To Be Released November 13TH From Ume/Polydor; Bobby Whitlock Interview;

Chris Darrow on guitarist Duane Allman

By Harvey Kubernik c 2020

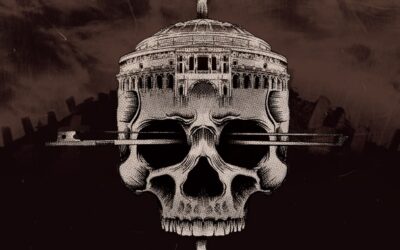

This November sees the release of 50th Anniversary edition of Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs, available as a 4LP vinyl box set via UMe/Polydor.

In celebration of the 50th anniversary of the 1970 double album, the original has been given the ‘Half-Speed Mastered’ treatment by Miles Showell at Abbey Road Studios and is completed with a certificate of authentication.

Layla is often regarded as Eric Clapton’s greatest musical achievement. The album is notably known for its title track, an evergreen rock classic, which had top ten single chart success in the U.K. and features the dual wailing guitars of Clapton and Duane Allman. Alongside this are a further 2LPs of bonus material some of which has not previously been released on vinyl.

All the bonus material across all of LP3 and LP4 is mastered normally (so is not half-speed mastered). The LP set also includes a 12×12 book of sleeve notes taken from the 40th-Anniversary Edition.

Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs (4LP)

LP1/ LP2

Side A

- I Looked Away

- Bell Bottom Blues

- Keep On Growing

- Nobody Knows You When You’re Down And Out

Side B

- I Am Yours

- Anyday

- Key To The Highway

Side A

- Tell The Truth

- Why Does Love Got To Be So Sad?

- Have You Ever Loved A Woman

Side B

- Little Wing

- It’s Too Late

- Layla

- Thorn Tree In The Garden

LP3 / LP4 – Bonus Material (*denotes previously unreleased on vinyl)

Side A

- Mean Old World – Layla Session Out-take

- Roll It Over – Phil Spector Produced Single B-Side

- Tell The Truth – Phil Spector Produced Single A-Side

Side B

- It’s Too Late* – Live On The Johnny Cash TV Show, November 5, 1970

- Got To Get Better In A Little While* – Live On The Johnny Cash TV Show, November 5, 1970

- Matchbox with Johnny Cash & Carl Perkins* – Live On The Johnny Cash TV Show, November 5, 1970

- Blues Power* – Live On The Johnny Cash TV Show, November 5, 1970

Side A

- Snake Lake Blues* – From April/May 1971 Sessions For The Dominos’ Second Album

- Evil* – From April/May 1971 Sessions For The Dominos’ Second Album

- Mean Old Frisco* – From April/May 1971 Sessions For The Dominos’ Second Album

- One More Chance* – From April/May 1971 Sessions For The Dominos’ Second Album

Side B

- High – From April/May 1971 Sessions For The Dominos’ Second Album

- Got To Get Better In A Little While Jam* – From April/May 1971 Sessions For The Dominos’ Second Album

- Got To Get Better In A Little While* – From April/May 1971 Sessions For The Dominos’ Second Album

In 1970, following the break-up of Blind Faith and his departure from Delaney & Bonnie,

Derek & The Dominos initially formed in the spring of that year. The group comprised Eric Clapton on guitar and vocals alongside three other former members of Delaney & Bonnie & Friends: Bobby Whitlock on keyboards, Carl Radle on bass and Jim Gordon on drums. Derek & The Dominos played their first concert at London’s Lyceum Ballroom on June 14, 1970 as part of a U.K. summer tour. During late August to early October they recorded Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs, with the Allman Brothers’ guitarist Duane Allman sitting in, before returning to a tour of the U.K. and the U.S. until the end of the year. Shortly thereafter the group disbanded but their short time together offered up one of the rock canon’s most enduring albums of all time.

It was in 1969, guitarist and vocalist, Clapton, found inspiration and a new set of playing partners in the family-like musical structure of Delaney and Bonnie and Friends – an American, R&B-influenced entourage whose recent UK tour hit the British music scene with seismic ramifications.

Delaney and Bonnie Bramlett in ’69 were an all-star group of “friends” assembled for a weeklong tour of England, a legendary excursion that would be documented with a live album, On Tour With Eric Clapton.

