By Harvey Kubernik © 2025

Bob Dylan’s 2025 tour concludes September 19th in East Troy, Wisconsin.

On June 27th, Columbia Records will release Barbra Streisand’s album of duets, The Secret Of Life: Partners, Volume Two. Barbra and Bob team on a rendition of “The Very Thought of You.”

In My Name Is Barbra, her 2023 autobiography, Streisand mentioned receiving a communication from Dylan.

“Back in the 1970s he sent me flowers and a charming note, written in colored pencil with childlike letters, asking me if I would like to sing with him.”

When the Streisand-directed Yentl was due for theatrical release in 1983, Dylan sent a copy of Infidels to Barbra, indicating he was looking forward to watching the film, and wanted to work with her.

“You are my favorite movie star,” Dylan wrote. “Your self-determination, wit and temperament and sense of justice have always appealed to me.”

On May 14, 2025, Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band opened their European tour at the Co-op Live in Manchester England. Bruce closed the show with Dylan’s “Chimes of Freedom.”

Dylan (birth name Robert Allen Zimmerman) had been a Cash fan since the very late 1950s, when, as a teenager, he hitchhiked the 75 miles from his Hibbing, Minnesota, hometown to Duluth and paid $2.00 to see Cash and the Tennessee Two at the Duluth Amphitheater.

On February 6, 2015, when Dylan was honored at the 25th anniversary MusiCares 2015 Person of the Year Gala at the Los Angeles Convention Center, he praised Cash in his stage remarks.

“Johnny Cash recorded some of my songs early on, too. I met him about ’63 when he was all skin and bones. He traveled long, he traveled hard, but he was a hero of mine. I heard many of his songs growing up. I knew them better than I knew my own. ‘Big River.’ ‘I Walk the Line.’ ‘How High’s the Water, Mama?’ I wrote ‘It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)’ with that song reverberating inside my head.

“Johnny was an intense character, and he saw that people were putting me down [for] playing electric music. And he posted letters to magazines, scolding people, telling them to ‘shut up and let him sing.’ In Johnny Cash’s world of hardcore Southern drama, that kind of thing didn’t exist. Nobody told anybody what to sing or what not to sing.”

May 24, 2025 is Bob Dylan’s birthday.

From 1975-2025 I’ve conducted interviews with people about Dylan’s career.

Johnny Cash: I became aware of Bob Dylan when the Freewheelin’ album came out in 1963. I thought he was one of the best country singers I had ever heard. I always felt a lot in common with him. I knew a lot about him before we had ever met. I knew he had heard and listened to country music. I heard a lot of inflections from country artists I was familiar with.

I was in Las Vegas in ’63 and ’64 and wrote him a letter telling him how much I liked his work. I got a letter back and we developed a correspondence. We finally met at Newport in 1965. It was like we were two old friends. There was none of this standing back, trying to figure each other out. He’s unique and original. I keep lookin’ around as we pass the middle of the 70s and I don’t see anybody come close to Bob Dylan. I respect him. Dylan is a few years younger than I am but we share a bond that hasn’t diminished. I get inspiration from him.

Leonard Cohen: I came to New York City in 1966 and was unaware of what was going on at the time. I had never heard of Phil Ochs, Bob Dylan, Judy Collins or any of these people, and I was delighted, overwhelmed and surprised to discover this very frantic musical activity. Producer John Hammond was extremely hospitable and decent. He signed me to Columbia Records.

I liked the work Bob Johnston did with Dylan, and we became good friends. Without his support I don’t think I’d ever gain the courage to perform.

Patti Smith: The Bob Dylan Live 1966 Royal Albert Hall record. I can tell you this. I saw Bob Dylan in that period. I saw him right before he went to England (in 1966). I was really lucky. I saw him in 1963 when Joan Baez introduced him. I saw him through various changes. Then when he started wearing a jump suit, this lion-like hair and had a band, The Hawks, behind him. I saw him booed by the people even though he was really great. When I hear that record, I see him in my head because I can remember when he sang “Visions of Johanna” acoustically for the first time. He said, “This song is called ‘Seems Like a Freeze-Out.’” He didn’t have that title, you know. So, when I listen to that record it’s almost like a visual experience for me.

Martin Lewis: The sixties actually began in Britain in January 1963. Just as the Beatles were starting to please, please us – we drew our first breath of Bob Dylan. He appeared as the Greek chorus in an adventurous British TV play Madhouse on Castle Street. He sang “Blowin’ In the Wind”. It’s first broadcast anywhere in the world.

For this young English lad this was a heady time. “Please Please Me” made my head explode with the fizz of its joyously ascending climaxes. While Dylan’s anthemic “The Times They Are a-Changin’” lifted my soul. (As the late Ian Whitcomb remarked: Dylan was the world’s foremost “g-clipper”)

The sixties also ended in Britain. Six decade-long years later in August 1969. (Altamont that December was merely the burial). And just like its dawn, the twilight also featured Dylan and the Beatles. (Well – all except Paul). They all congregated on our Isle of Wight. Like Woodstock (two weeks earlier) but less hype and mud – more music. Dylan performed as the grand finale. It was his concert comeback after three years as the jester in a cast on the sidelines. The Marching Band’s John, George and Ringo communed backstage and in the VIP enclosure in front of the stage. (And yes – this teenage Artful Dodger managed to bullshit his way briefly into that cloistered sanctum to bear witness. And to scoff some free nosh…)

Dylan flouted all the festival rules. Most people that season were wearing denim or tie-dye. Dylan wore a suit. A white one. Just like Lennon’s Abbey Road clobber. Some sets – eg the Who, Joe Cocker, Moody Blues – ran expansive lengths. Dylan’s set on the final night at 11pm was a tight, trim hour. But he crammed in hits and deep cuts. Mainly fresh interpretations.

It was the prelude to the Never-Ending-Tour and the Always-a-Changin’ arrangements. 15 songs. From “She Belongs to Me” through “The Mighty Quinn” (then a recent UK hit for Manfred Mann) in a brisk 60 minutes. Among the many highlights I recall a sublime “Lay Lady Lay.”

Some contemporary press reviews claimed the crowd of 150,000 felt short-changed by Dylan’s set. I don’t recall that as the collective mood. It felt like a benediction on the decade.

Incidentally, fourteen weeks later I was also witness to the exorcism of the decade – Lennon’s historic Plastic Ono Band concert at London’s Lyceum Ballroom. He played a searing “Cold Turkey” and then it was all over now baby blue… The sixties… the whole caboodle… The Dream Was Over.

Dylan’s sensibility left a huge mark on me. And when I eventually graduated from Artful Dodger to Artful Producer, I kept dipping into his songbook. I’m still dipping…

To paraphrase from the Dylan song, I produced with Pete Seeger (his last recording) – Dylan has kept my heart always joyful.

Bob: May you stay forever young…

Mick Farren: The weight of anticipation that was loaded upon the release of John Wesley Harding was probably more than any artist should be expected shoulder. How in hell was Dylan going follow something as monumental as Blonde On Blonde? And in the landscape that I inhabited, not only were fans, musicians, writers, and rock critics asking the question. So were individuals who had regularly spent entire Sunday afternoons skulled to Neptune on the best obtainable acid listening to “Sad Eyed Lady of The Lowlands” over and over again, searching for some nebulous electric dharma of their own imagining. And when the answer turned out to be relaxed, controlled and even reserved, conflict broke out between those how just wanted more, just B-on-B 2, and others who were frankly baffled and studied the cover photo for mystic clues. Acidheads did not come to blows, but they glared at each other with their third eyes. Me? I accepted what I was given, and then I learned to love it. So, we had no more recklessly complex, declamatory monoliths like ‘Like A Rolling Stone.’

Dylan had constructed cottages; neat formal songs that smelled of Jerry Lee Lewis, Sam Phillips, Hank Williams and A.P. Carter. He had edited and simplified, and in so doing had created tunes that, down the years, proved to be of incredible durability. Think of all the songs from JWH, that are still covered, to the point that “All Along the Watchtower,” the song itself, can, in 2007, function as a crucial, cliffhanging, metaphysical, deep-space entity in the TV sci fi cult series Battlestar Galactica. I learned a long time ago, that with Ol’ Bob that the only answer to shrug. Go figure.

Brian Wilson: I was a fan of Bob Dylan in 1965. I like him. We did a song of his on the Beach Boys’ Party! I thought Dylan’s voice was an interesting voice.

Stan Ridgway: If someone doesn’t like Bob Dylan, I tend not to trust them somehow. On my album, Black Diamond, I did a version of Dylan’s “As I Went Out One Morning” from the John Wesley Harding album. The biggest influences on my songwriting are Bob Dylan and Tom Waits. It’s such an influence on me that I’m almost self-conscious about talking about it. I really think to a point, with Dylan, we’re literally living in a time when Shakespeare is alive and he’s right there if you want to go see him. He’s changed the popular song so much, and he had so much to do with that. He’s still here. His influence is so wide-ranging, how everybody writes like that now. It’s hard for a lot of people to realize how much he changed things. He sang his own songs. He broke the game open.

