By Harvey Kubernik © 2017

Joni Mitchell Live Scheduled for 2018 release is a Murray Lerner documentary about Joni Mitchell, Both Sides Now: Joni Mitchell Live at the Isle of Wight 1970.

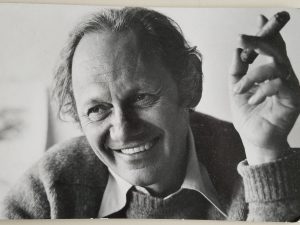

Oscar-winning filmmaker Murray Lerner passed away on September 2nd in New York City at age 90.

Born in Philadelphia Pennsylvania on May 8, 1927, raised in New York City, and a graduate of Harvard University English major in 1948, Lerner’s award-winning and trend-setting musical documentaries include examinations of Isaac Stern, Miles Davis, Bob Dylan, the Newport Folk Festival, the Moody Blues, Jimi Hendrix, the Doors, Jethro Tull, the Who and Leonard Cohen.

Scheduled for 2018 release is a Lerner’s documentary about Joni Mitchell, Both Sides Now: Joni Mitchell Live at the Isle of Wight 1970.

Also allegedly readied for February 2018 is Lerner’s complete one-hour film of the Doors’ set at the 1970 Isle of Wight.

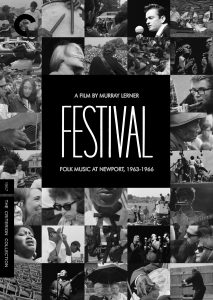

On September 12th, Criterion will release a director-approved special edition of Festival! It’s a new reconstruction and remastering of the monaural soundtrack utilizing the original concert and field recordings and presented uncompressed on the Blu-ray DVD.

The disc will also feature When We Played Newport, a new program incorporating archival interviews with Lerner, music festival producer George Wein, Joan Baez, Judy Collins, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Pete Seeger, and Peter Yarrow. In addition, there’s also a new feature Editing Festival, with Lerner, associate editor Alan Heim, and assistant editor Gordon Quinn.

There’s also a selection of complete outtake performances, including Clarence Ashley, Horton Barker, Johnny Cash, John Lee Hooker, and Odetta. Package booklet text has an essay by critic Amanda Petrusich and artist bios by folk music expert Mary Katherine Aldin.

Over the years I interviewed Lerner a few times.

My brother Kenneth and I hosted a question and answer session with Lerner one evening in Hollywood at the American Cinematheque Egyptian Theater in August 2010 as part of Martin Lewis’ Mods and Rockers film series.

I cited Murray’s landmark movie Festival! in my 2017 book, 1967 A Complete Rock Music History of the Summer of Love. Lerner’s voice is also quoted in my 2014 book on Leonard Cohen, Everybody Knows.

In 2008 I talked to Murray by telephone about his The Other Side Of The Mirror-Bob Dylan Live At The Newport Festival 1963-1965 DVD released by Columbia Records and Legacy Recordings. Jeff Rosen serves as executive producer and filmed Lerner for a bonus feature interview contained in the package. Lerner’s Newport DVD premiered at the 2007 New York Film Festival.

