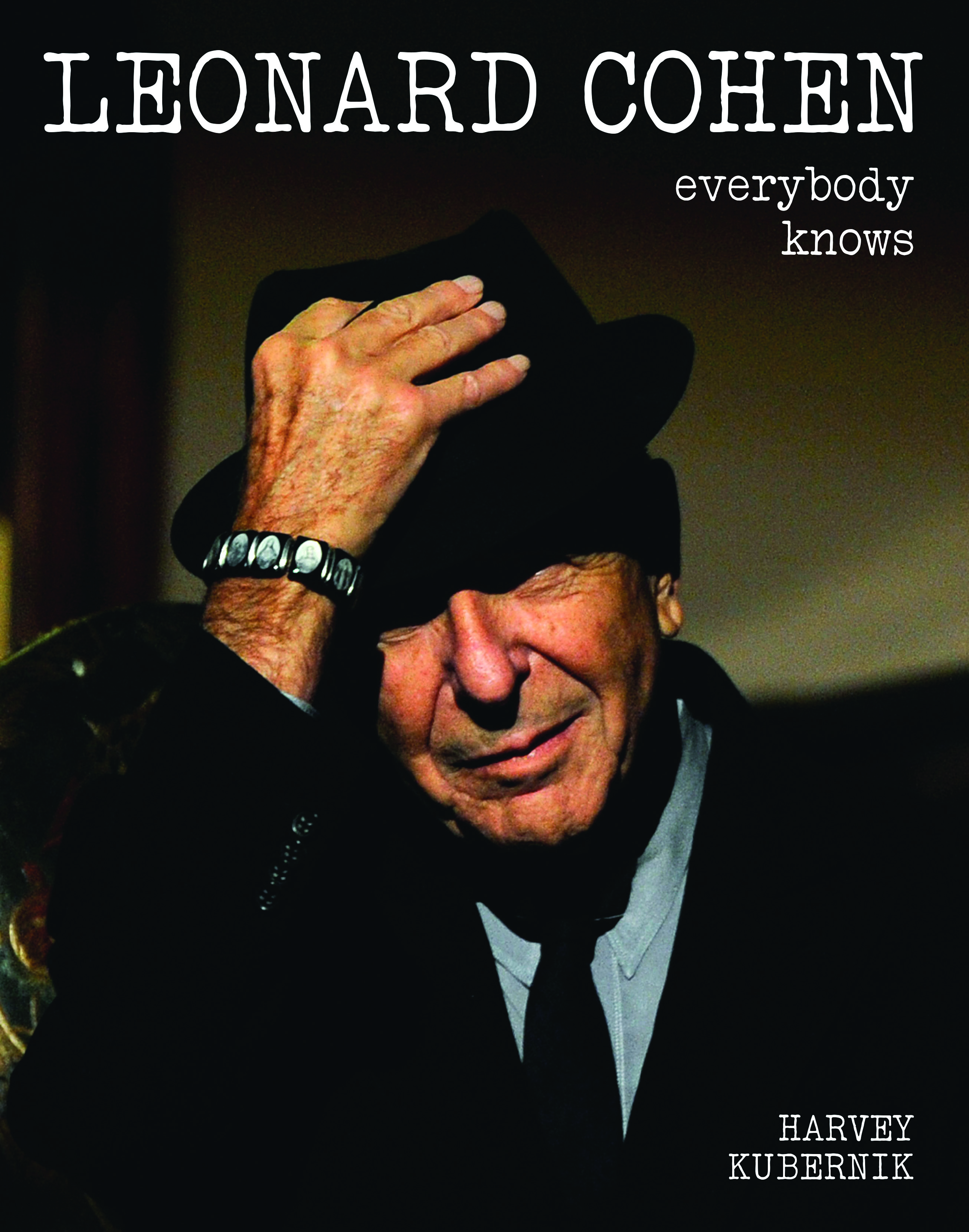

Author and rock music historian Harvey Kubernik is our resident wordsmith and pop culture chronicler at www.cavehollywood.com

Two years ago Harvey penned a critically acclaimed book on Leonard Cohen, Everybody Knows. It traces the artistic journey of Cohen the young poet and author in his home town of Montreal and ending with his 2012 release – Old Ideas – and recent awe-inspiring live performances.

On the very recent physical passing of Leonard Cohen, we thought it was appropriate to ask Harvey to give us a sense of Cohen’s life and work.

He sent us two interviews he conducted with Leonard for the now defunct Melody Maker from over 40 years ago-long before Leonard’s commercial renaissance this century.

Harvey Kubernik was there when it really counted…

Leonard Cohen: Cohen’s New Skin

Harvey Kubernik, Melody Maker, 1 March 1975

LOS ANGELES: “For a while, I didn’t think there was going to be another album. I pretty well felt that I was washed up as a songwriter because it  wasn’t coming anymore.

wasn’t coming anymore.