Anthony Scaduto: As a police reporter, I got turned onto rock because I was assigned to cover the Brooklyn Fox, where the kids were ripping up the seats over Little Richard. Rock hit, and I got into it a great deal.

Then Dylan came into the Village. Originally, I hated him…but soon my sentiments toward the man and his music became quite positive. I felt that rock was, and still is, and important part of our culture. Even though I’m older than most of the rock writing fraternity, I felt there was a so-called message there, and it was saying something to Western society.

My editor suggested I write a book on rock, since Lillian Roxon’s Rock Encyclopedia was selling quite successfully. I said, “Dylan, of course,” since I had always wanted to do at least a magazine piece on him.

Dylan was a very hidden character. No one really knew who Bob Dylan was, so I handled him in a very straight biographical manner. Dylan reviewed a work-in-progress manuscript of [Bob Dylan: A Biography], and interviewed. “You’ve done a good book on me. I want to make it even better.” He later said, “I like the book. That’s the weird thing about it.”

I write with a lot of compassion for Bob Dylan. I respect him as a person and an artist. The people surrounding Dylan always felt that he was a very fragile person. It was as if he had to be protected. It wasn’t until a few years later that Joan Baez and Dave Van Ronk would talk freely and honestly about him. Dylan only wanted to be the next Elvis. There was this intense pain that forced him to write certain things that came out of the air. A poet feels his own persona, his place in the world, and the screwed-up condition in that world.

Jagger and the people around him, know that he is a very straight cat who is making a million bucks playing the role of a pop idol, getting into it more heavily than he should. There’s never the feeling Mick must be protected. People opened up a great deal more about Jagger than they did about Dylan.

The Dylan women (Joan Baez, Suze Rotolo) have that intense feeling that he was, and still is, someone special. Dylan’s women are still in love with him, although on a different level than it originally was.

Jagger to a large extent is career and business oriented. He’s a businessman who’s still at the London School of Economics. Dylan on the other hand, is a human being, while Jagger is a personality. The big difference is that Jagger had grown up in a very stratified social setting, where authority is very important, and where aristocracy still means something. Jagger quite naturally, was caught up in that kind of thing: school was important, your parents’ wishes are still important, etc. Dylan never was.

If you are going to get into a superstar level, you have got to be hard. In the beginning, Dylan had the bodyguards, the Albert Grossmans. Jagger has the ability to build a wall around himself. You’re an idol, and it’s the kind of thing they put you on the crucifix for. You have to be hard and be protected, or it’s going to destroy you.

Jagger was still very much concerned with what happened at Altamont, and he wanted to avoid any similar incident. Therefore the ’72 tour was highly choreographed. In this way, he hoped to maintain greater control of the kids. The whole atmosphere seemed very much contrived.

As far as the Dylan 1974 tour there was much more of a sense of genuine excitement. Some of the songs took on a jazzy effect, with The Band bouncing behind Dylan. There were a lot of kids from the ages 12-18 that were really into “Maggie’s Farm.” The early protest songs that turned us on in the early sixties, were once again gaining a sense of purpose and sting. Dylan was freely interpreting his old songs with a renewed interest that seemed hard to believe. The feeling was very Blonde On Blonde, that sense that he was just about to step past the edge of insanity. He was trying to drive home that 1966 atmosphere that was so magical, and he did it with remarkable ease.

Kenneth Kubernik: There is another American original, a musician whose body of work, scope of influence, and inscrutable personality mirrors so many of Bob Dylan’s most singular attributes. Pianist Keith Jarrett is not a name that leaps to mind when talkin’ ’bout Bob’s imperishable impact, that litany of artists long identified with his idiosyncratic approach to song craft, interpretive wanderlust, and rousing conviction.

There is nary a one that reeks of jazz. But Jarrett – revered by players and serious students of improvisation, reviled by the jazz constabulary for his irascible nature – has, since the ’60s, spun closely within Dylan’s musical orbit. When jazz was moving uncomfortably towards rock and funk, Jarrett had his trio perform “My Back “Pages,” and “Lay Lady Lay,” coping a Floyd Cramer groove more redolent of Nashville’s skyline than Manhattan’s hot house revelries.

In an interview with England’s Melody Maker, Jarrett cited Dylan’s insight that artists “walk a razor’s edge,” when asked to describe the opaque process behind his mesmeric solo piano recitals. More than Monk and Miles, Trane and Bird, Jarrett found common cause with Dylan’s redoubtable independence of thought and action. It is amusingly apt that Dylan, in recent years, has turned to performing the American songbook – “standards” – that provide the beating heart of every educated jazz musician. He’s on Jarrett’s turf here and one can only imagine that aching croak nestled inside the pianist’s ineffable accompaniment. Wonder boys…”

Outside of maybe Bob Marley and Jimi Hendrix, no popular musician commands a more robust, enthusiastic international following than Dylan. His “voice” is heard in every language that speaks through music to celebrate the resiliency of the soul against the tides of a world gone wrong.

Bill Carruthers: My father William (“Byl”) Carruthers conceived and developed the premiere season of The Johnny Cash Show. Stan Jacobson, was the series’ producer, with Joel Stein as the associate producer. My dad previously directed TV shows for Soupy Sales in Detroit, and Ernie Kovacs, and The Dating Game for ABC-TV.

My dad was the executive producer and director for the first year. It was his show. The Johnny Cash Show debuted on June 7, 1969. Cast and crew taped the programs at Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium, home to the Grand Ole Opry from 1943 to 1974. Bill Walker was the musical director and arranger. June Carter Cash and the Carter Family, Carl Perkins, the Statler Brothers, and the Tennessee Three were screen regulars.

The first show was a mindblower, as we all know [with guests Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, and Doug Kershaw], and the first season surprised ABC enough to pick it up. The sets were cheap, ’cause they had no money. The production issues they faced retrofitting the Ryman Auditorium were immense.

For that year of pre-production and production, my dad and John were close. He showered my dad with gifts, among them a 1932 Martin Guitar and a Civil War Colt pistol. John had a pair of [Colts] with consecutive numbers. He gave my father one and he kept one, so they’d each have one as a symbol of their relationship.

Dylan called my dad before he and his staff left for Nashville. I had gone to work with my dad that day. He had an overall deal with Screen Gems and had an office on their lot. He had said we were going to get lunch, and then his assistant beckoned him back to the office, saying it was important.

Two full hours went by, and I had to wait. When he got off the phone, he came out and said that he had just gotten off the phone with Bob Dylan. I asked him what he was calling about. He said that Johnny wanted Dylan to do the show. Johnny really wanted Bob to do the first episode and told Bob that he would be in good hands with my dad, and he wouldn’t have to do anything he didn’t want to. My dad said Bob was “feeling him out” on the phone.

My dad was very cool about letting me hang when the musicians were there, and yes, I got to fetch coffee and stuff for Bob Dylan, in the hour or so before the taping.

I distinctly remember Dylan having two very sedate western-style two-piece suits laid out, and him saying to my dad, “Byl, which one of these do you think would be best?” A few minutes later, my dad said to the assistant director, “I can’t believe Bob asked me what he should wear!”

Dylan performed three songs from Nashville Skyline on the first episode taping on May 1st and then broadcast on June 7, 1969: “I Threw it All Away,” “Livin’ the Blues,” and, as a duet with Cash, “Girl from the North Country.”

Chris Darrow: In 1964 I had just gotten married and it was great to have a steady paying gig with the bluegrass group the Dry City Scat Band. During this period Richard Greene brought in a friend of his who was working with the Chad Mitchell Trio and had just returned from England. I had never seen a guy in Beatle boots and long hair before and he was raving about the scene in the British Isles. He was wearing small dark glasses, his name-Jim McGuinn.

Later in that summer the Scat Band was playing at the Ash Grove and I ran into Chris Hillman, whose group the Scottsville Squirrel Barkers had taken our place at Disneyland. They were a band that also spawned Larry Murray on dobro and later on, Bernie Leadon on banjo. By this time, however, Chris Hillman was playing in a group that later was dubbed the Hillmen with Vern and Rex Gosdin and Don Parmley on banjo.

On the way to the stage I asked him what was cookin’ and he sheepishly said, “I joined a rock and roll band. I need the money. They’re called the Byrds.”

In those days, the hard-core bluegrass guys didn’t talk or think about rock and roll. But the times were a changin’ and the Beatles hit hard, especially the folk scene. Bob Dylan and Joan Baez were the scene-stealers and groups like the Kweskin Jug Band, the Greenbrier Boys and the Charles River Valley Boys were the East Coast favorites.

