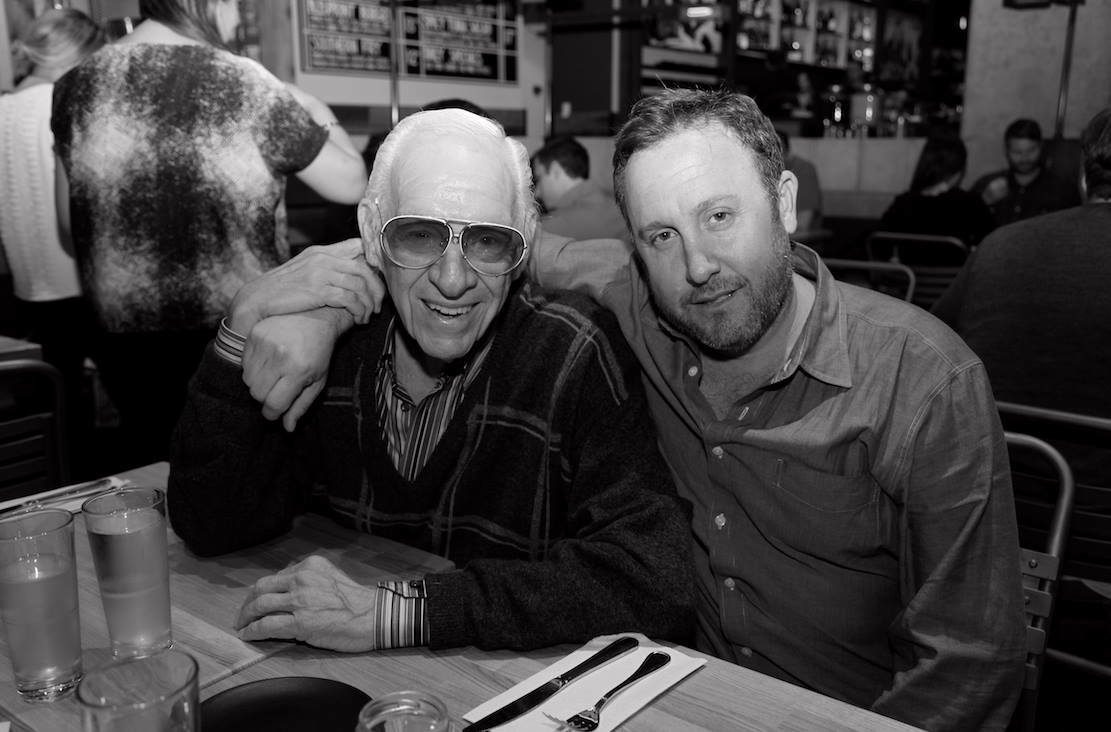

By Harvey Kubernik c 2016

Visionary booking agent and artist manager, Jerry Heller, who served as N.W.A.’s manager, who in the mid-

1980’s at Macola Records in Los Angeles, where he first met Eazy-E (Eric Wright) and helped launch Ruthless records in 1987, N.W.A.’s Straight Outta Compton was released in 1988, has died at age 75 from a heart attack in Thousand Oaks, California.

Heller’s half a century show business legacy will be primarily defined by obituaries, mixed tributes and uninformed eulogies, along with the circulated myths by the music media about his retail influence on rap music, plus his seminal stint and combative split managing N.W.A. and subsequent depiction in the 2015 Straight Outta Compton biopic.

I’ve interviewed Ice Cube three times in 20 years and know all about his song “No Vaseline,” directed at Heller, and Dr. Dre’s video “Dre Day, taunting Heller and Eazy-E. I’ve been in a room at Studio One with Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg but don’t look to me to chronicle ancient rap wars.

H.W.A. and Bones Thugs-N-Harmony were also artists on Wright and Heller’s Ruthless label. Heller’s nephew Terry also signed a group Will I Am formed. Their completed album was never released owing to Wright’s death. Three years later Will I Am formed Black Eyed Peas.

One thing is for certain: Jerry Heller’s 50 year impact on the music business is monumental. He developed touring acts and helped a lot of major players in the music industry gain entry level positions.

Music industry executive Irving Azoff, who represents major artists including the Eagles, knew Heller for decades. Heller gave Azoff his first job in California.

In a statement issued by Heller’s publicist, Azoff commented about Heller’s death.

“Jerry was an incredible talent. And it was unfortunately often unappreciated talent,” added Azoff, “Jerry reinvented himself, over and over, and he was always on the cutting edge,” Azoff reflected. “Jerry, more than anyone, taught me to care about my artists.”

As far as Heller’s detractors, stated Azoff, “As can be expected in Hollywood, and especially, in the rap business, there is a lot of acting going on.