“Actually, I should have known better, it takes me a long time to compose a song,” reflected songwriter/poet/performer Leonard Cohen in between sets of a sell-out engagement at Los Angeles’ Troubadour club.

Over the last few years, Cohen has been enigmatic in public, attempting to shy away from interviews and only leaving his music and poetry to speak for himself. However, in the warm environment of Southern California, he had a change of heart and decided to talk to the press and reveal the true side of his personality.

“I used to be petrified with the idea of going on the road and presenting my work. I often felt that the risks of humiliation were too wide. But with the help of my last producer, Bob Johnston, I gained the self-confidence I felt was necessary. My music now is much more highly refined.

“When you are again in touch with yourself and you feel a certain sense of health, you feel somehow that the prison bars are lifted, and you start hearing new possibilities in your work. The previous album Live Songs represented a very confused and directionless time. The thing I like about it is that it documents this phase very clearly. I’m very interested in documentation and often feel that I want to produce a whole body of work that will cover a wide range of topics and themes.

“Not necessarily personal reflections, but a sort of look at the last two decades. My first book was published at 20, and that was 20 years ago.”

Since Cohen is a perfectionist, many have felt that he compromised his artistry by moving into music to reach a broader base of people than his books. Leonard looks at it differently.

“I don’t have any reservations about anything I do. I always played music. When I was 17, I was in a country music group called the Buckskin Boys. Writing came later, after music. I put my guitar away for a few years, but I always made up songs. I never wanted my work to get too far away from music.

In America, Cohen still remains a cultist figure, with fans lining up for hours and hours in advance of ticket sales. But still his audience is a mere fraction compared with the kind of widespread appeal that he’s enjoying throughout Europe and Great Britain. “I have occasionally thought about the differences in my audiences. I think that maybe my music fits into the European tradition.

“America has its own version of the blues. What I do is the European blues. That is, the soul music of that sensibility – White Soul. Even though Europe has its own version of bubblegum.”

In his latest work Cohen has seemed to take on a less personal tone, even though some of the works were started years ago; some are even five years old. “I work very slowly and abandoned hope for many of them. However, last summer I went to Ethiopia looking for a suntan. It rained, including in the Sinai desert, but through this whole period I had my little guitar with me, and it was then I felt the songs emerging – at least, the conclusions that I had been carrying in manuscript form for the last four or five years, from hotel room to hotel room.

“I must say I’m pleased with the album. It’s good. I’m not ashamed of it and am ready to stand by it. Rather than think of it as a masterpiece, I prefer to look at it as a little gem.

“The original cover was a 16th century picture from an alchemical text depicting two angels in an embrace. Columbia felt unclothed angels were too much for the American public. A quarter of a million copies have been sold in Europe with this cover and there was not a single reference made to it. Since I designed it, I finally won the battle with Columbia, and they are reinstating the old album cover with a modesty jacket.

“With the exception of these minor problems, I’ve been very happy with the album and my present tour. I am surprised though to see so many young faces in the audience. Maybe it’s a sign of a growing awareness, and I’m pleased, to say the least, that these individuals are taking an interest in my work.”

Between sets, Leonard was happily interrupted with the appearance of old friends such as Phil Spector and Bob Dylan, who wanted to wish Cohen well during the hectic booking. What does Cohen think of his old heroes and the contemporary music scene today?

“In the early days I was trained as a poet by reading English poets like Lorca and Brecht, and by the invigorating exchange between other writers in Montreal at the time. Now I admire Dylan’s work tremendously, especially the later work. I also like Van Morrison very much, including his superb Veedon Fleece effort. I’m always interested in what Joni Mitchell is doing.”

Much of Cohen’s work deals with such themes as betrayal, dealing with emotional hardships, or the re-establishment of a sense of identity that is fading in this impersonated world. He often seems to like to deal with biblical references whenever possible to add a majestic quality to his tunes.

“My tunes often deal with a moral crisis. I often feel myself a part of such a crisis and try to relate it in song. There’s a line in a poem I wrote that sums this up perfectly: ‘My betrayals are so fresh they still come with explanations.’ As far as the use of Biblical characters in such tunes as ‘Story Of Issac’, and ‘Joan Of Arc’, it was not a matter of choice. These are the books that were placed in my hand when I was developing my literary tastes.”

Another interesting use of Cohen’s music appeared in Robert Altman’s film McCabe And Mrs Miller. “There’s an interesting story regarding that piece of work. Director Robert Altman actually built the film around my music. The music was already written, and when he heard it he wanted to ask me to let him use it. I was in Nashville at the time and had just gone to the movies to see a film called. Brewster McCloud.