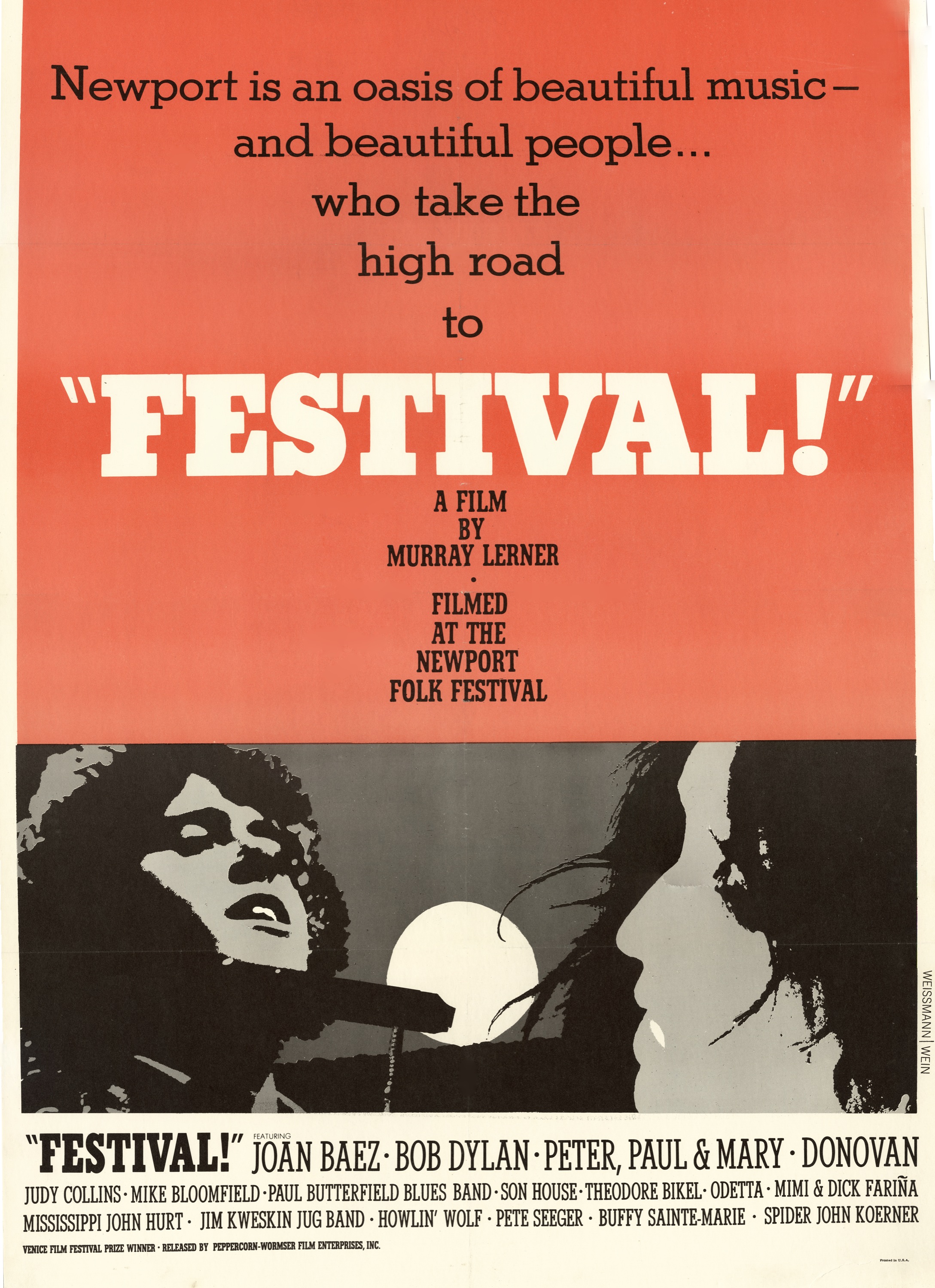

In 1967 Lerner’s documentary Festival!, lensed between 1963 and 1966 at the Newport Folk Festival, was theatrically released. The movie spotlighted performances by Pete Seeger, Bob Dylan, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Donovan, the Staples Singers, Judy Collins, Howlin’ Wolf, Judy Collins, Mississippi John Hurt, Peter, Paul & Mary, Johnny Cash, Son House, Mimi & Dick Farina, the Paul Butterfield Blues Band and Joan Baez.

This Oscar-nominated film was the first of the movie house documentaries on counter-culture music festivals, preceding both the Monterey International Pop Festival and the Woodstock Music & Arts Festival.

Festival! received honors at every major international film festival, including Manheim, San Francisco, Mar del Plata, and Venice. It was distributed on DVD in 2005 by Eagle Rock Entertainment.

Murray Lerner’s filmmaking career began from “industrial cinema.” In 1980 he produced and directed the Academy-Award winning From Mao To Mozart: Isaac Stern In China about violin virtuoso Isaac Stern’s 1979 goodwill tour of Red China.

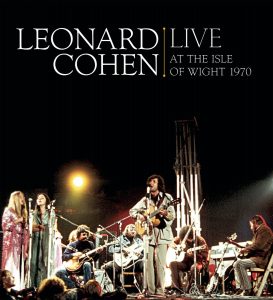

In 1995 Lerner released his long awaited Message To Love: The Isle of Wight Festival from 1970 featuring the Who, Jimi Hendrix, Leonard Cohen, Moody Blues, Tiny Tim, the Doors, Taste, Free, Jethro Tull, and other acts.

It’s a fascinating document of the plagued 1970 Isle of Wight Festival attended by some 600,000 people, the vast majority of whom refused to pay for their admission. A sophisticated analysis and look of the darker side of the period’s festival culture and location-dependent events.

Equally memorable are Lerner’s fully realized and updated stellar documents of the complete performances, Listening To You: The Who At The Isle Of Wight Festival (1996), Blue Wild Angel: Jimi Hendrix at the Isle of Wight (2002), and Nothing is Easy: Jethro Tull at the Isle of Wight (2005).

Lerner produced and directed the revealing film in 2004 about Miles Davis, Miles Electric: A Different Kind of Blue, dramatizing the constantly innovative musician’s transition to his electric period. It earned the Canadian Banff Award.

In 2007 Lerner co-produced and was a director on Amazing Journey: The Story of the Who, that premiered at the 2007 Toronto Film Festival and debuted on cable television in November on VH-1. In November 2007 it was issued on DVD.

In 2009 I spoke with Lerner about his Leonard Cohen: Live at the Isle of Wight 1970.

Murray Lerner is the forgotten Godfather of outdoor culture music cinema let alone the singular force that shaped a new film genre who was still active in the frame game at age 90.

Lerner is the person who stuck both his neck and camera out for rock ‘n’ roll and in the process forged alternative screening outlets and distribution for his work which inspired film students, budding independent room workers and future moviemakers since 1967.

Producers and directors of music-driven documentaries hawking their wares owe both psychic and fiscal debts to Lerner’s trailblazing path that enabled music product screen exhibition over the last half century. Lerner taught at Yale and helped establish a film studies program.

In 1972 Lerner’s office sent me a single reel tape copy of Festival! to show to students at a rock music upper division literature class at San Diego State University. The first accredited course in the United States.

When watching and absorbing Murray’s panoramic musical library of moving images and icons, it’s quite obvious we always had a poetry head and storyteller for 50 years behind the camera.

Lerner loved folk music and literature, His life and career trek is a hydra-headed poetic and retail blend of Oscar Micheaux and Homer, four-walled by AIP’s James H. Nicholson, Samuel Z. Arkoff and Roger Corman.

His influential camera techniques and distribution outlets for his products informed all rock ‘n’ reel filmusic documentarians who followed, like Andrew Solt and Malcolm Leo who would produce and direct This Is Elvis and Imagine: John Lennon.

“Murray Lerner,” praised filmmaker Solt, “was a very interesting and important figure in visual music history!”

