By HARVEY KUBERNIK C 2018

Before playing its final show on May 5, 1968 at the Long Beach Sports Arena in Southern California, Buffalo Springfield released three studio albums on ATCO during an intense, two-year creative burst.

on ATCO during an intense, two-year creative burst.

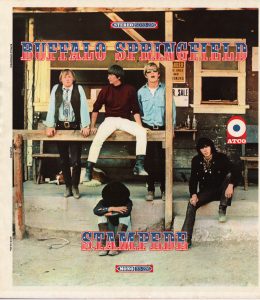

Those albums – Buffalo Springfield, Buffalo Springfield Again, and Last Time Around – have been newly remastered from the original analog tapes under the auspices of Neil Young for the new boxed set: WHAT’S THAT SOUND? THE COMPLETE ALBUMS COLLECTION shipping from Rhino Records on June 29th

The box set includes stereo mixes of the group’s three studio albums plus mono mixes for Buffalo Springfield and Buffalo Springfield Again. There are also CD and limited-edition vinyl sets.

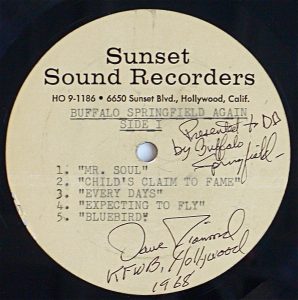

So to acknowledge the 50th anniversary of Buffalo Springfield’s last appearance, and Rhino’s target retail launch date of this package, earlier this decade I had asked some friends who attended that memorable event. Chris Darrow: (Musician): By 1968, they had a number of hits with Still’s ‘Bluebird’ and ‘Rock and Roll Woman’ and Neil Young’s ‘Mr. Soul,’ as well as ‘Expecting to Fly’ and ‘Broken Arrow.’ The band had some tension among the members, both personally and musically, and began to go in opposite directions. I went to their final concert on May 5, 1968 at the Sports Arena in Long Beach. The set was long and intense and ended with a long 20 plus minute version of ‘Bluebird.’ Country Joe and the Fish and Canned Heat were also on the bill.”

Rodney Bingenheimer (Deejay): I went to Buffalo Springfield’s last concert in Long Beach. Neil was back in the band. I really liked drummer Dewey Martin and at the gig he dedicated ‘Good Time Boy’ to me. I was on the side of the stage and it was the best time I ever heard the group live. I was really sad when the band broke up. I was bummed out when I heard Buffalo Springfield was ending.”

Rick Rosas: (Musician) Mark Guerrero and went to the goodbye concert in Long Beach. It was pretty heavy. I was so young. It was really good. Some of the guitars were out of tune.”

Mark Guerrero (Musician): I saw the Buffalo Springfield’s farewell performance at the Long Beach Sports Arena May 5, 1968. It was a great show with one of its highlights being a hot version of ‘Uno Mundo,’ but it was sad to know it was the end of the road for the band.”

Denny Bruce: (Record producer/manager): I went to the last Buffalo Springfield concert in Long Beach. Neil [Young], Jack [Nitzsche] and I had a limo. Jimmy Messina came home with us. His head down and crying, ‘I can’t believe it’s over.’ It was a sense of relief for Neil. He was glad it was over.”

I witnessed Buffalo Springfield live on stage during December 1966 at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium and The Hollywood Bowl in April 1967

Their three 1966-1968 albums were always debuted over the Southern California airwaves before the rest of the world discovered them. You really had to live in Hollywood then to further understand and comprehend the initial impact of these regionally-birthed discs and artwork design. Thankfully, I was there.

I’m delighted Buffalo Springfield’s era-defining body of work will be heard and discovered by new ears globally. I’m sure WHAT’S THAT SOUND? THE COMPLETE ALBUMS COLLECTION coupled with my published navigation, 2009’s Canyon of Dreams: The Magic and the Music of Laurel Canyon will be examined, spurring additional interest for documentaries that will be produced and products still inspired by my teenage neighborhood. At Fairfax High School in West Hollywood our Driver’s Education class was held in Laurel Canyon and adjacent Mt. Olympus. Try learning how to parallel park while “Nowadays Clancy Can’t Even Sing” was on the radio station KHJ play list.

