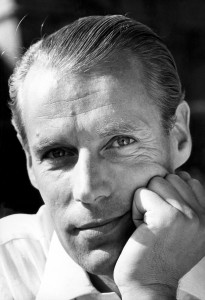

George Martin

a grand soul.

He will be missed.

He knew how

to make the music come alive

and touch the soul

he gave breath

and depth

to notes and words.

He helped create

musical masterworks.

He made a huge impact

on so many lives.

I met him a few times

and he was humble

and kind

and we talked touch

about putting music to words

or words to music.

He was an inspiration

and will continue

to inspire.

The Sufi Poets say

All is music

and found music

is found

in all things

and George brought that to this planet

in our time

perhaps as much

as anyone ever did.

Stephen John Kalinich

Record producer Sir George Martin, known as the “fifth Beatles,” has died at age 90. His family issued a statement and thanked “everyone for their thoughts, prayers and messages of support” after his death at home on Tuesday, his manager said.

Ringo Starr on his Twitter account revealed the news and stated, “Sir George “will be missed.”

It was Martin who signed the signed the Beatles and produced more than 700 records, including studio efforts with Cilla Black, the Goon Show, and Gerry and the Pacemakers.

Sir Paul McCartney on his website issued a statement about Martin. “

“I have so many wonderful memories of this great man that will be with me forever. He was a true gentleman and like a second father to me. He guided the career of The Beatles with such skill and good humour that he became a true friend to me and my family. If anyone earned the title of the fifth Beatle it was George.

“From the day that he gave The Beatles our first recording contract, to the last time I saw him, he was the most generous, intelligent and musical person I’ve ever had the pleasure to know.”

“Perhaps the greatest of George Martin’s so many achievements,” insists Gary Pig Gold, “was his not only agreeing to even listen to Lennon and McCartney’s original material in 1962, but then recording and releasing it …without adding his name to the songwriting credits! He absolutely wasn’t acting like ANY other British record producer at the time, and the entire world has been made to sound a lot better because of it. To say the least.”

Over the decades I had some encounters with Sir George Martin as well as engineers and producers who worked with him. I thought it was appropriate to share my trip with Cave Hollywood viewers.

In 1976 I was introduced to George Martin at the opening of the Chrysalis Records office in West Hollywood on Sunset Blvd. We didn’t talk about the Beatles. Mr. Martin spoke about his production of Jeff Beck’s Blow by Blow at the reception.

Near the end of the last century I had another conversation one evening with Sir George Martin after he had faxed me on his letterhead a wonderful note lauding my production of a Ray Manzarek spoken word album.

We met at the Hollywood Bowl the next time he was in Los Angeles when his office invited me to Martin’s sound check for a recital he was conducing and narrating of Beatles songs at the legendary venue. “The group did a lot of quality material,” he quipped around a rehearsal break that sunny afternoon.

A handful of years ago, I connected again with Martin and his son Giles at the landmark Capitol Records building inside their renowned Studio B. It was a media gathering and playback unveiling for the Beatles’ LOVE album that day.

LOVE, the latest Cirque du Soleil creation, a co-production with Apple Corps Ltd., celebrates and respects the musical legacy of The Beatles and is presented exclusively at The Mirage in Las Vegas.

The LOVE project was born out of a personal friendship and mutual admiration between the late George Harrison and Cirque du Soleil founder Guy Laliberté.

As Music Director for LOVE, Giles Martin is at the epicenter of a revolution in the musical legacy of the Beatles while working side-by-side with his father, Sir George Martin.

“Our first mission was to try and achieve the same intimacy we get when listening to the master tapes at Abbey Road Studios,” volunteered Giles. “The last thing we wanted to create was a retrospective or a tribute show. The Beatles, above all else, were a great rock band. With the manipulation of the tracks and the huge number of speakers in the theatre, the audience will feel as though they are actually in the room with the boys.

“All the Beatles were very encouraging. After the initial demo thing they made me feel part of the process. With both Ringo and Paul, my main memory, my biggest fondest moment, of the whole thing, was nothing to do with me, both Paul and Ringo said to me that I had been so sensitive with our material and really taken it in, and that means a great deal, but the thing that struck me was at Abbey Road was listening to ‘Come Together’ with them both and individually, they weren’t together at the time, ‘God, we were really good on this day. I remember this day. We really nailed this.’”

“We wanted to make sure there are enough good, solid hit songs in the show, but we don’t want it to be a catalog of ‘best of’s’,” reinforced Sir George Martin. “We also wanted to put in some interesting and not well-known Beatles music and use fragments of songs. The show is a unique and magical experience.”

