. I like them to remember what they have just seen. I’ve never really thought of our show as being aggressive. Even as wild as I am I know that I maintain my femininity.

“Like Vogue said it best: ‘They came to see Mick Jagger but they saw Ike and Tina and they’ve been comin’ ever since.’ From there on we crossed over to the pop market and it’s been that way ever since.”

Elliot Mazer: I recorded Janis Joplin and Neil Young and used the Wally Heider remote truck. A tube board, called the green board that Neil eventually bought. I had used it with Richie Havens and with Janis at Winterland. That board had done a lot of wonderful things. Janis on stage and Janis in the studio were the same. Once she started singing, she sang. A wonderful performer.

“Janis and Neil are extraordinary people. I mean, they are unique and sound like nobody else. They were doing something that was really original and people either liked it or didn’t pay attention. I think Neil and Janis were really smart people. Above average smart people. You don’t become the success in this business without being really bright, by the way. You can’t do it all. And Janis and Neil would do it all.

“Janis was really interested in every aspect of making records. People keep referencing her sexuality. But in fact, she was an incredibly smart person that would really care about something and would work incredibly hard.”

On August 6, 1970, Janis Joplin, Steppenwolf, Johnny Winter and Poco performed in New York at Shea Stadium for The Concert For Peace. The event was organized to acknowledge the 25th anniversary of the dropping of an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan.

Two days later on August 8th Joplin purchased a headstone at the Mount Lawn Cemetery in Philadelphia, PA., to mark the grave of singer Bessie Smith, who Joplin cited as her biggest

influence. Smith died in 1937 following a car crash near Clarksdale, Mississippi. It reads “The Greatest Blues Singer in the World Will Never Stop Singing.”

Chrissie Hynde of the Pretenders once commented on Janis Joplin for a Joplin released package of her catalog work now reissued on Columbia/Legacy Recordings, a division of Sony Music Entertainment.

Hynde attended a Joplin concert at the Blossom Music Center in Richfield, Ohio in 1970.

“The thing about Janis is that she just looked so unique, an ugly duckling dressed as a princess, fearlessly so. Seeing her live was like watching a boxing match. Her performance was so in your face and electrifying that it really put you right there in the moment. There you were living your nice little life in the suburbs and suddenly there was this train wreck, and it was Janis.”

In an interview with Hynde in 2002, I asked about her approach to covering a song and if it was different to a tune she had written and sung on stage.

“Not particularly. In some ways it’s fun because it’s different and I can interpret one of my favorite songs, which is great. It’s like a freebie. There are hundreds of fantastic songs out there and we can do any of them and we’re free to do whatever we want. That’s a great thing.

“Obviously, singing my own songs I’m expressing myself, but I would only sing a song that I feel. Anyone who can relate to a song will enjoy singing it. To interpret it my own way – I would never cover a song and do it if I didn’t think I could give it a ‘Pretenders-esque’ twist, or lend something to the song.”

“My initial exposure to Janis Joplin was, not surprisingly, every bit as visual as it was musical,” recalls then-budding rockin’ pop connoisseur Gary Pig Gold, “thanks to a most timely after-class Film Arts Dept. screening of Monterey Pop in the school auditorium mere weeks before the woman’s death. And while that landmark little movie first put fully motioned pictures to the beloved Hendrix and Who material I’d already spent untold hours beneath teenaged headphones with, I must admit Janis and her Big Brothers’ Monterey footage just didn’t strike me back then as all that kozmic whatsoever, in any way.

“At first, that is.

“Perhaps because the ‘funkiest’ [sic?] I’d ever allowed myself to get up to that point was Micky Dolenz’s proto-rap ‘Goin’ Down’ on the Canadian RCA ‘Daydream Believer’ flip side, I can only guess from a half-century’s rearview. Or maybe it was Janis’ decidedly un-pin-up persona which, like the upper parts of her vocal register, simply slashed all too violently against the comparatively genteel Dusty, Lesley, and Lulu stylings I’d been accustomed to up to that point. Then, even subsequent study of my pals’ Joplin LPs failed to impact or impress in the least either: why, even at that young an age I couldn’t help but wish Sam Andrew would tune his humbuckin’ SG for starters!