The Other Side Of The Mirror-Bob Dylan Live At The Newport Festival 1963-1965 is 83 minutes of filmed Dylan verbal and grammatical anarchy in chronological order, 70% available here for the first time.

It opens a window into a critical epoch in American cultural history as reflected in the musical transformations of Dylan’s watershed performances in 1963-1965 at the Newport Folk Festival. It’s a delight to check out Dylan from folkie to front man for the electric revolution of American Top 40 popular music.

The most extraordinary aspect is watching Lerner’s work capture this unbelievable moment in time where the young artist shows up from nowhere

then projects his own voice, his stage presence, his ability to deliver his art, but watching the audience’s reaction over the same period of time. As if everyone was in complete lockstep. That Dylan’s own personal growth mirrored the desire and the needs of an audience to have him there physically as well at the exact time. It was Dylan on the big screen just before both the distortion and benefits of fame.

A lone wolf himself, Murray Lerner visually is very sensitive to Dylan’s personal magnetism particularly that wonderful paradox of his assertive, even aggressive self-confidence combined with his physical presentation. Dylan on screen is a small delicate person but as soon blow you away as look you. Dylan’s uncanny abilities establish a compelling and distinctive vocal stylist.

The Other Side Of The Mirror-Bob Dylan Live At The Newport Festival 1963-1965 has no sense of director Lerner asserting a point of view of what this DVD means. It just gives you what happened. This is all the existing footage edited together to be as coherent as true to the moment as possible. Any dueling narratives between director and stage subject are not on display. Watch it and see what you think. Lerner captures the faction (fact and action) of Dylan’s seismic stage performances, especially the 1965 culture-shaping offering of “Like a Rolling Stone.”

Murray Lerner and Harvey Kubernik Interview

Q: Is there any sort of general philosophy that guides you in preparation of a documentary film subject?

A: I tend to make documentary films after thinking about it and researching it and having a concept in mind and finding iconic images that resonate with that concept. That’s the way I work. When it came to Festival! when I started to go up there and look, I went up for the Newport festival. I was a folk music fanatic.

Before then, I did some industrial films, an underwater feature, Secrets Of The Reef. It actually played in theatres successfully, at least in one theater, the Baronet, and then Jacque Cousteau came along with The Silent World and that was the end of our distribution. (laughs). We didn’t have any people in our movie. Ours was anthropomorphism and it was a negative word. I had done a number of industrial films with sophisticated photography and editing before I did Festival!

Q: This Newport Dylan DVD is a different sort of film, in a sense, from what you usually direct.

A: We decided on no narration, no pundit interviews, and no interviews with Dylan. Nothing except the experience of seeing him…That to me is exciting. Just the clear experience gives you everything you need. I felt that when I screened the music of The Other Side Of The Mirror, because his touted metaphorically as the mirror of his generation, and I thought no, he’s beyond that. He always takes the generation beyond that, and he’s like on the other side of the mirror, but I also felt the wonderous quality of his imagination took us like Alice to a new world on the other side of the mirror. I felt to break that would be bad.

Dylan’s songs and his ideas were so powerful that my thesis, or premise, was that once I got you involved in him and you were also seeing a change in his imagination going in his music that you wouldn’t want to leave it. Either I pulled you into it or I didn’t. If you weren’t pulled into his music and took this journey with him then you’re not going to like the film. Nothing you say is gonna make you like it more.

Q: Was it by decision you chose to shoot Festival! and The Other Side Of The Mirror Bob Dylan Live At The Newport Folk Festival in black and white?

A: I had a choice for black and white over color, and it was a major decision in the face of a lot of negativity. First of all, I thought at that time you could really get good color in the original but you couldn’t get good color duplicates. That the prints, which is, after all, that was going to be what you were going to show, and also the contrasts were too great, and the blacks wouldn’t have any detail in it. As a matter of fact, I was a fanatic about that, and I earlier had done an industrial film, which became a big hit in that industry, Unseen Journey, and I couldn’t stand the idea of Kodachrome prints, so I actually talked the people to pay to me to going to Technicolor, and doing three strip prints. And it worked. It was beautiful and I shot it in 35mm to begin with. But the 16 mm prints were also great, so I was really in to thinking about those things in a way.

I wasn’t influenced by any filmmakers, maybe Bert Stern and Jazz On A Summer’s Day, also shot at Newport in the late 50s, largely because of his use of telephoto lenses, which I fell in love with.

I have this theory. Color is perception but black and white is judgment. We see the world in color but the imagination does not necessarily work in color. And there is a sense that black and white as taking place in a way outside of realism. Since black and white never looks the way the world really is the conscious or unconsciousness comparison between the world that you see it and the way the world as it is in a color movie doesn’t ever happen. You don’t hold black and white to the same standards. There is an artificial, as in art element to black and white that separates it. The music is so colorful and powerful. Dylan’s 1963-1965 music was colorful, confrontational in a way, and with a tendency toward the mythic. Take me through the filming process?

A: Shooting Dylan in daylight, 1963 and ’64 is one thing, but 1965, evening, gives you a feeling of professionalism and not stardom yet, commanding an audience, whereas the other way he’s kind of part of the audience almost, you know. He’s a nervous flat-pick seeking youth, when you get to the black and white on stage. Because the lighting is more contrasty and so forth. I was able to listen to the music and see it as well. My thought about filming music has always been, or filming anything that has sound or motion, that you have to put yourself into it and then forget yourself, be part of it. I’m good at conversations and interviews. I’m a part of it.