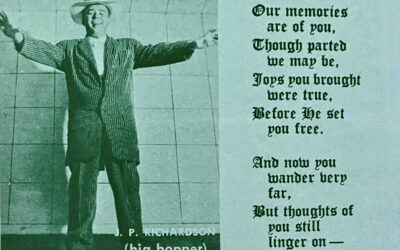

As the British Invasion happened, most of us saw the need to jump in; Rock and Roll was back. Most of us had turned away from rock and roll because most of our heroes were dead (Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, Eddie Cochran, Sam Cooke, etc.) or were in jail or in trouble (Chuck Berry-Mann Act violation and Jerry Lee married his cousin). Little Richard was great but he was just too weird and Elvis joined the Army and got into movies.

So, we were left with Bobby Rydell, Bobby Vee, Fabian and Frankie Avalon.

The folk boom filled the musical gap for most of us and now the Beatles were bringing our own music back to us and it was familiar. Almost instantly, most of us bluegrass guys got into some sort of electric outfit and tried to do it.

After the English Invasion, I started a group called the Floggs, an all-electric band in the Yardbirds, Them, Animals, Stones mold. I was the writer, lead singer and became the bass player by default. We were guitar, bass, organ and drums.

We did gigs with the Rising Sons, with Ry Cooder and Taj Mahal, who were friends from the Ash Grove scene. We were very good and recorded a 7-song demo to shop. Most of the songs were original except for “Hesitation Blues,” and Dylan’s “Walkin’ Down the Line.” Some of my tunes I brought into the formation of the Kaleidoscope.

My wife and I were sitting watching TV one night in May 1965 and we turned on the Hullabaloo TV show. It was great program and we all waited for it because there was little rock and roll on TV.

All of a sudden there was a sound that permeated the airwaves, a jangly twelve string guitar lick and a close up of a guy in small dark glasses and a Beatle haircut. I said, “It’s that guy that Richard Greene brought to our gig.” As the camera panned the band, I caught a glimpse of another familiar face, Chris Hillman, but instead of his short curly hair and Levis and T-shirts, he was wearing Beatle boots, pegged pants and had a long, straight, bobbed haircut. “This is Chris’s new band, I guess,” I said to Donna.

It was the introduction of “Mr. Tambourine Man” and it was, of course, the Byrds. Now there were people who we knew who were in big bands and it looked like something we could all do.

Kim Fowley: Dylan was pioneering everything. So of course, he would be at the forefront because that’s his job to be first.

Dylan played the UCLA Folk Festival in 1963.

In 1965, Billy James invited me to a reception in Hollywood for Bob Dylan at Columbia Records. I said to Dylan, “What’s your gimmick? What’s your schtick?” And he replied, “Asking questions and telling stories.”

Then the following night, Bryan MacLean, a Byrds’ roadie, before he was in Love, and I, were standing in front of Ciro’s. We knew there was a party in Hollywood at Ben Shapiro’s house who was Dylan’s booking agent. It was behind the Continental Hyatt House. We decided to crash it.

So, we jumped over a fence and climbed in through the kitchen window. I had a problem getting over the stove, and a pair of hands grabbed me across the stove-and it was Bob Dylan! And he grabbed Bryan and helped him through the window. He then asked if we wanted something to eat. “Sure, man!”

He wasn’t happy with the other people in the room at his party. “You guys wanna come? Hey, you’re that guy from yesterday! Have some chicken.” And he went and got us plates in the kitchen and fed both of us. He was very kind.

Then there was another party across the street. I was with Danny Hutton, later to form Three Dog Night. We followed Dylan’s entourage and ended up in a room at a hotel apartment. People then started harassing him. “Sing for us or we’ll kick your ass!” They were being mean. I felt bad for Bob Dylan.

So, I immediately jumped up and said, “Fuck all of you. I’m better than he is and I also sing better in his voice! So, you, Bob Dylan, play me Bob Dylan chords!”

On some level I got him off the hook. He said, “What do you wanna sing?” And I asked, “I dunno, what have you got?” Dylan said, “Sing something about walls.” Dylan picked up an acoustic guitar and I made up a song on the spot. The audience was shocked. They had no idea what to do. They didn’t want to applaud or fight. They were really confused.

Dylan encouraged me to be a solo recording artist. As Dylan was being whisked away by handlers, he offered some wine and said, “You’re as good as I am.”

Roy Silver was my manager in 1966, who in 1962 was the original co-manager of Bob Dylan with Albert Grossman.

I like Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid. The Dylan songs and the atmosphere. I like Bob on-screen. He has this charisma in the sense that he holds something back, and you want him to put out, and you anticipate, and he lets you see a little more. He teases you. The Charlie Chaplin mannerisms. You hear him and he stops singing, and you go ‘Wow.”

Rodney Bingenheimer: I met Bob Dylan in 1965 at The Trip nightclub on the Sunset Strip in Hollywood. At the club I was with Billy Hinsche of Dino, Desi and Billy, who took a photo of Dylan and I holding my camera.

I went to the amazing December 1965 Bob Dylan concert at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium. Marlon Brando sat in front of me. After the show, which was on my birthday, we all got up from our seats and went backstage. It was all happening! I love Cher singing Dylan’s “All I Really Want to Do.”

Andrew Solt: 1965 was the year my life changed. I graduated from Hollywood High School, started college at UCLA in February ‘65, and I discovered the Byrds at Ciro’s on the Sunset Strip. Ciro’s was two blocks from where I lived. Mecca! Dancing to the Byrds’ jet-powered rock at Ciro’s on Sunset Strip had me feeling like I was present at America’s version of the Cavern in Liverpool.

One day late that fall I heard on the AM radio, probably KFWB or KRLA, that Bob Dylan would be appearing one weekend at three L.A. area venues. My brother John and I bought tickets his concerts at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium, the Long Beach Municipal Auditorium and the Pasadena Civic Auditorium.

The first set was acoustic. But when Dylan strutted out after intermission with the Hawks, the world seemed to stop spinning for a couple of hours. I was even more transfixed by Dylan live on stage with his electric guitar.

I was thrilled by his every move, his delivery and the way he cocked his head and sidled up to the microphone. His confidence and charisma were undeniable. He may have been an unlikely rock icon, but he definitely was one. It couldn’t have been any better. It was transformative. I was immersed in something groundbreaking that felt raw as vibrant as Dylan and his group were taking the audience and rock ‘n’ roll on a magic carpet ride to a whole new level. I didn’t want those nights to ever end. It was undoubtedly one of the most exciting weekends of my early life.

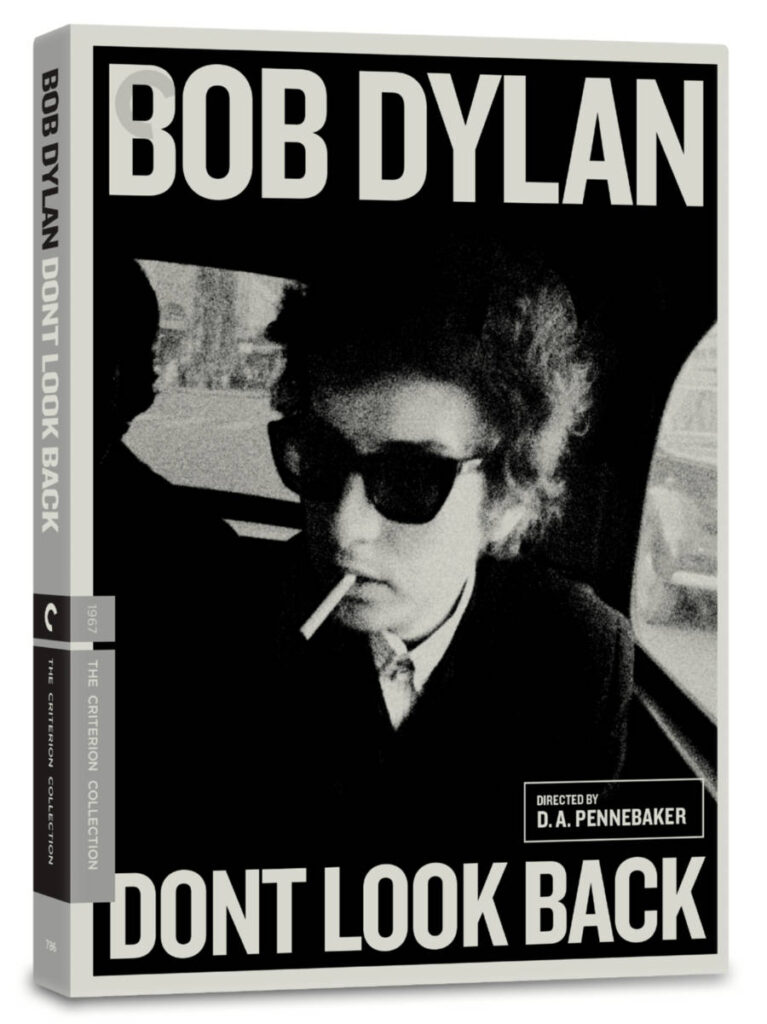

In May 1967 when Dont Look Back the D.A. Pennebaker documentary on Dylan’s UK tour in 1965 premiered in Los Angeles at an art house in Los Angeles, the Los Feliz Theater, I was there. Transfixed. Dylan on screen. Not stage. Docu verite’ window into a magical world-spellbinding moments, musical gems, beyond comprehension. Next day. Same place. Back in line for another shot.

