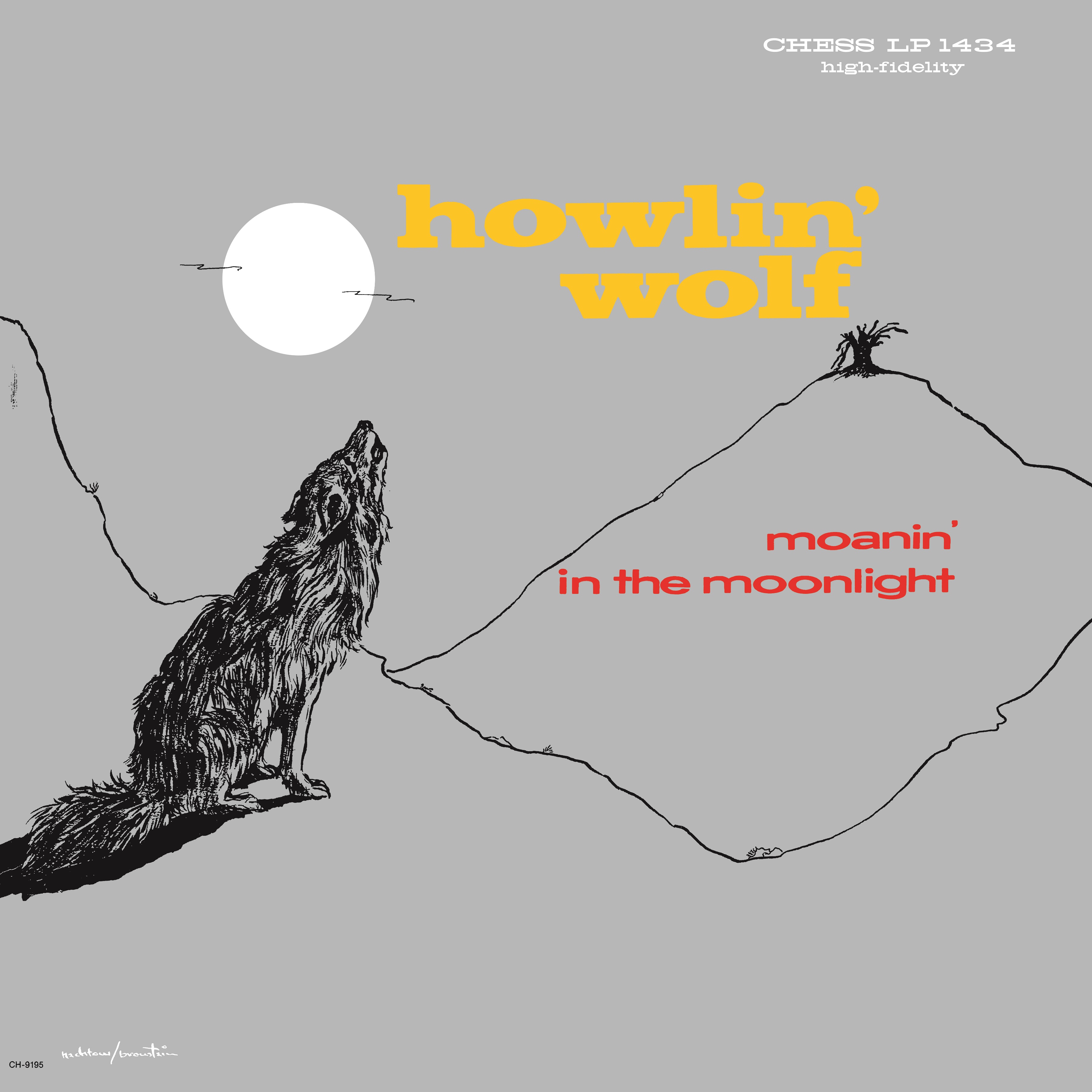

REISSUED ON VINYL AHEAD OF 60TH ANNIVERSARY

By Harvey Kubernik © 2018

Chester Arthur Burnett, (June 10, 1910-January 10, 1976) better known to blues fans as Howlin’ Wolf, remains one of the essential

exponents of the electric blues. With a raw, booming voice and explosive guitar and harmonica styles to match, the Mississippi-bred Wolf made music that was unmatched in its primal ferocity.

