By Harvey Kubernik c 2016

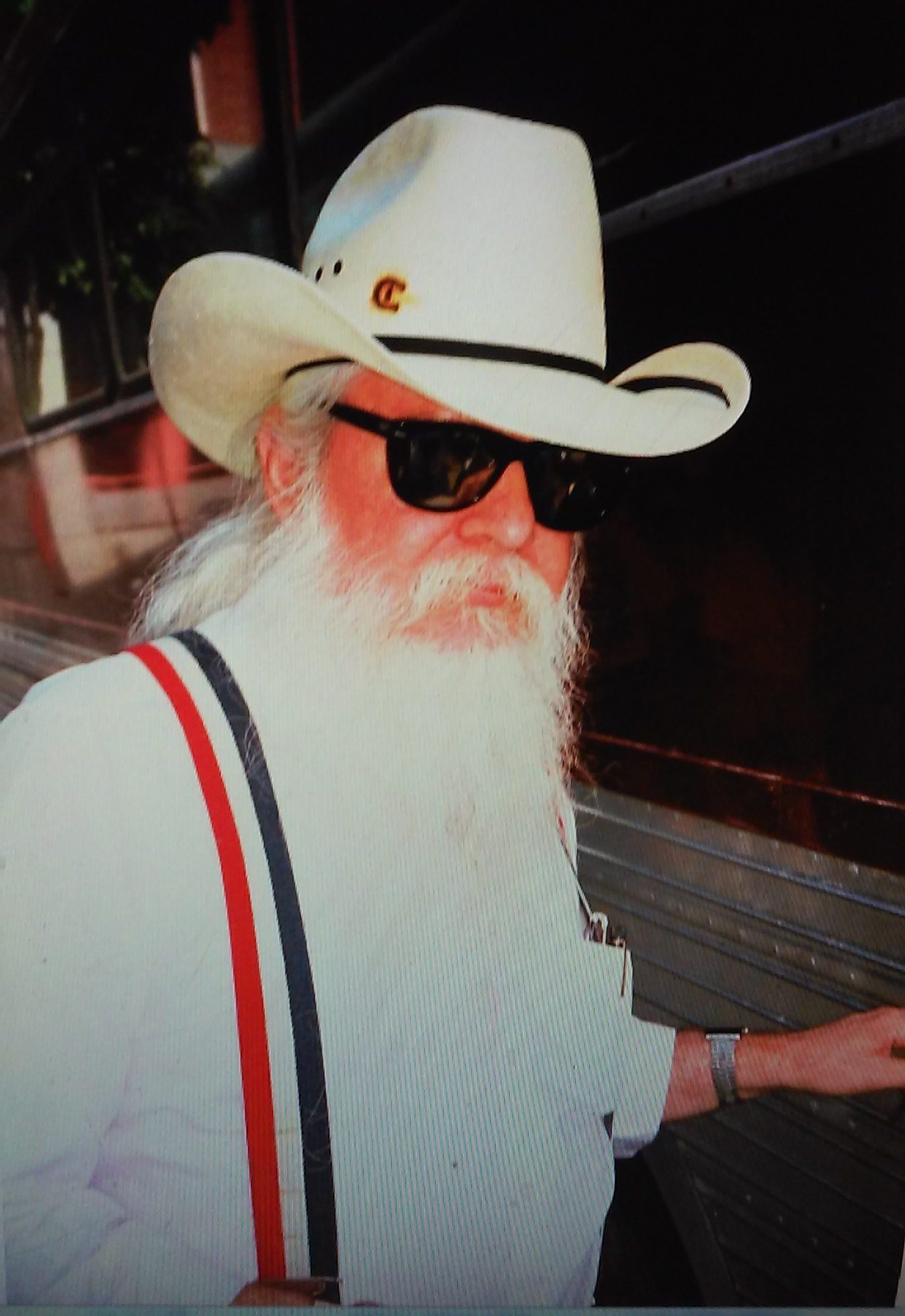

Multi-instrumentalist Leon Russell, the former Claude Russell Bridges, left the physical world on November 13th, dying of a heart attack in Nashville, Tennessee.

I met Leon in 1978. I spent six weeks at his Paradise recording studio in North Hollywood. There were times during sessions where he had a typewriter on top of a keyboard and would write a lyric on the spot. I later learned Leon was a onetime state typing champion in Oklahoma. During breaks we would talk about records he guested on or tunes he penned for the Carpenters, Joe Cocker, Bob Dylan and Gene Clark. Some tracking and overdubbing on Love’s Forever Changes was done at his home studio in 1967.

My friend, journalist Michael Macdonald worships Russel’s arrangements on the Clark and Gosdin Brothers’ collaboration, Echoes. Leon played piano on a project I produced.

I felt it was very appropriate to offer a tribute to “Brother Leon,” who played keyboards on many inspirational and landmark West Coast recordings with guitarist Barney Kessel, father of David Kessel, guiding light of the Cave Hollywood portal.

Over the decades I asked three musicians about Leon Russell’s highly influential piano and songwriting abilities: Jack Nitzsche, Jim Keltner and Ian Hunter.

“I met him [Leon Russell] with Jackie DeShannon; she introduced me,” remembered arranger, composer and record producer, Jack Nitzsche to me during a 1988 interview published in Goldmine magazine.