Paul Body: Bob Dylan at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium. Saturday, December 18, 1965.

Joe, Evelyn and I went to see Bob Dylan tonight. He was too much. He came out dressed in a brown and black houndstooth suit, all by himself. With just his guitar and harmonica, strapped around his neck. His skin looked like the color of sour milk and I have never seen anyone so skinny before. Evelyn was really digging it. I was so glad. He ended the first part of his show with a song called “Desolation Row.” It was really BEAUTIFUL. I haven’t any idea what it is about. His songs are hard to pin down because they mean so many different things. There is a line in “Desolation Row” that reminded me of Sioux Cameron, that line about putting her hands in her back pockets, Bette Davis style. When he got through you could hear a pin drop.

Then there was an intermission and then he came back on with a group, about 5 guys. The organ player really cracked me up because he had this giant forehead, matters of fact they were all silly looking, the piano players nose looked like a parrot’s beak and they were all dressed in black, they looked like a bunch of Southern preachers. They started off with a song about Juarez, Mexico and once they started the weirdest thing started to happen, people started getting up and leaving. They were offended by the guitar and drums. What a bunch of chums because Dylan was rocking. There were these two guys who really stood out because they were sitting in front of me, one of the guys was tall and skinny and he looked like a jealous bird. He looked really grim. The other guy wore glasses too but he looked like he was just following. How could they walk out like that?

Meanwhile up the stage, Dylan was moving around like he was plugged into a high-tension wire. BUZZ BUZZ BUZZ. The last song he did was “Like A Rolling Stone,” he kept shouting the words, “How Does it Feel?” over and over and then he left. Him and his Southern preachers. I was moved. Evelyn was moved too. As we were going out, we ran into Greg Moore, Sioux Cameron, her sister, Cathy, Karen West, Gooler and Priscilla, we also ran into Harry Speer who had walked out. Everyone dug it except Harry. Everyone was going to smoke some pot, hell that stuff Dylan was singing about got me high enough.

Mike Bloomfield was the original guitar hero even before Clapton at least in my hood. I don’t how we knew about him but we did. Maybe it was “Like A Rolling Stone” but mostly it was the guitar strangling on the first Butterfield album. He was a true character, just check out his bit in the movie Festival! Saw him at the Monterey International Pop Festival with Electric Flag right after he split from Butterfield, lots of horns and Buddy Miles and it was just as advertised American Music. Got to see him up close back stage at the Shrine in L.A. He was jamming with Jimi Hendrix. I heard that before I got there that when Bloomfield showed up and Jimi started playing Bloomfield’s licks that is how heavy he was. Anyway in 1968, he could make that Les Paul and do everything but crawl on its belly like a reptile.

Tom Law: I grew up in Hollywood and worked in the movies as an extra. We rented the house I grew up in to Odetta. I was then on the road working for Albert Grossman and with Peter, Paul and Mary and bringing 150 grand a week to the office and making $200.00 a week. That was good money in those days. That was cool. Albert offered me a job to go with Bob Dylan and road manage him.

I later lived with my wife Lisa at The Castle in Los Feliz, a nine bedroom and nine bedroom major house. It was a four-acre place. Mike Bloomfield lived at The Castle and do did Electric Flag, Paul Butterfield and the Blues Band, Nico, Andy Warhol and the Velvet Underground.

Bob and I had a nice relationship there when he was living at The Castle. Late 1965, ’66. Blonde On Blonde. I knew him back in ’62 when I was working at The Village Gate and he had just come to town, and up at Albert’s a lot.

Lisa and I saw Otis Redding at the Whisky in 1966 and it was totally mind blowing. To see a man get so into it. I didn’t know from Otis Redding. Bob said, “Come on, we gotta go see this guy!” “All right.” And, man, when I saw him, he was a transforming guy.

.

Carlos Santana: FM radio in 1967 and ‘68. KMPX, KSAN. It blew my mind when I found it. Here’s the word: Consciousness revolution. It did not come from Liverpool or New York. I think it came from San Francisco. The psychedelic shock. Haight-Ashbury. When I first heard “Desolation Row,” it was like, “Man, this is like being inside one of Bob Dylan’s songs or something.”

For me, being right out of high school, and listening, really listening, it gave me a vast awareness of “where do I belong it all this?” And I looked at B.B. King on my left and Tito Puente on my right. The first time I saw Michael [Bloomfield] play guitar…it literally changed my life enough for me to say, “this is what I want to do for the rest of my life.”

Greil Marcus: The first thing a friend said when we first heard the album John Wesley Harding on the radio, late one night on KSAN-FM, “I think we’ll be listening to this for a long time.”

Michael Simmons: I adored John Wesley Harding when it came out at the end of ’67. Still do. It’s one of my favorites among many Dylan favorites. There’s an account that I read years after the album was released that Dylan had a huge, well-thumbed Bible on a stand at his home in Woodstock. I remember thinking that’s where John Wesley Harding came from to some degree. It’s full of morality tales and parables and Book Of Revelations dread. One could argue that JWH is Dylan’s first biblical album. Also, Bob obviously knew that the album would be pored over by fans looking for ‘the truth’ and the liner notes are hysterically funny — a dig at First Decade Dylanologists. The country seduction tunes “Down Along the Cove” and “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight” end the album and seamlessly lead into his next – Nashville Skyline.

Ritchie Yorke. John Wesley Harding was of particular interest to me. I was living and writing in Toronto in 1967 and was close to Ronnie Hawkins’ camp. I would subsequently arrange for John and Yoko Lennon to stay at Ronnie’s place when they came to Canada in late 1969 to announce the Peace Festival and meet with Marshall McLuhan and Prime Minister Trudeau, the birth of political pop. Since JWH was Bob Dylan’s first album post his transformation into an electric artist with the assist of former members of Hawkins’ backing group, the Hawks (by then branding themselves as the Band), it was of particular interest. It was a big surprise to hear Bob wandering into the Christian landscape, at a time when many other artists were rejecting old school religion and branding it as a prime cause of injustice and racial discrimination. Bob would of course return to these controversial shores with his Slow Train Coming and Saved projects. JWH was a great setup for what would arguably become his most commercial album effort, Nashville Skyline. Short songs, skillfully played and delicately delivered.”

Richard Williams: Eighteen months was a lifetime in the late ’60s, and John Wesley Harding ended the longest, loudest silence in the history of rock & roll. No one knew what Dylan was up to. No one knew the truth about his “retirement”: were the unconfirmed rumors of a motorcycle crash simply a cover for the time needed to free himself from advanced chemical dependencies?

“I Pity the Poor Immigrant,” “I Dreamed I Saw St Augustine” and “All Along the Watchtower” forced us all into a radical reconsideration. The album was a blast of clean air—not just for us, but for Dylan, too. And it still sounds pristine.

In 2009 Bob Dylan released his 33rd studio album. It was called Together Through Life. I love that title because it describes how I feel about him. We’re not related, so he’s not my brother. I’ve never met him, so he’s not my friend. I wouldn’t burden him with the role of prophet, priest, shaman or griot. But he’s been with me since the summer of 1963, when I first heard The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, his second album, then hot off the presses. I was 16 and he was 22. That’s a long time ago. Sometimes it feels like it (time passes slowly up here in the daylight) and sometimes it doesn’t (time is a jet plane, it moves too fast). So, I’m me, and he’s Bob Dylan. Together through life.

David Kessel: During 1976, my brother Dan and I were session guitarists and very involved on the Phil Spector-produced sessions for Leonard Cohen’s Death of a Ladies Man album at Gold Star Recording Studios in Hollywood.

I really got a kick when Dylan walked into the studio with his arms around two broads, and he was holding a bottle of Scotch in his right hand, kind of a Frank or Dino type deal. Phil brought Bob to us and made the formal introduction.

I really liked seeing Phil and Bob standing together. I knew he went way back with Phil, who was smiling and they both were very comfortable in the hang near the echo chamber.

Dylan asked me, “so what do you do?” Phil quickly answered, “Mr. Kessel, please tell Mr. Dylan what you do for me.” I said, “I do whatever needs to be done.”

Dylan took it all in and looked directly at me, “Whoa… Whatever needs to be done!” And he stretched the words like it was a lead vocal from “Highway 61 Revisited.”