If you want to really learn something new about Buffalo Springfield and their audio legacy also check out my 2015 coffee table size book Neil Young Heart of Gold, currently published in six foreign language editions. It truly offers insights and revealing never before published observations and authentic accounts of the band’s potent 1966-1968 existence.

I’ve always felt the Byrds, Buffalo Springfield, and then The Band, were the joint Godfathers of Americana music.

WHAT’S THAT SOUND? THE COMPLETE ALBUMS COLLECTION will be available on June 29 from Rhino as a five-CD set for $39.98 and will also be on digital download and streaming services. High resolution streaming and downloads will be available through www.neilyoungarchives.com.

The albums will also be released – for the first time ever – on 180-gram vinyl as part of a limited-edition set of 5,000 copies for $114.98. The 5-LP box features the same mono and stereo mixes as the CD set, presented in sleeves and gatefolds that faithfully re-create the original releases.

WHAT’S THAT SOUND? THE COMPLETE ALBUMS COLLECTION is available, this time around, chronologically and sonically improved from the label’s 2001 Buffalo Springfield Box Set product, but the fan boy in me wishes the longer 9:00 minute version of “Bluebird” was included. It’s only available on a double vinyl LP Buffalo Springfield package that was released in 1973.

So enjoy these Buffalo Springfield 2018 available recordings on compact disc and vinyl, as well as digital downloading, before record labels like Rhino cease pressing up hard product and become exclusively streaming services.

“In our world of music in 2018,” poses author Jan Alan Henderson, “has any new product stood the test of time that this Buffalo Springfield box set will? Golden years, golden days as Mick Jagger and Keith Richards put it, ‘Lost in the silk sheets of time.’”

“Sure, this was one band who boasted within its rarefied ranks several musical characters of superb pedigree indeed,” realizes Gary Pig Gold …who, for the record, may never have visited Springfield but has been stranded in Buffalo several times. “Yet despite the fact that a failed Monkee and even a couple Au Go Go Singers were on board, I have for a half-century-and-counting insisted it was the presence of not one, but TWO certifiable Canadians that truly gave this band its shine, its sharpness, and undoubtedly a big part of its unmistakable sound …even on the stereo mixes.

“I speak, of course, of (a) Neil Young, of whom little if anything need be added at this point, but especially of the (b) as in bassman – and so much besides – Bruce Palmer: Already by ’66 a veteran of more spectacular Toronto-area rhythm ‘n’ Merseybeat combos than even young Neil could’ve shook a Gretsch at, Bruce brought the incredibly innovative bottom he’d already punched onto such woofer-blowing discs as Jack London & the Sparrows’ ‘If You Don’t Want My Love’ (REQUIRED LISTENING, everyone!) to create the beyond-solid foundations his Buffalo bandmates relied to create upon and, yes, were expected to fly fully from.

“One could argue the Springfield was never the same – some might even say never completely recovered from – the loss of Palmer; not to mention the here today, maybe here tomorrow ways of his fellow Canucklehead Neil. But all great art, even pop (music) art, seems to burst best from turmoil, and that the Springfield always had in often self-defeating abundance. They ‘burned’ briefly, but oh, so brightly! As all the best herds, then and even now, seem to.

“They came, they played, and they crumbled. Fifty-some-odd years gone. But still as sound as ever.”

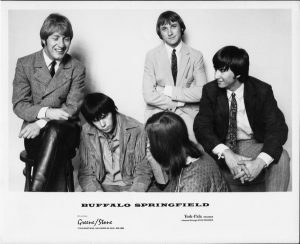

Stephen Stills, Neil Young, Richie Furay, Bruce Palmer and Dewey Martin played their first show together as Buffalo Springfield in 1966.

Dickie Davis: (Road manager I was involved in starting the Monday night Hoots at the Troubadour. I sold tickets. In 1965 I lived in a tiny apartment on Fountain Avenue. Over the telephone Stephen Stills said, ‘We have to go to the airport. I have this guy coming in from Ohio who I’ve sung with before and I think we can make it work.’

