By Harvey Kubernik c 2016

Paul Kantner, a founding member of Jefferson Airplane, died on Thursday, January 28th in San Francisco. He was age 74.

The cause of his physical passing was multiple organ failure brought on by septic shock. Kantner had been plagued with some health problems in recent times, including a heart attack in 2014.

Jefferson Airplane is scheduled to receive a Lifetime Achievement Grammy Award on during the February 15th annual Grammy Awards television broadcast.

“Paul was a key architect in the development of what became known as the San Francisco Sound,” offered Recording Academy President Neil Portnow in a statement released last Thursday.

“The music community has lost a true icon, and we share our deepest condolences with Paul’s family and friends.”

Jefferson Airplane was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1996.

Over the last four decades I interviewed Paul a dozen times, recorded him for a compilation album, produced a spoken word double CD with him. Paul was a delightful and forthcoming interview subject.

Every year or two, I would see fellow Pisces Paul in San Francisco. Usually at his favorite watering hole, Vesuvio’s in North Beach.

In the nineties we would occasionally frequent House of Nanking in Chinatown. Paul later imposed a protest against it, and other eateries, when a no smoking law in San Francisco restaurants was passed. He smoked Camel cigarettes with no filters.

I saw the Jefferson Airplane’s long-awaited 1989 reunion tour at the Greek Theater in Los Angeles and was impressed to re-invest in the band that never became a brand.

One night Paul and I met up and went to Mose Allison perform in Hollywood at the Vine Street Bar & Grill.

I invited Kantner to a recording session I had in Venice with the wonderful engineer/producer, Ethan James, at his Radio Tokyo studios. James, formerly Ralph Kellog in Blue Cheer, shared some bookings with Jefferson Airplane. Kantner brought along some poems to record that I produced.

It was literally the first time in my life two people from San Francisco didn’t constantly complain about Los Angeles. That was refreshing.

I was reminded by a wonderful statement offered by Dr. James Cushing of Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, himself a graduate of U.C. Santa Cruz.

“In Los Angeles all the superficiality is right on the surface and depth is beneath the surface. In San Francisco it’s just the opposite.”

“As far as San Francisco being suspect of L.A. and Hollywood people, we always tried to get above that if possible as a general rule,” Kantner stressed to me. “People didn’t like the Doors. ’Cause they were from L.A. [Laughs.] I rejected the suspicions of L.A. as a general rule. I thoroughly enjoyed L.A. and New York. I could make myself comfortable in either one of those cities. I liked San Francisco a lot.”

In a 2012 interview Paul amplified his regional coastal feelings. “We did the Monterey International Pop Festival in 1967. We did not know what was going to happen, And there was all that L.A. stuff versus San Francisco. It went on. I didn’t pay any attention to it. I enjoyed bands from both towns.

“Again, getting to the heart of the matter. The point is if you find something that makes you joyful, take note of it. Amplify it if you can. Tell other people about it. That’s what San Francisco was about. Both musically, idealistically, and metaphorically and every other way. That’s what we did here. We were in a place that encouraged and nourished that kind of thinking and still does to this day and we took full advantage of it.

“We weren’t up on soap boxes complaining like the Berkeley people. And we need those people too. Those people are very valuable but that’s not what we did.”

“We weren’t up on soap boxes complaining like the Berkeley people. And we need those people too. Those people are very valuable but that’s not what we did.”

The only native San Franciscan in Jefferson Airplane, Paul Lorin Kantner was born March 17, 1941, to Paul S. and Cora Lee (Fortier) Kantner.

He was educated at a Jesuit military boarding school and his lifelong suspicion of authority and protest can surely be traced to that enforced stint in his life. Although he did admit he spent lots of time in the school library where his love for science fiction was birthed. Kantner learned to play guitar as a teenager, got a Pete Seeger instruction book and practiced the banjo.

Paul subsequently enrolled at the University of Santa Clara from 1959-61 and later transferred to San Jose State College in 1961 for a couple of years. He didn’t graduate. He chose to be a musician, gave guitar lessons at a local store and briefly worked at the Cannery packing facility in San Francisco.