At Newport we did pick up shots, we showed the audience and the community, because that was the relationship that we wanted to build up at that time. There was an audience involvement in this thing and there was a message of the audience that they were putting out. The basic thing is I become part of what I film. So it doesn’t matter what it is. Also, I’ve always felt, since I started film, that music should be the spine of a film. Not only music within a film but a musical structure for a film.

Q: How did you get the initial Newport gig that resulted in 1967’s theatrical release of Festival! which later utilized excerpts in your 2007 Dylan at Newport DVD item?

A: Through debt and through cajoling people to help. (laughs). There weren’t a lot of obstacles to shoot Festival! Once it got rolling then the obstacles were different people associated with the festival who had their own favorites to make a film. I had to overcome that. Anyway, I was determined to get it initially released theatrically. I knew there the workshops and live performances that were interesting and cinematic.

Festival! was released only theatrically in America in 1967 and not in DVD until 2005. The ‘Dylan thing’ began to grow on me.

As I thought about it, ‘What a great thing to see and to show the change and to show how he related to his own artistic development and consciousness.’ I felt it was one of those things I should just do. There is no way to describe it otherwise or prove how powerful it would be. So, I funded a draft edit myself, and took it some doing to find all this material in our outtakes, since they were very scattered, and I didn’t have much money when we made Festival! Then we had to rush to finish that film. You know, we might have a piece of one song in one place without the track, and a track in a third or fourth place. A lot of lip reading and eye matching.

We worked from a word print at that time and a little negative. Maybe 1973, ’74. For Festival! we had a crew of 3 and used Plus-X and Tri-X film. The rest of the crew used Arriflexes cameras I used an Auricon camera for several reasons. Once in a while I had to hand hold twelve hundred foot magazines, which is difficult. Another reason I used the Auricon was because we couldn’t do slating. We couldn’t synchronize it. Auricons could do single system sound. So, there is some sound on some negative. I thought of it a little later in the game but it was a clever idea, so it tells you where you are at with the camera.

Howard Alk my editor also worked on Dont Look Back with D.A. Pennebaker. Howard got it going. Howard was working with me when he had to leave to do Dont Look Back. Festival! was the first of those counter-culture music films.

And, music was always my passion for the soundtrack of a film. For the form of a film, when I did Festival! it was the form of the film should also be musical and it should be like experiencing a piece of music in addition to being about music. It seemed to work.

At the Venice Film Festival people in a 1,000 seat theater really got up and applauded. I was alone. I was brought up to think that things should be well exposed, in focus, and you can hear the sound. I had no encounters with Dylan except through Howard Alk. He was great. A marvelous human being. You had to stand up to him with a powerful personality.

So, every time I told him to change something, a storm would come over the room that we were in. But I stuck to my ground and that’s why he needed a director like me.

If you look at the editing of Festival! you will see how sophisticated it is. He’d carry over the tiny sound from one thing to another. It was a three picture two sound movieola and we spent most of our time repairing the film.

Howard called me up and said ‘why don’t we edit this in Woodstock?” and I said, ‘No!” ‘Cause I would have a lot of powerful voices around me. “How ‘bout Martha’s Vineyard?” It was edited for two summers at Martha’s Vineyard, then he saw a film I did about Yale, finish that. I had to deal with Albert Grossman for clearances. It took a while to convince Al who was not a control freak. Not the slightest influence in the editing. As time went on each artist was different. Dylan was a buddy of Howard Alk. Howard had their ear and a friend of Dylan, and had known Grossman from Chicago.

The concept was that going beyond the entertainment value of the music that was the music being used was a crucible for creation of a counter-culture and a message. The prize I got at Venice was not only for a form of entertainment but a means of an expression of youth. That’s what I wanted to do and look for stuff like that helped me do that. So, when I did an interview, I had that in mind. Like in the new Newport DVD and in Festival!

I interview Joan Baez in the car. She did a good one because she discusses what the kids ask. Joan could make fun of Bob on stage because they were close. I think they thought of themselves, and the crowd did as well as the king and queen of Newport. The movie I really wanted to make was about all the tension backstage from the other performers and managers. (laughs).

Q: Festival! was always well received when it played. Universities and midnight movie screenings.

A: It had more festival showings than any. San Francisco, Argentina, In Italy Federico Fellini the director gave me his phone number…but I never called him. I always admired him. I was rather shy at the time. At Venice, it sounds crazy, but there were a lot of big wigs there, Pasolini, Antonioni, my film was the most popular of the festival. It was a hit. [Receiving the San Giorgio Prize, an award from 1956-1967 to artistic works that contributed to the progress of civilization]

Festival! was not just about Dylan. They loved Baez and the rest of it. The whole crowd at Venice got up and danced in the aisles it was amazing. It was thrilling. It’s always been available for schools and screenings and before a Festival! DVD it was on videotape. I was determined not to let it die through mail order and schools. We never made any money. I was a terrible self-promoter and this was before DVD and cable TV.

Q: In Festival! and once again in the Newport DVD, the live footage of “Maggie’s Farm” was so powerful to see in a theater originally, and now on DVD. I dug seeing the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, too.

A: I knew the Butterfield band and had done some industrial film with some of their music. On stage Paul came alive. He’s not performing with Dylan together in the 1965 set because Paul mentioned something like it wasn’t right to have two stars on stage at the same time. I interviewed Mike Bloomfield in Festival! talking about (Paul) Butterfield. I wanted to show in the movie that this was a movement for white kids and white people to get into the blues. Bloomfield and Butterfield were iconic figures in my mind.