“But a couple of years later, accompanying a through-and-thorough fan(atic) to a midnight screening of the 1974 Janis documentary, I suddenly experienced a tinge of empathy as the subject matter recounted therein the utter despair in braving her Thomas Jefferson High School ten-year reunion – damn, could I relate! – plus I suddenly noticed that, when push failed to shove (thanks to producer Paul Rothchild) the lady could settle down fully into song if challenged, and coached, accordingly (I speak of Bobby McGee of course).

“Duly intrigued, said screening sent me immediately to the nearest record store to pick up the Janis soundtrack album, one full half of which consisted of over a dozen authentically Austin ‘Early Performances’ which revealed yet another facet of the woman’s musical prowess: Yep, she’d obviously been listening to, and cannily absorbing as much Odetta and Dylan vinyl as she was Otis ‘way back then I realized …prior to returning to San Francisco to hammer her own trail that is.

“Most recently, Amy J. Berg’s Janis: Little Girl Blue fleshed out even more fully the short but sharp life I may have dismissed just a twee bit too easily upon first hearing and seeing that scratchy Monterey footage back in 1970. And while I’ll still state, firmly for and on the record, that to my ears Gerry Marsden’s Pacemaking ‘Summertime’ does Gershwin much prouder than Cheap Thrills ever did, I do wish Ms. Joplin could have stuck around a few years, and even a few albums, longer. If only to settle, once and for all, all those tall tales about her full tilt boogie with, I kid you not, Dick Cavett.”

Dr. James Cushing: Ellen Willis wrote that Janis Joplin ‘was second only to Bob Dylan in importance as a creator/recorder/ embodiment of her generation’s history and mythology,’ adding that she achieved her importance in “what was basically a male club.” [Out of the Vinyl Deeps, 2011, p.126] In her performances, Joplin transformed the public perception of what a woman can do.

“She certainly dominated Cheap Thrills more thoroughly than Grace Slick dominated any of the Jefferson Airplane LPs, turning the first achieved Big Brother album (not the Bob Shad-produced false start) into a vivid example of what a great blues belter can achieve: the erasure of category.

“Is Cheap Thrills rock? Soul? Jazz? Blues? Yes! ‘I Need a Man to Love,’ ‘Summertime,’ ‘Piece of My Heart’ (originally done by Aretha’s sister Erma) and ‘Ball and Chain’ float above all those genre categories without being defined by them. They become Janis Joplin music.

“With FM radio you could really investigate sound between your ears. Of course, stereo sound made a big difference here too. Stereo LPs cost a dollar more in 1967, but stereo added a whole other dimension to the discovery. Poet William Blake said, ‘One thought fills immensity.’ In the headphone experience, the music becomes the one thought.

“FM radio proved that we are not alone, that there were live people who could talk to me in my own home. In my own room, who at the same time could function in this larger, more exciting culture where adults had the great grand permission to be who they really were.

“Jefferson Airplane was not the fantasy. The fantasy was the Harvard School, a fucked up 1940s’ way of living in the world. The reality was a lot closer to Jerry Garcia. The reality was a lot closer to Grace Slick, Janis Joplin and John Lennon. The reality was that I was going to go to U.C. Santa Cruz, which would ultimately house the Grateful Dead’s archives. FM radio showed me and others there were new voices and choices available.

“I saw Janis on stage only once, with her Full-Tilt Boogie band, in early September 1970 at Howard Stein’s Capitol Theatre in Port Chester New York.

“I have never before or since witnessed a musical performance that made me worry for the health and safety of the performer. She pushed her voice and body as hard as humanly possible for over two hours — on a 1-to-10 scale, she began at 10 and stayed there the whole show — and I remember thinking, at the moment she howled out ‘Ball and Chain,’ how can this woman maintain this level of intensity? She’s going to sing and dance herself to death!

“Corporate censorship sucks by definition, but Cheap Thrills is a much better album title than Sex, Dope, and Cheap Thrills. Two one-syllable words with self-deprecatory humor: perfect. Five words that together read like a scare-headline in some conservative paper? Extra trouble. And the idea of dope may be implied.”

Celeste Goyer: Watching Janis in the Monterey Pop film reminds me that cultural lag hits trailblazers the hardest. The low skies of the early 60’s, and even the 50’s, seem to be responsible for a lot of her heartache. Nobody could have given more of herself in a performance—she turned herself inside out to give it all—but giving it all is what the woman is expected to do.

