By Harvey Kubernik c 2018

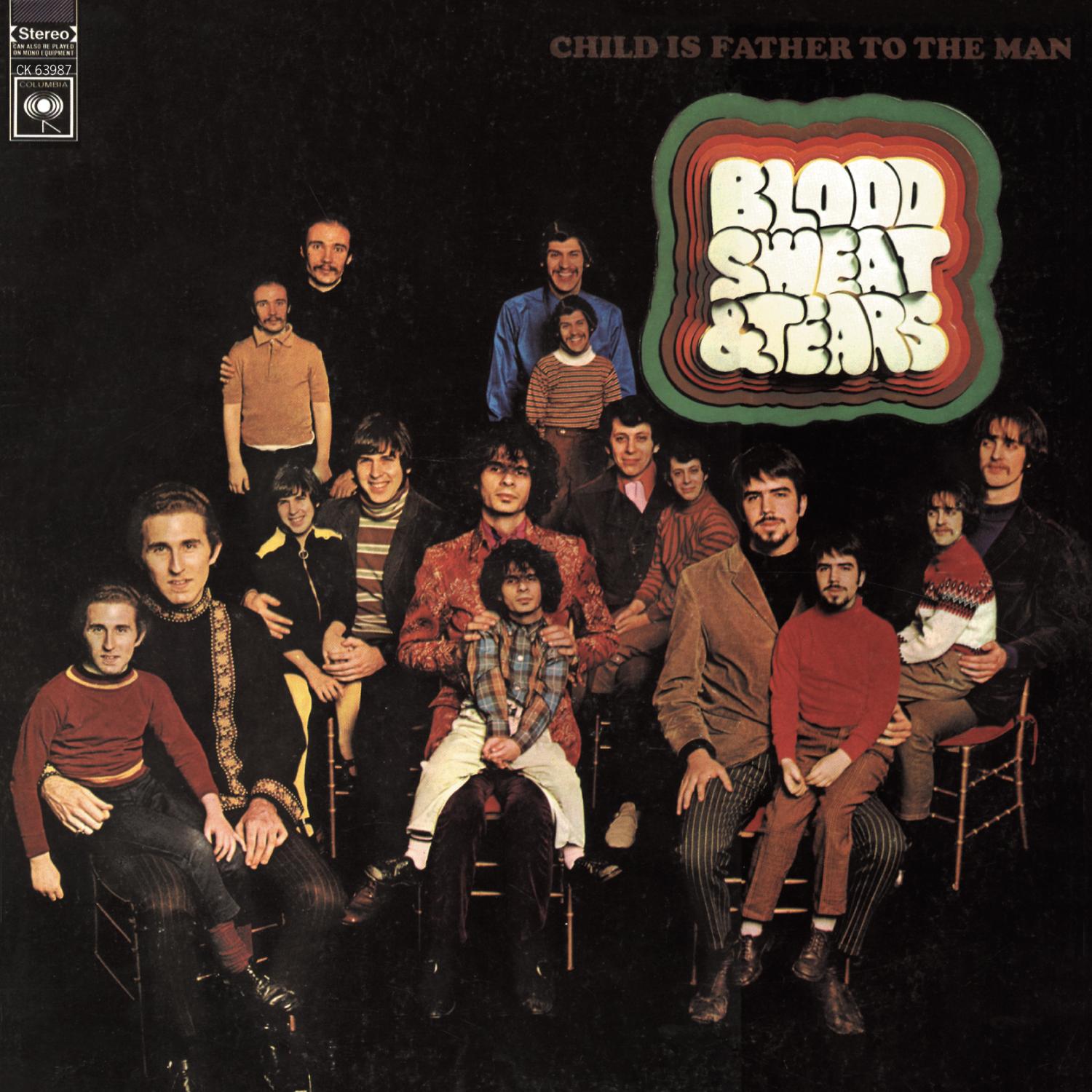

The epochal and musical genre-breaking Al Kooper-led Blood, Sweat & Tears 1968 debut album Child Is the Father to the Man was released on February 21, 1968.

When KPPC-FM in Pasadena, California first spun the disc I quickly bicycled over to Wallichs Music City in Hollywood to get a copy.

In September of 1967 I witnessed trumpeter Hugh Masekela cutting his live Hugh Masekela is Alive and Well at the Whisky album.

In May 1968 KHJ radio introduced Hugh Masekela’s “Grazing in the Grass,” recorded at Gold Star studios, and immediately a smash hit on the UNI Records label helmed by visionary A&R man, Russ Regan.