Q: You appreciated Dylan moving into electric rock ‘n’ roll from an acoustic setting.

A: I felt that electricity was needed to distribute the music in a wide basis, radio and television. Then, once it happened, the hunger for the feeling that electricity gave people listening to it was more than volume. I think electric music gets into your body, and enters into your nerves quite deeply, and almost puts you into a trance. It’s hypnotic. I’ve always felt this and this was the feeling I had when I watched Bob. And I was excited by it. I not only appreciated the changes I loved it! I really was mesmerized and hypnotized by “Maggie’s Farm” on many levels. As I was filming it I knew it was a gateway to a new culture in the form of based on the older culture, and I thought this was it.

I was mesmerized by electric music. By Paul Butterfield earlier in the thing and Howlin’ Wolf played with a band. But what Dylan did the electricity got into your bones. I was both in the pit and on the stage. In the DVD we didn’t use ‘Phantom Engineer’ (It Takes A Lot To Laugh A Train To Cry)” because I didn’t think it was up to the standard of ‘Maggie’s Farm” and “Like A Rolling Stone,” to be honest with you. ‘Stone’ is too big a climax to extend it with something not as good.

I knew it was going to be a major breakthrough. It was a mixture of booing, applause and bewilderment. I was intensely involved in the filming so I didn’t pay much attention to what the audience was doing. I was hypnotized in a way by the electric music and had to get the shot. And, the interesting thing about “Maggie’s Farm” which was a breakthrough musically, but the lyrics were expressing the same kind of idea that he wasn’t gonna be a conformist. And in a way, ‘Maggie’ Farm’ was a symbol for America working. We’re all working on “Maggie’s Farm.’”

Q: What impressed you the most about Dylan as a poet?

A: The words just fell on his music. I knew that when I saw him walk in a room at a party around 1962 for Cynthia Gooding. He came in and pulled out his guitar, played a few songs about New York, packed it up and split. He intrigued me. At Harvard university I majored in English and my main interest was modern American poetry. T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound. And their technique of two opposite symbols creating a third idea. Two different images, the unexpected juxtaposition of two different images for the third idea. Which guided me into filmmaking.

Q: What is the genesis of your Newport DVD?

A: Jeff Rosen loved Festival! ever since it came out and we became friends. He directed and filmed the interview with me in the Newport DVD. An associate of mine. He loved my Miles Davis’ film. How we got to the Dylan thing. Someone who shall remain nameless, an attorney I was dealing with in L.A. about the Isle Of Wight, saw some papers, turned out to be a Dylan freak, played the guitar, I showed him a copy of my work print from 1973, ’74, a draft edit, and told him not to ever show it to anyone because Dylan would be annoyed if it ever came out bootlegged.

Then, years later, Jeff Rosen called me up and said, ‘we’d like to buy your Dylan footage.’ ‘what do you mean?’ ‘I have a copy of this thing you did.’ I was annoyed. (laughs). But it turned out to be good. Jeff had a long range view of what turned out to be No Direction Home. I have some footage in No Direction Home which he twisted my arm to buy. (laughs). So, I said OK, “and he made a few good suggestions, but it had to be released after No Direction Home. I was at time in conflict licensing things from my work. Absolutely. Always in conflict. (laughs). What did happen when I revisited it I saw I had a real film there. Not just a series of shots. But in chronological order. Once the New York Film Festival took it I knew I had a film.

Q: What was the one thing you learned from your Newport documentary which you applied to the Isle of Wight shoot?

A: First of all, on the technical side, I learned and made sure everyone examine and perfect their equipment so that they were sharp to be on a very literal level. Sharp when they were close in and wide angle. Very often when you go to a wide angle it can lose focus. So I had them check their cameras for that problem and fix it. And, going from there, I had to call them all together and explain what I don’t like. I don’t like, and some of them did it anyway, I don’t like fast pans, fast zooms.

I said, “If you are panning over to a musician that is playing but you don’t see because he comes in after the musician is on go slow.” You’ll hear the person and it will be more dramatic than if you swish the camera or zoom in. That is one of the big things. And, I ‘Close Up! Close Up! I don’t mind looking into the lights for effect. A bunch of stuff I directed them to do. I took special shots, positions.

Like with the Doors, I took the shots from behind looking into the lights. The idea is to be musical in the movements and try and move with the music.

When I showed some films a few years ago in Hollywood at the Egyptian Theater, the Who at the Isle of Wight, Andrew Loog Oldham was there and commented, “You were part of the band.” That’s what you gotta do.

I personally have a technique where I practice the choreography of the camera. Everyday for about an hour before I shot, having an assistant stand by and I would focus, zoom and figure out how big the moves had to be to get the result I wanted so I could do it myself. And I practiced all of that. And I kind of instilled that sense that of the choreography of the camera being part of the concert. For the most part, in the planning stages, I picked positions to shoot. And I told people, “You concentrate on the close up and you concentrate on something else.”

Q: Your Message To Love music documentary shot in 1970, thankfully released commercially in 1995, included the Who’s cover of Mose Allison’s “Young Man’s Blues” and Townsend’s “Naked Eye.”

The DVD also birthed a retail relationship with the band that exists at the moment with the release of the Who’s Amazing Journey 2007 documentary that you’ve co-produced and co-directed.

But, there was like a 20 year period, before the Betamax and VHS-formats, the growth of home video market, and the DVD as a viable format where we could not find your catalogue and music documentary products, largely because the market had not been developed yet to distribute your things. Man, talk about being early on the scene. Message To Love emerged as a joint venture with Castle Communications and BBC in association with Initial Film and Television.