In 1962 he encountered another guitarist, Jorma Kaukonen as well as future collaborators, David Freiberg and David Crosby. In 1963, Kantner, Frieberg and Crosby would briefly reside in Venice, Ca. Kantner then embarked on a folk music trek that brought him to San Francisco.

In March 1965, singer, songwriter and guitarist Marty Balin “discovered” singer, songwriter and guitarist Kantner onstage at a San Francisco club, and they decide to form a rock band after talking inside a bar called The Drinking Gourd.

“He was the first guy I picked for the band and he was the first guy who taught me how to roll a joint,” said Balin in a 2016 Facebook posting.

Signe Anderson, a singer who Balin saw at the same club was asked to join. Guitarist Jorma Kaukonen, Kantner’s former college pal, was the next on board. When their first bassist panned out, Jorma phoned Jack Casady, a lifelong friend from the Washington, DC area, who flew west. Similarly, guitarist Skip Spence accepted the challenge to play drums for the first time when the group’s original drummer didn’t work out. After christening the Matrix, April 13, 1965.

“As for our sound,” continued Kantner, “It’s not folk music. I don’t know what it is. It’s just we all took up and started in folk music and then branched out. Jefferson Airplane had the fortune or misfortune of discovering Fender Twin Reverb amps and LSD in the same week while in college. That’s a great step forward.

“In San Francisco we had no restrictions,” Paul explained to me in 2014. “We never thought about being in an independent record label for cred. It came to us. All we had to do was roll with it. I liken it to white water rafting. There was so much going on you didn’t worry about what was around the next curve. Or what are you going to do on the third curve. ’Cause you are right in the river. San Francisco is 49 square miles surrounded by reality.”

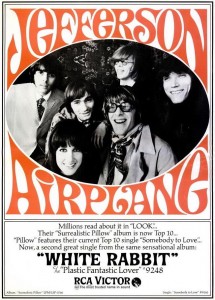

Jefferson Airplane was signed by RCA Victor and recording began in late ’65 with producer Tommy Oliver.

The original lineup completed the recording of their debut LP, Jefferson Airplane Takes Off, issued in September, 1966.

“Jefferson Airplane had played at the September 1966 Monterey Jazz Festival. We were invited because we were the new hip band. The critic Leonard Feather wrote we sounded ‘like all the delicacy and finesse of a mule knocking down a picket fence.’”

The enticing LP housed the riveting rock and folk early FM radio staple, “It’s No Secret,” penned by Balin.

“I originally wrote it with Otis Redding in mind,” Balin recalled in a 2014 interview we did. “It was for him. I used to hang out with Otis and follow him around like a little puppy dog and watch his shows. Hang out with the band and him. I just wanted to write him a song that had his kind of groove thing I thought. But Otis never did it. He did write his own songs.”

“We did ‘High Flyin’ Bird,” added Kantner. ‘Signe drove that song well. The song carries itself. The idea is that songwriters should write good songs.”

As Jefferson Airplane’s debut disc was being shipped, Anderson, pregnant, left the outfit, and was replaced by singer and songwriter Grace Slick from the local group the Great Society.

Drummer Skippy Spence also split the scene, and joined a new group, Moby Grape. Spencer Dryden, a veteran of the L.A. music scene, and a drummer at Hollywood strip joints, who earlier attended the Westlake School of Music, was recommended by Earl Palmer for the slot.

“The whole nature of our whole band is six very different people. Musically and personality wise,” Kanter suggested. “None of us played blues. Jack (Cassidy) wasn’t so much a blues player as an orchestral something or other. Jorma was blues. Gary Davis. Signer was Signe. Grace was Grace. Marty was Marty from show biz.

“We were very different people. Skip Spence was an amateur guitar player and we needed a drummer. And he just wanted to be in a band. ‘I’ll be the drummer.’ And he had a good energy to him, although he wasn’t disciplined. And it worked out pretty good. So who is to complain? Spencer Dryden who joined for Surrealistic Pillow came from a jazz background and Los Angeles.”