“George and Giles did such a great job combining these tracks. It’s really powerful for me and I even heard things I’d forgotten we’d recorded.” commented Ringo Starr.

“This album puts the Beatles back together again, because suddenly there’s John and George with me and Ringo,” said Paul McCartney. “It’s kind of magical.”

Inside the Capitol facility, Sir George and I talked briefly about a Frank Sinatra recording session he had attended in this very same room on his first visit to Hollywood, California in 1958. The EMI label sent him over the pond after Martin was invited by Capitol executive Voyle Gilmore to visit the famed Tower.

Martin described that date when Sinatra was backed by Billy May’s orchestra while actress Lauren Bacall was in attendance. The songs cut were eventually placed on Sinatra’s Come Fly With Me LP.

I had met all the members of the Beatles as a reporter and author and now wanted to make it a point to personally thank George Martin for discovering and signing the Beatles to their British record label deal in the first place. And to praise his persistent determination, along with Brian Epstein, encouraging Capitol Records to have some faith domestically in Martin’s groundbreaking Parlophone/EMI recordings with the band back in 1963.

It was at my most recent Martin encounter, where one of his Beatles’ productions started playing in studio B. Try hearing their music over custom TAD monitors.

George then autographed a solo album, put his arm around me and enthused, “Pretty good stuff. Don’t you think?”

In 2012 engineer/producer Ken Scott published a memoir, written with Bobby Owsinski, Abbey Road To Ziggy Stardust. In the book, Scott, who worked under George Martin, confessed about the first time he was in the control room with the Beatles in 1964.

He was booking tapes at the EMI studio library. Ken actually held the 4-track master tape of ‘Can’t Buy Me Love” when it was being prepared as the next Beatles single.

He subsequently attended the “I Should Have Known Better,” courtesy of engineer Norman Smith, and handclapped with Ringo and Paul for a take that wasn’t used.

Scott’s first day as a button pusher was on June 1, 1964 during sessions for A Hard Day’s Night. Songs not utilized in the film like “I’ll Cry Instead,” “I’ll Be Back” as well as “Matchbox” and “Slow Down.”

Eventually Ken worked on Help! and Rubber Soul, before engineering the White album.

Did Beatles’ engineer Ken Scott have any ideas why we were talking about the Beatles’ catalogue, 50 years on?

“Because of the changes going on in that period of time their music and they have become more important. They were very much a part of the major change within the western civilization. A lot of it stemming from the second World War. Because of the baby boom. Younger people were getting more of a say. More power. And that helped to change things, which they were a major part of.

“I also feel that a lot of it is because it’s real. They were performances. It’s not like it is today where it’s all pieced together. Yes, we would do punch-ins and that kind of thing, but there wasn’t copying one chorus and putting it in every chorus so it’s always exactly the same. They had to sing and play everything. And they had this ability, which so few other acts had, the closest I would probably come is U2, but they had this ability of being able to take the audience, their audience through changes. Without losing them. They always moved just enough that they could pull their audience with them and have the audience grow along with them.”

Scott has also watched the Beatles move from vinyl to cassettes to CD format.

“To me it’s analog vinyl to CD. I find digital quite often cold compared to analog. There’s a warmth and a depth if you like to analog, be it vinyl be it tape that we don’t get in the digital domain. We will eventually, but we’re not quite there yet. The whole point for me was that we had to move away from vinyl, at least for pop music, because the vinyl that was being used for albums was becoming so bad and so noisy that records were becoming thinner and thinner. It had to change. The way we listen to music had to change. And CD’s, even as bad as they were, when they first came out, were better than the quality of the vinyl at that point. I think now there’s probably more the availability of vinyl has improved so the vinyl being used for the records is at a higher standard.”

The one thing that astonishes me about the 50 year recording career of the Beatles on the EMI label, is that all this early work, well at least in 1963, was done without advocates, label support, and only faint music publishing interest from inception, under such skepticism and lack of any faith in the lads.

“You’ve got this band that comes in. They have a moderate amount of success with a single which contains two of their songs and they’re signed to the EMI publishing company Ardmore Beechwood. They are going to do a second single and the publishing company is asked, ‘So, do you want to sign them for publishing on the next single?’ And they turned them down. A complete lack of belief. The way I heard it, this is memory, and second or third hand, my understanding was that George (Martin) had to persuade Dick James to even sign them for publishing.