A: (laughs). The thing that got me re-introduced known again, was my Isle of Wight Feature that took a long time to get made. Dylan had played at the 1969 Isle of Wight festival, not at Woodstock that same summer.

Bert Bock was the agent got him to go. Bert was sorta acting as Dylan’s manager at the time, not Albert Grossman. The Foulk bothers were looking for a performer a headliner for my film. Bock was a great fan of my Newport film. And he called would you like to rent us the Newport film to show at the Isle of Wight? I responded and suggested, “Why not make another film?” OK. That was part of it. And, actually, they did license my film, and if you watch my film once in a while there are two big projectors sitting there. (laughs).

What happened at that festival was you couldn’t show a film because there was chaos. I did get a check but it took four months to bounce. (laughs). In those days the English currency regulations were such you weren’t allowed to send money abroad except under certain conditions. I decided to shoot Isle of Wight in color and duplications of color were OK.

I predicted what would happen. Conceptually, I thought the counter-culture, having followed it, was being co-opted commercially, kids were getting angry and I knew there would be tremendous tension and anger. I knew it was brewing, and one of the people interested in it was in England. I got an English crew of about 9. After I did it, and Howard helped me edit a little initially, a “demo” reel, but then he moved to the west coast to live on Dylan’s property editing Renaldo & Clara. It was really exciting.

Everyone loved it but wouldn’t back it. They didn’t think the music would sell they didn’t think the political aspect would sell. But I knew the Who, Jethro Tull, Miles Davis, the Doors were potent performers on stage and on camera. Absolutely. And, there was a feeling “Oh well. These are older acts.” Which I never agreed. The people who control this media they just say…

Looking at the Who through a lens was incredible. We all felt it was almost a religious experience. You’ve seen my Who film from the Isle of Wight. That was really incredible. And the crowd was with it, and of course, except for me, the crew was British, and they knew their music quite well. I had a great chief camera man. Nick Noland, an incredible find, another one like Howard Alk. He did a lot with the counter-culture.

And Jethro Tull lept off the screen with “My Sunday Feeling.” I finally got to put their full set out from the Isle of Wight a couple of years ago. I interviewed Ian Anderson 30 years later, a land squire, still a musician. I’ve done a number of interviews, like with Ian, and the people who played with Miles Davis at Isle of Wight, 30 years later.

The Message To Love festival film documentary was both a harder and easier sale. I got the financing from a fellow Jeff Kempton who followed the production many years from Castle to Eagle Vision. BBC put up half the money. Initial Films for BBC to do it. They didn’t bother me at all. It took a lot of money on my part to keep showing this demo reel of the Isle of Wight. (laughs).

I remember Haskell Wexler, a friend of mine, he said, “I’ll tell you what. I’ll talk to you but you’ve got to promise never to mention the Isle of Wight again. (laughs).” That was then. It really was an interesting journey. It ended up being the last live performance of the Doors. The mood of it. I had met (Jim) Morrison before, and he said, “you can film but you’re not gonna get an image because we keep the lights low.” “I’ll get an image.” (laughs). I pointed toward the light. It was very simple.

From the Newport festivals on I decided I wanted to show something behind the scenes in the music business. Not just the festival, because I saw the festivals were not quite as loving and peaceful as it seemed. Every night there would be big meetings at Newport until two or three in the morning arguing about who was gonna be next and the order of the lineup, all of that. And you never saw that and I was startled. How many blacks? How many Appalachian singers? This and that. So I decided I would like to turn the cameras the other way at some point. And then when I saw Woodstock, I decided I had to because I thought it was phony. So that made me determined to do it.

And then by chance, really, when (Bob) Dylan was breaking up with (Albert) Grossman, and Bert Block, who became an agent for (Kris) Kristofferson, at the Isle of Wight festival, he came to me. He had been Grossman’s partner and now was with Jerry Perenchio’s Chartwell Artists) He liked my movie Festival! He said these the promoters from England came to America and asked him to get the performers for the 1970 Isle of Wight, an island off Southern England. They wanted to run and screen ‘Festival.”

So I said fine, ‘But I’d really like to make a film.” OK. That started me down this path. And they did make a deal with me to license “Festival.” They even rented two projectors and in the Tiny Tim scene you can see them. They had rented the projectors but the guys in charge fled, they were really afraid of staying in the festival grounds ‘cause they were worrying about the atmosphere. They refused to work it. So they gave me a check for licensing which took at least three months to bounce. That was the first one. It was organized by Ronnie, Ray and Bill Foulk, and Rikki Farr (compere) did the stage introductions.

I decided to do a film and the promoters I got them in touch with ABC Films at the time and they decided it wasn’t a good enough deal. So then we started to negotiate and talk. Everyone wanted to do this film and they were willing to do it with me. And I organized an English crew. And I had one person from staff, a guy who had been my assistant on a lot of shoots.

I had a loose outline between the idealism of the music and the commercialism of the music business.

In the 2007 Who documentary, I conducted the new interviews with everyone. Pete Townshend is not only bright, but perceptive, and he’s thought a lot about issues that I’ve thought a lot about, the meaning of rock ‘n’ roll. Anyone who thinks about it has to think, ‘why is this so powerful?” ‘Why do millions of people respond to it all over the world.’ And then the bigger question I ask people I want to make a film about is “what is music?” That really throws people when I ask them that. Why is it so powerful? And Townshend realizes that the audience is part of the music. At least that’s the way he plays and they play. He doesn’t speak the way you want him to. I mean he can throw you! (laughs).