“I knew Jerry, as well as anyone. Many unfairly maligned him. I know the Hollywood version was not true. The negative depiction of him was entirely fictional. However, those that really knew him know otherwise.”

In 2006 Jerry Heller’ Ruthless A memoir, written with Gil Reavill, was published by Simon & Schuster-Simon Spotlight Entertainment.

After N.W.A. Heller became involved in a record label that issued Latino and hip hop rap discs called Hit a Lick.

Jerry Heller was born in Shaker Heights, Ohio in 1940. After serving in the Army and earning a business degree in 1963 at the University of Southern California, Heller orked in Los Angeles and Beverly Hills as an agent, tour manager and music promoter in the 1960s and ’70s.

He began his career at Coast Artists, Associated Booking and Chartwell. He then opened the Heller-Fischel Agency.

His clients over the decades included Otis Redding, the Standells, Grass Roots, Marvin Gaye, Lou Rawls, Van Morrison, Elton John, Pink Floyd, Guess Who, Canned Heat, Eric Burdon and the New Animals, the Who, Ike & Tina Turner, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Black Sabbath, Humble Pie, Styx, Journey, Carly Simon and Cat Stevens.

Heller’s role in introducing touring artists in the U.S., including Elton John’s debut at The Troubadour, while helping birth festival music culture and stadium shows from 1966-1976 is undisputed.

“I was improved by being in the room with him,” offered author, record producer, disc jockey, and former manager of the Rolling Stones, Andrew Loog Oldham. “I had paws-he had wings.”

“About 1961-62 I met someone who would believe in me – start to book my band – and be my friend for over 55 years. His name – JERRY HELLER. .” Volunteered noted Record Producer Michael Lloyd.

“ I woke up today to learn that my friend had passed. Words cannot properly describe him. He was the true Superagent. He was the cofounder of Ruthless. He was an innovator. But mostly…..he was my friend. My true friend. He was always trying to find more, new things that we could do together.”

“Music is not as sweet today….. it’s lost an icon, a legend, a friend.I know that we will see each other again and you’ll show me the ropes and be eager to book me…I pray for all of God’s blessings to be on you my sweet friend.Thank you God for loaning Jerry to me and to the rest of the world. He was respected. He was appreciated. He was loved.

I will miss him so very, very much.”

In 2007 I interviewed Jerry Heller about the 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival and some encounters he had with Hendrix, Redding, Joplin, Lou Adler, Bill Graham, and Albert Grossman.

Q: At Monterey you were the talent agent for Canned Heat, Eric Burdon and the Animals and Otis Redding.

A: It was the first festival I had gone to, but I had been dealing for a couple of years with Claude Nobbs at the Montreux Jazz Festival and George Wein at Newport when I worked at Associated Booking in Beverly Hills.

“I was handling Otis Redding and just met him through Phil Walden, a colorful character, who was his manager. Good guy.

“Lou Adler and John Phillips pretty much dealt with managers and artists direct as it was going non-profit, so they really didn’t want to deal with agents. Several agents went to Monterey. Phil was a fabulous manager.

“I had never seen Otis live before only on film from the Olympia Theater in Paris. He was a big man. He was like Aaron Neville. He could just blow you away with his sheer power and intensity of his voice and his lyrics. I’ve never seen anything like it at Monterey. The reason I was at Monterey with Otis was that I said to Joe Glaser. ‘This guy can be a major, major pop star.’ This guy can be a big rock ‘n’ roll star.’

“After Monterey I called Bill Graham and we made arrangements to play a number of dates. The promoters Wolf & Rissmiller in L.A. and guys all over the country who were my guys to play Otis. I was also going to get him real money. We were really positioning him. But remember, he had already done the Olympia Theater in Paris, the Stax/Volt Revue in Europe, and look at the hits he had written already.

Q: Jimi Hendrix made a big impression on you at Monterey.

A: But for me, Jimi was beyond belief. Already there was abuzz about him and he was just unbelievable. So much so, I bee lined right after his set I talked to him, because I had heard about him from some of my friends in England, and I talked to him, and told him I was gonna arrange a tour for him.

“One of the biggest mistakes I ever made in my life…So he said, ‘Who you gonna have me play with?’ And I wanted to put him in the biggest venues possible, and remember, I don’t even know this guy, and had him then open for the Monkees at the Hollywood Bowl. I booked the date. I wanted to get him exposed to as many people possible.

“I liked Chas Chandler. He was a good guy. I knew the Animals and Eric all the way back to the Michael Jeffreys days. So, I did have an entry, and worked for the mob then, and always had that kind of cache. I thought Eric Burdon was great at Monterey. He had ‘Sky Pilot’ and ‘San Francisco Nights.’

“I saw Hendrix over the years because of my relationship with Eric Burdon, and with Steve Gold and Jerry Goldstein of War.