It was Delaney Bramlett during their Blind Faith US tour who had encouraged Clapton to sing. Delaney and Bonnie were the support act on that Blind Faith trek.

Along with the Bramletts, the touring ’69 group included guitarists Eric Clapton and Dave Mason, bassist Carl Radle, drummer Jim Gordon, organist Bobby Whitlock, Jim Price and Bobby Keys on horns, percussionist Tex Johnson, and singer Rita Coolidge. On a Croydon UK show, Mysterioso (aka George Harrison) joined the gang on stage.

Engineer Glyn Johns, who recorded the On Tour With Eric Clapton album, culled from two UK Delaney & Bonnie live concerts at Royal Albert Hall and Colston Hall, remarked about that lineup,

“There is no question that they had an immense effect on popular music, mostly by influencing some of the most successful musicians of the day. The outstanding memory for me is the sound they created. Being an engineer, it had a huge influence on me—this, coupled with the complexity of the rhythm section and the ease with which they performed. Us Brits had never heard anything so fluid.”

The band Derek and the Dominos emerged during 1970 owing to the ‘60s wave of interest in roots music and blues-based rock ‘n’ roll.

The Dominos foursome featured Delaney and Bonnie’s rhythm section – keyboardist/vocalist Bobby Whitlock, bassist Carl Radle and drummer Jim Gordon – plus Clapton on voice and guitars.

Originally Jim Keltner was slated to be the drummer. Jim Gordon intervened when he heard that Clapton was looking for a drummer while Keltner was busy finishing up his recording sessions with jazz guitarist Gábor Szabó.

The formal musical lineup actually first came together in late spring of 1970, developing their sound while performing on George Harrison’s solo album, All Things Must Pass (their studio jams were housed in the three-disc package.)

On June 14, 1970, Derek and the Dominos premiered publicly in London at the Lyceum Theatre. The show announcer mispronounced their names of Eric and the Dynamos to Derek and the Dominos.

“I saw their first performance — at the Lyceum where they were billed as Eric Clapton & Friends,” remembered journalist Fred Shuster.

“I also recall Bobby Whitlock behind a huge Hammond organ, and the perennial Jeff Dexter hosting and not sure what name to use to introduce the band. I think in the end he just said and now, ‘Eric Clapton and the Friends.’ Dave Mason joined them. It was marvelous. The vocals were terrific. But nobody had heard much of the material at that point, although they did cover at least one rock ‘n’ roll standard and something by Delaney & Bonnie.

“I might add that the audience at that time consisted of people, including me, who yearned for the old Cream pyrotechnics. Even though most of us had seen and heard the new milder Eric with Blind Faith at Hyde Park and accompanying Delaney & Bonnie at the Albert Hall, it was still disappointing that there were none of the old jaw-dropping thrills of Eric’s previous incarnation with Ginger and Jack.

“Also, we didn’t know much of the new material and only later, when the double album came out and we allowed it to soak in did we recognize how extraordinary those songs were.”

Despite the tongue-in-cheek, spontaneously chosen name, Derek and the Dominos were a sincere attempt to recreate the friendly, leaderless outfit and easy, groove-driven sound Clapton had earlier crafted in ’69.

By August 1970 Derek and the Dominos began recording their debut album in Florida at Criteria Studios in North Miami, with renowned engineer and their executive producer Tom Dowd in the control room. Engineers Howard and Ron Alpert worked with Dowd during August and September of ’70.

Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs, – the double-album that Derek and the Dominos recorded over the next 6 weeks introduced the creative singing and songwriting axis formed by Clapton and the Memphis-born Bobby Whitlock, who had grown up around the city’s legendary Stax, Hi Records and American Recording Studios.

Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs is a collection of timeless blend of rock, electric blues and Southern gospel and hickory-smoked soul influences that has shaped and inspired generations of roots-oriented musicians.

Clapton’s calling card, “Layla,” and the entire album is filled with laments, emotional odes and horny vocals aimed to his unattainable physical, if not spiritual muse at the time, Patti Boyd, who unsuspectingly, is at the epicenter of his lustful motives and his then narcotic-fueled desires.