Q: Your films on Bob Dylan and Miles Davis are time capsules. Dylan at Newport before he went electric was like Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz before the road became color. Before it was post-War America, where nothing had sorted itself out yet, by the time Dylan went electric, everything changes. Between 1963-1964 people started screaming for him. The electric set demonstrates paramountly that Dylan was his own man. That he was not going to wait for anyone.

It reminds me of the famous line by Miles, that my brother Ken told me, when someone came up to Miles and said ‘I’ve grown up with your music and now that you’re playing this electric stuff I just don’t get it.” And, Miles looked at him and said, ‘what do you want me to do? Wait for you?”

That’s what great artists do by definition. They’re not being held back by their audience.

A: In my Miles Davis film, I thought the change in Miles Davis was very similar to the change in Bob Dylan and the hostility that he encountered as for them going electric. Because of Dylan, and I read a lot about Miles going electric, it took a lot of courage on his part to go electric. That music at the Isle of Wight was cinematic, Like Dylan earlier at Newport. Dylan was at the absolute height of the involvement and the charisma. Absolutely. Of course he has words and Miles doesn’t. It’s a big difference for me. Shooting Miles I knew I had an important moment, especially in a rock music setting. That’s the point, again.

Q: You have a Hendrix Isle of Wight title I’ve always liked. What was the magic of this guy on film or the amazing qualities he had? I have a theory some of it had to be because he was left-handed and we see your film different.

A: (Laughs). No one has ever said that and you might be right. That’s interesting. I have to think about it. I felt that the thing about him was that I felt he was talking through his music. His music talked to us. Those were his lyrics in a way. His narration. And he was talking to us through music. And he was expressing himself that way. He wasn’t just accompanying a song. He was unusual and so intensively evolved. It was incredible. The volume of the sound.

Q: And, there is also Leonard Cohen: Live at the Isle of Wight – 1970. A full-length DVD out in 2010.

Q: And, there is also Leonard Cohen: Live at the Isle of Wight – 1970. A full-length DVD out in 2010.

A: I shot color for the Cohen and the Isle of Wight performers. It was high-speed Ectochrome reversal. And I’m glad I did it because the color lasts a lot better in reversal. The camera people I had were with their own cameras for the most part but they used Arriflexes, and the clas and a new camera, the main camera man used an Aaton, a kind of avant garde camera at the time.

Q: The Isle of Wight footage and the Cohen section you seem to capture close ups and focus on the dramatic aspect of faces, Cohen, some band members, female background singers is terrific.

A: Yes. I always use very very long lenses as an adjunct to my photography. I believe in the long shot because I would like the thing to feel musical and not jumpy. I think film is visual music. And it should be, and I believe in editing that way. You can moments where you are doing quick montage. Most of the time you need to relax.

I like really long and before anyone ever did it I used 2,000 millimeter lenses and for crowd shots, moving in slow motion on Broadway. A lot of unusual stuff. I love people coming towards the camera and coming into close up. And then I got a 600 millimeter lens for my 16 millimeter camera, played around with it during Sonny Terry and Brownie McGee at Newport. Real close ups.

Q: At the August 31, 1970 Isle of Wight music festival on a small island off the southern coast of England Leonard Cohen was billed with Miles Davis, Joni Mitchell, the Who, the Doors, the Moody Blues, Jethro Tull and Jimi Hendrix. But the crowd, alas, had its own agenda, metastasizing into a heaving, barreling beast, crushing the gates and fences, rubbishing the prim seaside community.

The throng numbered 600,000 and Cohen was at the epicenter of the event which now had fire and smoke encroaching structures and equipment. When Cohen and his band, which included Bob Johnston and Charlie Daniels, finally took to the stage, it was two o’clock in the morning.

My brother Kenneth Kubernik described the scene remarkably well after viewing your Leonard Cohen Live at the Isle of Wight-1970 DVD in my book on Leonard, Everybody Knows.

“The punters, restless in the aftermath of Jimi Hendrix’s incendiary performance, were instantly tamed by this unkempt, unprepossessing gentleman, adorned in pajama bottoms (he’d been having a nap backstage and barely answered the bell to perform). As poised as Caesar before his legions, Cohen took command of his ‘Army’ – his group’s nickname – and held the half million attendees in thrall.

“Documentarian Murray Lerner captured it all on film. The resulting 2009 DVD – Leonard Cohen Live at the Isle of Wight – 1970 – demonstrated his gift for conjuring magic out of mayhem. The oft-derided listless baritone voice, the plodding rhythms and the deathly pallor of the lyrics conspired to produce a hypnotic calm.”

A: I first heard Cohen as a literary character, a poet. And then in the late sixties a couple of his records on the radio. I heard his debut LP. He came out acoustic and walked out with guitar.

“I felt hypnotized. I felt his poetry was that way. I was really into poetry and that is what excited me about him. To put music to poetry was like hypnotic to me.

When he told the audience before a number, how his father would take him to the circus as a child. He didn’t like circuses, but he liked when a man would stand up and asking everyone to light a match so they could see each other in the darkness. ‘Can I ask of you to light a match so I can see where you all are?’

But when he sang the lyrics of the songs they took over and he had ‘em in the palm of his hand. Even removing myself from being the director how this guy could walk out and do this in front of 600,000 people? It was remarkable. It was mesmerizing. And the banter was very much in tune with the spirit of the festival. And, more particularly what he said, you know. ‘We’re still a weak nation and we need land. It will be our land one day.’ It was almost biblical.