“Meanwhile the public appetite gets bigger, but only for the meal they’ve eaten before. Meanwhile the woman goes back to her hotel room alone and is running at such a deficit of her unmet needs versus what she has to put out to feed the beast that she says she doesn’t know how the music life could work at all without drugs.

“Like watching an exquisitely beautiful film with a relentlessly tragic storyline, when watching Janis on film, I find myself continually switching between empathy for her disappointment and emotional exhaustion and grateful disbelief for the tornado of expression she allowed to come through her voice and body.

“A good goal for an enlightened society, it seems to me, could be reverse-engineered by figuring out what a world would look like where Janis and Jimi could be happy and productive into their ninth decade.”

Daniel Weizmann: If Janis was merely a high-octane blues wailer, she would still be great but she wouldn’t be a legend. What makes her persona so arresting is what’s underneath but never out of view: the Plain Jane All American girl, the homely daughter of a Texaco engineer.

“Without her flower power garb and her blistering, lurching body language onstage, without her projection, she could be any girl from Anytown, USA. The shy one sitting in the back of class unnoticed, trying in vain to camouflage her acne.

“So when you watch her perform, you’re not just watching a singer. You’re watching a transformation of epic proportions.

“If what Alfred Alder says is true, that there is no such thing as talent, only pressure, then Janis was contents under extreme pressure. She brought the full force of her outsiderness, her anonymousness right up through her kishkes. It’s poignant and heroic that she blazed the trail for the Wilson sisters, Stevie Nicks, and a zillion other glamorous beauties that followed.”

Sherry Hendrick: Flying out of years of politico change-the-perception sixties through a cannon of fireworks to land solo in the questions of our inner soul in a blindingly bland 1970, and there’s Janis, put on a side again, giving you the deep solo blues on a path that always comes down to one’s own. Sorrow that feels so good, because she’s riding it on a V-8. This is true, but I ain’t going to sit down for it.

“She was a salve for the repressed 1970s and coming into womanhood. With power, no matter what they say, raped, working double time in a man’s world, riding on Janis’ voice and phrasing. Pause hanging in the air and barrel forward.

“Tracy Nelson, Carole King, Laura Nyro, Joni Mitchell and her Blue, and Janis Joplin. Those were our pills, but Janis harnessed power and threw it back to us.”

(Harvey Kubernik is the author of 19 books, including Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972. Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. For 2021 they are writing and assembling a multi-narrative book on Jimi Hendrix for the same publisher.

Otherworld Cottage Industries on July 30th published Kubernik’s 508-page book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters, featuring Kubernik interviews with D.A. Pennebaker, Albert Maysles, Murray Lerner, Morgan Neville, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, Andrew Loog Oldham, John Ridley, Curtis Hanson, Dick Clark, Travis Pike, Allan Arkush, and David Leaf, among others.

Kubernik’s writings are in several book anthologies, most notably The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski. He was the project coordinator of the recording set The Jack Kerouac Collection.

During 2006 Harvey Kubernik spoke at the special hearings initiated by The Library of Congress that were held in Hollywood, California, discussing archiving practices and audiotape preservation.

In 2020 Harvey served as Consultant on Laurel Canyon: A Place In Time documentary directed by Alison Ellwood which debuted om May 2020 on the EPIX/MGM television channel.

Kubernik has just penned a back cover book jacket endorsement for author Michael Posner’s book on Leonard Cohen that Simon & Schuster, Canada, will publish in October 2020, Leonard Cohen, Untold Stories: The Early Years).

Kubernik’s 1995 interview, Berry Gordy: A Conversation With Mr. Motown appears in The Pop, Rock & Soul Reader edited by David Brackett published in 2019 by Oxford University Press. Brackett is a Professor of Musicology in the Schulich School of Music at McGill University in Canada. Harvey joined a distinguished lineup which includes LeRoi Jones, Johnny Otis, Ellen Willis, Nat Hentoff, Jerry Wexler, Jim Delehant, Ralph J. Gleason, Greil Marcus, and Cameron Crowe.

Kubernik’s 1996 interview with poet/author Allen Ginsberg was published in Conversations With Allen Ginsberg, edited by David Stephen Calonne for the University Press of Mississippi in their 2019 Literary Conversations Series).