Whitlock and Clapton shared a friendship and would write together on their guitars. The confluence of British blues-rock and Southern American R&B informed a number of gospel-inflected tunes that filled the Layla LP.

Various songs implemented the Clapton and Whitlock primary voices harmonizing much in the fashion of a rock-world Stax Records mainstays Sam & Dave.

The results, “Anyday,” “Keep On Growing,” “Tell the Truth,” “I Looked Away,” “Thorn Tree In The Garden,” and “Why Does Love Got To Be So Sad?” have been FM and satellite radio staples for decades along with other selections that were initially serviced to program directors and deejays 50 years ago.

The Layla collaboration also saw the coming together of Clapton and Duane Allman: two guitar specialists hailing from different sides of the Atlantic. They had been together before on tape.

Allman played guitar on the Jerry Wexler-produced Aretha Franklin Lady Soul 1967 album sessions at Atlantic Recording Studios in New York while Clapton supplied an overdub on her “Good To Me As I Am To You” date.

The 1970 Dominos pairing of Clapton and Allman happened when the Allman Brothers Band – then just breaking into mainstream popularity – did a concert in Miami on the second night of the Layla recording sessions.

The musical encounter resulted in a night full of studio jams, followed by the inclusion of Duane Allman’s guitar on the bulk of the album.

Standout string duels on “Key To The Highway,” “Have You Ever Loved a Woman?” and the double slide-guitar workout that defines and blends with the famous piano coda section of “Layla.”

One facet of Clapton’s profound worship of the American blues art form is a prominent thread in the action that is displayed during Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs. The infectious The Clapton and Allman guitar sounds were recorded through Fender Champ amplifiers.

Clapton’s choice of blues-based tunes to populate the disc stretched from Bessie Smith’s 1923 “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out,” to “Key to the Highway,” associated with Big Bill Broonzy, from 1940. The unit’s recorded repertoire also paid homage to Chuck Willis’s 1956 R&B ballad “It’s Too Late, ” Freddie King’s 1960 “Have You Ever Loved A Woman,” and Jimi Hendrix, circa 1967, “Little Wing.”

Two tracks produced by Phil Spector in early summer 1970 amounted to the first release by Derek and the Dominos: “Tell the Truth” and “Roll It Over,” the A- and B-side of a single that was quickly pulled from circulation by the group.

It was shipped during November 9, 1970 to retailers on the Atco label.

The initial issue of the long player album package received little radio airplay for the first year. And, by the time the Layla LP and the “Layla” title track single eventually became a commercial success, Derek and the Dominoes were defunct.

Layla garnered gold-album status within months of its release in late 1970, was entered into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2000.

The Universal Music Enterprises/Polydor product model is a comprehensive salute to this iconic album and the musicians that created it. The product houses the original double-disc album in both digital and vinyl formats, expanded to include newly remastered tracks, and lots of music.

“Got To Get Better In A Little While” – the group’s last recording – positioned in this collection both as a jam version and as the first- ever release of the fully produced studio version, now completed by founding member Bobby Whitlock on keyboards and vocals.

The Layla and Assorted Love Songs configuration now implements all four audio performances from Derek and the Domino’s sole, historic television appearance on The Johnny Cash Show, on November 9, 1970 – including Clapton’s famous jam on “Matchbox Blues” with Cash and rockabilly legend Carl Perkins.

The previously unreleased audio tracks from the Johnny Cash series are “It’s Too Late,” “Got To Get Better In A Little While,” and “Blues Power,” first heard on the debut Eric Clapton 1970 solo album that Delaney Bramett produced.

There is also a Layla session out-take “Mean Old World,” an acoustic duet cut by Clapton and Allman.

I saw Derek and the Dominos on their tour one night on November 21, 1970 at the Civic Auditorium in Pasadena, California. I wanted to see Eric Clapton’s new band. Toe Fat opened.

It was world in Southern California where you could attend a concert and parking was free. The gig wasn’t sold out, either.

I walked up to the ticket window and laid out a $10.00 bill to the girl at the box office for a $6.50 ducat. She subsequently made change from a stack of short bills and coins out of a Muriel Cigars box on the counter. I was also handed a piece of Bazooka gum at the entrance to the hall.

At the event I discovered the musicians supporting Clapton in the group that evening.