In the process, he, Muddy Waters, Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry, Buddy Guy, Fontella Bass, Billy Stewart, Etta James and others helped to put the Leonard and Phil Chess owned Chess Records on the map as America’s preeminent blues label.

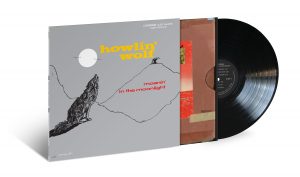

Now, just in time for the 60th anniversary of Moanin’ In The Moonlight’s original high-fidelity release, Geffen/UMe has made available a special vinyl edition of the mono album.

Remastered from the original flat master tape, this new edition features a high quality 150-gram black vinyl pressing housed in a printed sleeve with scans of the analog tape box and comes in a distinctive tip-on jacket reproducing the album’s distinctive original cover artwork by

Don S. Bronstein. The LP displays the 1959 liner notes from Billboard editor Paul Ackerman.

Howlin’ Wolf performed throughout the South in the 1930s and 1940s, having reportedly learned to play guitar and harmonica from legendary bluesman Charlie Patton and Sonny Boy Williamson, respectively.

He was discovered in 1951 by deejay/musician and talent scout Ike Turner, who steered him to future Sun Records founder Sam Phillips, who recorded Wolf’s early sides, some of which he licensed to Chess. Howlin’ Wolf eventually relocated to Chicago Illinois and began recording for Chess directly.

Like many LPs of the period, Moanin’ In The Moonlight includes tracks stretching back several years, including a trio of numbers—”Moanin’ at Midnight,” “How Many More Years” and “All Night Boogie”—recorded in Memphis in the early ’50s with Sam Phillips.

The album’s nine remaining songs were recorded after Wolf’s move to Chicago and produced either by label owners Leonard and Phil Chess, or by staff musician/songwriter Willie Dixon.

Moanin’ In The Moonlight features four songs that had been hits on Billboard’s national R&B charts: “Moanin’ at Midnight”, “How Many More Years,” “Smokestack Lightning” and “I Asked for Water (She Gave Me Gasoline).”

In the years since his passing in 1976, Howlin’ Wolf has been widely recognized for his musical achievements. He is a member of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, the Blues Hall of Fame, the Memphis Music Hall of Fame and the Mississippi Musicians Hall of Fame. Meanwhile, the Howlin’ Wolf Foundation continues to preserve and extend the artist’s legacy.

Moanin’ In The Moonlight continues to be singled out for individual praise. In 1987, the album received a prestigious W.C. Handy Award under the category of “Vintage/Reissue Album (US).”

Although Howlin’ Wolf would release new albums for the next decade and a half, it’s widely agreed that Moanin’ In The Moonlight is the definitive document of his remarkable talent.

And now it can be heard once again, in all of its original vinyl glory.

MOANIN’ IN THE MOONLIGHT TRACK LISTING

SIDE A

- Moanin’ At Midnight

- How Many More Years

- Smokestack Lightnin’

- Baby, How Long

- No Place To Go

- All Night Boogie

SIDE B

- Evil

- I’m Leavin’ You

- Moanin’ For My Baby

- I Asked For Water (She Gave Me Gasoline)

- Forty-Four

- Somebody In My Home

I was startled by my first glimpse of Howlin’ Wolf in 1965 on the Jack Good-produced and Los Angeles-based Shindig! television series when he was a guest with The Rolling Stones where I attended a slew of ’65 tapings at the ABC-TV studios on Prospect Ave. He looked like a massive linebacker on The Los Angeles Rams football team!