“George knew Dick from a 1956 single of ‘Robin Hood’ he cut with him that Dick sang. Then he got into publishing. When George approached Dick about working with the Beatles, the way heard it, Dick was at that moment even considering leaving the publishing business. George said to him, ‘Look, I’ve got this band and Ardmore Beechwood has passed. Why don’t you sign them?’ ‘Oh, I don’t know…’ ‘Look, what have you got to lose? We’re going to do a single. Sign them and see what happens.’ And the rest is history. So there was a total lack of belief in anything that they were doing in the beginning.

“I just received an award from him. The Sound Fellowship of the United Kingdom’s Association of Professional Recording Services (APRS). The man who first kicked me out of the control room at age 16. Absolutely astounding moment.

“Walking in his footsteps to a point and realizing. I think it first started to change when I heard David (Bowie) had called me ‘his George Martin’ on the BBC in England. And my first thing was ‘I don’t know if I like that.’ Then when I started to think thru it I realized how much I had taken from George and just that whole thing of allowing the artistic freedom. And you’re there to give advice. To control if you have to but don’t overdue that control.”

“America and Hollywood in late 1963 was dealing with the loss of John F. Kennedy,” offered the late record producer and songwriter Kim Fowley.

“When the Beatles took over the charts and AM radio playlists, locally and nationally, I was a guy who had three hit records already.

“All during 1963 a lot of regional labels passed on the Beatles. The Hollywood and L.A. record companies still had a shirt and tie vibe. They really didn’t want to let foreigners into their offices,” he laments.

“Capitol Records went back to 1942. It was Capitol Records Distribution Company. Glenn Wallichs, songwriter Johnny Mercer, and Buddy DeSylva. Mercer had hits already in ’42—‘Skylark’ and ‘I Remember You.’ DeSylva was a songwriter and a production chief at Paramount Pictures, and Wallichs was the founder of Wallichs Music City in 1940, on Sunset and Vine in Hollywood. Wallichs got the newly-formed label distribution hustle together. Bandleader Freddie Slack and his orchestra, featuring vocalist Ella Mae Morse, recorded ‘Cow Cow Boogie’ in May of 1942 and was the label’s first million seller.

“Then in 1964 I was at Dick James Music office in England hustling. They were the Beatles’ original music publishers via Northern Songs. Here come the four Beatles in suits with the neck ties and Brian Epstein their manager ran in and said, ‘everybody stand up and applaud the boys.’ And they walked in the door,” recalls Kim.

“I met Ringo on two different occasions. Once in 1964 at the Ad Lib Club when I was introduced to him as the co-producer and co-publisher of ‘Alley Oop’ by the Hollywood Argyles. He told me that the Beatles recorded my tune ‘Alley Oop’ at Abbey Road. They did it but it was never mixed down or issued. But it’s in the vaults at the studio.

“It was in 1964 when Murray Deutch of the music division from United Artists Records came in who didn’t care about the Beatles’ movie A Hard Day’s Night, they just wanted the soundtrack override. That’s what he said to me. Murray had worked with Buddy Holly and now had the James Bond franchise. Mike Stewart of United Artists Records in America got the rights domestically, even though as you know, the Beatles were on Capitol Records.

“A Hard Day’s Night was a big important moment in the development and the evolution of the rock song in film and the movie soundtrack as a retail item and stand-alone product itself.

“In 1966 at the Ad Lib Paul McCartney was there, disguised and dressed as an Arab and walking around. I also met him at a party he politely crashed in St. John’s Wood down the street from him. Paul saw a bunch of cars parked and he dropped in to take a look, jumped back in his own car and split.

“Also in 1966, I spent some time with John and Paul in London. Bruce Johnston of the Beach Boys was in town doing advance publicity for the Beach

Boys’ Pet Sounds and had an acetate pressing with him. I was asked to bring the Who’s Keith Moon over who brought John and Paul to the hotel room. They were both very impressed by the recording, left the hotel and went into the recording studio the next day and did ‘Here, There and Everywhere’ for Revolver. The both of them were able to digest and gauge the whole essence of Pet Sounds in one listening.

“I did meet Brian Epstein once time. It was in an underground garage at a hotel after a party and cars were being brought around. I said, ‘what is the secret of the Beatles success?’ And he replied, ‘surround your phenomena with specialists.’ It’s a line in my book, A Cellar Full of Noise. Why don’t you buy it and read it?’

“George Martin was the catalyst for the embryonic dreams of Lennon, McCartney, Starkey and Harrison. Martin was able to consolidate and expand their anticipation. He was a great editor.”

Allan Rouse is the Project Coordinator of this monumental The Beatles in Mono undertaking.

