By c Harvey Kubernik

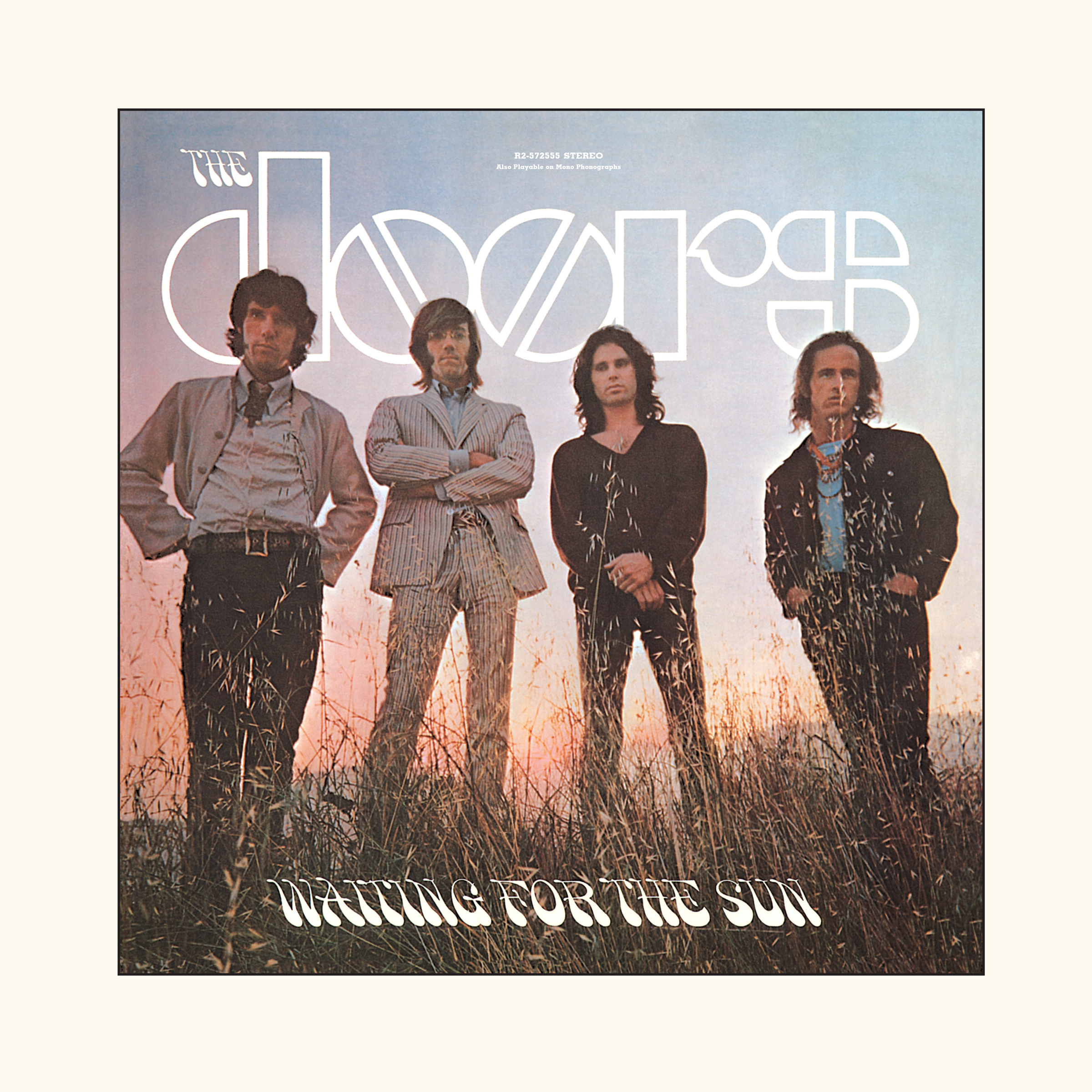

A 50th anniversary deluxe edition of Waiting For The Sun from The Doors [Ray Manzarek,

Jim Morrison, John Densmore, Robby Krieger] was just released in September from Rhino Entertainment.