“Leon at the time was playing piano in a bar in Covina. He was an innovative piano player. He was good. I heard him on a Jackie DeShannon record. In those days it was real hard to find rock ‘n’ roll piano players who didn’t play too much. Leon talked the same language. You could really hear Leon play in the Shindig! TV band. I put him in The T.A.M.I. Show band, and he’s all over the soundtrack.

“During the [Phil] Spector sessions, a lot of the time we had two or three piano players going at once. I played piano as well. Phil knew the way he wanted the keyboards played. It wasn’t much of a problem who played. Leon was there for the solos and the fancy stuff, rolling pianos. The pianos would interlock and things would sound cohesive. I knew Leon would emerge as a band leader.

“I didn’t have to do a lead sheet for ‘He’s A Rebel,’ just the arrangement. I put the band together for the session, a lot of the same guys I had been working with for years. Phil didn’t know a lot of these people: he had been in New York in 1960-1962. Leon Russell, Harold Battiste, Earl Palmer, Don Randi, Hal Blaine, Glen Campbell: A lot of the players came out of my phone book. Phil knew Barney Kessel. At one time he had taken guitar lessons from Barney, years before.”

In my 2014 book, Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop, and Roll in Los Angeles 1956-1972, I spoke with noted drummer, Jim Keltner, about Leon Russell.

“I joined Gary Lewis and the Playboys after ‘This Diamond Ring’ put them on the map. I played on the next single and album, and then did a couple of tours.

“Snuff Garrett from Liberty Records made me shave my mustache and get a professional haircut. Then he took me to meet Leon Russell at the studio. Leon was raised in Tulsa, and I loved that, because that’s where I was born. I didn’t realize I would be following in the footsteps of the great session studio drummers Earl Palmer, Hal Blaine, and Jim Gordon.

“Leon was the first record producer and arranger I ever worked with. I was very fortunate to have him as the first producer I came in contact with, because Leon always had a slightly different musical angle that he came from. I think Leon was always looking for something a little bit out of the box. I didn’t know that at the time. Hal Blaine was there, by the way. I thought he was there to play tambourine, but in actual fact, Hal was there just in case I couldn’t cut it [laughs].

“At the beginning of the Gary Lewis ‘She’s Just My Style’ recording session, Leon said, ‘Don’t play any fills. Not even one fill.’ And I understood that instinctively. I thought, ‘This is the way rock ’n’ roll singles are made.’ He asked for a fill just at the beginning, and I did. Then he said, ‘Can you do that backwards?’ And I thought, ‘Oh yeah. I can do that. That’s cool.’ So I played the fill backwards, and opened the hi-hat in the intro. He liked that a lot. So right away, we made a connection there. During the playback, he turned to me and said, ‘You’re gonna be a great rock drummer.’

“I remember, at that moment, I felt a real confidence. Right around that time, I had begun to realize that playing rock ’n’ roll was not just for morons. You really had to know what you were doing.”

In a 2011 edition of Goldmine magazine, Keltner earlier reflected on Russell to me.

“When I got to know John (Lennon) he told me he liked the Delaney Bonnie and Friends Accept No Substitute album. George Harrison had actually tried to sign Delaney and Bonnie to Apple Records in the U.K. Leon is all over that. His piano playing on the ‘The Ghetto’ is the greatest. No one else can do that.

“At the 1971 Concert for Bangla Desh, Leon Russell made it great to be there. I had played with Leon on quite a lot of stuff: Gary Lewis and The Playboys, Delaney & Bonnie and Friends, Joe Cocker and Mad Dogs and Englishmen.”

“I just love Leon’s piano playing on that first Delaney & Bonnie and Friends LP,” volunteered saxophonist Bobby Keys one evening backstage at a Rolling Stones’ concert at the Staples Center in Los Angeles.”

And, during a 2011 interview with Ian Hunter, bandleader of Mott the Hoople, we also discussed Leon Russell’s impact on his very late sixties’ recordings.

“On our [Mott the Hoople] first tour of America around 1969 I really discovered and got turned on to Delaney & Bonnie and Friends, especially Leon Russell. My thing was Leon. That movie, Mad Dogs and Englishmen. Leon got a lot of slack from tour and film because people kept saying he was trying to put (Joe) Cocker away. I don’t think Joe was that fit and healthy at that time, and Leon was really doin’ the business.

“The piano playing… ‘In The Ghetto’ was the first time I heard Leon. It was on an album. I just couldn’t believe it. It was Gospel Rock. It was unbelievable. And I know where he got it from, like Dr. John and a couple of other people. But for me the style of playing. I went home and tried to do that for months. I tried to learn that song for months. I got near it but never got it right. The feel.

“When we started there wasn’t any keyboards other than piano and organ. We didn’t have these little keyboards that now can do everything. And if you wanted piano and organ at the same time on a track, you couldn’t get a guy with his left hand on one keyboard and his right on another. You had to get a piano player and an organ player. So then you had the piano and organ color. And then you had all the different guitar colors. And it was also extremely powerful. Like ‘Ballad of Mott.’ Some of those songs we would take ‘em down to zero and all of a sudden BANG, the whole lot would come in. It was easier to put dynamics in and drama, and beautiful, quiet stuff too. Sustaining stuff. Some things a guitar can’t do. It’s just that fraction too jagged. There’s a smoothness with a piano and an organ.”