Roger Steffens: It was the unnerving quality of his initial albums on Columbia Records that helped make emergent “twenty somethings” aware that you could go beyond pure vocal harmonies and love sick teenage messages into a totally different iteration of popular music. It was other college kids that turned me onto him, and at first, I didn’t get him. I was an Alan Freed doo-wop rock ‘n’ roller all the way through. And the only other vocalists I listened too were Nina Simone and Harry Belafonte.

It’s fascinating watching Dylan bring his unreleased music and catalog forward, because Dylan is more than an advanced amateur historian. Dylan is a folklorist of the first water. Dylan in mono, like anyone else documented in the mono setting, has to have their sound all properly balanced at the same time. This situation helped create immortal masterpieces of one take art, like Jackie Wilson’s “Lonely Teardrops” – one take, live, in a big empty theater, with everyone fully engaged.

Dr. James Cushing: Dylan’s The Bootleg Series Vol. 9: The Witmark Demos: 1962–1964 are revealing in the way Van Gogh’s sketchbooks are revealing, and the rate of this young man’s productivity was another amazing element of his early success. They are a preview and also the recordings were also done not really to function as recordings but to function as demonstrations or as examples of how the song could sound. Which is to say that the kind of self-consciousness that can come into a recording situation in a studio with an engineer is probably not going on here. Given that it’s just one guy and a reel-to-reel tape recorder in some six by eight foot office studio on Madison Ave.

These early Witmark demos also demonstrate that Dylan learned and absorbed much in Hibbing, Minnesota, before he relocated and re-invented himself in New York. On its own terms, the mono Dylan bestows a single-sound-source structure on the music that fits the three “rock” albums very well.

The mono does give that single sound source and that evenly blended sound that adds to the mysterious of it. Whereas the stereo mix somewhat separates the instruments and add an additional clarity. Which is not always exactly what you want. I think some of the early Beatles’ records are terrible in stereo and much better in mono. The stereo mixes, when I first heard them, added separation-definition to the instruments, so that I heard the two guitars and the upright bass in “Desolation Row” clearly — but is clarity the most valued goal with music that creates/inhabits a surrealist dreamscape? Also, other minor details are different, such as “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry” being 40 seconds shorter in mono, or the lead guitar on “Visions of Johanna” coming in at different places.

The first time I ever felt absolutely thrilled by a piece of music – thrilled in that way that includes physical fright, even to the point of trembling – I was twelve years old and Michael Bloomfield’s guitar was responsible.

After each chorus of “Tombstone Blues” on Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited, a sound as snarling and heedless and courageous as anything I could imagine leapt out of the speaker and implied a whole world where adult men and women fought hard for their lives and died anyway. Not just implied it – proved it. And what thrilled and scared me was the way the music showed me that, even as a boy, I lived in this world, and had to affirm it to survive in it. I had no idea how I was going to affirm it. I only knew that every record this Michael Bloomfield guy played on was potentially a piece of this thrilling wisdom.

I saw Dont Look Back in a North Hollywood theatre when it opened, in May 1967.

We must remember that, as far as I or anyone in my circle knew, Bob Dylan’s June 1966 motorcycle accident had left him either 1) dead, or 2) so permanently disfigured that he would never tour or record again.

Like the Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits LP released that same season, Pennebaker’s movie functioned within the context of the star’s disappearance; this movie was as close as you were ever going to get to seeing this brilliant-but-now-vanished legend in concert… And the movie kept functioning that way until early 1974, when the legend returned to the boards…

The movie’s still astonishing, even if one’s seen it a hundred times. I show it on DVD to students and they identify with the young genius right away.

When I watch the DVD myself, I’m always struck by Dylan’s youth and self-confidence, and by the permanent power of these songs as evocative works of art. That Pennebaker included the non-Dylan scene with Albert Grossman and Tito Burns in the office is a tribute to his courage and sense of realism. (Has there ever been a similar scene in any music documentary?)

Having no friends to accompany me, I saw it with my very conservative father (born 1920, Marine Corps in WW2), who detested everything about it; his main comment, as I recall, was that “the whole movie was close ups of a bunch of really ugly-looking people!”

That remark encapsulates the period’s “generation gap” as well as anything I can remember. In terms of blending concert footage with behind-the-scenes intimacy, it remains the best rockumentary movie ever.

John Wesley Harding works together sequentially so well the same way that the songs of Sgt. Pepper work so well together, not in terms in terms of creating a narrative, but in a sense of all adding up to a certain collective statement. A certain description of a mental, emotional and intuitive place in the mind that is both new and old. This album is timeless.

Did Jimi Hendrix ever “understand” the words to “All Around the Watchtower?” He messes them up on the studio LP and on every live performance I’ve heard. No matter — he re-conceived the song as a dramatic piece for guitar orchestra, acoustic/electric, and how many overdubs??? Jimi Hendrix offers fullness of detail where Bob Dylan offers mere suggestions. Hendrix’s “Drifter’s’ Escape” is essentially the same idea w/out the newness.

Dylan himself acknowledged Hendrix’ version of “Watchtower” on his scorching version (with The Band) from 1975’s Before the Flood. When Dylan does it the voice and the narrative in their simplest sense are front and center. When Hendrix does it the vocal part is only one section of a larger essentially orchestral conception involving different guitar sounds, dynamics, Hendrix is really orchestrating it. In concert now Dylan sort of does the number as a tribute to Hendrix.

When we think of Bob Dylan geographically, our first associations are with Hibbing, in the Mesabi Iron range of northern Minnesota, then Greenwich Village around 4th Street, then upstate New York.

But the truth is, Los Angeles has been Dylan’s primary residence since 1973, and the city has played a substantial role in Dylan’s life and career. How appropriate that the man who wrote “he not busy been born is busy dying,” having made enough money to live anywhere he wants, has made his home in the city of radical self-invention.

Dylan is a genius and we are fortunate to be able to share the same time and space with him. Geniuses do that. Geniuses continue to grow and develop. Geniuses have different periods in their art. Geniuses continue to have work that resonates with people. And Bob Dylan is the one genius to have come out of American rock music. And there are no others, except possibly for Jimi Hendrix. But he died too young for us to really tell.

The Basement Tapes, a Dylan and Band (a.k.a. Hawks, Crackers) collaboration recorded June-November 1967, were wholly concealed from public viewing hearing in ’67.

The Basement Tapes Complete are like a whole shadowy subterranean alternative career for Bob Dylan. It’s as though somebody discovered that while James Joyce was writing Ulysses and Finnegans Wake, he also wrote two other novels that were completely finished but put them in a trunk.

We all know Dylan was in some sort of holding pattern in the last part of 1966 and into 1967. And an acetate of 14 songs were distributed to some publishing companies in the UK. Some of the covers, including the ones that charted, Peter, Paul and Mary, Manfred Mann, continued the policy of his songwriting and publishing copyrights being covered earlier by the Turtles and the Byrds. And the work Artie Mogull did with Grossman getting those tunes out to producers and record labels that caused radio exposure and record sales. The Peter, Paul & Mary recording was a very simple matter because it was their sound equipment that they had borrowed in the basement. It was PP&M’s mixing deck and tape recorder and microphones. Booms and everything. So, as a way of repaying them for the three-month use of their shit, Dylan said “OK Peter, Noel and Mary. You get first dibs on the songs.” So, they did “Too Much of Nothing” which became a hit. And those other songs became hits for a number of other reasons. But I think a big part of it from what I remember was these tunes were new “Dylan songs.” And this was kind of as close as we were going to get to a new Dylan song for a while.

There’s clear evidence that Dylan never intended The Basement Tapes to be commercially released.

I would connect it with the John Coltrane Quintet Live In Japan. The group with Alice Coltrane and Pharoah Sanders and Rashid Ali. Alice Coltrane confirmed that no one in the band knew that those concerts were being recorded. Because of language and translation difficulties they did not understand that a safety tape was being made of it. So, they didn’t know they were being recorded. And, as a result, there’s a freedom there like nothing else in his records. “My Favorite Things” is 57 minutes. So, they know they are being recorded but they know their recordings are private, secret, just for them. Then an album comes out 7 years later.

The new Basement Tapes collection to some ears might have begun with an exposure to a bootleg album or cover versions of the songs now housed in this multi-disc set. And now, Dylan, issues the package under his Bootleg Series Vol. 11. Where retail product is part of the marketing and label identity. And not a posthumous release. It’s a kind of magical, sacred object, actually. I have to sort of be careful with it. Dylan and The Band commands our attention on this album in a wonderfully paradoxically way which is by completely ignoring us. And by focusing on all of the tributaries of American music and the wonderfully surreal braiding of those tributaries in Dylan’s own mind.