Rouse joined EMI straight from school in 1971 at their Manchester Square head office, working as an assistant engineer in the demo studio. During this time he frequently worked with legendary Norman (Hurricane) Smith.

In 1991, Rouse had his first involvement with The Beatles, copying all of their master tapes (mono, stereo, 4-track and 8-track) to digital tape as a safety backup.

That gig was followed by four years working with Sir George Martin as assistant and project coordinator on the TV documentary The Making of Sgt. Pepper’s and the CDs Live at the BBC and The Anthology.

Further projects followed, including The Beatles Anthology, The First U.S. Visit and “Help! DVD and the albums Let It Be…Naked and LOVE along with George Harrison’s Concert for Bangladesh DVD and album. For a number of years now, Allan has worked exclusively on Beatles and related projects.

I interviewed Allan Rouse from the U.K. at Abbey Road.

Q: Can you discuss working with Sir George Martin as his assistant and project coordinator on the TV documentary The Making of Sgt. Pepper and Live at the BBC. After being involved in the new Beatles’ digitally remastered releases is there even one more thing you learned or respected even more about what Sir George Martin contributed and brought into the sound of the Beatles’ recordings?

A: Having managed to get a job at Abbey Road Studios and working on many sessions as a tape-op then eventually engineer, I thought that the closest I was ever going to get to a Beatles experience was being able to work in Studio Two. However, to sit in my room many years later with George Martin researching the Beatles’ four track tapes for Sgt. Pepper’s was as good as it gets. At the end of that job I had no idea that I was going to work with George again and with the Live at the BBC I ended up spending many more months with him.

“I think everybody learned a lot from each other during the sessions. It was a perfect combination of group, producer and engineers, but George’s previous musical experiences brought something different to The Beatles’ arrangements and productions that made them unique from other groups at the time.

“I have had the good fortune of working on a number of projects in recent years that have involved re-mixing to stereo and 5.1 surround with remarkable results by engineers Peter Cobbin, Paul Hicks and Guy Massey. But, I still have the utmost admiration for the sound that the Beatles, Sir George Martin, engineers Norman Smith, Geoff Emerick, Ken Scott, Phil McDonald and Glyn Johns managed to achieve in the sixties with recording technology in its infancy.

Musician and songwriter/performer, the late Doug Fieger, was Chief Knack member, whose band was best known for their number one smash, “My Sharona,” on the Capitol label.

“The Beatles were unique. They had a unique harmonic structure. It was joyous. And it was good,” he said last decade.

“They did whatever was necessary because of the limited amount of tracks. And they always, almost had all four of them playing at once. So, they were performances of each part of the song. So it wasn’t just tracking and overdubbing. Because of the way they had to record. So all four of them would get an assignment. A shaker, a maraca or percussion track.

“‘How do you get a Beatles’ sound?’ People ask me all the time,” ruminated Fieger. “Earlier in the decade we encored with ‘A Hard Day’s Night.’ Well I say, for the early Beatles’ sound, you get flat wound strings and their fingers. That’s how you get a Beatles’ sound. They used to plug straight into the wall. They didn’t use amplifiers. Everything was being done ‘make it up as you go along and make hits.’

“George Martin brought humor because he was a comedy producer. He did the Goon Show record. He kept it clever and he also brought a musicality and an arrangement sense that they then learned from, obviously. But at the very beginning it was him.

“I think more importantly than sonically, all the studios at the time were treated fairly similarly. That the plainness of the working space contributed much more than the sound.

“If you record a sound well and then you treat it than you have good microphones. EMI made their own custom boards for all the Abbey Road studios in places like India and in Nigeria. The only place that didn’t get them was Capitol Records in the U.S. The record label we were on,” chuckled the proud 12-string Rickenbacker owner.

Harvey Kubernik has been a music journalist for over 44 years and is the author of 8 books. During 2014, Harvey’s Kubernik’s Turn Up the Radio! Rock, Pop, and Roll in Los Angeles 1956–1972 was published by Santa Monica Press.

In September 2014, Palazzo Editions packaged Leonard Cohen: Everybody Knows, a coffee—table—size volume written by Kubernik, currently published in six foreign languages. BackBeat/Hal Leonard Books in the United States.

Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik wrote the text for photographer Guy Webster’s first book for Insight Editions published in November 2014. Big Shots: Rock Legends & Hollywood Icons: Through the Lens of Guy Webster. Introduction by Brian Wilson).

In November of 2015, BackBeat/Hal Leonard in the U.S., Omnibus Press in the U.K. and four other foreign language editions published Harvey’s book on Neil Young, Heart of Gold.