I remember hearing about Howlin’ Wolf coming to L.A. in 1968 when he was booked for a concert in the Girls Gymnasium at Valley Junior College.

Around the same time in June ’68, Wolf performed at the Ash Grove (1958-1973) an all ages-blues and folk club on Melrose Ave. just 400 yards from my Fairfax High School. In February 1972 Wolf was on a show at the legendary Hollywood Palladium with Commander Cody and his Lost Planet Airmen headlined by Alice Cooper.

Wolf’s primitive and seductive recordings received very little airplay in the Southern California radio market but I knew about him. Keith Richards and Brian Jones of the Stones had earlier mentioned Howlin’ Wolf along with Muddy Waters and Chuck Berry in numerous music magazines I devoured.

Deejay Wolfman Jack on his south of the border Mexico radio station broadcast shifts on XERF-AM in 1964 and XERB-AM in 1965, both reached Southern California, spun Wolf late at night, while KRLA and KFWB, AM radio outlets in Pasadena and Hollywood, devoted 1965-1968 airplay to cover versions of Howlin’ Wolf’s songbook from The Rolling Stones, Yardbirds, Animals, Fleetwood Mac and The Jeff Beck Group. Cream’s ’68 cover of his “Sittin’ on Top of the World” was in KMET-FM’s rotation.

There was a local band at the time, Smokestack Lightnin’ who played the Whisky a Go Go in Hollywood and had an album out, Off The Wall. There was even a note on a bulletin board one afternoon in a hallway at my Fairfax High School from a candy striper alerting students about Howlin’ Wolf receiving dialysis treatment at the Veterans Administration building. Wolf spent two-and-a-half years in the US Army and at the time was suffering from kidney disease.

On occasion over the last 50 years I asked several friends and music business veterans about Howlin’ Wolf.

Earlier this century I interviewed Marshall Chess, former president of Rolling Stones Records, whose father Leonard, and his uncle Phil Chess initially product -shipped Moanin’ In The Moonlight via the Chess Producing Corp.

Marshall and I talked about Howlin’ Wolf and Chess Records.

“Bill Graham at the Fillmore venue in San Francisco was the greatest for the blues artists of that era. B.B. King on the bills. FM radio was a Godsend for the blues. The big commercial AM stations would not play the records at all except some black stations. And I decided to repackage Chess to that market that was getting stoned and going deep. It was a big boost when the English groups covered the music earlier. On records and at their shows.

“We loved it and something we thought could never happen. Muddy Waters and B.B. King really dug white people doin’ their stuff. Sonny Boy was very much into white people doin’ his stuff. So was Howlin’ Wolf,” enthused Marshall.

“I remember (Eric) Clapton gave him a fishing rod. Wolf was a real sportsman. He had fuckin’ huntin’ dogs that were a thousand dollars each. It blew our mind.

“Howlin’ Wolf on stage very commanding, but off stage a very gentle, soft man. I remember him telling me he was learning how to read music. Did you know that? He went to school to learn how to read music so he could learn how to play the guitar. He wanted to learn notes.

“One time my dad had me bring him a thousand dollars to his house, and he opened up those tool boxes that you lift off the tray at the top. And it’s stacked full of money. ‘What do you need this money for?’ ‘I gotta go buy some special dogs to go huntin’ on my farm.’ (laughs). He was a gentle man but ferocious. Big. He used to drink a lot. He was pretty much high a lot when he performed.

“I think Willie Dixon was a great songwriter, a great promoter, a real hustler and he was a great guy. He was very important to the success of Chess and I will not take that away from him. He’d get the bands together. He wasn’t Chess at all. But he was an important part of Chess Records. Very important part of that blues era.

“The Chess recording artists were always writing about women problems and sex. That’s all I ever heard from them when I was a kid. I always say this and people laugh. That was the main thing on their mind. Look at their lyrics. I saw some of these records being recorded. I sold them originally.”