“Jimi Hendrix blew my mind but the group that stole the show was the Who. And they went to Woodstock two years later. The only thing I didn’t anticipate was that they (Pete Townsend) could write something like Tommy. I mean, I knew this group was very special.

Q: Didn’t you know Janis Joplin?

A: Every time I saw Janis she blew my mind. I didn’t think anyone could sing like her. And she was so tiny, and you don’t realize how tiny she was with all her little feathers and stuff. Janis drank like a man out of the bottle. I saw her do a sound check at the Hollywood Bowl drinking a bottle of Southern Comfort. Man, but when she started to sing…

Q: What has been the influence and impact of the Monterey International Pop Festival on outdoor music gatherings that followed?

A: If Monterey taught us things, it was things that we learned from it that we adapted to the real world. Remember: it was a non-profit, and those of us on a different level said ‘OK. Why can’t we do this and make money?’ That’s why it’s so important because it showed that people could get together and that it could be peaceful and nice, black and white, English and American, northern and southern, and everything just worked and all we really had to do was adapt the financial aspect of it to the 1969 Newport Pop festival at Devonshire Downs in Southern California and it became a huge profit kind of venture.

“The influence and impact of Monterey impacted other festivals that followed. I represented Eric Burdon and maybe even Paul Butterfield at that time, or a bit later. Also Lou Rawls and I know I represented Moby Grape.

“There’s one thing that people forget about Monterey that is an astonishing fact. And, the more that I think about it the more it astonishes me: I mean, look at what that festival did. The impact Lou Adler has had on everyone’s life.

“Dig this, man. There were only 7,000 people there each day. Sitting in chairs! Wow! It is mind boggling that this festival, where people played for no money, in a day when Bill Graham was transforming the industry from a bunch of hippies into legitimate businessmen.

“What Monterey did was awaken a whole generation of dope smoking hippies to the fact that music could be big business. At the festival you had label heads, a few agents like myself.

Q: The agent function changed and the manager became more important in the music game following Monterey.

A: And managers like Albert Grossman and David Geffen. I really didn’t know anything about Laura Nyro. First of all, she was known only as a songwriter, really in those days. And wasn’t really known as a performing artist. But David Geffen zeroed right in on her, and Clive (Davis) zeroed in on her.

“I remember when Grossman confronted Geffen at the Troubadour in the back of the alley. Grossman started blathering about Nyro’s overseas publishing rights as he backed Geffen against the wall and started to threaten him.

“I told Grossman ‘to cool it. It’s not happening, Albert. You better catch him in an alley in New York because this is our town.’

“Albert was the first really important personal manager. I remember Grossman from Monterey and knew him very well.

“Here was a guy with great talent he represented. He had good instincts for that. That doesn’t mean that he represented them well. He just had great instincts for talent. Bonnie Bramlett used to carry around a picture of Albert in her wallet that she used to take out all the time when Albert had short hair and was a CPA. That’s how he started out before he has a pony tail and long hair. This guy was a CPA! He was a superstar and always in a position with somebody who was very powerful. He knew had to wheel that power.

“I think that Monterey said to the suits ‘This is the future. You guys better get on the train or you’ll be back releasing records by jazz acts.’ And the funny thing is, like the guys who were successful at Monterey like Clive, Mo Ostin, Joe Smith, Jac Holzman, guys like that, to this day are still the most important guys in our business.

“So, Monterey not only was a springboard for acts but a springboard for executives. And, up to that point the agents were the power. You had to have relationships with agents but after Monterey you had agents leaving with their acts to become managers, like Skip Taylor with Canned Heat. They were leaving to start their own management firms. So, what it did was start an era of cooperation between agents and managers that really hadn’t been up to that point.

“Remember: up to that point the first three agents in America were two fight promoters and an eye doctor. So we had Joe Glaser with Louis Armstrong, Willard Alexander with Woody Herman, and of course, Jules Stein.

“If Monterey taught us things, it was things that we learned from it that we adapted to the real world. Remember: it was a non-profit, and those of us on a different level said ‘OK. Why can’t we do this and make money?’

“That’s why it’s so important because it showed that people could get together and that it could be peaceful and nice, black and white, English and American, northern and southern, and everything just worked and all we really had to do was adapt the financial aspect of it to a music festival Newport ’69 in Northridge, California Devonshire Downs and it became a huge profit kind of venture.

“After Monterey not only were there changes in logistics, artist fees, but the type of promoter that then was coming in to do these shows.

Q: The festival culture booking mentality really changed once 1969 started.