All through the sixties decade, Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass were regularly in rotation on the AM radio dial and selling albums and doing concert tours.

Horn players Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Pharoah Sanders, Maynard Ferguson, Don Ellis, Buddy Collette, Charles Lloyd, and Eric Dolphy in 1967 were garnering airplay and exposure on jazz and nascent FM rock underground radio stations.

The groundwork for horn rock or jazz rock, as it was now being heralded, had been forged by the Chess, Motown and Stax record labels and hit singles from the Buckinghams on Columbia Records.

In addition, a retail climate and receptive music press existed for BS&T’s Child is the Father to the Man sonic expedition in February 1968.

Keyboardist Ray Manzarek talked about all the Doors seeing Al’s new band at the time, Blood, Sweat & Tears in ‘68 at The Café Au Go-Go in New York, “and it was probably the best use of horns we’d ever seen up to that point in rock and roll or since then. He captured the essence of the four horns with guitar, bass, drums and keyboard absolutely superbly. I play at the end of my piano solo on ‘L.A. Woman,’ my homage and tip of the hat to Al Kooper. I play a musical quote from ‘House in the Country.’”

Born in Brooklyn, New York in 1944, and raised in Queens, Al Kooper’s musical and recording career has reached 60 years, starting with the Royal Teens of “Short Shorts” fame in 1958.

During Kooper’s career his songs were covered by Pat Boone, Bobby Vee, Keely Smith, Roger McGuinn, Rufus, Gene Pitney, Tommy Sands, Freddie Cannon, the Modern Folk Quartet, Eddie Hodges, Donny Hathaway, Betty Wright, the Staple Singers, Ten Years After, Carmen MacRae, and crafting such memorable tunes as “I Must be Seeing Things” for Gene Pitney. Al is one of the co-writers of Gary Lewis and the Playboys’ “This Diamond Ring.”

Kooper founded the Blues Project, started (and quit) Blood, Sweat & Tears after one LP. He worked as a Columbia A&R staff producer, dreaming up the Super Session and Live Adventures concepts.

Al’s name can be found on tracks and album credits by everyone from Judy Collins and Joan Baez, to Phil Ochs and Peter, Paul & Mary, Tom Rush, Paul Butterfield, and Eric Andersen.

His keyboard work graces Simon & Garfunkel’s Parsley, Sage, Rosemary And Thyme, Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde, The Who Sell Out, the Jimi Hendrix Experience’s Electric Ladyland, the Rolling Stones’ Let It Bleed, Taj Mahal’s Natch’l Blues, and B.B. King’s Live And Well.

In 1998, Kooper also published his revealing and educational autobiography Backstage Passes and Backstabbing Bastards: Memoirs of a Rock ‘N’ Roll Survivor. Mandatory reading.

“In 1968, Al Kooper released two albums that reflected opposite poles of his nature. Child Is Father to the Man by Blood, Sweat & Tears, the big horn band he started, used the studio as an instrument, while Super Session featured Al, Mike Bloomfield and Stephen Stills mostly just jamming,” recalls musician and writer Michael Simmons.

“In 1968, Al Kooper released two albums that reflected opposite poles of his nature. Child Is Father to the Man by Blood, Sweat & Tears, the big horn band he started, used the studio as an instrument, while Super Session featured Al, Mike Bloomfield and Stephen Stills mostly just jamming,” recalls musician and writer Michael Simmons.

“Both recordings set templates for the range of his future work and established his refusal to be diminished by the constricts of rules or genres,” Simmons continues. “Al’s up for trying anything that piques his interest — his only allegiance is to quality. Along with the Beatles, Brian Wilson and the Motown masters, he’s one of the top mad scientists of rock ’n’ roll.”

In 2007 I conducted an interview with Kooper when the 40th anniversary edition of Child Is the Father to the Man was issued by the Sony Music/Legacy label.

HK: How did you get the idea or concept of putting brass instruments in to rock and roll that gave us Blood, Sweat & Tears? Was it during the Maynard Ferguson on Roulette Records period that blew your mind?

AK: Yeah. That was an immediate transference. I just said, ‘man, would I love to have a band that could, and I remember the exact words, that could put dents in your shirt from 15 yards.’

They just blew…It was just the most amazing thing I ever saw. It wasn’t like Count Basie or Duke Ellington. It was like modern…almost rock ‘n’ roll. It was fantastic. It was an incredible experience. I was sort of like a groupie. I knew some of the guys in the band and they treated me nicely. I was only about 15 and it was just fantastic. I turned 20 when it was over and Maynard left the country. So I spent from 1959 to 1964 really every time they were in the area of New York I went to the gig. I hung out. I was friends with the drummer. People were nice to me.