Initially shipped to retail outlets on July 3, 1968 on the landmark Elektra Records label, founded by the visionary music man Jac Holzman, the album was engineered by Bruce Botnick and produced by Paul Rothchild. Holzman served as production supervisor.

It was the band’s third platinum LP in less than two years and their first to top the album chart. A single culled from the collection “Hello, I Love You” was a number one smash.

This 2018 2-CD, 1-LP collection offers fans a new version of the original stereo mix of the album on CD as well as on 180-gram vinyl, remastered by Botnick, The Doors’ longtime engineer-mixer, from the original master tapes.

In addition, the package houses 14 completely unreleased tracks: nine “rough mixes” from the original recording sessions which were only recently discovered, and five live performances from a September 17, 1968 performance by the band at Falkoner Centeret in Copenhagen Denmark.

The booklet contained in this Waiting For The Sun 2018 reissue, with a slew of rare and never seen Paul Ferrara photographs is stellar.

The Doors started production with the Rothchild and Botnick team at Sunset Sound for Waiting For The Sun at the Sunset Blvd. facility in Hollywood where they had collectively done their first two epic albums, The Doors and Strange Days.

“I was more impressed by Ray Manzarek at the beginning than I was by Jim,” recalled Holzman in a 2017 I conducted with him. “Jim had the vocal chops but that personna crept out once he knew he had a safe home or a safe perch to work from. Remember: The Doors were a band that had been signed to Columbia and they couldn’t even get to make a single. And the reason I offered them a three-album guarantee was that I never wanted them to feel that they would get booted out the door if the first LP didn’t sell. So that was the genesis of that.

“My relationship with producer Paul Rothchild started in 1963,” Jac remembered. “He was unhappy at Prestige Records. I offered him a job to work for me after he started to complain about his boss, mainly because Paul and I could see things.

“I went into the [Sunset Sound] studio and there was this kid there and I thought he was the guy who handed the engineer the tapes. I got there really early. It was Bruce Botnick. And we hit it off real well. And at the end of the sessions he took me out to dinner and asked ‘if there ever was a chance for me to work for Elektra I’d like to do it because I like the way you guys go about things.’

“I produced Love’s ‘7 and 7 Is.’ He engineered it. And because I was so comfortable in that studio and I trusted Paul implicitly and I also trusted Bruce and I felt Bruce and Paul would make a combination where two would add up to three. That’s exactly what happened.

“Bruce has solid producer chops. Forever Changes would not have happened without him.”

“Paul Rothchild was the guy who had produced The Paul Butterfield Blues Band and also Love, along with engineer Bruce Botnick,” Ray Manzarek told me in a 2006 interview. “The two of them did those albums together. So it was a great combination of six guys. We made the music. They made the sound. And they did an absolutely brilliant job. And it was a real joy and a great learning experience.

“Rothchild and Botnick were two alchemists with sound. We were the alchemical music makers but they were alchemists with sound-adding a bit of this-a bit of that. ‘Some reverb. Some high end. Let’s hit it at 20k or 10k. Let’s dial in a bit of bass in there.’ They were making this evil witches brew concoction as we went along. And the sound just got better and better. Sunset Sound was a place where we could really experiment.”

In a 2009 interview, Bruce Botnick described Sunset Sound to me.

“Tutti Camarata, a trumpet player originally and an arranger, and did big band stuff in the 1940s and ‘50s had a friendship with Disney and decided to build a recording studio to handle the Disney records and all the movies. The room was very unique. Tutti Camarata did something that nobody had done in this country. He built an isolation booth for the vocals. It was great.

“It had an amazing echo chamber that Alan Emig designed. You have to remember in those days all the studios built their own consoles. It was built by Emig, who had come from Columbia Records. He was a well-known mixer there and designed a custom built 14 in-put console for Sunset Sound.

