Harvey Kubernik Interviews Gene Aguilera

Q: You hail from East Los Angeles and the landmark Boyle Heights area. Tell me about the region.

A: East L.A. is a colorful barrio, proud of its cultural contributions to the world. I’m from the Boyle Heights neighborhood, almost 100%

Latino population, that has managed to stay united despite being carved up (possibly deliberately) by the arteries of an overloaded freeway system. Little as it’s known, such diverse characters as Lou Adler, Antonio Villaraigosa, Donald Sterling, Oscar Zeta Acosta, Mickey Cohen, and Anthony Quinn are from Boyle Heights.

I feel fortunate to have lived and breathed the “Golden Age of East L.A. Music” (1960s-1970s); to have witnessed the impact such Eastside groups as Thee Midniters, Cannibal & the Headhunters, the Premiers, the Blendells, and Tierra made on the Billboard Top 100 charts.

I remember crossing the bridge from East L.A. to reach the Olympic Auditorium. I grew up collecting the gorgeous floating-head boxing posters from the Olympic which was only four miles away from Boyle Heights. I used to cut out almost every Mexican American boxing story that came out in the Los Angeles Herald Examiner and the Los Angeles Times. Boxing and the East L.A. community go hand-in-hand.

Recently, I saw CNN celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain dedicate an entire episode of his show, “Parts Unknown”, to the cuisine of East Los Angeles. Watching Bourdain make it to Olvera Street to eat taquitos at Cielito Lindo (a favorite haunt of mine) made me proud to see East L.A. on the grand stage, yet sad to realize that Bourdain is now gone.

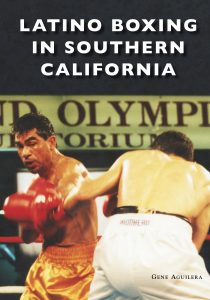

Q: You have a new book just published, a follow up to your initial volume. Tell me about the new title.

A: My first book Mexican American Boxing in Los Angeles (Arcadia Publishing, 2014) primarily centered on local Southland boxers that did battle at the venerable Olympic Auditorium; it featured prominent L.A. boxers such as Enrique Bolanos, Art Aragon, Mando Ramos, Carlos Palomino, Armando Muniz, Bobby Chacon, Danny “Little Red” Lopez, Alberto Davila, Frankie Duarte, and Oscar De La Hoya amongst others.

But during promotional book signings, people would invariably ask “Did you put the great Mexican fighters in there . . . like Julio Cesar Chavez, Ruben Olivares, Pipino Cuevas, Carlos Zarate, Salvador Sanchez, and Chiquita Gonzalez?” Many Latino boxing legends came to Southern California from Mexico, Puerto Rico, Cuba, Panama, Nicaragua, and El Salvador to showcase their fistic talents and many left with title belts wrapped around their waists.

Thus, an idea was born to honor these Latino world-class boxers with my preserved ephemera (posters, magazines, programs, photographs, and flyers) from the last 50 years. Hence the new title, Latino Boxing in Southern California (Arcadia Publishing, 2018).

Q: Explain to me some of your research methods. Long before the internet you were reading and collecting boxing magazines and reading sports writers.

A: As a young man I remember going to those old outdoor newspaper stands, especially the one on the corner of First & Soto Street in Boyle Heights. There I would buy boxing-related magazines like the sepia-colored Sports daily from Mexico called el Esto, along with The Ring, Nocaut!, Boxing Illustrated, Ring Mundial, Entre Cuerdas, and KO magazine.

My aunt Maggie Cano would bring home the Los Angeles Herald Examiner and Los Angeles Times newspapers after work everyday. A hard-working woman who supported the household, Maggie would take the RTD bus to her job as a seamstress in downtown L.A.; then bring home the dailies, which cost 10 cents each. I was fortunate to read and study the great sportswriters of the day, who were also my instructors in the sweet science, Los Angeles-style. Regaling us with their colorful and imaginative writing style were guys like John Hall, Jim Murray, Bud Furillo, Jack Disney, and Allan Malamud.

It was a natural for me to become an author because all the glorious stories stored inside of me just had to come out. I stand and applaud all the heroic Latino boxers that inspired me to write my books; I either saw them battling in the trenches at the Olympic Auditorium, training at the Main St. Gym, or read about their exploits.

Q: What did you learn from the first book that was applied to the recent one in terms of writing, captioning and assembly?

A: It took me over two years to write my first book, but it took a lifetime to collect everything on the pages. It was the first book to put together all the illustrious local Los Angeles-based Mexican American boxers in one place. Burning the midnight oil to write both books was a labor of love, never a chore. While I deliriously typed away into many deep, dark, and lonely nights; my dreams became haunted by visions of boxers featured in my books. The pressure was on to get the story right, and ladies and gentlemen, I think we did.

Writing my new book, Latino Boxing in Southern California, was a much more pleasant and easier experience than putting together my first book. In my first book, I was like a deer in headlights; it was a learning on-the-job experience. It felt like I wrote 10 books all at once. In other words, I did way too much writing and left much of it on the cutting room floor. For my second book, I knew exactly what to do. Laying it out (or the pre-planning stage) was the key and everything flowed from there. First thing I did, was to choose all the pictures that were going to be in the book, then I put them in chronological order, safely protected in plastic sheet covers in three-ring binders. Essentially I was done, that was the pre-book.

I wanted my second book to be much different than my first; which resurrected the film noir black-and- white photographs of the era. I wanted the new book to be in glorious Technicolor, with photos leaping off the pages like the bright spotlights of a movie premier. Most importantly, I wanted the book to tell the true, heartfelt stories of when boxing in this town revolved around the beloved the Olympic Auditorium and Main St. Gym while exploring the mythical devotion boxing purists and fans have for their boxers.