Howlin’ Wolf made an impact on Bob Dylan, who called him “the greatest live act.” Dylan sang “Smokestack Lightnin’ in March 11, 1962 on Cynthia Gooding’s radio program.

In December 2016 I interviewed Robbie Robertson of The Band. He marveled at the mention of Chess inside his office at Village Recorders

“When I heard these early Sun and Chess records I thought, ‘what is going on here? The sound coming out of Chess Records in Chicago… What kind of a room is that? What is this magic?’”

Marshall explained the sonic history of the Chess studio.

“In the early days Chess utilized the Universal studio. The Weiner brothers designed the Chess studio. Chess employed great sound engineers like Malcolm Chisholm and Ron Malo. Weiner and Chisholm came from Universal.

“Then we built 2120 S. Michigan Ave. Jack Weiner was our original engineer. He built the console. Two Ampex 350 tape machines and Electro-Voice speakers on the wall. We then started experimenting with all kinds of echo.

“The Chess studio had the echo chamber in the basement, very small control room. One of the secrets of the Chess studio was not the studio but our mastering. We had a little mastering room with a lathe. Eventually we had a Neumann lathe. The first one was an American one. We did our own mastering. The great part about that room that when it sounded right in that mastering room it would pop off the radio. That’s what it was all about.

“These artists were great and would have been great in any studio. It was the artistry, the playing. The studio was great and we captured a sound, and it had a sound, but it was our artists that made that sound,” reinforced Marshall in our two-hour chat.

“All these magicians came to Chess. It’s something that can be experienced through audio. The music has stood up without a cinematic aspect like video and the method of recording. As I grew older, and was a person of the hippie generation and I discovered things like meditation, psychedelic drugs, and Buddhism. I realized what was happening in the early Chess studio was like a high Buddhist monk meditation manager. Because when you recorded in mono and two-track with 5 or 6 players and a singer there wasn’t any correction possible.

“One of the main jobs as a producer was like a meditation manager master. He had to get the band locked together to go down. The thing that this early music has is that it just has some fuckin’ kind of magic in it. I think maybe it’s the direct to two-rack recording of the period. I don’t know what it is. Some kind of alchemy. A real esoteric alchemy. That’s what drew the first telephone call from Andrew Loog Oldham with the Rolling Stones to record in our studio.

“They did a song about our address at Chess ‘2120 South Michigan Ave.’ I was there during those sessions. I used to fill out orders from England before I ever knew, or realized some came from Mick Jagger. Brian Jones loved the blues and was in awe of Chess. I remember packing up some Chess LPs for the Stones as a gift and taking them on a tour of the offices and introducing them to Phil and my father Leonard in the back office that they shared.”

During 1964 and ’65, The Rolling Stones’ manager, publicist and record producer, Andrew Loog Oldham had arranged for the band to come to the famed Chess Records studio in Chicago.

In a 2006 email interview to me Andrew detailed their visit.

“It was Chess records, the vinyl actuals that re-united Mick Jagger and Keith Richards on Dartford Station in 1962. It was Chess Records, the company, the work that drove Brian Jones to form the Rollin’ Stones.

“It was Chess Records – the wave, that came over me in the Station Hotel in Richmond in April ‘ 63 when I first saw the Stones and we began our way of life together. Chess was always the underbelly of the Stones beast; the fuel that charged the engine, even after they became their own brand.

“The first US tour by the Stones was not the Beatles tour. We had a cult following in the cities and were abandoned in the sticks. The boys needed cheering up. I could not have them de-planning in London looking like the brothers glum.

“I called Phil Spector from Texas where the Stones had just supported a band of performing seals and asked him to get us booked just as soon as possible into Chess studios. Phil or Marshall Chess called back and said he’d set up two days of recording time, two days hence.