“In New York in those years Birdland was a big deal and one of the great things about Birdland was the best seats in the place were for underage people. They were just to the left side of the stage. And they were the best seats in the house. So, you had to be 18 to drink, but somehow, probably because the mob owned it, you could go in anytime. They let underage people in which was fantastic anyway, just in principal. But not only could you come in but you had the best seats in the place. So, that was not wasted on me.

Q. You met bass player Jim Fielder at the 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival, who was playing with Buffalo Springfield at that event and invited him to be in Blood, Sweat & Tears.

A. I was the assistant stage manager at the festival. Two things came out of Monterey. Jim Fielder. I knew him because of Tim Buckley and Mothers of Invention. These are things that first took place in New York. When I went out to L.A., I was looking for musicians for my new band. I bumped into him and ran it by him. He procured a drummer, Sandy Konikoff, and we played together.

“Directly after Monterey, I went to the Big Sur Folk Festival on the grounds of the Esalen Institute and played with Sandy and Jim. We performed some of my new songs—“I Can’t Quit Her” and “My Days Are Numbered.” Then, the Blood, Sweat and Tears album, Child Is the Father to the Man.

“I came to Columbia Records in 1967, after the June Monterey International Pop Festival. I assembled BS&T and joined the label as a staff producer. I single-handedly brought BS&T to Columbia.

“I went to Jerry Wexler, Mo Ostin and Bill Gallagher at Columbia, because Clive Davis wasn’t in power yet. And I got turned down by Jerry Wexler and Mo Ostin and Bill Gallagher liked it.

“So I went to follow it up and Bill Gallagher was gone. And so I ended up with Clive. I played it for Clive, ‘Well, what did Bill say?’ ‘That we were going to have a deal.’ And Clive said, ‘I agree with that.’ ‘Oh fabulous. Great.’ And Clive took me to breakfast and we closed the deal.

“After the Monterey International Pop Festival, when Clive took over in late ’67, Clive Davis at Columbia was flying by the seat of his pants. And Leonard Cohen, signed by John Hammond, and then John Simon is the producer.

“As far as Columbia in England they understood what was being done from the label in America in 1967 and ’68. Bookends, Dylan’s John Wesley Harding, Songs of Leonard Cohen, the BS&T album.

“The Rock Machine they called it. That was a result mostly of the English music press and not the domestic label. The label had a real grasp on the music that was being made. FM radio was a factor.

Q. What did you learn from John Simon as a producer who did your BS&T LP?

A. In answer to that question, I would honestly have to say everything. I learned how to be a record producer. I mean, if I go in to produce a record it’s really based on what I learned on those sessions from him.

Q. But I know you were active in the music world from 1958-1968 before John Simon, who co-produced produced Songs of Leonard Cohen and Bookends for Simon & Garfunkel and produced Cheap Thrills by Big Brother and the Holding Company entered your action.

A. I know, but John just had it all together. He was perfect. He just couldn’t have been better.

“John Simon. The thing that he did that helped the most the person he chose for the engineer. Fred Catero. When I became a producer there I used that guy whenever I could. When I watched John Simon produced the Blood, Sweat & Tears album I learned everything there was about producing. I didn’t know a fuckin; thing until I watched him work. He was fantastic. And that album could not have been as good as it was without him. The most important thing for me was he understood how deep my involvement was in terms of writing the songs and singing the songs, arranging the songs. And he worked with me.

“He didn’t work with the band. And we made that record together. To the point where I brought that ‘Modern Adventures of Plato’ when I brought that in the band, under the direction of Bobby Columby refused to record that song. And we had a big fight at my house. And then there was a band meeting the next day. And he stupidly let it be decided by John Simon whether we recorded the song. And John said, ‘Not only should we do this song I’ll write the string arrangement.’

“This is the telling moment in the whole thing. I went to visit Paul Simon, as you know I sort of grew up with Paul. So I went to visit Simon and Garfunkel at the Bookends session, and John said to me, ‘What are you doing?’ ‘Well, I’ve written a bunch of songs that are screaming to me to have horns on them.’

“On a break I played him a couple of things. Maybe ‘I Can’t Quit Her’ and maybe ‘I Love You (More That You’ll Ever Know.’

“And I said ‘I had to leave the Blues Project because they wouldn’t let me have horns on the songs. The songs are screaming, ‘we want horns.’ So he said, ‘Well, if you get a deal let me know. Those are great songs. I’d like to be involved them.’ ‘Really?’ ‘Yeah!’ And that’s what happened. And he had an understanding of the singer songwriter.