“I thought it was a fine movie. That night I was in the studio and received a call from Hollywood. It was from Bob Altman saying he would like to use my music in a film. Quite honestly, I said, ‘I don’t know your work, could you tell me some of the films you’ve done?’ He said Mash, and I said that’s fine, I understand that’s quite popular, but I’m really not familiar with it. Then he said there was a film I’ve probably never seen called Brewster McCloud. I told him I just came out of the movie and thought it was an extraordinary film, use any music of mine.”

© Harvey Kubernik, 1975

Leonard Cohen Melody Maker

Harvey Kubernik, Melody Maker, 6 March 1976

LEONARD COHEN’S GREATEST Hits is an interesting album to contemplate when one remembers that Cohen was in his mid-thirties when he began to make records, and already had a well-established literary reputation behind him. The album is a tribute to the strength of Cohen, who is perhaps popular music’s wierdest schizophrenic: almost a legend throughout Europe and England as a poet/performer/artist, but only minor, if growing, cult figure in the States.

He’s a perfectionist, too. Recently he withdrew a novel from his publishers because he wasn’t happy with it. And this album wouldn’t be available if it was just another thrown-together milestone. Cohen was in Los Angeles for a few days getting loose ends together for future activities and to check out Lewis Furey, an old friend. In Los Angeles, he usually stays at the Chateau Marmont. Tonight we wandered down Sunset Blvd, to the Hyatt House for a chat.

“I was against the idea at first. But I don’t quite remember why I was convinced of it. There’s a new generation of listeners who don’t know a lot of the work. I picked the songs and had total artistic control.”

Included are: ‘Suzanne’, ‘Sisters Of Mercy’, ‘So Long Marianne’, ‘Bird On The Wire’, ‘The Partisan’, ‘Lady Midnight’, ‘Hey, That’s No Way To Say Goodbye’, ‘Famous Blue Raincoat’, ‘Last Year’s Man’, ‘Chelsea Hotel’, ‘Take This Longing’ and ‘Who By Fire’.

“I designed the package and I insisted the lyrics be included, and there are notes on the songs. It’s 12 songs, close to 50 minutes, and apparently they can master a record this way in England.”

Cohen has never been a stranger to music. As early as 1954, he was playing country in a group called the Buckskin Boys. Like Bob Dylan before him and Bruce Springsteen after him, in 1967 he auditioned for John Hammond Sr. who had become aware of his abilities via the Judy Collins cover version of ‘Suzanne’.

“I came to New York and was unaware of what was going on at the time. I had never heard of Phil Ochs, Bob Dylan, Judy Collins or any of these people, and I was delighted, overwhelmed and surprised to discover this very frantic musical activity. Hammond was extremely hospitable and decent. He took me out for lunch at a place called White’s on 23rd Street. It was a very pleasant lunch, and he said, ‘Let’s go back to your hotel room, and maybe you can play me some songs.’ So he sat in a chair and I played him a dozen songs. He seemed happy and said that he had to consult with his colleagues but that he’d like to offer me a contract.”

“My first producer was John Hammond and I didn’t know the ropes at all. We recorded some numbers, and then his wife got sick and he became ill. Then I switched producers to John Simon (later to produce the Band, among others), whom John Hammond suggested. John Simon was great, and much greater than I understood at the time. I put the tracks down with guitar and voice, and used a bass sometimes. He took them and worked on them, and he presented me with the finished record, but I felt there were some eccentricities in his arrangements that I objected to.”

Next came the excellent Songs From A Room. Bob Johnston of Blonde On Blonde fame did the production honours and, like Simon on the first album, and Cohen’s current producer, John Lissauer, the vocals were pushed out-front.

“I liked the work he did with Dylan and we became good friends. Without his support I don’t think I’d ever gain the courage to go and perform. He played harmonica, guitar and organ on tours with me. He’s a great friend and a great support. We worked hard on the albums we did together, but I wasn’t totally happy. Overall I couldn’t find the tone I wanted. There were some nice things, though,” he adds.

Songs Of Love And Hate was the third album, produced again by Johnston and recorded in Nashville Hand Trident Studios in London. The strings and horns were arranged and conducted by Paul Buckmaster. However, again he wasn’t throughly pleased. Looking back he says, “with each record I became progressively discouraged, although I was improving as a performer.”

A live album was released in 1973, and it wasn’t till late in 1974 that New Skin For The Old Ceremony was issued.

“I heard John Lissauer playing in a club in Montreal with Lewis (Furey). John and I started talking and I played him a bunch of songs, almost half-finished.”

“Lissauer has the deepest understanding of my music. I had finished most of the songs that previous summer, got the group together and toured the US for the last year.”

“Now I’ve entered into another phase, which is very new for me. That is, I began to collaborate with John on songs, which is something that I never expected, or intended, to do with anyone. It wasn’t a matter of improvement, it was a matter of sharing the conception, with another man.”