“Chicago was a piece of heaven on earth for the Stones. The earth had been scorched on most of our mid-American concert stopovers. We hadn’t set any records; we didn’t yet have the goods, apart from a trio of wonderful one-offs, ‘I Wanna Be Your Man,’ ‘You Better Move On’ and ‘Not Fade Away’ we had yet to find our vinyl legs.

“2120 South Michigan Avenue housed Chess Records and studios and in two days the group put down some thirteen tracks-their most relaxed and inspired session to date-moved, no doubt, by our newfound ability to sell coals to Newcastle. Who would have thought a bunch of English kids could produce black R ‘n’ B in the States? And here they were in the sanctum sanctorum of Chicago blues, playing in the lap of their gods. The ground floor was a gem, as was Chess engineer Ron Malo. He treated them just like…musicians.

“Nothing sensational happened at Chess except the music. I was producing the sessions in the greatest sense of the word: I had provided the environment in which the work could get done. The Stones’ job was to fill up the available space correctly and this they did. This was not the session for pop suggestions; this was the place to let them be. Oh, I may have insisted on a sordid amount of echo on the under-belly figure on ‘It’s all Over Now,’ but that was only ear candy to a part that was already there.

“I can remember being impressed with the order of things and how quietness and calm got things done. I remember meeting Leonard and/or perhaps Phil Chess, and being cognizant of the fact that there was no suppressive limey stymieing from the head office to the factory floor. There was just a factory floor and a very relaxed combo of artists, musicians, engineers, and salesmen all at one with each other and getting their jobs done and royalty Cadillacs royally driven.”

It was Andrew Loog Oldham who encouraged the group to record “Little Red Rooster,” written by Willie Dixon and cut by Howlin’ Wolf, and then brought it to the Decca Records label to press as a single. It subsequently topped the charts in the UK. Andrew insisted his lads perform “Little Red Rooster” on television in 1964 on Ready, Steady, Go! in England, and during 1965 on Shivaree! and Shindig! in the US.

“Willie Dixon thought we were naïve white kids who didn’t know these songs. He tried to pawn a song on us,” bassist Bill Wyman, Rolling Stones’ co-founder told me in a 2002 interview.

“Keith talks about how he saw Muddy painting the walls at Chess. It’s funny. It gets headlines and it gets a laugh. Muddy did help us in with the gear. It’s in my diary that day. The greatest thing about Chess Records wasn’t the recording, or having Buddy Guy walk in, Muddy, and Chuck Berry coming and saying ‘Swing on, gentlemen, you are sounding most well, if I may say so,’ and he knew he was going to make some money. But it was being told we could go down in the cellar and pick some albums if we wanted. Racks of Little Walter albums we had never seen. That was the magic of Chess for us. And me plugging into a plug direct for the bass. Direct!”

In our 2002 conversation, Wyman and I ruminated about his blues heroes. The Rolling Stones’ live repertoire over the decades had included Howlin’ Wolf’s “Down in the Bottom.” Wyman in his Stone Alone book also discussed their band’s rendition of the Smokey Robinson-penned “My Girl,” a hit for The Temptations, heard on the Rolling Stones’ Flowers. Wyman admitted he had a very tough time getting the bass part down.

“It was just the wrong way around for me,” stressed Bill. “And if I listen now to ‘Smokestack Lightnin’’ by Howlin’ Wolf, Willie Dixon plays the bass backwards on that. And I’ve only noticed that in the last ten years,” he marveled.

Record producer, manager and blues advocate Denny Bruce, who played drums with Frank Zappa in 1965, came to Los Angeles in 1963, and attended Valley Junior College when he was first exposed to Howlin’ Wolf.

“I had just moved from Philadelphia. One day I hear somebody playing a flute, near the Quad, and get closer to check it out. A cat with a goatee, wearing a sweat shirt with the sleeves cut above the elbow, is playing meditative stuff that seems to have him chilled out,” Denny recalled.