Q: Why did you take us deeper into this world? It’s not really a sequel but a companion.

A: I felt like there was so much more to the story. Boxing has always been my passion and there was a whole other book waiting inside of me to be written about the great Mexican ring idols who arrived from south-of-the-border to wreak havoc on the West Coast. These Latino/Mexican boxers had a major impact on boxing in Los Angeles, but did not fit into the theme of my first book. Thus my new title Latino Boxing in Southern California (Arcadia Publishing, 2018) became an essential companion, as you say.

Oscar “The Boxer” Muniz, an Olympic Auditorium favorite and former top bantamweight contender of the 70s-80s, was elated to be included in my boxing books because they ensure his legacy will never be forgotten for generations to come. Muniz recently told me, “Thanks for keeping my memory alive in your books. Now I feel secure that people will never forget what we did in the ring. I will pass these books down to my children, who will someday pass them down to their kids, all down the line.”

The Muniz story reminds me of some of my ultra rare Thee Midniters 45’s, complete with resplendent cholo writing on the label. These records do not fade away, they simply get passed down from generation-to-generation.

Q: How does your immersion in music, classic rock, pop and soul inform your writing and these books?

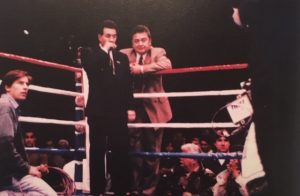

Little Willie G., lead singer of East L.A.’s Thee Midniters, stands in the ring with manager Gene Aguilera (right) as he gets ready to sing the National Anthem at The Forum before the main event in 1997. The image serves as a metaphor to a boxer getting ready for a big fight with his trusty corner man by his side.

(Photo courtesy of Gene Aguilera)

A: As a youth, I devoured the record reviews that appeared in the early volumes of Rolling Stone magazine. I became drawn to reading the review section over and over again. These writers became a huge influence in my life, and a huge influence on my writing style. From the 60s to the 70s, rock music critics like John Mendelsohn, Ed Ward, Peter Guralnick, Jon Landau, Greil Marcus, Langdon Winner, Lester Bangs, John Morthland, Joel Selvin, Gary Von Tersch, Paul Gambaccini, Lenny Kaye, J.R. Young, Robert Christgau, and Ralph J. Gleason became my mentors and imaginary best friends.

My theory is that hard work and dedication will bring out the best results to sell books (I’ve been at my bank day job for 37 years straight!). Also I was fortunate enough to manage/advise a few bands through record deals, touring, merchandise, etc. So, I put together all the knowledge that I gained in the music and real estate business and applied it to promote and sell my own books. And I did it the old-fashioned way . . . by peddling books out of the trunk of my car, making phone calls, meeting buyers at Starbucks, mail orders, book signings at local libraries/book stores, sending emails, flyers, posting in Facebook, and Instagram to let the public know that there was a boxing book out there for them to enjoy.

Q: Why did you have the impulse to bring this hidden world into the literary world. So many boxing books are about New York, or Madison Square Garden or the heavy weight division but your journey chronicled is a whole new and unique slant.

A: There have been so many great Latino boxers in history that have passed away or that are completely forgotten now. Hardy anyone writes about or mentions warriors like Salvador Sanchez, “Raton” Macias, “Pajarito” Moreno, Vicente Saldivar, Ruben Olivares, Jose Becerra, and Lauro Salas anymore. So I decided with my new book Latino Boxing in Southern California to bring them back to life here in the 21st century. I want to keep their memory alive.

Here are a few glimpses into my hidden world of Mexican ring-idols:

Salvador Sanchez: The great featherweight world champion from Mexico. I titled Chapter 5 “The Battle of the Little Giants”, after his epic 1981 victory over Wilfredo Gomez of Puerto Rico at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas. Sanchez’s short but skyrocketing career is revered in mythic proportions; defined by his victories over ring greats Danny “Little Red” Lopez (twice), Juan LaPorte, and Azumah Nelson. While in his prime, Sanchez was taken from us in a tragic automobile accident at the tender age of 23. Sanchez had 44 victories (32 by knockout) with only 1 defeat. God only knows what heights he could have reached in the boxing world had he lived a full life. And what if he ever faced Mexico’s other boxing god, Julio Cesar Chavez? It would have been a battle for the ages. His cult-like status and stellar boxing record is well-documented in my book. He left us way too soon.

Raul “Raton” Macias: Macias played himself in the lead role of a 1957 Mexican movie called “El Raton”. He graced the cover of many Mexican boxing magazines. He was on top of the world in the 1950s: a world champion, an idol in Mexico, and a movie star. You could see it in his face.

Ricardo “Pajarito” Moreno: Knockout artist “Pajarito” had a real wild side. He was the James Dean of boxing, out of control. He was so loved that his fans smashed through windows and literally hung from the rafters when they couldn’t get tickets to see his fights. “Pajarito” lived like a rock star too, driving a new Cadillac convertible through Mexico with a beautiful blond by his side.

Vicente Saldivar: Saldivar was young, confident, and ready to take over the world. He came from an era in boxing when battles were held in the bullrings of Mexico. How romantic of a notion is that? He eventually became the undisputed featherweight champion of the world. After eliminating all worthy opponents, Saldivar retired from the ring because there was no one left to seriously challenge his throne.

Ruben Olivares: I helped Ruben out towards the end of his career. In the history of boxing, he is known as one of the greatest bantamweights of all time. Ruben and I quickly became friends in 1974; a bond that’s lasted until today. We had a daily routine while training for a fight; roadwork in the morning, rest, late breakfast, then to the gym, rest, short dinner, a walk, then back to the room for the evening. He was never known to take care of himself during his fighting days and it was a struggle to keep him on the straight and narrow. If he had, he never would have lost a fight. But during his training for Chacon 3, I can honestly say he was sober as a judge. In my book, Latino Boxing in Southern California, there is a picture of Olivares and myself after a morning run at El Dorado Park in Long Beach.