There was a moment during “Why Does Love Have to Be So Sad” where I wasn’t wishing to hear “Badge” or anything else associated with Clapton pre-1969.

It was a psychic repertoire directive: A performer on stage really shouldn’t be exclusively beholden to their catalog or strictly dictated by their audience for past musical or recorded accomplishments.

I seem to recall there was a second show that night. The venue was half-filled, so the people in the balcony were invited to move to the front section for the nightcap.

Bobby Whitlock began his musical career as a teenager at the monumental Stax Records studio. His debut recording activity was hand clapping on Sam & Dave’s “I Thank You.”

Pop and R&B duo Delaney & Bonnie subsequently heard Whitlock perform at a club and invited him to join them in California and record on their record Home in early 1970.

Whitlock authored “Where There’s A Will, There’s A Way” found on Delaney & Bonnie & Friends On Tour With Eric Clapton.

After the other band members left to join Mad Dogs and Englishmen with Joe Cocker, Whitlock collaborated with Eric Clapton in England.

They played sessions together, most notably on George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass, where Whitlock and Clapton sang background (as the “O’Hara Smith Singers”).

Whitlock remained uncredited on All Things Must Pass, but provided pump organ (Harmonium), Electric Wurlitzer, Hammond organ, piano, and even tubular bells on certain tracks on the Harrison and Phil Spector production.

Songwriter Whitlock’s compositions have been covered by Ray Charles, “Slip Away,” Tom Jones, “This Time There Won’t Be No Next Time,” and George Jones, “He’s Not Entitled to your Love.”

Other recording artists have recorded his material, including Sheryl Crow, “Keep on Growin,” and Derek Trucks, “Anyday.”

In 2000 Bobby Whitlock appeared on the Jools Holland BBC-TV programme with Eric Clapton. In 2001 he played on the Buddy Guy album Sweet Tea.

Bobby Whitlock in 2011 published a book, A Rock ‘n’ Roll Autobiography with Marc Roberty that features a Foreword by Eric Clapton.

2010 Harvey Kubernik and Bobby Whitlock Interview

Q: What did you learn from hanging around Stax Records, the Records studio of Willie Mitchell or being at the All Things Must Pass recording sessions that you applied to the Derek and the Dominos sessions?

A: What I brought from Stax with me and Eric were the ‘white Sam and Dave’ vocals and duets. Everything was all about the music. It’s always been that way with me. Eric being a big star and all that never got in the way if our creative process. It was the same thing at Stax. Albert King, Carla Bell, Booker T & the MG’s. All of them big stars in my life and they were my friends. Steve Cropper and all those guys when I was growing up and making my bones in Memphis. It is not about the man. It is about the music. And that’s what I learned and brought along with me.

“Willie Mitchell at Hi Records was a good man. I knew him forever. I still remember exactly where his house is and all. He was just a real gentle man. He’d tell you and say, ‘I love the way you play, Bobby.’ Him bein’ a great keyboard player. Howard Grimes! Man, what a great drummer. He had a big thick snare drum and just laid into it with great big sticks. He was my favorite drummer other than Al Jackson.

Q: What can you tell me about what happens when Southern musicians met British musicians, as was the case when you recorded with Harrison and Spector for “All Things Must Pass.”

A: In my book I do a song by song breakdown of All Things Must Pass album. I tell who is playin’ what and who is singin’ what. Gary Brooker (of Procol Harum). He was the one guy who said, ‘You bloody Americans come over her taken our gigs.’ I said, ‘I’m not taken anybody’s gig, man. I am my own.’

Q: Talk to me about writing with Eric and your own tunes on the “Layla” album.

A: I lived with Eric for six months in England and the best part of a year with Jim (Gordon) and Carl (Radle). We were the house band, for sure.

“Eric and I had a relationship. A friendship and was real natural. It clicked and jelled. It was a natural thing that happened with a natural chemistry.

“I didn’t have to give much thought to writing. It just kind of happened. Before then I had written ‘Where There’s A Will, There’s A Way.’ That was my first rock ‘n’ roll song. I had written ‘Dreams of a Hobo’ and ‘Thorn Tree In The Garden.’ That was it. I had three songs under my belt. And some other things from when I was age 14. I did not think much about it. I just do these things. It comes very natural to me, like playing a Hammond B-3. Don’t think anything about it. Just something I do, kind of like walking.