“We meet. His name is Lowell George. We talk about music, and he said he would drive me to Hollywood some night, and turn me on a few places. The first stop was a small coffee shop, a real hangout spot, called Fred C. Dobbs. He goes straight to the juke box, puts in some change and ‘Little Red Rooster’ by Howlin’ Wolf plays.

“I saw The Rolling Stones do it on The Ed Sullivan Show, but the power of hearing this, and how great the slide guitar work was done, blew me away! [George and his Little Feat band covered ‘How Many More Years’ and ‘Forty-Four Blues’ on their debut LP]. This was years before the sound of a slide guitar became a commercial gimmick that you still hear in TV commercials.”

In 1968 I bought my copy of Moanin’ In The Moonlight from Chris Peake one afternoon who managed the Ash Grove record section. Denny Bruce brought Keith Richards into the room and collector Keith immediately laid out $75.00 for the 1965 TCH Hall Records LP The Cool Sounds Of Albert Collins, which Denny leased and re-released in 1969 on the Blue Thumb Records label as Truckin’ with Albert Collins.

During a 2000 interview with arranger/producer and songwriter, Jack Nitzsche, we discussed Howlin’ Wolf’s memorable televised Shindig! appearance.

“I spent a day with him on the set of Shindig! I went down there with the Stones, and Sonny & Cher were there, too. Sonny introduced me to Howlin’ Wolf and I was speechless. He was imposing. There was a sweetness in there you could see. And anyway, we were sitting there for a long time and he was sitting next to me and he had a friend with him who was a little older, and strange. He wore a cowboy hat, boots and a bolo tie. Western attire. We sat together and I was content just to sit and not even speak. Just to be in the man’s presence, ya know. So, after a while, we got to talking and he became more comfortable. So did I. He said, ‘I didn’t introduce you to my friend. Jack, this is Son House. . .’ I’m sitting with Howlin’ Wolf and Son House. I saw the Stones sitting around Howlin’ Wolf when he performed.

“You should have seen the take they stopped…They made him stop in the midst of a take. ‘Cause he was like 300 pounds. Huge and he had a toy harmonica, a tiny harmonica that he would put in his mouth. He could hold it between his lips. Oh man…So, he got up there on stage to do his set and he put that little harmonica in his mouth. That was the surprise. The band was playing, and it came time for the instrumental and he was kinda dancin’ around when he came up again for air, he was playing harmonica and holding the microphone. It was theatrical and funny stuff for the fish fry. I had to use a Wolf track on Blue Collar.” [“Wing Dang Doodle”].

The influence of Howlin’ Wolf was very apparent on The Doors. Chicago-born keyboardist Ray Manzarek touted Howlin’ Wolf’s catalogue to me.

Ray had first heard his records on deejay Al Benson’s influential Chicago radio program. The Doors’ debut album subsequently waxed Wolf’s “Back Door Man,” that was immediately introduced to the pivotal Los Angeles market by deejay Dave Diamond on his 1966-1967 KBLA-AM Sunday night program.

In a 2006 interview with me, Manzarek acknowledged Wolf’s impact on “Light My Fire.”

“First of all, the left hand created that hypnotic Doors’ sound. For instance, during the ‘Light My Fire’ solo section, it’s an A-minor triad to a b-minor triad that just repeats like (John) Coltrane’s ‘My Favorite Things.’ The same sort of modal chord structure that Coltrane used in ‘My Favorite Things.’ Left-handed I’m playing the same thing over and over.

“The right hand is just playing filigrees, comping behind Robby Krieger, punctuating with chords, punctuating with single notes playing with Robby Krieger. When I’m soloing I’m playing anything I want to play. And that bass line just keeps on going. It never varies and it never stops. Over and over like tribal drumming or Howlin’ Wolf playing one of his songs without any chord changes. On and on and on. The same pattern.”

