With the passing of David Bowie, Cave Hollywood thought it was appropriate to display a 2003 interview Harvey Kubernik conducted with Oscar-winning filmmaker and documentarian, D.A. Pennebaker, who directed 1973’s Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars.

appropriate to display a 2003 interview Harvey Kubernik conducted with Oscar-winning filmmaker and documentarian, D.A. Pennebaker, who directed 1973’s Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars.

The documentary has been out on DVD for many years.

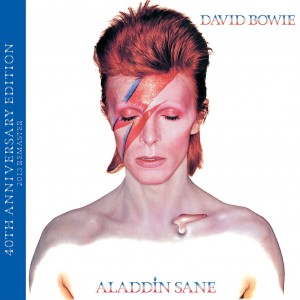

Pennebaker’s riveting celluloid portraits captures Bowie’s last performance as Ziggy while introducing musical aspects of Bowie’s ongoing 1973 journey that resulted in his “Aladdin Sane” album.

D.A. (Donn Alan) Pennebaker was born July 15, 1925 in Evanston, Ill.

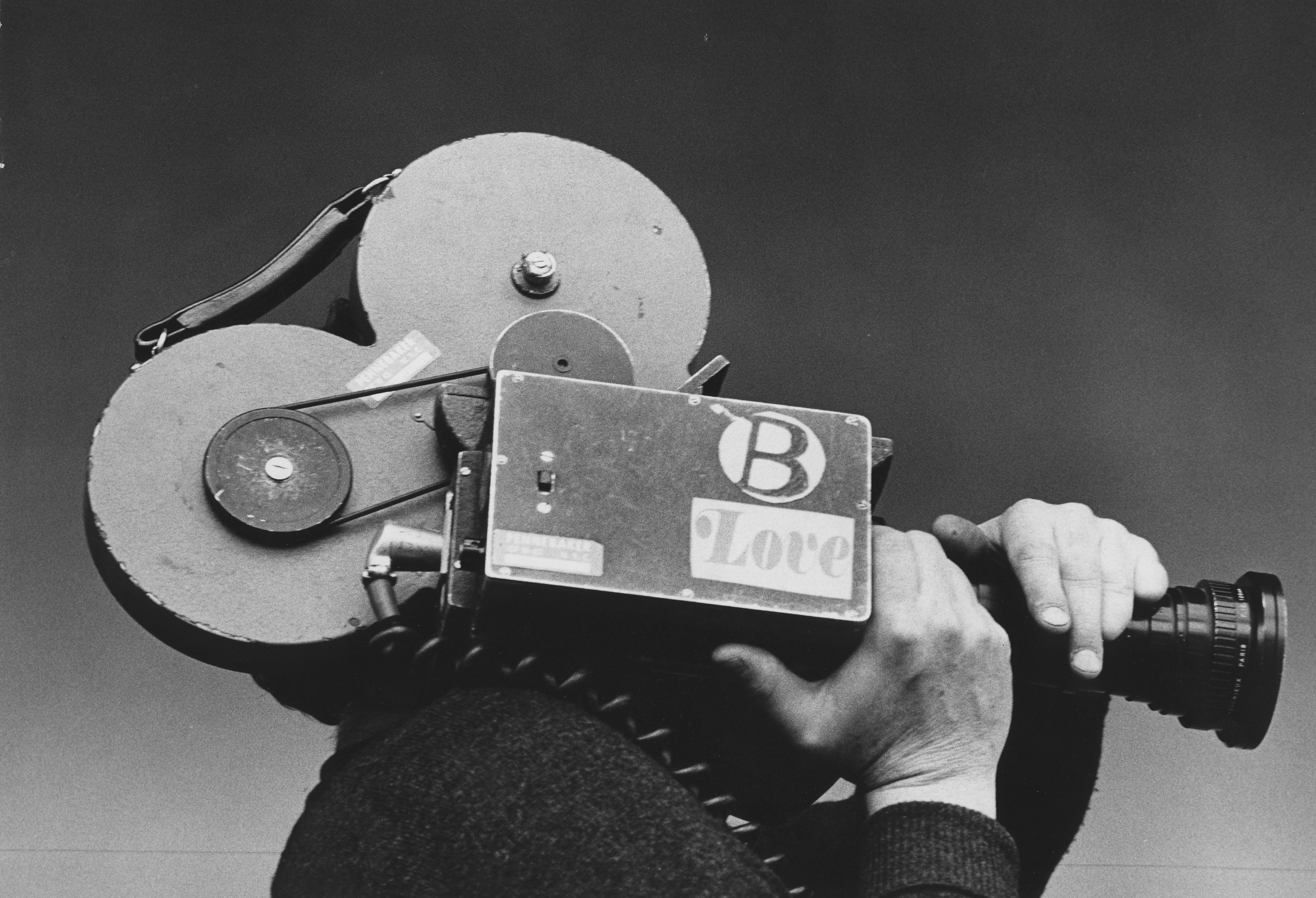

His body of work has always had a strong relationship to music, especially rock ‘n’ roll. Pennebaker made his filmmaking debut with the 1953 short “Daybreak Express,” an abstract five minute piece about the Third Avenue L Train set to the celebrated Duke Ellington song. In 1959, Pennebaker, along with Richard Leacock and Albert Maysles, joined Drew Associates, a group of filmmakers organized by Robert Drew and Time, Inc. which was dedicated to expanding the use of film in journalism. Pennebaker and his partners forged the use of the first fully portable 16mm synchronized camera and sound system. The “direct cinema,” or “cinema verite,” an unobtrusive style of filmmaking brought viewers right in to the action, when they previously felt isolated from traditional narration documentaries. Together they produced such landmark films as 1960’s “Primary,” about Hubert Humphrey and John F. Kennedy in Wisconsin, and “Crisis,” a confrontation between Att. General Robert Kennedy & Gov. George Wallace over desegregation of the University Of Alabama. The group also did “Jane,” which chronicled actress Jane Fonda’s Broadway debut.