A: I was ground floor on the whole Newport ’69 thing. I booked half the acts. I got to know these two promoters. Two months before Woodstock. Two years after Monterey and the acts are not doing it for free anymore, and that lead into sound and lights. So it complicates matters. Plus, everybody saw the problems Lou Adler had with the film rights. All of a sudden all the agents were saying we have to get all these rights up front. It was a very complicated negotiation now. Acts are now being represented by more sophisticated entities. Artists were getting paid more.

“I think at Newport ’69 held at Devonshire Downs in June 1969, the promoters paid acts in advance. Devonshire Downs was a really good festival. We set up headquarters at the Holiday Inn a few blocks away in Northridge, and had limousines that took people back and forth, a big tent set up backstage.

“I also did a favor for managers Terry Ellis and Chris Wright who had Jethro Tull and they were worried about having to play to an empty field after Creedence Clearwater Revival headlined, who were my act.

“Bobby Gibson, my friend from 1963 at USC, and who did the PR for the Cheetah Club in Venice, came up to me at the Devonshire Downs festival. He was doing Tull’s press, ‘Look man, if Creedence goes on everybody is going to leave. That’s who they are there to see.’

“By then there was fixed billing and fairly rigid order of appearances because normally Creedence, who headlined that day had their choice of when they wanted to go on. The prime time was right after sundown before the audience was burned out. Because they had been out in the sun since 10:00 a.m. Jethro Tull was on their first tour.

“So I went to talk to John Fogerty in the Creedence tent, and discussed our business relationship since I was leaving Associated Booking, and I tied him up long enough for Jethro Tull to play a 30 minute set. That’s the way it goes. And, I did the right thing. And that was OK.

“Woodstock in August 1969. Lou Adler was a little older and his friends were guys like Clive Davis. Mo Ostin, Herb Alpert, Jerry Moss, and they like a nice place to stay.

“By the time Woodstock came around, you’re talking about guys having to walk 7-10 miles just to get to the fields there. And guys like Mo Ostin aren’t gonna do that. By that time, they had guys under him from the [Warner/Reprise Records] office, and some of the guys from other labels never really liked rock ‘n’ roll.

“Woodstock was a springboard for the economic base of the music business. Ironically, Woodstock, even more ironically, set the bar so impossibly high for everybody else. Then the business transformed from a win/win situation where everyone made money and everybody did well, even with a low ticket price.

“What it did was people became involved with things just because they were large investments, and the music that became secondary. Then independent promotion men get involved who are the focus of breaking records and millions of dollars in investments.

Q: Can you comment on music and culture after 1967 Monterey.

A: Look at Monterey and the era. The war in Vietnam amping up. 1968 the deaths of both Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr., the Chicago Democratic convention ’68, SDS, Mario Savio, the Weathermen. We’re talking about the Black Panthers and the Diggers. We have this incredible frame of reference for people to write and to do and to feel and to be activists. There’s no activists anymore.

“It’s all about how many fuckin’ trucks you got to go on the road with. And who gets to use the sound and lights. It’s just not like that anymore.

“And, Bill Graham was responsible as anybody, even though he was an incredible dichotomy. We were great friends. And love hate relationship. He could do sound better than any soundman, lights better than any light guy. Catering. This guy would help you carry a Hammond B-3 organ up two flights of stairs because your roadie didn’t show up. Later in the mid ‘70s and late ‘70s he moved into stadiums with A Day On The Green shows in the Oakland stadium with 7 acts and 50,000 people.

“This decade I teach a music class at UCLA, and I always say there are three things that as a manager or a record executive look for in an artist: One is they have to be unique. When you hear Bob Dylan sing, you don’t wonder who it is. When you hear Joan Armatrading sing, you know who these people are.

“Another thing is if you do it first, that’s always good. Three Dog Night sang other peoples’ songs. And the other thing is that you gotta do something better than anyone else does it. With all the great guitar players in the world I just can’t think of anyone who surpassed Jimi Hendrix. I mean this guy was astonishing.

(Harvey Kubernik has been a music journalist for over 44 years and is the author of 8 books. During 2014, Harvey’s Kubernik’s Turn Up the Radio! Rock, Pop, and Roll in Los Angeles 1956–1972 was published by Santa Monica Press.

In September 2014, Palazzo Editions packaged Leonard Cohen: Everybody Knows, a coffee tablesize volume written by Kubernik, currently published in six foreign languages. BackBeat/Hal Leonard Books in the United States.

Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik wrote the text for photographer Guy Webster’s award-winning first book for Insight Editions published in November 2014. Big Shots: Rock Legends & Hollywood Icons: Through the Lens of Guy Webster. Introduction by Brian Wilson.

In March, 2014, Kubernik’s It Was 50 Years Ago Today The Beatles Invade America and Hollywood was published by Otherworld Cottage Industries.

In November of 2015, Back/Beat/Hal Leonard published Harvey’s book on Neil Young, Heart of Gold).