“The consoles were all tube. At one point Alan had worked with Bill Putnam, who had helped design the two pre amps in all the Universal Audio consoles. So when he came to Sunset Sound and he took it a step further and built this custom board with some of that circuitry and the two pre amps. So it really sounded great.

“United Recording Studios, Western Recorders, Gold Star, Sunset Sound, RCA were terrific rooms. There was a commonality between them. They all had the same Altec Lansing 604E loud speakers. So you could walk from studio to studio and know what the hell you were hearing. Some rooms had more bottom than others. But still the general, overall sound was the same. So you could take your tape and go to another room.

“As for tape, it was Scotch 111. The Scotch tape, first off, you could kill it, and today it still plays. The oxide is still on the backing. A lot of the later low noise tapes that happened, especially with Ampex and some Scotch 207, the oxide turned to mush due to the backing and the glue. But generally the favored tape was Scotch.”

After “Unknown Soldier” and “Spanish Caravan” were recorded at Sunset Sound, the band opted for a change of scenery. Rothchild and Botnick booked TTG Studios on North McCadden Place right near the intersection of Sunset Blvd. and Highland Ave.

In the fifties and early sixties TTG had been Radio Reorders and later Conway Recorders before TTG obtained the property license. The venue was owned by sound engineer Ami Hadini and Tom Hidley, who had installed a 16-track machine, one of the first in town. Bill Parr, formerly of Conway designed the custom TTG board utilized for film scoring upstairs.

The Mothers of Invention cut Freak Out! and Absolutely Free at TTG with producer Tom Wilson. The Velvet Underground and Nico along with Winds of Change, by Eric Burdon and the New Animals also recorded with Wilson during 1967.

TTG was also equipped with Ampex 351-2 and 440 tape recorders to augment a 3M 8-track recorder that Botnick and Rothchild employed on Strange Days. In addition, TTG had EMT 140 Echo Plates along with Sony and Telefunken microphones. Interestingly, Morrison’s vocals were delivered at TTG on an AKG C12 microphone, and not the normal Telefunken U47 at Sunset Sound implemented on The Doors and Strange Days.

In his illuminating technical-centric package notes to 2018’s Waiting For The Sun booklet, Why In Hell Should I Buy Another Version Of Waiting For The Sun When I Own So Many Other Versions Already?I Think I’m Being Ripped Off!!!!, Botnick also suggested another reason why this album sounds so fuckin’ good.

“Our album was kind of a first, as we used the new Dolby A301 noise-reduction processors; Elektra Records was the first U.S. label to exclusively use them on all of their albums. We had eight stereo units, four each for the respective encoding and decoding processes. Couple the quietness of the Dolby’s and the deadness of TTG’s carpeted studio, and it was almost inert.”

At least once a week during 1968 when I wasn’t frequenting The Hollywood Ranch Market on Vine St., I’d go to Stan’s Drive-In, next to TTG for their milkshakes, served by very attractive carhops. In fall of ’68 Jimi Hendrix did some sessions at TTG.

In 2008 I interviewed John Densmore about Waiting For The Sun. I asked about “Love Street” and his memories of Sunset Sound.

“I love the melody on ‘Love Street.’ I thought it should have been a single and I know it’s kind of light to the dark Doors, but I just love the melody. Melody is paramount for me. I’m a drummer.

“Sunset Sound had a real echo chamber like the famous echo chamber at Capitol and it had a pocket that was fat. Just a warm fat echo chamber. You can’t buy that kind of shit.

“First of all when I went into Sunset Sound in the very beginning I had no clue what a good drum sound was. And I couldn’t believe you had to change the sound and kind of muffle it. Which Rothchild taught me. I loved Paul Rothchild but he got so perfectionist.

“He was tough but taught us so much. And mid-period, Waiting For The Sun and The Soft Parade, he had me doing a drum sound to tap on each drum and I’d have to do it for a fuckin’ hour. And I was exhausted. We did a 100 takes for ‘The Unknown Soldier.’