In 1964 Leacock and Pennebaker formed their own company and in 1965, Albert Grossman, Dylan’s manager approached them about filming Dylan’s ’65 tour. The film was released in 1967.

Pennebaker’s next major film event was “Monterey Pop,” capturing the wonderful West Coast 1967 festival that showcased Jimi Hendrix, Otis Redding, Janis Joplin, The Who, and Jefferson Airplane. He is currently preparing a DVD of “Monterey Pop” with Lou Adler.

An additional film he made in 1970 was a documentary he made around the recording of the original cast album to Stephen Sondheim’s “Company,” now out in retail outlets.

In 1972 his “Keep On Rockin’” was released with Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry and Jerry Lee Lewis, among others. In 1973, Pennebaker filmed David Bowie’s final concert appearance as “Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars.” In the last couple of decades his links to music and film collaborations have continued.

HK: In 1973 you did the film David Bowie’s “Ziggy Stardust and The Spiders from Mars.” A cinematic dude. I would also imagine you connected with him, who knows, maybe afterwards, partially ‘cause he nicked the line ‘spiders from Mars’ from Kerouac’s “On The Road,” and has acknowledged beat writer William S. Burroughs’ cut up method on his own songwriting.

DAP: There’s a kind of aspect to this kind of film making, “Don’t Look Back,” “Ziggy,” “Down From The Mountain,” that you don’t much learn it but it’s a rigor that you have to sort of go through. When you first start a film, like when I first met Bowie, the first shot I ever took of him was still the best shot I ever took of him. It’s on my wall somewhere. It’s like that moment you want to fix a face so that the audience will remember that face forever. Because it’s really hard in a documentary getting people on stage. They all look alike. No matter how different they are. One is blonde, one has brown hair.

Q. But with David Bowie and his Ziggy character you were walking in to a situation where things were pretty colorful and theatrical already underscoring the music being created.