“He was an erudite musician. And that was the important thing. That was the thing I learned from him. How to use that in the production of the record. And I couldn’t have made that record without him.

“When we did ‘Without Her’ I didn’t even think twice about, ‘you should play piano on this.’ He said, ‘you don’t want to play piano?’ ‘No I do but you can play this much better than me.’ And he did and he’s credited for it. There was no question in my mind he could do what I couldn’t do.

“We made Child is the Father to the Man in three weeks from start to finish. However, we were very rehearsed. But the first thing did was he took us in the studio and he said, ‘play every song you are considering recording.’ And he recorded it, I think in mono, and he took those tapes and he picked the songs that would be on the album.

Q. You found the Randy Newman tune (“Just One Smile’), (“Without Her”) by Harry Nilsson and Tim Buckley’s “Morning Glory.”

A. Well, first of all, Randy Newman and I wrote for the same publisher, January Music, and I played on a version of ‘Just One Smile’ (Gene Pitney), and so I knew the song very well. And I knew all of Randy’s songs by the demos I’d get up at the publisher. I knew Randy Newman way before you did, or anybody did. And I never met him but the demos were so wacky, it was just compelling, because his voice was so strange, and the whole conception was so strange. I just was really floored by it. So, I always wanted to do that song. So that was my chance.

Q. “Without Her” from Harry Nilsson?

A. At the time that we did the album that was my obsessive song, ‘Without Her.’ His version. I played it all the time. I could not get sick of it. It was incredible. And I wanted to record it and so I had to write another arrangement because, you know, ‘cause his was fantastic. So I made it in to a bossa nova.

Q. And what about “Morning Glory” from Tim Buckley?

A. That was just a question of finding a song for (guitarist) Steve (Katz) to sing, so I suggested that to Steve and he bought it.

Q. It seems like you were playing team ball.

A. I might disagree with you. When I started with the band, I said listen, ‘I have this idea. I know what to do. I said you guys just got to let me do it.’ They said, ‘Yeah Al. Right on, we’re with you. Yes Al.’ Like that. And then, you know, all of a sudden, they were saying, ‘get lost.’

“So, I really stink at politics. So my thing was I was just in to the music and I just wanted to do the music, I knew what to do, just leave me the fuck alone and let me do what it is that I do. And they couldn’t do that. They really couldn’t do that and so it became very unpleasant for me and I walked. They made it unpleasant for me and I walked with no regrets.

“Because I had had similar problems with the Blues Project and I just said to myself ‘this is not what you should do. You should not be in bands because there’s a problem.’ And so that was it.

“Now the good part is that it helped me tremendously as a record producer when I worked with bands to understand how a band worked, because I already knew, because I had been in two really horrible situations and it helped me tremendously to understand how to deal with bands when I was producing them. So it was not a wasted bad thing. I learned from it and used it for good.

“So in retrospect it’s OK. Getting out of Blood, Sweat & Tears at that time really preserved my reputation. What they did after that I did not want to be involved with. So everything worked out for the best. They had their thing. And the first thing I did after that was Super Session which was very successful, and it worked out great for both of us.

Q. “I Can’t Quit Her.” Did you always have such a hard percussive piano style?

A. No. I was just really a heavy-handed piano player. That’s what it was.

Q. Where did you write this terrific song?

A. I wrote it in Hollywood at the 9000 Building on Sunset Blvd. in a songwriting office. And I remember I stopped in the middle when I was writing the bridge because I came up with the thing ‘proselytized,’ and I didn’t know what it meant so I had to go find a dictionary in the building and looked it up and it meant exactly what I wanted it to mean. It was serendipitous.

Q. And one of your co-writers on “This Diamond Ring,” Irwin Levine, you co-wrote “I Can’t Quit Her” with.

A. That started as a girl group song, ‘I Can’t Quit Him.’ ‘I Can’t Quit Him. No No No…’ And then it went in to something else that had nothing to do with that. So I wrote a new song that really just had the melody of the title, ‘I Can’t Quit Her,’ which is from ‘I Can’t Quit Him,’ and so I gave him 25 per cent of the song for that. Although he was not there when I wrote it. So that was a moral generosity on my part. I could have just done that and I don’t think there would have been any repercussions. I could have like taken it 100 percent but I felt guilty. So I didn’t do that.

Q. I’ve heard Donny Hathaway covering your tune “I Love You More Than You’ll Ever Know,” and your original is contained your collection Rare and Well Done. Talk to me about the genesis of the tune from the writing, to the demo, and how that specific song came together?