“Cream’s ‘Sunshine of Your Love’ was out and we’re in the studio, trying to play ‘Hello, I Love You.’ Robby says, ‘Why don’t you try and do that Cream beat where Ginger Baker sort of turns it around.’ And I did. Two bars of Ginger Baker are in ‘Hello, I Love You.’ (laughs).”

During 2011 I discussed Waiting For The Sun with Ray Manzarek.

Q: This album had some songs that already existed in raw form going back to 1965 but a lot of new material was specifically written for this disc.

A: You know it’s time to do a record when you have 10 or 12 songs together. When it hits a dozen time to enter the recording studio. I mean, we worked on those songs. I mean, when we would get together in the rehearsal studio they were polished. They were changed. They were adapted. Somebody, invariably Robby or Jim who would come up with the original idea. But boy, the four of us would get together, change and modify and polish the songs.

Q: “Hello, I Love You” from Waiting For The Sun had been around since 1965.

A: Yes. It was a song Jim wrote on the beach when we used to live down in Venice. Dorothy would go off to work and Jim and I would go off to the beach around the rings on the sand at Muscle Beach and work out around the bars, rings and swings and get ourselves into physical shape. He was gorgeous. Man, he was perfect. He was a guy who had opened the doors of perception and made a blend of the American Indian and the American Cowboy. He was the white Anglo Saxon Protestant. The WASP who had taken on the mantle of the American Indian. He now was no longer a fighter of Indians. He was a lover of American Indians.

“I knew Jim was a great poet. There’s no doubt about that. See that’s why we put the band together in the first place. It was going to be poetry together with rock ‘n’ roll. Not like poetry and jazz. Or like it, it was poetry and jazz from the ‘50s, except we were doing poetry and rock ‘n’ roll. So Jim was a magnificent poet. I loved his poetry. The fact that he was doing ecological poetry.

Q: Like poet Gary Snyder and his writings and prose on nature.

A: Sure, absolutely man. But don’t forget that’s late 1967, and the potheads were aware. That’s what was so great about marijuana opening the doors of perception along of course with LSD. Marijuana makes you aware that you are on a planet.

“It’s God’s good green earth and you’ve got to take care of God’s good clean earth. The pot heads were the first mass ecological movement. And I hope they continue on and continue it into future because it’s our obligation to save the planet.

Q: You served in the military in 1963 before the Doors started. In the U.S. Army stationed at a Southeast military base in Korat, Thailand. The Doors’ “Unknown Soldier” was partially informed by your hitch. And Jim’s father Steven Morrison was a rear admiral and commander of naval forces in the Gulf of Tonkin in August 1964 which is considered an escalation moment of the Vietnam war.

A: Everyone had to do military service. This was a time just before Vietnam. I was lucky. Everybody had a military obligation. You had to do your time in the service. So I did my time. Besides Thailand, I went to New York City and then I went to Okinawa, fell in with a bunch of jazz musicians, smoked a little grass there. I thought it was fabulous.

“I didn’t grow up with reefer madness and paranoia. I was a musician. I initially knew it from guys who were jazz musicians and smoked it. Then I went to Thailand and where I had my real first Thai stick experience. Courtesy of Uncle Sam.

Q: On Waiting For The Sun, The Doors question government on “The Unknown Soldier” and “Five To One.”

A: That was a time when we started questioning the government. Everyone was questioning the government. That was all based on the war in Vietnam. And why are we in Vietnam? Why are we fighting these people?

“By the third album, Waiting For The Sun, Paul Rothchild was becoming a real Laurel Canyon connoisseur of veteran potent stuff that was being crossbred by the Northern California growers. All those guys up in Humbolt County.

“For recording sessions, Rothchild had two types of marijuana: Work dope and also playback dope, which was a little stronger for listening later. One of the benefits of being a known rock ‘n’ roll band. It was a very Laurel Canyon scene.

Q: “Celebration of The Lizard” from Waiting For The Sun. Morrison’s lyrics are prophetic. There are warnings about the environment which are really obvious in “Not To Touch the Earth.” In December 1968 I saw the Doors perform it at The Forum.