Q: Can you discuss and introduce us to some of the most notable boxers who emerged from East Los Angeles.

A: Here are a few notable boxers from East L.A. proper:

Keeny Teran: A promising, baby-faced flyweight boxer from Boyle Heights. Keeny was a local teenage boxing sensation during the Pachuco era, but was later plagued by a narcotics addiction that cut his career short at age 23. Women loved and opponents feared the speedy Teran, who began boxing professionally in 1951; earning a trophy as the Olympic Auditorium’s “Fighter of Year” for starting out 12-0.

Danny Valdez: A crowd-pleasing featherweight boxer who attended Garfield High School in East L.A. From the tough Eastside neighborhood of Maravilla, Valdez won the California featherweight title in 1959.

Gil Cadilli: A flashy featherweight contender who defeated one of the all-time great boxers, Willie Pep, in a non-title bout in 1955. Cadilli was from the “Los Flats” neighborhood in Boyle Heights: attending Roosevelt High School.

Ruben Navarro: Known as “The Maravilla Kid” because he was from the tough East L.A. housing projects of the same name. A top lightweight contender who fought for the world title twice but came away empty-handed. Navarro loved the nightlife as much as boxing.

Arturo Frias: A buzz-saw style of fighter who was born and raised in the barrios of East Los Angeles. Frias attended Roosevelt High School in Boyle Heights; his story taking a dreamlike, incredible turn when he won the WBA lightweight championship in 1981 on only 11 days notice. Frias became the first boxer from East L.A. proper to win a world title in the modern era.

Joey Olivo: From the rough Ramona Gardens Housing projects in Boyle Heights, Olivo was tall (5′ 8″) for his weight class of 108 pounds. Olivo became the first ever United States-born fighter to win the world light flyweight title in 1985.

Oscar “The Boxer” Muniz: A world-class bantamweight contender who attended Salesian High School in Boyle Heights. A 10-1 underdog, Muniz delivered the first loss to WBA bantamweight champion and future hall-of-famer Jeff Chandler in 1983 in a bout televised by ABC’s Wide World of Sports.

Eddie “The Animal” Lopez: The heavily tattooed Lopez was the Eastside heavyweight champ. A tough street fighter from the Ramona Gardens Housing Projects in Boyle Heights; Lopez appeared in several prominent Hollywood boxing movies and had a controversial draw with Leon Spinks.

Paul Gonzales: The 1984 Olympic Games Gold Medalist in the light flyweight division. Attended Roosevelt High School in Boyle Heights while living in the Aliso Village Housing Projects. Trained at the Hollenbeck Youth Center by L.A. cop Al Stankie.

Adrian Arreola: Also from the gritty Aliso Village Projects and trained by Al Stankie, Arreola’s greatest triumph in the ring was a TKO victory over former WBC bantamweight champion and future hall of famer Lupe PIntor.

Oscar De La Hoya: This Garfield High School graduate is the most famous and successful Mexican American boxer from East L.A. A 10-time world champion in six different weight classes, De La Hoya also won Olympic Gold in 1992 in Barcelona, Spain. “The Golden Boy” carried the 1990s on his shoulders going undefeated until his first loss vs. Felix “Tito” Trinidad in 1999.

Q: You were just lensed for a documentary on the fabled Olympic Auditorium in downtown L.A. It was home to many

boxing matches and championships. What did the closing of the Olympic mean to you?

A: I was sad to see the Grand Dame go. Saddened forever. These days, as I drive the 10 freeway and pass by the Olympic, I always take a

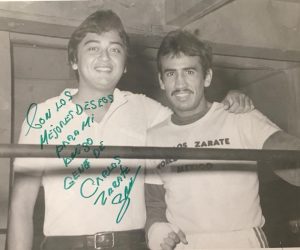

Gene Aguilera stands with WBC bantamweight champion

Carlos Zarate (right), of Mexico City, at the Main St. Gym

in downtown Los Angeles in 1977. Knockout artist and hall of famer

Zarate is recognized as one of the greatest bantamweight boxers

of all time.

(Photo courtesy of Gene Aguilera.)

quick glance to make sure she’s still standing. Yes, the shell is still there and she’s aging gracefully; but it’s a slow and painful death.

Some of the most exciting moments of my life were at the Olympic Auditorium. An unforgettable aroma of beer, hot dogs, smoke, and sweat saturated the air in anticipation of an exciting night of fisticuffs. A big part of me died, when the Olympic died.

My friend Steve DeBro is producing a documentary on the Olympic Auditorium titled 18th & Grand. He describes it as “A blood soaked tale of Los Angeles . . . set in the spectacular and seedy world of the Olympic Auditorium.” I was proud to be interviewed for it. The Olympic is a genuine, true L.A. story; ripe with historical, entertainment, and tragedy for the ages. It was a cultural phenomenon; a meeting place where all different kinds of people gathered on Thursday nights to see boxing. Can’t wait for it to come out.

The Olympic Auditorium is now a Korean Church, with the sacred Jack Dempsey murals painted over. The original marquee has been torn down. Sacrilegious. Seeing the Olympic today makes me feel like being at a wake; the body is there, but the spirit is gone.

Q: You went there. Tell me about the crowds who flocked to this legendary venue.

A: I was schooled at the Olympic Auditorium. Many people forget that Los Angeles was a fight town. Here’s hoping that my new book, Latino Boxing in Southern California, transports the reader back to a time when the axis of boxing in Los Angeles was the Olympic Auditorium and the Main St. Gym. Unfortunately, these two institutions no longer exist today.