“Songwriting is a natural part of me. Just like my singing of it is first. The only thought that I took from my writing of songs into the Derek and the Dominos was that I used to write ballads. And I always wanted to write a rock ‘n’ roll song and didn’t know how to go about it. And I asked Delaney once and he said, ‘all you do is speed up the tempo.’ ‘That’s it?’ ‘Yep.’ ‘I got it.’ Following off that I wrote ‘Where There’s A Will, There’s A Way.’

“I brought in ‘Thorn Tree In The Garden.’ I wrote that when my little dog went missing and Eric had heard it. And he asked me to do it.

Q: Eric Clapton has come out of Cream and Blind Faith, groups driven by virtuosos. It was made clear to you that the Derek and the Dominos band were going to be a group collaboration.

A: Yes. I wrote material in the band context and I write great songs for guitar players, you know. ‘Cause I write mostly on guitar. But when Eric and I got together we didn’t suddenly start playing guitar. We just hung out like a couple of best friends and had a cup of tea.

Q: No computers or tapes to assist the writing process.

A: No. (laughs). You didn’t put anything down like that. ‘I Looked Away’ was our first song. Eric had started with ‘Bell Bottom Blues.’

“He and I were talking once days and we said, ‘Let’s write it like a clean dirty song.’ And that’s when I came up with the idea of ‘Roll It Over.’ It clicked like that. Who wanted to sing? Who is supposed to sing? It came that way. He never told me what to sing and not what to sing ever. I just was able to step in and do what I wanted. Like, you know your part when you know your part, you know. Sometimes the best part is no part at all.

Q: There’s a song “Keep On Growing.”

A: It started out as a jam. Of course, we didn’t have tuning machines like you do now. And we didn’t have guitar techs taking our guitars and tuning them for us or changing our strings. Eric changed his own and tuned his own guitars. For the most part tuned it in front of the audience. And after each song we would have to tune up right in front of everybody. Whether it be The Royal Albert Hall or a Civic Center. That’s how it was then. We would do and jam, and then get into recording. We did not change our process when we got in the studio. We did not don ‘studio hats.’ We were still rock ‘n’ roll guys and we continued our thing. That’s why you have all these jams on ‘Layla.’

“So on ‘Keep on Growing,’ Eric wanted to put another guitar on it. I walked out of the room and he’s playing through a little Pignose. He put four of them on in layers. It was like the most incredible thing you ever did hear. The song, without the vocals is an incredible track. And then they were gonna can it! I said, ‘No, man.’ ‘Cause we didn’t have enough tracks for one album much less two. I took a yellow note pad and went in with a pencil to the foyer of Criteria Studio and all the words and melody just fell out. The story of my young life fell out in two and a half minutes. And I started to sing the first verse. And I got half way through it and asked Eric to come out and do our ‘Sam and Dave’ thing. And we did it.

Q: “Tell The Truth” has garnered radio airplay for five decades. It is one of the pieces on the Layla album as well as on live shows the band gave.

A: “Tell The Truth” is my favorite rock ‘n’ roll song. Duane had showed me all these open tunings. And Eric and I one day were sittin’ around his house and we were experimenting with open tunings. We had gotten to an open D and written ‘Anyday’ which is in an open D which is a different tuning than open E. We were messin’ around with tunings and I was tuning guitars to open C and F, and things like that and breakin’ strings front and center, you know. I had broken just about every string on every guitar at Eric’s house. That’s a lot of guitars and strings. And we were banging around all day playing with these different open tuning concepts.

“Finally, I landed on an open E, back you know where Duane had originally showed me and was piddling around with it. Eric went to bed. I was playing a bar across it and then I chorded the second change. It felt like a lick and a sound akin to what Keith Richard did with his 5-string guitar. So it had that sound about it.

“And I thought about Otis (Redding). ‘Tell the truth…’ All of a sudden I wasn’t tryin’ to rip Otis off or anything like that. I was just thinkin’ of Otis. And the sun started coming up off that beautiful countryside in that room and I started singing ‘Tell The Truth’ at the top of my voice. I got two verses and the chorus that morning at Eric. He had heard me singing through the floor. So he wrote the third verse through the floor.