A. I pretty much wrote it about my second wife who I was married to at the time. I wrote it in my apartment on Waverly Place on a piano. It was pretty much musically influenced by the song ‘It’s Man’s World’ by James Brown. And lyrically it was inspired by the song ‘I Love You More Than Words Can Say’ by Otis Redding. So it’s kind of an amalgam of those two songs, neither of which I had the nerve to sing, so I had to write my own.

Q. How did the Donny Hathaway cover happen?

A. I’ll tell you. It’s a great story. Jerry Wexler called me out of the blue, ‘Al I just wanted to tell you I’m recording your song with Donny Hathaway. That Blood, Sweat & Tears song.’ ‘Which one?’ He said, ‘Somethin’ Goin’ On.’ I said, ‘Gee Jerry, that’s great Jerry, I’m a huge fan of Donny’s. That’s fantastic.’ But I said, ‘I think you picked the wrong song.’ He said, ‘what do you mean? Donny loves it.’ I said ‘you need to go back to that record and listen to ‘I Love You More Than You’ll Ever Know.’ ‘I don’t know Al…’ ‘Just go ahead and do it.’

“He called me back about two weeks later. ‘Al you were right. We’re gonna do that.’ I said, ‘you wouldn’t do both would you? He said, ‘Shut up, Al.’ (laughs). The story is not over. ‘I’ll send you a cassette when it’s done.’ ‘Thank you Jerry, and thanks for listening to me.’

“So, about two months later a cassette comes. Now, when I wrote that song there was one line in it that I never sang until the recording session, for a number of reasons. One of which is I just prayed someday a black person would sing it and that the line would mean so much more, which was ‘I could be President of General Motors.’ It didn’t really make as much sense for a white person to sing that because a white person could be President of General Motors.

“So I get the thing, and I’ve waited all this time, like six years or something, for a black person to sing this song so I could hear this line sung by a black person. And I’m listening to the record, and he’s killing it, he’s just doing a fantastic job, and changed a lot of things in it. He changed the melody, he changed the chords, but it’s killing me. I’m liking it. And then it comes to that line and they change the fuckin’ words, to like a really lame line, too. ‘I could be king of everything.’ So, I stop the tape and I call Jerry Wexler and I’m fuckin’ furious.

“And I say ‘Jerry Wexler please.’ ‘Who is calling?’ ‘Al Kooper.’ ‘Hey Al, did you get that cassette I sent you?’ ‘I said yeah. Why did you change the words to the song?’ ‘What are you talking about?’ I said, ‘I could be President of General Motors.’ He said, ‘Al, a black person could never be President of General Motors.’ I said, ‘you’re such a fuckin’ asshole.’ And I hung up and I didn’t talk to him for 25 years.

Q. “My Days Are Numbered” is a stirring song on the first BS&T LP. Lovely tune.

A. Well you know, there’s a really good cover of it on my solo album Soul Of A Man. Actually, I even like it better than the original. It’s a live version from The Bottom Line in New York.

Q. Did you originally bring it in as a demo and do it with BS&T?

A. These songs were all, with the exception of ‘The Modern Adventures of Plato, Diogenes, and Freud’ which I wrote during the session, all these songs were written and they were the reason why I formed the band because I had this group of songs that needed horns.

“I’m really not happy with the vocals on them. Really not happy with the vocals on that. The singing at that point in my career was my weakest card and it hurts me to hear my singing until about maybe five years ago. It’s tough for me. I’m very self-critical. I have found now that there is so much time it takes me 10 to 15 years to listen to an album again after I’m done with the initial work and all that. So that’s another thing.

Harvey Kubernik is the author of 14 books, including heralded titles on Leonard Cohen and Neil Young. His 2017 volume, the acclaimed 1967 A Complete Rock History of the Summer of Love was published by Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

His literary music anthology Inside Cave Hollywood: The Harvey Kubernik Music InnerViews and InterViews Collection, Vol. 1 was published in late December 2017, by Cave Hollywood.

Kubernik’s multi-voice narrative book The Doors Summer’s Gone was published by Other Cottage Industries in late March 2018.

Over his 45 year music and pop culture journalism endeavors, Harvey Kubernik has been published domestically and internationally in The Hollywood Press, The Los Angeles Free Press, Melody Maker, Crawdaddy, Variety, The Hollywood Reporter, MOJO, Shindig!, HITS, The Los Angeles Times, Ugly Things, Record Collector News and www.cavehollywood.com