In 1967 the new lineup delivered Surrealistic Pillow in February. It contained two songs that Slick brought with her from the Great Society, “Somebody To Love” (written by her brother-in-law Darby Slick) and “White Rabbit” (written by Grace), along with “Today” (Balin/Kantner), and Jorma’s cosmic instrumental “Embryonic Journey.” “Somebody To Love” and “White Rabbit” became back-to-back Top 10 hits dominating the airwaves before, during and after 1967’s notorious Summer Of Love.

As anthems for a generation, they propelled the album to #3 RIAA gold sales, and put psychedelic rock on radio’s front burner.

“I’m still not tired of playing ‘Somebody To Love,” Kantner underscored in a 2012 chat. “I’m still fascinated largely by the metaphysic, if you will, of the music itself. And the why it effects people the way it does. How such a relatively simple combination of elements, be it a large orchestra, or a simple 3 piece rock ‘n’ roll band, is able to communicate emotion to people. That connection still remains a mystery to me. And I plummet every night when we play and live it to hell and don’t need to find out the why of it. If I do it might ruin the whole thing, you know. But being able to manipulate it as we do and do this and the other things, is always fascinating to me.

“Mistakes become part of the arrangement. As jazz people used to say. Or as Jorma used to say, ‘when you make a mistake on a guitar repeat it.’ Everybody thinks it’s part of the arrangement.

“Marty and I worked ‘Today’ up together. We wrote several things in those days. He’d bring a piece and I’d bring a piece and we’d put them together and weave them. And they fell together in the studio. Jerry Garcia played on the track in the studio. When we took it out on stage and did it with our group, it became piano.

“On our first U.S. tour we were in cities where all the kids came in prom gowns and tuxedos. Then we came back to Iowa a year later and they were having nude mud love-ins and everybody had their faces painted.”

Their success earned Jefferson Airplane a level of artistic freedom that resulted in their next album, the song-cycle concept suite After Bathing at Baxter’s. Issued in November, it included Kantner’s opening composition “The Ballad Of You & Me & Pooneil” (which just skirted the Top 40).

Then 1968 arrived. The assassinations of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (in April) and Senator Robert F. Kennedy (in June), escalation of the war in Southeast Asia, and a bitter presidential race are backdrops for the recording of “Crown of Creation,” an explosive new LP issued in August. Dark yet hopeful, it included the opening “Lather” (Slick), the title tune “Crown Of Creation” (Kantner), and Dryden’s only solo writing credit in the Jefferson Airplane canon, “Chushingura.”

Cave Hollywood’s David Kessel in the green room with Paul Kantner at a Jefferson Starship gig April, 2011

The year 1969 began with the February release of Bless Its Pointed Little Head, a live album compiled from performances at Bill Graham’s Fillmore West and Fillmore East in late-’68.

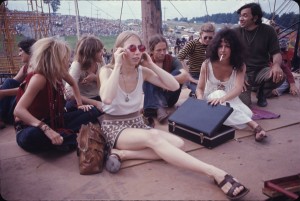

In between their milestone performances at the Woodstock Music & Arts Fair (in August) and Altamont Speedway with the Rolling Stones (in December), Volunteers was issued in November.

Some of Jefferson Airplane’s most overtly political and confrontational material shared the program with wistful songs of romance and faith. Included were “We Can Be Together” (Kantner, with its provocative rallying cry, “Up against the wall, motherfuckers!”), “Good Shepherd” (a spiritual reworked by Jorma, with Jerry Garcia sitting in on pedal steel guitar), and the title tune “Volunteers” (Balin/Kantner, Balin’s only contribution to the album).

Paul co-wrote the post-apocalyptic escape tune, “Wooden Ships” with Crosby and Stephen Stills, done by Crosby, Stills and Nash and Jefferson Airplane.

In 1970, there was the enjoyable Kantner and Grace Slick 1970 fronted concept album, the science-fiction-driven Blows Against The Empire.

In 2010 I interviewed Kantner about Jefferson Airplane.

Q: Talk to me about the legacy of Jefferson Airplane.

A: We put it out in the universe and see where it lands. Sometimes you keep a little control over where it lands more often than not. I like things going out connecting with other things. I’m very much on collaboration as a writer and a player. I like collaborating. I like the friction that happens and the fire that occurs as a result of that friction that comes out in music in other way that comes from collaborating in other levels.