Q: Then there is “Why Does Love Got To Be So Sad.”

A: That song happened when Eric and I were in the TV room, just him and I out there. We were talkin’ about girls, guitars and cars. When we comin’ to the woman part and he said, ‘Why does love have to be so sad, man?’ And I went, ‘Oh. Why does that have to be such a long song title?’ (laughs). And he started playing up on the neck of the guitar in a regular A Minor and I suggested he move it down on the neck and that’s when it started to flow. We were workin’ from the body of the guitar. It just gave the A Minor a different texture. It gave it an open droning sound.

“Not everybody then was into experimenting. Everybody wanted to play it safe. My whole life has been lived put of the box, you know. I have never been in the box at all. Thank goodness.

Q: Then there is the title track of “Layla.” Did you know it was a special song and destined for radio rotation, let alone inclusion in the album?

A: We didn’t think about it being like some sort of rock ‘n’ roll staple. That was just part of the stuff we were doing on our way on the road to play in the United States. It was gonna be part of our record. We knew that it was great music. All of our music was great music and we knew that too.

Q: Do you have a theory why this Layla album is so durable and has longevity?

A: My philosophy is that it’s not mine in the first place. It’s not me doin’ it, you know. I’m that place where the creative principal of the universe operates. Just like Eric is that place through which the creative principal of the universe. Call it God, Holy Spirit. Whatever you want to call it, he’s that place with the guitar and I’m that place with my voice and my playing abilities and my songs.

“And the thing is that if the song, anything, comes by way that divine source, it will have longevity. It will live its own life. ‘Cause you’re not cookie cuttin; it with a rhyme book from Nashville. Or you’re not trying to sit around and be clever, ever, and pull the lever, like Nashville. Cashville. Man…How that’s one?

“It comes from that divine source. You don’t have to worry about it. It is going to be a forever destination. It will be forever. Because you don’t have to worry about the money for it or if it is gonna be promoted right or anything. It will take care of itself. ‘Layla’ took care of itself. It developed its own wing and has flown all these years without anybody seekin’ a ton of cash.

Q: And the other cats in the band. Radle and Gordon, along with Duane Allman who joined on the sessions after the album had formally begun.

A: Carl and Jim…Didn’t get any better than that. The only other alternative was Jim Keltner. And that’s who should have been the guy and who was supposed to be the guy. But it didn’t turn out that way. He was busy.

“The rhythm section of Carl and Jim propelled the songs we put together. Jim Gordon is the most musical drummer I ever heard. All of the drums were in tune literally tuned to a key on the piano. Big kit. But Jim had this wonderful ability to interpret the nuances you could feel but not hear.

“Carl was solid as a rock. A downbeat player and right on it. So we have Carl who is solid and down and Jim who is up and on it. So it was perpetual motion.

Q: Then Duane Allman enters the picture.

A: It took it to a different level. Duane was a structured player. Everything the Allman Brothers did was structured and well put together and everything. And they played the same notes every night. Dominoes was not a structured situation. We were a free form rock ‘n’ roll band that was never the same with us. Ever. You might have something that resembled the hook line that wasn’t a sinker, you know. That’s what Eric does even today with ‘Layla.’ He plays the signature lick and that’s it. And he is off and running. He never plays the same thing twice. And that’s that free form.

“And Duane was structured. He came from the studio. He was a session player. With us he was a hired gun. And that’s not a negative thing, you know. And all these ‘Sky Dog’ lovers get all pissed off at me when I say he was a hired gun. He was a good one. I mean, a long time ago when they needed somebody to get the job done they had to get a hired gun.

“But Duane got us in a structured situation. We recorded the first three songs without Duane or anybody. We didn’t even know they were around. And we had already done the first three. You listen to ‘Keep On Growing,’ ‘Bell Bottom Blues’ and ‘I Looked Away’ and there is no Duane. And that would have been just as great a record without Duane. I am certain of it. Because Eric Clapton is the most competent guitar player that there is. And one of the finest slide players ever.

“The big difference would it have been had it not been Duane playing slide and Eric playing slide, it would have been in tune. Unfortunately, Duane played out of tune. I loved what he played but it was out of tune. Actually, there are two slides at the end of ‘Layla’ and they are both out of tune.