Singer/songwriter Danny Gravas knew and worked with Howlin’ Wolf at clubs and ran a ‘60s workshop with him at The Newport Folk Festival. Danny started his music career in the East Village in New York, and then the coffee houses of Boston, sharing dates with the likes of Tom Rush. Gravas was the first President of the Boston Folk Guild.

Travis Pike, a singer/songwriter met Danny in 1966, when he walked into King Arthur’s, the coffeehouse with a liquor license in Boston’s “Combat Zone,” so designated by the natives because it was Boston’s entertainment district, explored on weekend liberty by the many G.I.s stationed locally or on Naval vessels in port.

In 2018 Pike connected me with Danny Gravas who emailed me about Howlin’ Wolf.

“My take on ‘The Wolf’ was probably different than most. At the time, I was playing a lot of Delta blues. As you know most people thought I was, at the very least, a mix of black and white, so I had a special in with so many black performers. ‘The Wolf’ treated me like one of his family and let me play when he did even though I was not booked there. To me, he was a big cuddly bear, a kind and willing mentor.

“I was appalled by his portrayal in the movie Cadillac Records.

“He was never overtly aggressive, nor did he carry himself in that manner. If Wolf felt people were prying, he would either be quiet or join the other black players. They had a special way of talking, consisting of looks, grunts and a black lingo. I was one of the few white performers to ever play in his club in Chicago called The Gilded Cage. If I had to guess who else played there it would be John Hammond, Jr. John was very well-respected among the black performers.

“Remember ‘The Wolf’ was at least 6 foot three and at least 340 pounds. He was huge. I was amazed at how he played a guitar with such huge fingers, or a harp that when he held it couldn’t be seen in his hand.”

In 1969 multi-instrumentalist Chris Darrow caught the Howlin’ Wolf experience in Chicago.

“I remember the first time I heard Howlin’ Wolf; I couldn’t believe it, I was mesmerized. The sound, the tone, the dark strength got to me as a 17-year-old boy in 1962. Moanin’ in the Moonlight was the album that had so many classics on it, but ‘Smokestack Lightnin’’ was it for me.

“So years later, while gigging with Linda Ronstadt in Chicago, on a bill with Tim Buckley and Aliotta Haynes, at the Chicago Ampitheatre Auditorium, I was fortunate enough to see Wolf perform in a Southside club. It was late in his life but he was all there. He was backed by his famous, long time guitarist, Hubert Sumlin, whose tie, suit and shoes matched in color, a kind of golden, mocha hue. Elegant man. Elegant player. The music was fabulous and the experience was right.

“Wolf was not the scary guy of his younger days, but he still had it. He was about sixty and didn’t stand up all the time while he was singing. However, he could still sing and it was a thrill to actually be in the same room with him, having a cocktail and groovin’. I always feel that it’s important to acknowledge an artist when you can, so we paid our respects to him and his band. The dignity of this legendary great was totally apparent. He thanked us graciously and we walked out into the night a lot better off for what we had just done.”

Director Don McGlynn’s documentary The Howlin’ Wolf Story-The Secret History of Rock is available at https://www.amazon.com/Howlin-Wolf-Story-Secret-History/dp/B0000DJZ81.

(Harvey Kubernik is the author of 15 books, including heralded titles on Leonard Cohen and Neil Young. His 2017 volume, the acclaimed 1967 A Complete Rock History of the Summer of Love was published by Sterling/Barnes and Noble. Inside Cave Hollywood: The Harvey Kubernik Music InnerViews and InterViews Collection, Vol. 1 was published in December 2017, by Cave Hollywood. Kubernik’s The Doors Summer’s Gone was published by Other Cottage Industries in March 2018.

In November 2018, Sterling/Barnes and Noble published Harvey’s book, The Story of The Band From Pig Pink to The Last Waltz, written with brother Kenneth Kubernik.

During November 2006, Harvey Kubernik was a featured speaker discussing audiotape preservation and archiving at special hearings called by The Library of Congress and held in Hollywood, California).