On any given Thursday night, you would see the demure yet omnipotent promoter Aileen Eaton hold court ringside from her customary second-row seat along with trusted matchmaker Don Chargin. It was like watching L.A.’s version of boxing royalty, as Eaton barked out signals while Chargin reached for the red hotline phone under his chair to call dressing room manager Norm Lockwood to send in the next set of dueling gladiators.

The gamblers had their little section in about the third or fourth row from the ring. After a fight was over, you’d see two rows of guys stand up with money quickly exchanging hands. Chargin recalled the time when Eaton grabbed noted L.A. mobster and ex-boxer Mickey Cohen by the arm and threw him out of the Olympic for trying to take over her wrestling operations. As Don so fondly says, “Aileen was afraid of nobody.”

The stars of the day, such as Rudolph Valentino, Elvis Presley, Frank Sinatra, Connie Stevens, Richard Pryor, Mae West, Clint Eastwood, Ryan O’Neal, Burt Reynolds, Bugsy Siegel, and Charles Bukowski hugged their seats at ringside. The Olympic was really the only place where celebrities, Chicanos, gamblers, and everyone else could all mix together and enjoy their favorite sport–boxing.

There were a few times that I could not get anyone to go with me to see boxing at the Olympic Auditorium. And you know what? I went by myself.

Q: You also educate us about Aileen Eaton, who promoted the fights at The Olympic. And another promoter, George

Gene Aguilera gives his induction speech at the WBC Legends of Boxing Museum

gala at the American Sports University in San Bernardino, California on December 3, 2016. Iconic boxing writer Bert Sugar called Aguilera “an historian and trusted adviser to many Latino fighters”; in addition Aguilera’s lifelong passion to the sport and boxing books have earned him awards and inductions into several boxing hall of fame societies. (Photo by Eric Cazarez.)

Parnassus was another force bringing these fights into the arena and TV screens.

A: Aileen Eaton was the only woman in the country to promote weekly boxing shows during her tenure at the Olympic Auditorium. Called “Mrs. Boxing” by noted Los Angeles Times columnist Jim Murray, Eaton installed a star-making machinery in the development and promotion of her young fighters’ careers. She created maximum newspaper buzz around her stable of boxers. Eaton’s formula for grooming her boxers resulted in turning them into local attractions during her weekly televised boxing shows, building them up until they hit future big paydays as world champions. Beginning in 1965, Boxing From The Olympic was broadcast every Thursday night from 8:00 to 10:00pm on KTLA-TV (Channel 5), becoming the highest-rated sports television show in Southern California. The fiery redhead, Eaton, was a marketing and creative genius in charge of the longest weekly boxing club in history (1942-1980), making her the most successful female promoter in boxing history.

George Parnassus, “The Golden Greek” became matchmaker at the Olympic Auditorium in 1957 (under promoter Cal Eaton), and within a year the Olympic experienced sharp increases at its gate due to his understanding that the smaller weight classes were huge attractions to the blossoming Mexican American population. Parnassus was revered by many in the Latino community. But by 1967, Parnassus had moved down the 110 freeway to the brand-new Fabulous Forum in Inglewood to begin another successful stint as promoter, now under owner Jack Kent Cooke. Promoter Parnassus was a shrewd, silver-haired 73-year old who staged more title bouts (over 100) than any man in history, brought in the biggest gates, and was responsible for bringing big-time boxing to California. Jack Hawn of The Los Angeles Times wrote, “His favorite formula: match a Mexican fighter against anyone else. The Mexican American population in Southern California, and from south of the border, assured success.”

Prior to promoting, Parnassus was manager to three world champions–middleweight Ceferino Garcia, featherweight Juan Zurita, and bantamweight Raul “Raton” Macias; as well as legendary lightweight and fan favorite Enrique Bolanos (the top draw of Los Angeles boxing during the 1940s).

While promoter Aileen Eaton’s focus at the Olympic Auditorium was aimed primarily at the Mexican American (U.S. born Chicano) population of Los Angeles, rival promoter George Parnassus’s fight cards at the Forum attracted more the Mexican nationals. You could root for your heroes at either venue.

Q: I lived from 1963-1972 across the street from Luis Magana-Mr. Olympico, a voice of wrestling and the connection between the Olympic and the Spanish speaking world.

A: Luis Magana was the Spanish publicist for the Olympic Auditorium from the late 1930s until 1984. Magana was the liaison between the Spanish speaking boxers and the Latino press (La Opinion newspaper, KWKW radio, and Ch. 34 Univision television). Known as the “Spanish PR Man”, Magana claimed to have seen the first fight ever at the Olympic in 1925. The ever-popular Magana started his career as a fight reporter for La Opinion, and later was known to hold court nightly at La Fonda bar on Wilshire Blvd.

Q: There were other characters at the Olympic. Dr. Bernhart Schwartz, the eccentric ring doctor.

A: Dr. Bernhart Schwartz has his distinct place in Olympic Auditorium history. He was one of the Olympic’s cast of characters. Known for his white smock and frumpy appearance; a lot of people assumed he was a meat cutter at the local grocery store. I read that the doctor (early on an amateur lightweight boxer and bass viol player) had been coming to the Olympic since 1926. As the Dr. told the Los Angeles Times, “As long as there are two guys left in the world, there will be boxing.”

I once took a boxer to the doctor’s office in Watts to get his physical signed off. The lobby was packed, but we were waived in. The whole process took no more than 5 minutes and we were down the road. If you were breathing, you passed.

Q: And there was Jimmy Lennon, the ring announcer for both boxing and wrestling for 40 years.

A: Jimmy Lennon was the ring announcer for the Olympic Auditorium from 1943 to 1986. Always attired in a tuxedo and possessing a rich tenor voice, the dapper Lennon called himself, “The Irishman with a Mexican Accent.” John Hall of the Los Angeles Times wrote that Lennon’s “reputation as boxing’s most dramatic MC came mostly from his flowing Spanish introductions of Mexican fighters.” Lennon became a favorite of Mexican fight fans because of his perfect pronunciation, saying “A man is entitled to the dignity of his own name.”