Q: You worked with Tom Dowd on the Layla album at Criteria Studios in Florida.

A: They had just got the big room finished when we went there. And it still had egg cartons on the wall for sound and hot sack hanging on the walls. James Brown had already recorded there and there was a gold album hanging on the wall which you can see in the fold out of the album.

“There was a row of airplane seats in the control room. Tom Dowd was in there. And he was at Stax and American Recording. I watched him record many times.

“In Memphis, if Tom or Jerry Wexler or Ahmet Ertegun was comin’ to town we knew about it. There was a buzz in the air, man. BW was gonna find out where it was gonna be and hang out with Ahmet, Jerry or Tom Dowd, getting’ my eyes and ears full.

“Dowd knew how to work with us which was to leave us alone. He came out and tried to put some number sheets on us and stuff like that. I told Eric we had to have a little talk. The word was that he was gonna stay behind the glass and be executive producer, because we already got it together and know the songs and all they gotta do it make sure everything goes down on tape and keep it running, you know. He did just that except for ‘Key To The Highway’ where he was off at the bathroom. We started playing ‘Key To The Highway’ and he come runnin’ down the hall, ‘Push up the faders!’ And that’s how it kind of glides into ‘Key To The Highway.’

“Tom was a great at bringing out the best because he set the artist up. Make it comfortable for you. ‘What can I do to make it right for you?’ Stay out of the studio? ‘No problem.’

Q: How does the new Layla album expanded reissue sound to you since you have heard it from vinyl to cassette tape to CD.

A: I love it. It is as if you had your ears stuck right in front of that little Pig Nose amp. That’s how good it is.

Q: The band attempted to do a second album. Let’s just say there was more than pouring Jack Daniels going down in the group.

A: There was a lot of paranoia. And that’s brought on by substance abuse. And we had been on this incredible tour and had done this incredible album, you know, and we come off the road. The band is so tight and we should have taken some time off. We didn’t.

“Lookin’ back, we should have not considered going into the studio. And really should have taken a good six month hiatus. Let everyone come down a little bit from the whole road experience. But that is not how Eric Clapton was operating at that point in time. He went from Cream to Blind Faith to Delaney and Bonnie into Derek and the Dominos. Boom, boom, boom. Without stopping. Here we had a hit record and my man wanted to stay home and do dope.”

Multi-instrumentalist Chris Darrow on Duane Allman.

“After two years in the Kaleidoscope I decided to leave the band for reasons of direction. While on my last tour with the band, I was in New York City playing at a club called The Scene. I was not sure what was next for me, and, since I was a husband and father, the possibilities of going back to school or finding a job seemed insurmountable at the time.

“The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band was in town and heard that I was leaving the Kaleidoscope. The Dirt Band was losing one of their core members, Bruce Kunkel, and was looking for a replacement. Jeff Hanna and John McKuen approached me about joining the band. I said to them that I wanted to attend a performance and then I would make up my mind. They had a concert at Hunter College on a co-bill with the Doors. I had had some contact with Jim Morrison in LA, so I felt good about seeing some guys from home and the possibility of work was encouraging for me too. Jim Morrison and I had a brief exchange before the show and then I saw the concert. The Dirt Band was great and I said ‘sure’ to their invitation to join and said I’d stick around for at least a year.

“The Dirt Band was like a family and was managed by Bill McKuen, John’s older brother. In addition, he managed other artists, Steve Martin, the Sunshine Company and the Hour Glass, a band from Georgia who later became the Allman Brothers. We all hung out a lot and, over a period of time, I became friends with most of the people in the bands, especially Duane Allman. He and Ralph Barr from the Dirt Band and his wife Holly were very tight. When I was in LA (I lived in Claremont), I spent a lot of time at their house and got to know Duane. Both he and Ralph were phenomenal guitar players and there was mutual respect all around.

“One night in early December of 1967 the Dirt Band had an interview radio show at a club called the Magic Mushroom, hosted by Phil Procter, of the Firesign Theater. I had a blue, 1954 Ford Tudor and had some room in the car for some riders. Duane wanted to come along for the ride.