Kirk Silsbee: After the July 29, 1966 motorcycle accident, Dylan was off the public radar for what seemed like a couple of years. We didn’t know it but he was holed up in Woodstock, which most of us had never heard of before the festival. That absence gave way to all kinds of speculation on his whereabouts and well-being. Though he wasn’t speaking for himself, Dylan had several interlocutors in the form of his songs, performed by others on the emerging FM rock radio. Peter, Paul & Mary introduced “Too Much of Nothing,” the Byrds gave us “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere,” “This Wheel’s on Fire” was done by Julie Driscoll with Brian Auger & the Trinity, and Manfred Mann did “Mighty Quinn.”

The songs were all introduced to us by those artists, and it was a form of mental sport to try to divine some kind of secret code being sent to us from Dylan through them. I imagined him in the same kind of cloistered bunker that Thelonious Monk stared out from on the cover of his classic Underground album of 1967, furtively sending cryptic messages to the front any way that he could.

Daniel Weizmann: The only thing I can compare John Wesley Harding to in 20th century pop is David Bowie’s Berlin trilogy.

In both cases, a leader of the zeitgeist dared to shake off their own mythological persona and “humanize.” And in both cases the gesture was so uncynical and urgently felt by the artist that what they created didn’t just add a dimension, it made us understand better what they had been saying all along.

Much has been made, of course, over Dylan going electric two or three years earlier, it’s become a kind of trope for “Entering our modern era”–compared freely to Picasso’s cubism and other modernist rebel cultural plays.

But to me John Wesley Harding was the greater actual rebellion: Here’s Dylan choosing to swim not just against the original folk culture that spawned him but against the counter-culture that he spawned, against the very grandiosity that was holding him in place. One thing is for sure — six months after Sgt. Pepper’s. the flowering of volume in rock music, and the summer of media-saturated love — Dylan took a stand against the electric swarm.

His interest in the Bible at the time also seems to reflect a desire to put into place some higher power that might release him from the absurd trappings of modernism and his own unasked-for Exalted Modern Potentate position. Songs like “I Pity the Poor Immigrant,” “Dear Landlord,” and “I am a Lonesome Hobo” don’t just talk straight, they don’t just roll back the psychedelic chaos of an earlier style, they also stare down a former glamor…they critique a straying-from-the-source.

Everything Dylan did before this album was Amazing with a capital A. But on John Wesley Harding, he was like the Wizard of Oz, pulling back the curtain to reveal a different kind of amazing, altogether more miraculous, pathos at the Speed of Life.

In the same way, Dylan always had the romantic country balladeer in him, long before Nashville Skyline. You sort of knew that, listening to songs like “Boots of Spanish Leather” or “Love Minus Zero.” But you didn’t expect him to open the newest LP by skating out on a duet with Johnny Cash! Or to croon the heart wrenching simplicity of “I Threw it All Away” or “Lay Lady Lay” without even a hint of the pared down psychedelia of John Wesley Harding.

The intensity of Dylan’s artistry is such that, when he embodies himself, he goes for the total person.

I still can hardly believe Nashville came out in early ’69, that rickety, bruising rollercoaster of a year. Dylan’s bravery in making this record at that time is also jarring. With the onslaught of ferocious modernism, orgiastic liberation, and cultural rancor, he tips his hat with a friendly smile and graciously asks for a ride to the country and to the human heart.

It’s no accident that Dylan ultimately settled in Los Angeles to the degree that he ever settled anywhere.

As a cowboy-pioneer of language crossing the American landscape, he knew that the Pacific is the end of the line. You haven’t completed the journey until you’ve arrived. Also, Dylan has always had showbiz in the blood–he’s a cinematic song and dance man and classic Hollywood iconography is always showing up in his work. For our greatest songwriter, L.A. is adversary, inspiration, hideaway, and shoreline.

What is it about Bob Dylan that gives a certain sort of person permission to speak? Is it the spinning, kaleidoscopic verbal energy that distinguishes his finest songs? Is it the throng of traditional voices from an older America that can be heard resonating in those songs? Is it the sheer bulk of his legacy – forty-six albums in forty-three years, 1600+ concerts since 1988 – that calls for response in the form of hefty volumes? Or is it the way his untrained voice, startling imagery and charismatic animal presence encourage his listeners to discover and enact their own uniqueness?

Dylan is the last man standing from the sixties rock revolution, the only dignified superstar. While the Stones, McCartney, the Half-Who and Clapton harden into sclerotic irrelevance, Dylan, continues creating vigorous, compelling new work, shaped by folk and blues traditions and flawed not by formula but by risk – Time Out of Mind in 1997, Love & Theft in 2001, Masked & Anonymous in 2003, and the first installment of three promised volumes of autobiographical Chronicles in 2004.

By now, no one can give accurate measure of Dylan’s influence on sixty years of singer-songwriters who discovered their own voices through hearing his. But as the shelf of books about Dylan grows into a wall, a reader might find some measure of those books useful. If the recent spate of Dylan-related books is a fair sampling of what his critics, commentators and chroniclers have discovered in his music, it seems they still have much to learn from his example.

Bob Dylan has, over the course of a nearly 63-year career, become something more than a music icon, visionary, or “the voice of a generation.” He speaks to us through that ineffable marriage of words and music, suffused with the rarest emotional candor, compassion and empathy. Yet he remains an impenetrable, enigmatic figure.

It is this very paradoxical character that entices generations of fans. His legions dote on particular periods – ‘60s only, thank you, or circle back to Blood On the Tracks as their North Star – while others drift in and out, depending on the particular travails of their own lives. Dylan is there to console in the dark of night, to provide succor at the dawn of a new morning.

It’s only of marginal importance that he’s had X number of hits, sold Y number of records, or that digital platforms have recorded Z number of streams, downloads, etc. The one irreducible fact is that Dylan, like Gershwin, Ellington, Aretha, and maybe one or two others, has come to define an essential American character, an exceptionalism that Whitman described as containing multitudes.

One of the greatest things about Dylan’s artistic personality is the way he turns it like a Rubik’s Cube, turns it and turns it and–voila!–some new aspect that was secretly there all along suddenly gets a full face in a way that throws the listener for a loop. For instance, Dylan was always a rock and roller, long before he went electric. Of course he was. That’s what made the Newport plug-in move so disarming–it exposed the unobservant and forced them to acknowledge that he wasn’t breaking away from anything. Quite the opposite: he was digging down deeper into his essence.

Of course, there’s really no way for film to catch the kind of wizardry that happens between Dylan and the English language. His gifts are supernatural, invisible to the naked eye. He also famously refused to be photographed while writing because he considers it a private act. Fair enough.

Still, there’s a clip that Pennebaker shot in 1966 for Eat the Document which appears in Martin Scorsese’s No Direction Home where we actually get to watch Dylan create in real-time, on the fly, and it’s one of the most astounding things you’ll ever dig. In a fast minute and fourteen seconds, you are zapped with the mental turbulence and psychedelic hopscotching of a great poet at the zenith of his powers.

In the clip, a bedraggled, tour-weary Dylan is accompanied by Richard Manuel. At a glance, it’s just a little bit of stony afternoon humor, but this crazed little minute pulls back the curtain to let us see the running gears of the same mind that created “Gates of Eden” and “Mr. Tambourine Man” and all those other labyrinthine lyrics. He stands in (or should I say fearlessly withstands) a zone of verbal chaos that skirts word salad and turns up surprise juxtapositions, deep hidden meanings, and urgent paradoxes the way an eerily confident blackjack dealer might splay, shuffle, and deal the deck without ever looking at his hands.

Seymour Cassel: I could always get into the Whisky A Go Go because Elmer Valentine and Mario Maglieri at the door took care of me. When I was working with [John] Cassavetes, we gave Elmer a piece of the film Faces so we could shoot at the Whisky.

Bob Dylan was a fan of Faces. I knew The Band who worked with Dylan earlier when they played with Ronnie Hawkins. Levon and Rick Danko. Cassavetes, Al Ruban, and I took the Faces movie and showed it free at midnight in three different places. Toronto, Montreal, and New York at the Capitol Theater. Bob had seen it there.

I was in New York, and I get a call from Woodstock, asking me to come up for a Fourth of July weekend. And all Bob wanted to know was how we shot the movie, what kind of cameras did we use.

He had seen Faces and wanted to make a movie. I told him we only had two cameras and we’d shoot with a crew of six and take turns. John financed the whole thing, and that’s what Bob went ahead and did.

Jim Morrison and I would read poetry on Sundays. I saw the Doors at the London Fog and the Whisky A Go Go. Jim had the same commitment to his art that Bob Dylan had.

Chrissie Hynde: Bob Dylan’s “Forever Young” has got such a beautiful lyric. I just love it. He’s the pride of our generation. The song is genius. I’ll tell you another great Dylan album, that was not one of his most popular ones, was Shot of Love. The song, “Lenny Bruce.”