Lennon had lots of scars on top of his head from all the times fans threw coins in the ring after an exciting fight. Today, his son Jimmy Jr. with nearly identical voice and looks, carries the Lennon tradition of announcing some of the biggest fights in the world.

Q: In the very early sixties, Aileen Eaton and The Olympic were involved with a young boxer named Cassius Clay.

A: Aileen Eaton can justly take credit for coming up the nickname “The Greatest” for Cassius Clay (later to be known as Muhammad Ali) and making the first pin-buttons with this moniker. Before Ali became heavyweight champion of the world, he fought three times at the Los Angeles Sports Arena under the Olympic Auditorium’s promotional banner. Ali’s fights in Los Angeles had to be held at the Sports Arena because the Olympic Auditorium (attendance 10,400) was too small. Every time Ali visited Los Angeles he always made it a point to visit his old friend, Mrs. Eaton.

Q: Yet, in your new book you came up with a description of boxing referring to it as “theatre of violent.”

A: The Olympic Auditorium has been called many things: “The Downtown Cathedral of Boxing”, “18th & Grand”, “The Cradle of Mexican Idols”, and “The Madison Square Garden of the West.” On the evening of a title fight, the Olympic carried a special magic, an electric atmosphere that permeated the entire arena. Right by the shade of the 10 freeway in downtown Los Angeles, the Olympic Auditorium hosted weekly ring-wars. I call it “A Theatre of the Violent.”

Q: Why have you been attracted to this sport?

A: I like the fact that a hungry kid from the streets could elevate himself to world champion, change the course of his family, and become the pride of his country.

Boxers would fight for their neighborhoods. There were real neighborhood rivalries that existed between barrios and you were expected to protect your own turf. Mexican American boxing fans are loyal to the end. Their love and embrace of a hometown hero never fades away. A new world champion would instinctively carry himself with a noble aura that parlayed into a celebrity status in town.

To a boxing fan, it is the greatest sport in the world. A boxer is an isolated gladiator in the ring, no teammates to help out, only your opponent stands in front of you. As promoter George Parnassus stated, “That is what it comes down to, does it not, to know which man is best.” It is sports purest form of competition.

Q: In the fifties there was the much heralded fight between Enrique Bolanos and Art Aragon. Individually and collectively they meant a lot to Los Angeles 1948-1960.

A: The 1940s were the beginning of the golden age of boxing in Los Angeles. They were the glory days of beloved lightweight contender Enrique Bolanos. It was the time of the West Coast swing era, Pachuco swagger, zoot suits, and khakis pressed tight. Bolanos, a huge Mexican American favorite here after World War II, recalled to Earl Gustkey of the Los Angeles Times, “You know, I’ll never forget arriving at the Olympic for one of my fights and seeing those long, long lines of people waiting to buy tickets to watch me fight. I remember that as well as I remember the fights, that people enjoyed watching me fight.”

If the fans cheered for Bolanos, they also booed Art Aragon (the original Golden Boy of the 1950s) just as hard. Aragon loved the role of the bad guy; he was cocky, arrogant, and a damn good boxer. He knew by thumbing his nose to the crowd, the fans would pack the Olympic Auditorium just to see him get knocked out, thus lining his pockets.

As a 22-year old rising star, Aragon met a still young 25-year-old, but fading Bolanos at the Olympic Auditorium on Valentine’s Day, 1950. In a passing of the torch, Aragon TKO’d Mexican idol Bolanos in the 12th round. This was the making of the “Golden Boy.” In their rematch a few months later, Aragon floored Bolanos again by TKO in the third round. The boos began to get even louder for The Golden Boy, with Olympic matchmaker Don Chargin recalling, “Mexican fans didn’t forgive Aragon for knocking out Bolanos.”

Q: Art Aragon was the star of Los Angeles before The L.A. Dodgers moved to town in 1958. He dated starlets, was in movies and the boxing community loved to write about his life. Describe him. He is in your books.

A: Art Aragon was the king of Los Angeles during the 1950s, becoming the city’s biggest box-office draw. Growing up in Boyle Heights, he attended Roosevelt High School before entertaining sold-out crowds at the Olympic Auditorium, Wrigley Field, and Hollywood Legion Stadium. Though supremely talented, Aragon never captured the lightweight crown, as only one world champion existed in each weight class, making a title belt difficult to obtain.

Aragon courted such Hollywood A-list starlets of the day as Marilyn Monroe, Jayne Mansfield, and Mamie Van Doren. Other than the Rams, he was the only game in town (as the Dodgers, Angels, and Lakers had not arrived yet). He was also an actor, appearing in such movies as “The Ring”, “World In My Corner”, “To Hell and Back”, and “Fat City.”

The colorful Aragon entered the ring wearing gold trunks and a gold robe; becoming known as “The Golden Boy”. Boxing magazines called him “The Bad Boy of Boxing” for his trash-talking and niteclubbing exploits. He was the California lightweight champion, a flamboyant character who counted celebrities as friends, and was married four times. Aragon’s heart will always occupy a huge section of the Olympic Auditorium; in 116 total fights he was never knocked out in the ring. Aragon was the Olympic box office champion and Los Angeles’ favorite son during the 1950s.

Q: You are friends with some of these characters who really bled within the ropes. Tell me about Carlos Palomino? He did a popular Lite Beer commercial and some acting on screen.

Gene Aguilera and singer/songwriter extraordinaire Danny O’Keefe (right),

strike a boxing pose after his show at the Coffee Gallery Backstage in

Altadena, California on October 5, 2018. Known for his 1972 hit

“Good Time Charlie’s Got the Blues”, O’Keefe was inspired by Aguilera’s

boxing books to write a new song with him called “El Corazon Mexicano.”