“There was a message there but we didn’t blare it out. We just tried to show by example what you could get away with basically. We tried to propose a real alternate quantum. And did. Enjoying our day. And that’s all we tried to put across. You can enjoy your day. Hedonistic or Dionysian on some levels. That existed.

“And San Francisco was very good, I think, particularly the musicians at transmitting the goodness of the day, rather than complaining about the badness of the day. Creating another universe if you will, or at least a semblance of another alternate quantum that worked for us. And God knows why we got away with it 90 per cent of the time if not more. We should have been in jail, dead, run over by trucks and a number of things over the years.

Q: What do you remember about the Monterey International Pop Festival?

A: I saw cocaine for the first time at Monterey Pop. Something changed. And then I spent a delightful year on it. (laughs). And then I spent a not as delightful but still delightful second year on it. It was irrelevant and it’s not a good long term drug. But it’s a negative drug in the overall. But it’s an exhilarating drug at first. In our profession it’s also imminently available all the time.

“We played on acid so what do I know? I had a great time on acid. We later named a music publishing company Ice Bag which had nothing to do with cocaine. It was good marijuana. The best of the year if not the decade.

“I wasn’t aware of the record business, or music scouts at the Monterey Pop Festival, either. We just came to have a good weekend and play, basically. No chains. And that was what was so glorious about San Francisco in those days.

In 1978 I interviewed Paul at Wally Heider’s studio in San Francisco around their “With Your Love” recording session, and later, inside the landmark Jefferson Airplane house at 2400 Fulton Street.

Q: You have had a commercial re-birth as Jefferson Starship, somewhat owing to the songwriting efforts of Marty Balin on “Caroline” and “Miracles.”

A: Our rebirth, as you put it, can be partially linked to the whole squashing-down effect from 1968-74 politically and socially. Artists and people in general watching out for the rain cloud. Good things come out of tensions. We’ve had a lot of tensions this year. I like bouncing ideas off people who like to work together.

“There’s a little magic in a band when people decide to put their heads and minds to one thing and it works. It becomes more than the people involved.

“With the Airplane we thought we could do it all. It was a reaction against the corporate structure trying to impose certain limits on you. We revolted against that, which was the other extreme, which is doing it totally ourselves. And it was like putting a five-year-old in an automobile reeling down the street. It may make it down the street but the car may get a few dents along the way. The live experience is necessary for a group. The studio is like making a long photograph.

Q: Talk to me about the Avalon and Fillmore venues and the 1967 Summer of Love, a subject that has always fascinated me.

A: The Fillmore and the Avalon. I went to the Human Be In. The summer before the summer of Love I always mention. Everything was possible. And plausible, even. And we got away with it all. More or less. Mostly. You went to the park, the Fillmore, Monterey, to get absorbed in the whole whatever it was going on.

“FM radio was one of the many things that showed up and was going on in those days. So many things were going on you didn’t take that kind of notice of them. You just assumed that was going on. All right! And go with it. We didn’t analyze it. We didn’t think to wonder about it. It was just another thing that was going on along with the music, the clothes, the book stores, the poets, the artists, there was a plethora of things and you did not have time basically to take it all in. It existed. It’s part of a whole.

I plan to spotlight the now-missed voice of Paul Kantner in a book I will be writing and assembling, 1967-A Complete Rock Music History of the Summer of Love.

(Harvey Kubernik has been a music journalist for over 44 years and is the author of 8 books. During 2014, Harvey’s Kubernik’s Turn Up the Radio! Rock, Pop, and Roll in Los Angeles 1956–1972 was published by Santa Monica Press.

In September 2014, Palazzo Editions packaged Leonard Cohen: Everybody Knows, a coffee—table—size volume written by Kubernik, currently published in six foreign languages. BackBeat/Hal Leonard Books in the United States.

Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik wrote the text for photographer Guy Webster’s first book for Insight Editions published in November 2014. Big Shots: Rock Legends & Hollywood Icons: Through the Lens of Guy Webster. Introduction by Brian Wilson).

In November of 2015, BackBeat/Hal Leonard in the U.S., Omnibus Press in the U.K. and four other foreign language editions published Harvey’s book on Neil Young, Heart of Gold.