When he did ‘Suzanne’ he said, ‘Maybe this is good music to make love to.’ He’s very smart. He’s very shrewd. The other thing he was able to do, the talking, I think the audience was able to listen to him. They heard him and felt he was echoing something they felt. The audience and I were mesmerized. It was incredible and captivating. That night, Leonard was on some sort of mission. His band was called the Army.

My film shows the roles of the background singers. Sure, Ray Charles and Raylettes, and the Cohen singers had beautiful skin. They were a balance to him up there and the fact I was jealous of the guy that this guy was able to get all these women. (laughs). And he’s up there very late at night, the morning, unshaven. The music is great.

The Isle of Wight journey was worth it. That was the most exciting event I’ve ever been to. ‘Cause it was so all encompassing. And new. In terms of the possibility of the crowd killing us and always living on the edge of that precipice.

And I was always thinking, in relationship to the performers, ‘What’s my role in what they are singing about? How do I fit into that?’ I change with each one as I am watching them. Like with the Moody Blues, I liked their music. It was different and interesting, and like Leonard Cohen, it had an undercurrent of mysticism to it.

I thought the Isle of Wight1970 and the Cohen footage had touched the deep chord of people. I realized how deep it was and I was startled how prophetic it was. I was proud and excited at what I had done.

I’ve gone to some Cohen concerts over the last twenty years. Really incredible. It was hard to believe it was the same person. The songs hold up. I was really excited he was so good. I really was. His talent hasn’t diminished, especially in terms of songwriting.

On stage I thought he was overdoing it in terms of his own energy. But there’s a mysterious quality to it and we don’t really know why it works. I just thought it’s amazing and I like some of the songs and some of them I had not heard. I really liked it and said to myself it is amazing he can still be doing this. He knows what he is doing and you do sense, when I went to the Beacon and Radio City Theaters, you sense there is a kind of formula to what he was doing. That part was not as good. His so called off the cuff remarks were the same at both.

Isle of Wight, Leonard was much different than Miles, Jimi, the Doors and the Who. Because the talking on stage was very insightful of him, you know. He must have understood that by talking and speaking to them it gave him, or put him in touch or gave him a kind of camaraderie with the crowd that no one else tried to do. Maybe he felt he needed it and he may have.

Leonard also had that fabulous guy, the producer who was in his band, Bob Johnston. I had quite a time over decades later getting him to be interviewed for the DVD.

All performers have a common thread of some kind or they wouldn’t perform.

A: Leonard, on stage and in film is different than Bob Dylan.

Q: Can you compare and contrast them

A: If I can. Dylan depends on music in a way that Cohen doesn’t, I think. It stands on its own more than Dylan does, I think. Dylan is brilliant. I trust in a sense whatever he says. He actually likes to tour and he likes the involvement with the crowd. You never know what he really thinks. He loves teasing people.

Q: What about Joni Mitchell from Isle of Wight?

A: I’m very excited about the possibility of the Joni Mitchell one. The whole set. I’ve been dealing with Elliott (Roberts). There are a few more Isle of Wight things I’d like to do. Like the Doors.

Q: What is happening with the Isle of Wight Doors’ footage? Their last live show.

A: I’ve just licensed “Break On Through” for a Doors’ compilation, Re-Evolution. I’ve tried to put out the Doors’ set. It was dark but that was the mood. And the darkness is interesting I think.

Morrison said to me, “You can film but you’re not gonna get an image but we’re not gonna change our lighting.” “I’ll get an image.” I did.

I met and knew (Jim) Morrison earlier at the Atlanta Film Festival. I was showing “Festival,” it won an award and they had a film [Feast of Friends] they had made played. We talked at the party afterwards, we had both won awards but they were bullshit awards. Mine was for the best music. What does that mean? At the party and I really gave it to the organizer out loud a hard time, told him what I felt about him, and they came up to me and said, “We agree with you.” I got friendly and tried to help them distribute their film.

Q: You have witnessed and participated in the development of the rock and music documentary over 50 years. Like D.A. Pennebaker. Have you done panel discussions with him in front of film students? I’ve been attending some of these events, and unlike the sixties and seventies, most of the students and wannabee filmmakers in the audience at the question and answer session now want to know about royalty points on the back end of movie deal and not curious about film stock, lenses or concepts to creating a story.

A: The best one of those was at the Santa Fe New Mexico Film Festival. A documentary panel. Pennebaker was there. (Ricky) Leacock was there. I was there. It was a seminar type thing where people would question us afterwards, you know. It was all about how do you get the money? Not about creative stuff but financial. One kid said to Pennebaker, “How do you get the money to finance a film?” And without missing a beat he said, “Marry a rich woman.”

Harvey Kubernik is the author of 12 books, including Leonard Cohen, Everybody Knows, and Neil Young, Heart of Gold. In April 2017, Sterling published Kubernik’s 1967 A Complete Rock Music History of the Summer of Love.

Harvey Kubernik’s literary music anthology Inside Cave Hollywood: The Harvey Kubernik Music InnerViews and InterViews Collection, Vol. 1 will be published in late 2017, by Cave Hollywood. Kubernik is also writing and assembling a multi-voice narrative book on the Doors scheduled for publication last quarter 2017.

In November 2006, Kubernik was invited to address audiotape preservation and archiving at special hearings called by The Library of Congress held in Hollywood, California.

During July, 2017, Harvey Kubernik was a guest speaker at The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame’s Library & Archives Author Series in Cleveland, Ohio discussing his 2017 book 1967 A Complete Rock Music History of the Summer of Love.