(Photo courtesy of Gene Aguilera)

A: Carlos Palomino was born in Mexico, arrived to the United States at a young age, and eventually fulfilled his dream to become a world champion. His first title defense against Armando “The Man” Muniz in 1977 was the first time in boxing history that two college graduates fought for the world title. In his heyday, “King” Carlos was big around here. Remember his Miller Lite beer commercial? . . . “But, don’t drink the water!” I would bump into him at niteclubs and marvel at his aura of being a world champion. Eventually Palomino retired in 1979 after a disappointing loss to Roberto Duran, but made an unsuspecting and miraculous comeback some 18 years later.

One early Saturday morning in 1997, I received a call from Carlos asking me to meet him at the Westminster Boxing Club. So I drove down there and saw Carlos in his work-out sweats and in full training mode. He asked me to help him put on the gloves, give him water, put vaseline on his face, and put in his mouthpiece. Curiosity immediately set in. Carlos was making a comeback to the ring . . . at age 47! That whole Palomino comeback story was a fulfillment (“una manda”) he made to his parents and himself. What a storyline Palomino laid out for the world to see! Yet anything is possible in boxing and I remember thinking to myself, this is why I love the sport so much.

Palomino always kept himself in great shape and he certainly proved he was up for the challenge–winning four fights in a row (all by KO) before losing to top 10 contender Wilfredo Rivera and finally retiring for good. Palomino was a colorful and popular champion–one of our best– and I will always cherish the after-fight celebrations (along with actor Edward James Olmos) at Carlos’ favorite Mexican restaurant in the Valley.

So, the Palomino action picture chosen for my book cover made perfect sense–especially with the Olympic Auditorium sign in the background. Believe me, choosing a picture for the cover of a book is a gut-wrenching experience, as there were so many other great and deserving photos.

Palomino kept himself busy as an actor when his boxing career ended, coming out in Geronimo, Taxi, Star Trek and many other movies and television shows. Here’s hoping that someday soon we get to see a movie or documentary about Palomino’s life, he has such a great story.

Q: I always liked the dude named Mando Ramos. He was the youngest man to win the lightweight title.

A: Mando Ramos was the idol of L.A. boxing during the 1960s. He lived life in the fast lane, dated Playmates, hung out with movie stars, and at age 20 became the youngest boxer in history to win the lightweight world championship by 11th-round TKO over Teo Cruz, of the Dominican Republic, at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum on February 18, 1969.

Ramos was the darling of Olympic Auditorium promoter Aileen Eaton, fighting there 27 out of his 49 total bouts. Mando, of Long Beach, California, had looks, talent, and charisma. A teenage whiz-kid who developed into a Chicano icon; Ramos was name checked in the Edward James Olmos movie, American Me. He literally grew up in front of everyone’s eyes in the Southland while fighting on many Thursday nights at the Olympic. But all this pressure led Mando to spiral into a dark world of drugs and alcohol. Mando told the Los Angeles Times, “I sold out the Olympic Auditorium in my ninth fight. Money was everywhere . . . I was 19, 20. What did I know? By 1974, I was sleeping in cars.”

Mando should be on every Boxing Hall of Fame’s list for induction; based on the mere fact that he carried the city of Los Angeles on his shoulders during the 60s. Think Broadway Joe Namath and the way he owned New York City.

Q: How do your two prime passions, music and boxing feed each other? Or does it all blend and overlap?

A: First of all, I love the whole concept of pop-culture, especially when it involves my hometown of Los Angeles. Nostalgic Angelenos still fondly recall the oft-repeated phone number of the Olympic Auditorium, Richmond 9-5171, which has been etched into pop-culture posterity.

In both my boxing books there are countless musical references; bouncing the two off each other made perfect sense to me.

Excerpts from Mexican American Boxing in Los Angeles:

A few years ago while cleaning out my garage, I found a scrapbook that my family had bought me at Disneyland back in 1961. While looking through this personal gem, I saw all the things that were important to me as a young boy. Throughout my early years, I had cut and glued pictures of my favorite British Invasion groups: the Beatles, Dave Clark Five, Searchers, and Gerry and the Pacemakers. But tucked away on one of the pages were two pictures with captions that read “Champion Cassius Clay” and “Sonny Liston.” There it was . . . I needed no more proof. In 1964 (at 10 years of age) boxing was flowing through my veins.

Top-notch guitarist Ry Cooder gets quoted from his Chavez Ravine CD, “The Olympic Auditorium, downtown, was the top-of-the-line venue for East L.A. fighters in those days. But your life can change at the end of one punch.”

Ersi Arvisu, daughter of fight manager Art Arvisu, sang with the East L.A. girl group, The Sisters, in 1964. She later sang the Eastside anthem, “Sabor A Mi” with El Chicano in 1971. The story of her short-lived boxing career is told here.

The 1980s Chapter 6 Intro page starts off with lyrics from the song “Boom Boom Mancini”, written by Warren Zevon:

“Hurry home early, hurry on home

Boom Boom Mancini is fighting Bobby Chacon”

Bantamweight contender Alberto Sandoval explains how he acquired his nickname, “Superfly” at an amateur flyweight exhbition at Chino State Prison in 1972. “It was right at the time when Superfly was out by Curtis Mayfield”, Sandoval recalled, “and in the second round, an inmate yells out, ‘Hey Superfly!’ and it stuck.”

Excerpts from Latino Boxing in Southern California:

The road to the title is not an easy one. There are struggles along the way. Singer/songwriter Danny OKeefe wrote about it in “The Prize”, a song about boxing’s up’s and downs.