“We all had heard earlier in the day that Otis Redding had been killed in a plane crash somewhere in the south. I will never forget Duane sobbing in the back seat of my car over the death of his ‘main man.’ I remember back to the time when I cried uncontrollably, after I heard about the death of Buddy Holly and Richie Valens. When our heroes go, what else is there to do?

“Duane and I kept in touch over time, even after I had left the Dirt Band. That’s when I began to tour with Linda Ronstadt, John Stewart and Hoyt Axton. In Linda’s band I usually roomed with Bernie Leadon.

“While spending a season in the New York area, we stayed at the Chelsea Hotel on 23rd street. One day I got an exited call on the phone. It was Duane Allman and he had just gotten his first National resonator guitar and he had to show it to us. He had gotten it at Manny’s, as I recall, and he was bursting with enthusiasm. Both Bernie and I were Dobro players and we all ended up sitting around with him taking turns, and talking about tunings and technique. Duane was already a natural slide player and he became a great player very fast. Maybe he knew intuitively that he needed get a lot down in a short time.

“Later, during the recording of Layla, he called to talk and he sounded pretty blown out over the phone. John Ware, the drummer in Linda’s band, and I were very taken by that record and I always thought that it was a pivotal, rising of the bar in rock and roll.

“Duane’s playing was searing and sinuous at the same time. His interplay with Clapton is mythic and the tonality of those sessions was raging. Had we known why, the sudden death of Duane would have made a little more sense. Hardly any of the Dominoes got out alive. That band entered a place that few can go and the attrition rate is high.

“Like a flame that burns hot and can burn itself out fast, Duane was a bright, burning star who went out way before his time.”

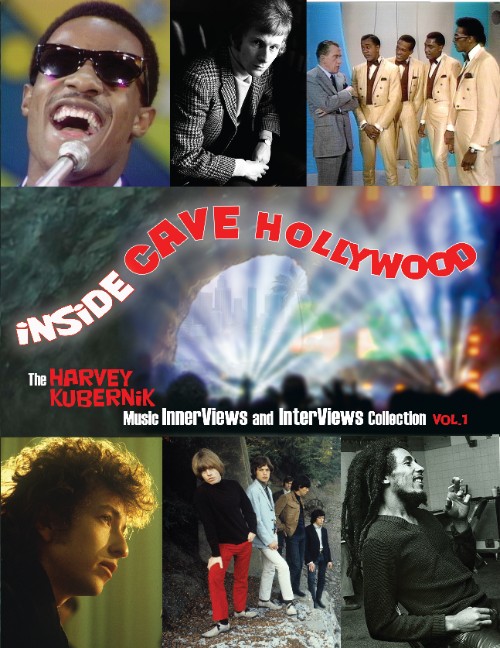

(Harvey Kubernik is the author of 19 books, including Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972. Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. For 2021 they are writing a multi-narrative book on Jimi Hendrix for the same publisher.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in July 2020 has just published Harvey’s 508-page book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters, featuring Kubernik interviews with D.A. Pennebaker, Albert Maysles, Murray Lerner, Morgan Neville, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, Andrew Loog Oldham, John Ridley, Curtis Hanson, Dick Clark, Travis Pike, Allan Arkush, and David Leaf, among others.

In 2020 Harvey served as Consultant on Laurel Canyon: A Place In Time documentary directed by Alison Ellwood which debuted om May 2020 on the EPIX/MGM television channel. It was just nominated for Three Emmy nominations.

Harvey served as Consulting Producer on the 2010 singer-songwriter documentary, Troubadours directed by Morgan Neville. The film screened at the 2011 Sundance Film Festival in the documentary category. PBS-TV broadcast the movie in their American Masters series.

Harvey Kubernik, Henry Diltz and Gary Strobl collaborated with ABC-TV in 2013 for their Emmy-winning one hour Eye on L.A. Legends of Laurel Canyon hosted by Tina Malave.

Kubernik’s writings are in several book anthologies, most notably The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski. He was the project coordinator of the recording set The Jack Kerouac Collection.

Kubernik penned a back cover book jacket endorsement for author Michael Posner’s book on Leonard Cohen that Simon & Schuster, Canada, will be publishing October 2020, Leonard Cohen, Untold Stories: The Early Years).