Time Out of Mind. It’s one of his best albums. He just sings magnificently, for a start. They’re just great songs. Bob always writes impeccable songs, but my suspicion is that he’s a little impatient in the studio. On this one, he really stuck it out and got gorgeous vocals. The singing is fantastic. The songs are so well crafted and they just got the great sound for each song. You don’t feel like he just got a band in, wheeled them in and played all the songs and left. Each song is very carefully thought out.

Obviously, that’s a lot in the production and I’m sure that’s Danny Lanois who masterminded that. Jim Keltner is the perfect drummer for any band if you ask me. He’s great with Bob Dylan. Keltner is a genius drummer. I love that guy.

Clem Burke: Dylan was just being himself in Dont Look Back. The whole cinema verite concept. You got the feeling you were a fly on the wall and Pennebaker had access.

The Last Waltz was great. I went to see a screening of it at The New School when it first came out and Martin Scorsese and Robbie Robertson spoke at it.

That is getting back to what I thought music videos should be. There you have great performances captured for prosperity. You have a moment in time that should have been captured. All those artists together in one place. Levon Helm blew my mind.

I liked The Concert for Bangladesh, but no behind the scenes stuff at all just about performance.

Michael Hacker: To most Dylan fans in 1969, country music was the devil’s music, the devil being the conservative majority that still ran things in America, even worse, country music was identified as redneck, read “racist” music. That may not have been true or correct, but it was the perception of a lot of young people in America at that moment. In spite of all this, the album became Dylan’s best seller ever, anchored by the hit single “Lay, Lady, Lay,” which reached number seven on the Billboard Hot 100 chart. On that song, worship must be paid to the late, great drummer Kenny Buttrey, for the insanely creative beat he taps on bongos that kicks the song off and the drumming he does throughout that really holds the song together. It’s a beautiful song with beautiful accompaniment, and it sounded nothing like Dylan ever did before.

Even today, fifty years later, people still get hung up on the voice Dylan used for Nashville Skyline. What I think they’re missing is how evocative and beautiful this voice is, and how it shows Dylan’s amazing control of his vocal instrument.

Steven Van Zandt: I’ve gone through different phases with Bob Dylan. I had an older friend who first played me the folk music stuff of Bob the first three albums. I liked it but didn’t understand the whole poetry thing. I was age 12 and didn’t quite get it. He was interesting, even then.

As a guitar player, I’ve played Dylan’s songs with Bruce [Springsteen] and in top 40 bands earlier. Dylan was an extremely good folk guitarist as far as the folk style he played on his first few albums. Extremely adept at that.

The Byrds introducing him to the world, really, with “Mr. Tambourine Man,” was a major factor. I can’t give them enough credit for that. I don’t know if Bob Dylan would have been accepted at Top 40 radio if it hadn’t been for “Mr. Tambourine Man.” I mean that, Harvey. That gang has been a great service to the world. I was a huge Byrds’ freak. Still am. As you know, they lead you to Bob.

On my Little Steven’s Underground Garage and Outlaw Country [SiriusXM satellite radio] channels I program things from Johnston’s Cash albums all the time, especially the live San Quentin. On my shows I like to spotlight producers, whether it be Andrew Loog Oldham with the Rolling Stones, or Bob Johnston’s work with Dylan. These are people who need to be talked about.

. I play a lot of Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde On Blonde. I talk a lot about [Michael] Bloomfield. Oh my God…One of the greats. The single most unsung guitar hero. Really, right there alongside the holy trinity of (Eric) Clapton, (Jeff) Beck and (Jimmy) Page. Probably next in line as far as influence and importance would be Mike Bloomfield in our early youth growing up. Extremely important.

We usually don’t play a lot of Bob’s things that classic rock stations are playing, like “Tangled Up In Blue.” I’ve programmed Rod Stewart and the Faces covering “The Wicked Messenger” from John Wesley Harding and Jimi Hendrix doing “All Along the Watchtower” from the same album.

Dylan pretty much walked away from rock ‘n’ roll for a minute, ya know, and started getting back to his roots and taking them to some other place, more the country and folk world where he came from. People didn’t know what to make of it at the time. It was a strange sort of new Bob Dylan that emerged after his July 1966 motorcycle accident.

Jimi Hendrix did more to promote John Wesley Harding than anybody. It was one of the most remarkable records ever made of course. And the fact that Jimi picked up on that from that unusual and not very popular Bob Dylan album and made everybody go back to it. And, I’m telling you Harvey, that’s how powerful that record was.

Everybody went back to John Wesley Harding after hearing Hendrix, thinking, “you know, maybe I missed something? Look what Jimi Hendrix did with it. Look what the Faces did with it.” It worked. It’s a terrific album but sort of subtle, compared to Blonde On Blonde that most people consider Bob’s peak.

Eddie Kramer: Jimi never ceased to amaze me with his choice of other peoples’ songs. And his re-interpretation of them. There’s the obvious thing like Bob Dylan. But everything he turned his hand to had this amazing other worldly kind of sound and performance to it. And re-interpreting other people’s material was one of his great assets. Witness the fact that he loved Dylan, and “All Along the Watch Tower” became his in the sense that even Dylan adopted that performance. It’s Jimi’s thing.

Janie Hendrix: Jimi really loved the lyrics of Bob Dylan. And he was one person who I met who really admired Jimi. Ten years after Jimi died my dad got a phone call. I had come home from college and he said, “You’ll never believe who called today.” “Who?” “Bob Zimmerman. Bob Dylan.”

I did the same thing. “What did he want?” “Well, he called, and said, ‘First of all, I want to give you my condolences for Jimi passing. And I know you’ll find this odd that it’s ten years later and I’m finally calling but I’ve picked up the phone so many times in the last decade and I just couldn’t bring myself to call you and talk to you. But Jimi was more than somebody that admired my music. I admired his. He was a friend. And it just hurt extremely when he died. And just wanted to pick up the phone to call you and give my condolences.’

Wow…Of course my dad was very emotional and it made him cry. “Why thank you for calling.” And Dylan said, “The next time I am in Seattle I’d like you to come to the concert.”

“So, a few years later, Bob Dylan came to town and he invited us to the show. He said, “Seattle. Home of Jimi Hendrix!” We went backstage. And, here is my dad, late ‘70s, and a little camera on his wrist and he’s got arthritis and not walking very well. But we get backstage at The Paramount in the green room. And he’s reaching for his camera, and Bob Dylan doesn’t like to take pictures, so his bodyguards almost attack my dad (laughs). “No! No!” “I’m sorry. I would like to have a picture with you.” And Bob Dylan had on his slip up hoodie and pulled the hood off and said, “It’s OK. Come on.” So, I took some pictures of them.

Curtis Hanson: I vividly remember seeing the movie Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid the first time in Westwood. I then saw it several more times. It was butchered but it was still great. And Dylan’s music was such a knockout. That score cue when Pat Garrett is walking toward that house where he will eventually shoot Billy the Kid, is just beautiful. It’s a stunning piece of music. And of course, “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door.”

It’s funny, each movie that I’ve made when I’ve gone on location, I’ve always taken that soundtrack album with me. I’ll take a dozen things I enjoy listening to but I always include that album because to play it in my car driving toward location at certain times is like tonic. “They don’t want you to be so free,” expresses the feeling that you get when you fight and lose, and yet persevere and try to win the more important battles yet to come. It brings back [director Sam] Peckinpah’s struggles. I’ve always carried that with me. It’s an important part of my musical identity.

The Wonder Boys soundtrack includes a new Dylan song, “Things Have Changed.” It started with “Not Dark Yet.” Dylan is the quintessential wonder boy. Bob Dylan, more than almost any wonder boy excels at reinventing himself decade after decade, challenging his fans and their expectations and keeping himself vital, which is what the theme of the movie is. I was in Pittsburgh scouting locations for Wonder Boys and music supervisor Carol Fenelon sent me a cassette with “Not Dark Yet” on it.

I knew the song and I knew the album, but hadn’t heard it lately. Early on, I had talked to Carol about where songs would go in the movie and we came up with a menu of scenes. One of the key musical moments was the scene where Grady and Crabtree bring James Leer back to Grady’s house. It’s a series of shots of Grady walking around in his own house and going through the journey of looking at his life. I had “Not Dark Yet” in mind before shooting that sequence and was able to plan the shots around the lyrics and music of the song. It’s all of a piece. “Shooting Star.” If you were to put Dylan aside and say, “What is the perfect visual metaphor for a wonder boy?” the answer would be a shooting star. Dylan’s great song was an obvious choice.

Unlike Grady, who was paralyzed by the success of his first novel, by the time I got some success, it liberated me. The commercial success of The Hand That Rocks the Cradle and The River Wild allowed me to make L.A. Confidential, and to make it the way I wanted to make it. And then it was the success that movie was fortunate to enjoy that gave me the leverage to do Wonder Boys the way I wanted to do it. It’s as simple as that.

Then it came together this way. Carol had lunch with Jeff Rosen, Dylan’s (music) manager in New York, and talked about the possibility of using one or two of Bob’s songs in the movie.