“The Father of Chicano Music” Lalo Guerrero released a 45 single titled “Viva Becerra!” about the night Mexican boxing idol Jose Becerra won the bantamweight championship from Alphonse Halimi at the Los Angeles Memorial Sports Arena.

Two lp’s with legendary Mexican boxers Raul “Raton” Macias and Julio Cesar Chavez on the album covers are displayed in my book.

Four-time bantamweight champion Ruben Olivares is pictured with Mexican ranchera singer Jose Alfredo Jimenez. One of Mexico’s all-time great musical artists, Jimenez wrote a song about Olivares scintillating knockout of Efren “Alacran” Torres after an evening of drinking with the champ.

The Roberto Duran myth is immortalized in the tune “The Eyes of Roberto Duran”, sung by country/roots-music artist Chris Gaffney.

I arranged with Jim FitzGerald of Forum Boxing to have Little Willie G., the legendary lead singer of Thee Midniters (“Land of a Thousand Dances”, “Whittier Blvd.”, “Sad Girl”) sing the National Anthem before the Jorge Paez-Julian Wheeler main event title fight at the Fabulous Forum in 1997. Known as the greatest singer to come out of East L.A. , Little Willie G. is pictured standing in the ring, blowing into his pitch-pipe, getting in-key to sing the Anthem. It was a surreal experience to be standing there next to him, so close to the action, in front of a large audience, and on live TV. I love this picture because to me it serves as a metaphor for a boxer getting ready for a fight with his trusty corner man by his side.

Q: I guess the current mixture has to be a song you’ve just written with Danny O’Keefe.

A: I’ve always been a fan of Danny O’Keefe since his big hit “Good Time Charlie’s Got The Blues” in 1972. I have all of his vinyl lp’s. Once I discovered Danny was a boxing fan, I sent him my two boxing books. He really enjoyed them and was inspired to write a song about boxing–Mexican Style. Last year Danny was on tour in Southern California and we made plans to get together at my home to kick around some lyrics.

Danny had the master blueprint of a song in his head, and out of this came “El Corazon Mexicano” (“The Mexican Heart”). Gracias Danny for your friendship and generosity and I can’t wait for the song to come out.

Q: We have discussed the heritage and legacy of East L.A. music. As you know, I’ve been a lifelong advocate and supporter of the community and the sounds of this world. Why is it still overlooked and rarely documented? No Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductees, yet a slew of recordings were big hit records. And a lot of these groups from the sixties and seventies still work and tour.

A: If record executives back in the day would have dared venture out of their leather seats and gone out to East L.A., they would have found and awoken a sleeping giant. They would have unearthed a buried treasure of music that was as different and creative as any music of the day coming out. “The Golden Age of East L.A. Music” was the 60s, and yes, they tossed a bone or two out to us (meaning the major labels released a one-time 45 single to a Chicano act; such as Warner Bros. distributing “Farmer John” by the Premiers, Reprise Records issuing “La, La, La, La, La” by the Blendells, or Atco Records putting out “I Who Have Nothing” by Little Ray). But as far as building a career or releasing an extensive backlog of music (i.e., a catalog of lp’s), it just didn’t happen for East L.A. artists. We had a unique style of music; which was a blend of R & B with the British Invasion sound. We had rock ‘n’ roll, garage, psychedelic, and soul; all blended into one pot . . . and it was delicious.

Today, you still can see Thee Midniters (with original lead singer Little Willie G.) and Tierra in large venues, such as the Honda Center in Anaheim or Primm Valley Casino in Nevada. So don’t put us in a drawer yet, we’re not ready for the mothballs. There’s still lots of time to do some damage.

There’s an East L.A. underground, indie duo going on right now called Thee Lakesiders. They sing cool, look cool, and dress cool. They are influenced by people like Ritchie Valens and Rosie & The Originals (“Angel Baby”). I was once doing a boxing book signing at a library in the South Bay area and as I looked out into the audience, I saw this couple who looked familiar. Right away I recognized them as Thee Lakesiders. I proceeded to introduce them and you should have seen the look on their faces. Never did they think that anyone would know who they were in that setting.

Anyway, if you get a chance, check them out.

Q: Rock and roll music documentaries almost always leave out East L.A. Ritchie Valens is cited but he’s from Pacoima in The San Fernando Valley.

A: The East L.A. music scene is like a forgotten stepchild. We are around, but somehow left behind when the goodies are passed around. We seldom get mentioned in rock ‘n’ roll music docs or music history books, even though we had plenty of Billboard Top 100 charting hits.

Technically Ritchie Valens was from the Valley, but to East L.A, he was one of our own. A darn shame that we had to lose him at the ripe young age of 17 (even at that point, Valens already had three big hits to his credit: “La Bamba”, “Donna”, and “Come On Let’s Go”).

Q: I am not drawing any comparisons or accusing anybody of sonic theft, but bands who have had some horns or brass in the action were prominent in many East L.A. bands, long before Chicago and Blood, Sweat & Tears. Although Al Kooper’s BS&T was heavily influenced by Maynard Ferguson, and Chicago were an extension from The Buckinghams.

A: East L.A.’s Thee Midniters, who released their first record in 1965, were possibly the first rock ‘n’ roll band with a full-time, working, and recording brass section. They were the forerunners to all the groups you mention above. It is a seldom mentioned fact in today’s rock literary world that Thee Midniters were probably the first rock ‘n’ roll band to incorporate horns into their live performances and recorded music canon. This must be corrected.

Case in point for rock’s first horn band: The Buckinghams came out in 1967. Blood, Sweat & Tears and The Electric Flag released their first records in 1968. Chicago Transit Authority (later Chicago) put out their first lp in 1969. Thee Midniters charted in 1965.

Q: What is the future of boxing and the world from the fifties-seventies that you are pre-occupied with?