A: Sure. Yes. Ecology was very, very big. We were all trying to save the planet. The sun was the energy. The supreme energy. The establishment, as we called it, the squares, as they were called in the fifties, the establishment as they were called in the sixties, were trying to stop drug use. The smoking of marijuana.

“They were trying to stop any kind of organic fertilizer. The word organic to them meant hippie, radical pot heads and people who wanted to leave behind the organized religions and start some new tribal religion based on American Indian folklore. That’s indeed what we were. We called ourselves the new tribe.

“The vegetation of Laurel Canyon was very conducive to songwriting. The Doors were always part of nature. It was always intense and closed and locked in with the four Doors entering that unified space that they occupied of creativity. It didn’t matter where we were. We could be in a Hollywood recording studio or Laurel Canyon, or at the beach. It always had to do with the music and the submersion in the music.

Q: The LP was titled Waiting For The Sun but the actual song of the same title ends up on an album, Morrison Hotel.

A: How ‘bout that, man. Well, you know what happened? We all loved that title, Waiting For The Sun. That’s what we’re all doing. That’s what everybody is doing. Everyone is waiting for that sun of enlightenment. That blasting searing sun. The purity of the sunlight to be purified. To leave our closed circle bodies and expand into the light. And we have a song, time to go into the recording studio, and the one song that hasn’t jelled is ‘Waiting For The Sun.’ It was not right. Well let’s call the album Waiting For The Sun anyways. That’s how it happened.

“Songs were like that. Not how long they would take. You had to put them in the oven and bake them in the collective oven mind of The Doors. And some of them came out virtually. That song is right. That song is the way it should be. Others took longer. ‘Waiting For The Sun’ was a song that had a long gestation. But the baby was certainly worth the wait.

Q: I think that you and Jim graduating from the UCLA Film School really informed your songs in the cinematic sense. And consequently the music of the Doors became timeless.

A: We never tried to be of the moment. We always tried to make pictures in your mind. Your mind ear. You hear pictures with the music itself. We were working in the future space. The Doors on their third album were in the future. And many things have come to pass that Jim Morrison wrote about.

“After I graduated from UCLA in the spring of 1979,” disclosed Lonn Friend, author of Life on Planet Rock and Sweet Demotion, “I landed my first job at the Registrar’s Office in Murphy Hall where I assisted students needing to access their transcripts (grades records) for various reasons.

“Decades before anything was online or digitized, the basement of our brick house offices contained rows and rows of old steel file cabinets, hard copy archives of every Bruin that ever did scholastic time on the Westwood campus; picture a limited vista of Raiders of the Lost Arc’s final scene.

“During my lunch hour, I would occasionally snoop around the massive, dimly lit room, thumbing documents in search of famous folks that I knew had shared my alma mater, iconic names like Francis Ford Coppola, Carol Burnett, Carlos Castaneda…and Jim Morrison.

“Having owned every Doors record since the ‘break on through’ debut blew my pre-pubescent mind, I was especially moved examining the less than Phi Beta results of the Lizard King. Got me thinking, hey, maybe college isn’t all its cracked up to be. Look what Jim did! His was the only transcript that I secretly photocopied, gentle guerrilla move for a poetic hero that lived his life on Love Street.”

(Harvey Kubernik is the author of 15 books, including titles on Leonard Cohen and Neil Young. His 2017 volume, the acclaimed 1967 A Complete Rock History of the Summer of Love was published by Sterling/Barnes and Noble. Inside Cave Hollywood: The Harvey Kubernik Music InnerViews and InterViews Collection, Vol. 1 was published in December 2017, by Cave Hollywood. Kubernik’s The Doors Summer’s Gone was published by Other Cottage Industries in March 2018.

In November 2018, Sterling/Barnes and Noble published Harvey’s book, The Story of The Band From Pig Pink to The Last Waltz, written with brother Kenneth Kubernik.

In November of 2006, Harvey Kubernik was a featured speaker discussing audiotape preservation and archiving at special hearings called by The Library of Congress and held in Hollywood, California).