I learned from that meeting that Bob had been a fan of L.A. Confidential. This was very early on. I was already in Pittsburgh. Then months went by, and Carol nurtured the relationship and began discussing the possibility of a new main title song. Not long after I started editing, she arranged for Bob to come by my editing room in Santa Monica. I had never met him before. We skipped through the movie. I showed him about an hour and a half of roughcut footage and he responded immediately to the visuals of the movie, the performances, the way it felt. We talked about the themes and visual metaphors in the film. I went over bits of the plot with him so it made more sense, because there were a lot of characters to follow. He asked questions about the tempo and feel of the music I wanted.

He then went away and on tour with Paul Simon, and he called me from the road a couple of times, and we talked a little more. Then we eventually heard he was actually putting some words down on paper.

A few weeks later I get a little FedEx package with a CD inside of it. Carol came over, I knew it was coming, and we closed the door and popped it into my CD player and played this song. The themes and metaphors of the film, the nuances of the character, were all there, restated with Bob Dylan’s unique imagery and poetry. And we looked at each other and played it again and again (grins).

“Things Have Changed” is a compelling song that brilliantly captures the spirit of the movie’s central character, Grady Tripp. It’s been a long wait since Pat Garrett, but it was definitely worth it. In the video we wanted to humorously convey that “Things Have Changed,” a first-person song, is Grady’s song, and that Bob and Grady Tripp are alter-egos. The goal was to make him interact with all of the characters of the film by intercutting the new footage of Bob with footage shot for the film. We wanted him to become part of Grady’s world. The wisdom and the wit. The most gratifying aspect of the video is that it really shows the wit of Bob Dylan which is there in the lyrics anyway for those who get it. And it was fun to show his witty persona. It is so enjoyable to see people watching that video for the first time and see them laughing with Bob Dylan.

Guy Webster: What I think is happening is that the kids are relating to the intelligence behind the music of the ’60s and ’70s and they are falling in love with it. The people and their music had messages that they can relate to today. Anti-war, love, let’s all love one another, very, very Buddhist in a kind of weird way. And kids are relating to it. I know my children — without my pushing it — found Bob Dylan about fifteen years ago, and couldn’t get enough of him. That’s what started me too. I heard Bob Dylan in New York early on and I wanted to be part of that world.

In December 1965 I took photos of Bob Dylan at his Hollywood press conference, held in the Columbia Records Press Room and arranged by Billy James. You don’t work with Bob. There’s not that connection there. You just do your thing.

I wasn’t a stranger to the world of music and show business. My father, the lyricist and songwriter Paul Francis Webster, earned three Academy Awards for Best Original Song. “Secret Love,” “Love is a Many-Splendored Thing,” with Sammy Fain, and “The Shadow of Your Smile” with Johnny Mandel. His first hit lyric and music from John Jacob Loeb was in 1932 for “Masquerade,” performed by Paul Whiteman. In 1941 he collaborated with Duke Ellington.

He was very shy, like an English professor. He was brilliant and knew every word in the dictionary, all the different spellings, all the different meanings. He wasn’t threatened by rock ’n’ roll in the ’50s, because he was making big hits during the ’50s and the ’60s: “Somewhere My Love,” which combines his lyrics with the melody of “Lara’s Theme” from the film Doctor Zhivago. He was doing OK. But he didn’t like anyone except Bob Dylan. And I said, “Wait a minute, there’s a lot of guys out there!”

I told him I was going to photograph Simon & Garfunkel for an LP cover and I wanted him to meet them. I brought Simon & Garfunkel by, and my father and Paul Simon hit it off because he learned Simon was a Dickensian scholar. So was my dad. He had a Dickens collection.

Then Paul Simon said, “Hey, you want to hear our new song?” He pulled out his guitar in the living room, in Beverly Hills, and my dad was sitting there, who is not a rock and roller, and he listened to “Sounds of Silence” for the first time. “Oh my God, you guys. What a brilliant song.”

Heather Harris: You could be reading of personal discovery of the music of Bob Dylan contemporary to its creation so epiphanic to my preteen ears that I was left gasping for air like a fish out of water. Yes, he was that different from all others at the time and yes, he was that good. This was instantly perceptible even to naive prepubescent music fans like yours truly, gifted with new record albums by a caring older sibling already in college (shout out to my late brother Randall, who eventually owned and helmed a recording studio in Nashville.)

But this here article will contain far more efficient and far more lyrical treatments of the revelation that was the 1962 and beyond Bob Dylan by insightful oracles in our business that is music. My task is to remind you or even to introduce you to the rare visual talent behind him that was deemed worthy of portraying this spankin’ new icon to not only his new generation of peers, but to be sufficiently universal enough to stand the test of history right along with this music’s maker.

Fortunately, his visual legacy boasts some the last century’s best still photography artists ever to grace the medium. Dylan immediately attracted the best of the best, even beyond the promotional efforts of his hard workin’ manager Albert Grossman.

We are lucky to have the portraiture and live stage photography works of Dylan by:

(debatably the entire 20th century’s very best photographer) Richard Avedon; 1960s’ white hot chronicler, future film director Jerry Schatzberg; Jim Marshall (of way too many instantly recognizable iconic shots to list; Bob Gruen who documented Dylan from his uproarious 1965 Newport Festival electric revolution and continued to do so into our 21st Century so he is happily still here to shoot and recount the tales; Daniel Kramer (album covers of both Bringing It All Back Home and Highway 61 Revisited plus some engaging Dylan books of same); Don Hunstein (the immortal, oh so evocative The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan cover with the Village’s cutest activist couple Bob and close personal friend Suze Rotolo); and David Gahr (my only personal photography hero along with Kurt Ingham) alongside Milton Glaser (my only personal graphic art hero along with John Van Hamersveld) who designed that amazing polychrome psychedelic drawing of Dylan along the way to his I Heart NY sloganeering, in the graphics included inside the first great compilation of Dylan songs from Columbia, a poster which resided in probably three quarters of all college dormitories of the era.

Most media-savvy music enthusiasts will recognize the names in this list, with the possible exception of Rolling Stone and Creem magazine covers’ photographer (and later punk singer known as Mr. Twister who covered Highway 61 Revisited with particular elan in the gory bits) Kurt Ingham and David Gahr.

To write of the former, my late husband, might be inexcusable nepotism here so I will concern us with the often feloniously overlooked David Gahr. Peruse the book The Face of Folk Music, photographs by David Gahr, text by Robert Shelton, 1968. It contains the best/greatest/most exciting/most flattering black and white pics ever taken of each of the performers. Granted, Gahr’s own definition of “folk music” remained sufficiently elastic to have included Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention, Janis Joplin & Big Brother and the Holding Company, or any number of rockers Gahr was hired to document live, on location or in the studio.

His C.V. was whomever represented the pinnacle in modern music or soon would be. The US postage stamp featuring Miles Davis arched in an extreme but naturalistic pose wailing on horn was David Gahr’s portrait. And of course, gobs of timeless pics of a then young Bob Dylan. Because of his body of work in this very book I am a self-taught photographer. It instantaneously taught me, (not his words) the following: Flatter the subject even while extracting all the excitement possible in action gestures. Shooting natural light onstage is always superior to flash (when possible.) Make sure your timing is impeccable, no microphones covering most of the face. Document what’s there without editorializing: your own P.O.V. can be deceptively candid, as will be the subject’s. Trust your fine art background (which I had) to get unusual but perfect composition. Make sure your photos are the right value/balance/contrast to reproduce exactly as you expect. (I’ve seen Gahr’s photos in person: they look precisely as they appeared printed in books or other media.)

“If your memory serves you well…” None of us or any other recording artist or any human for that matter has ever equaled the torrential talent of Bob Dylan’s wordsmithery.

As someone who came of age in the 1960s, I was inexplicably proud when he wrote and released his Murder Most Foul in recent-ish 2020, proving to generations subsequent to his own that there still was stainless steel strength to his observations about modern history, with not a whit of loss of superconductor creativity even in an eleven- minute epic song.

Furthermore, the accomplishment of James Mangold, Jay Cocks and Timothee Chalamet in A Complete Unknown, underscores and presents context to current and future generations about why this artist was and is so revered. It’s a smart, well-cast, high caliber biofilm that not only doesn’t insult its subjects but also is worthy of them. Their memory does serve them all well.

(Harvey Kubernik is the author of 20 books, including 2009’s Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon, 2014’s Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972, 2015’s Every Body Knows: Leonard Cohen, 2016’s Heart of Gold Neil Young and 2017’s 1967: A Complete Rock Music History of the Summer of Love.

Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. In 2021 the duo wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s Docs That Rock, Music That Matters. His Screen Gems: (Pop Music Documentaries and Rock ‘n’ Roll TV Scenes) is scheduled for a 2025 publication date.