A: I appreciate the fact that boxing is a real art and science, but unfortunately these days it is becoming less of that and becoming more of a business. Many bouts these days look like sparring matches. It seems the boxers want to make to another day without taking risks. The boxers of today fight like they are in survival mode. You don’t see the knock-down, drag-out fights that you used to see in the old days. Big money paydays has ruined boxing; it takes the hunger away.

But for boxing to make through the future, promoters need to scour the streets and look for the next Oscar De La Hoya, et al. We need personality and talent to save the day. Aileen Eaton of the Olympic Auditorium knew how to develop a boxer into a star. Nobody seems to know how to do that these days.

Q: I know you still go to fights and see a lot of pay-per-view exhibitions and championship matches, but it all seems so corporate and lacks the smell of the street.

A: The whole landscape of watching boxing on TV is changing, due to the power of the internet. For the past many years, Saturday night boxing (whether on HBO or Showtime) was a must-see at the Aguilera household. Now it’s all rapidly changing right before our very own eyes. HBO just pulled the plug on televising boxing after 45-years. It seems the suits back east saw something that we didn’t see right away. The big names of recent boxing (Mayweather, Pacquiao, the Klitschko’s, Marquez, Hopkins, Cotto, etc.) have either faded away or retired, and the up-and-comers don’t seem to have the gravitas or charisma to replace them. Now it’s either DAZN (a paid subscription video streaming service which is like the Netflix of sports) or ESPN+ (which is another subscription service through their app.) I personally don’t like any of this, as many of the bouts are not worthy of these extra charges. It’s like they’re sneaking up full-time PPV programming on us with only mediocre bouts to show for.

Q: You still collect records and catch heritage acts when they headline L.A. And, over the last 20 years downtown L.A. has become again the center of live music entertainment.

A: Last July 24, 2018, I caught The Byrds live in concert at the Ace Hotel in downtown Los Angeles reprising the 50th anniversary of their seminal country-rock album, “Sweetheart of the Rodeo.” It was original co-founding members Roger McGuinn and Chris Hillman backed by country singer Marty Stuart and his Fabulous Superlatives. It was a can’t-miss show for me, as many critics say this lp started the country-rock movement.

A few months later on November 16, 2018 in West L.A., I saw Richie Furay at the world-famous Troubadour club. Furay (who was in Buffalo Springfield, Poco, and the Souther-Hillman- Furay Band) is one of country-rock’s pioneers and hasn’t lost a step. He still sounds great.

Q: In the last couple of years since I’ve interviewed you, what have been some of the rare records, albums, and vinyl you have picked up or purchased?

A: I was recommended by dj friend Humberto Terrones about this hip, new record store in Boyle Heights called “Sonido Del Valle”. It’s a cool hang because apart from having live in-store performances there, the front part is a separate used book store. On the day I wandered in, I saw this cult album collectible, “Songs of Protest and Anti-Protest” hanging on the wall. This rare piece of vinyl was released way back in 1965 under the name of Chris Ducey on Surrey Records, but later changed to Chris Lucey (due to a contractual snafu) but whose real name was folk-singer Bobby Jameson. If this is not confusing enough, the album front cover has a photo of Rolling Stones guitarist Brian Jones flipping you off (making it suitable for the title of this LP) while he’s blowing on harmonica.

In his book Double Vision, photographer George Rodriguez said, “This was taken at a Sunday afternoon jam session at The Action on Santa Monica Boulevard {near Barney’s Beanery}. You never knew who you would see. Brian Jones did these harmonica solos that would last for about half an hour. My shot of him ended up on the cover . . . The Action would put my photos on their walls so I assumed that’s how they got it. Someone told me they saw my photo on an album cover at Wallichs Music City and I was pretty surprised.” Rodriguez later told me, “I immediately went to Surrey Records, which was this low-budget label, and told them they owe me for using my photo on their album cover. They wouldn’t pay me. I figured someone at the club must have took the photo down and sold it to the record company. Later I heard the Stones sued the record company but I don’t know what happened.”

Needless to say, I bought the album and took it home.

I also want to give special mention to an album I worked on as “Creative Consultant”, called “Music Is The Answer” by God’s Children (Minky Records, 2017). These long-lost 1971 sessions from East L.A. supergroup God’s Children featured lead vocals by Thee Midniters’ Little Willie G., soul belter Lil’ Ray (“Shake! Shout! & Soul!”) and local female stylist Lydia Amescua. Originally, God’s Children released two 45-singles on the Uni label; but to me, they were the Chicano answer to The 5th Dimension. Thank you to Rampart Records for rescuing these long-forgotten tapes from their vaults.

Q: And, can you give us a tip on record collecting or the how you navigate this audio arena?

A: Pick up a copy of Record Collector Magazine, inside their pages you will find all the new and old hip record stores in the great state of California that are happening today. There’s nothing like going to a record store and finding a record that’s on your want-list. Support your local record stores and buy vinyl.

(Harvey Kubernik is an author of 15 books. His literary and music anthology Inside Cave Hollywood: The Harvey Kubernik Music InnerViews and InterViews Collection Vol. 1, was published in December 2017, by Cave Hollywood. Kubernik’s The Doors Summer’s Gone was published by Other World Cottage Industries in February 2018.

During December 2018, Sterling/Barnes and Noble published Kubernik’s The Story of The Band From Big Pink to the Last Waltz. This century Harvey penned the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special, The Ramones’ End of the Century and Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish.

Kubernik’s writings have been printed in several book anthologies, including The Rolling Stone Book of the Beats and Drinking with Bukowski. He is the project coordinator of the recording set The Jack Kerouac Collection.

In November 2006, Harvey Kubernik was a featured speaker discussing audiotape preservation and archiving at special hearings called by The Library of Congress and held in Hollywood, California. Harvey literary and musical expeditions are displayed on Kubernik’s Korner at www.otherworldcottageindustries.com.