A. Yes, but the dressing room was where you see him just sitting there, so that in the beginning you use a long lens, that’s why I use a zoom, and you can stand far away and the sound person can be close and you can really get on stage physically So people know that he looks different from somebody else. If you take these faces right you do portraits. But then as the movie goes forward somewhere down the line there comes a point where you don’t need to do that anymore so you go to wide angle. And usually with wide angle you usually don’t have a finder ‘cause you got to line up and pull the camera up and you start getting what is happening rather than picture to music. From then on everybody is going to recognize who’s who and you don’t have to worry about it, and that’s the way the films go, most of them.

Q. You walked in to a cosmic moment in history. Bowie came to the party with the whole package, and you were getting his last “Ziggy” show. Were you a fan before you did the project?

A. No. I didn’t know who he was! I thought it was Bolan. I thought I was going to see Bolan and I loved glitter rock and I didn’t know much about it.

At the time before ‘Ziggy,’ I was out on the Mississippi on a raft and ABC got hold of me and said ‘we want you to go do a film of David Bowie.’ I thought they said Bolan, Marc Bolan. I think, ‘this is great, glitter rock’ But I said ‘I can’t, I’m on this raft.’ They called back a day later and said ‘you gotta go and we’ll fly you out…’ We couldn’t get out of New York because there was some sort of strike so we actually had to take a tour plane that we snuck on to with our equipment to Italy, to Rome. There had been a big thing of terrorists at the airport there so they arrested us. Guys got out with machine guns. We finally got through that and got to London and we got there two days before the concert.

So we saw one concert that night. I saw him once and I shot some stuff ‘cause I wanted to see if we needed to lift the lighting or anything. And the lighting I could see was really crucial to this. We couldn’t fake it. I shot some stuff and we took it down that night to a lab and they processed it and we looked at it and I made a couple of changes, like the blues were too strong and I went over it with the lighting person. And the next night we did the whole concert and there were only three of us. We had a skeletal crew and a Brit we hired with a camera way back in the rafters to get a broad shot in case we ever needed it, but we never actually used it.

So we saw one concert that night. I saw him once and I shot some stuff ‘cause I wanted to see if we needed to lift the lighting or anything. And the lighting I could see was really crucial to this. We couldn’t fake it. I shot some stuff and we took it down that night to a lab and they processed it and we looked at it and I made a couple of changes, like the blues were too strong and I went over it with the lighting person. And the next night we did the whole concert and there were only three of us. We had a skeletal crew and a Brit we hired with a camera way back in the rafters to get a broad shot in case we ever needed it, but we never actually used it.

Q. And the glitter critters in front of the stage really knocked me out in the film. What about Bowie in the dressing room? There was a little Ringo action.

A. There was a lot of kinetic energy around Bowie. He was like an orchestra leader. I was a fan of the ‘Ziggy’ album and we used to play it all the time when I was mixing that film. I had it set up actually a real Dolby and we showed it in this little room where the sound was fantastic and that was the sexiest film you ever saw in your life.

Q. He had the ability to project to both men and women.

A. Absolutely. I mean, I could practically feel myself getting a hard on watching it. (laughs). I don’t know. He represented sexuality without it even being a man or a woman. It was an element of it.

Q. Did you see any artistic similarities to Dylan?

A. Maybe. Dylan used to dress up and do funny things. He’s kind of like David and I told Dylan once this and he was sort of anxious and said, ‘yeah…’ I remember him on the phone. They were kind of alike, but they didn’t seem alike at all, so it surprised me.

Q. Both Dylan and Bowie had when you worked with them had an extensive grasp of song and music history.

A. When I first met Dylan at the Cedar Tavern (in Greenwich Village, New York) we talked and there was a woman sitting in the corner of the bar and Dylan asked me if I thought it was Lotte Lenya. I was interested that he even knew who she was.

Q. And during his “Ziggy” period, Bowie did a Jacques Brel song, “My Death” in the concert.

A. Oh yeah!

Q. David may have gotten the Brel songbook from Scott Walker before him, who used to do Brel tunes. That was my favorite piece in the “Ziggy” movie.

A. Why?

Q. ‘Cause it’s so haunting and slow, and him with the guitar.

A. And he draws you out.