“At the time I was doing lights at the Whisky a Go Go. So I was connected on Sunset Strip and the Troubadour on Santa Monica Boulevard. We picked up this guy Richie (Furay) from the airport. Stephen is very intuitive. He can see where something is going and get there before you realize he wasn’t there already. He’s good. We called him a genius then. He has flashes of this. Richie had short hair. Richie could sing with Stephen and they sounded good. And Richie also looked up to Stephen to the extent it was necessary to get along with Stephen. Richie is great.

“Stephen and Richie meet Barry Friedman [publicist, deejay and early Buffalo Springfield mentor], and then stay at his place. They saw the value of Barry because he was a wheeler and dealer. Barry is a friend of mine, too. Neil and Bruce come into town and I hear about it. Stephen and I remain in touch. Stephen and Richie play with a drummer, Billy Mundi. They were good. Later they meet Neil and Bruce. And Bruce was a phenomenal bass player. Talk about keeping time and not caring about time. Finding it again when it mattered. I was immediately sold.”

“In 1965 I met Neil Young for the first time in New York,” Furay recalled in a 2015 interview we did. “Back then, he was a hungry guy. He was there to peddle songs. I had him put ‘Clancy’ down on tape I was so enamored with that tune that went from ¾ to 4/4. Oh my God. This is like incredible. Neil was the funniest guy in the world. Neil and I have always had a good relationship. I’ve never had a problem. I was frustrated with him, in and out, you know. ‘We’ve got a band here!’ But, he’s always been straight up. Look: You either love the guy or you don’t love the guy. He marches to his own drum and that’s him.”

Dickie Davis: I’m watching Steve, Neil, Richie and Bruce, Billy Mundi, and at this point Barry asked me to help out with the band. Sort of like a road manager thing. Stephen, and I believe, Richie, come to my house and ask me to be involved. ‘I want you to stay involved with the band.’ Barry has been managing the band, helping them out, feeding the group and clothing. After that I get a call from Barry: ‘The band really likes you and we will make a place for you.’ Barry had seen it grow. ‘We’ll work together and split everything six ways until we can find you a real manager.’ And that was our handshake deal. Either before or after Dewey Martin joined as drummer.

“Dewey was from fuckin’ left field in this band. He was a country western drummer and a showman. He could hold a beat, though he rushed. He was an excellent addition to the band but he was nothing like any of the other people in the band. They already had the name when Dewey came to his first rehearsal. When Dewey walked in, Neil pointed to the sign on the wall and said that was the name of the group. As for the name Buffalo Springfield, I liked the idea. It had a contemporary, sorta Jefferson Airplanish sound with strong All American/western implication.

“There was magic at the rehearsals. My first impressions of Neil Young at Buffalo Springfield rehearsals? He seemed shy. He seemed anxious to please and he seemed like he really knew how to play guitar. He played maybe a very Chet Atkins country style rock ’n’ roll but if asked he could adapt his playing. If someone said, ‘Give a surf run, Neil,’ he would do it like the Ventures. Nothing to it.

“I helped it happen at the first gig at the Troubadour. It took so long to set the amplifiers up the audience had lost interest. And it took them a while to get the audience back. But they did. There was a good reaction. I was around when Chris Hillman said to Stephen he could get them into the Whisky a Go Go. I was in the room or told instantly. He really did talk to Elmer (Valentine] and said ‘you should hire this band.’ On stage, with the Byrds, the Turtles, and the Gentrys, they were magical.

“What there was something that comes from jazz, and found its way into their stage show. That’s call and response. Neil and Stephen cutting each other. Someone would play a guitar line and the other would try and top the line. Stephen would play and Neil would then play a corresponding interlude of music. Whether it was actual lead or brilliant rhythm. And they traded lines. I don’t know if they sat down and worked it out or just did it in a competitive spirit. The audience was a dance audience. The front line was girls. They stood by the edge of the stage, then the dancers, the couples at the tables. Elmer Valentine knew. And he paid the band directly.”

Howard Kaylan (Turtles): I did see the Buffalo Springfield at the Whisky a Go Go. The band rehearsed in the house that Mark and I shared in Laurel Canyon on Lookout Mountain. Richie and Stephen slept on our floor. I moved out after a failed drug bust–didn’t know if the house was being watched. Paranoid. Richie moved into my room and the group practiced and wrote there. We all knew well before they played show #1 that they would be stars. The Atco deal guaranteed it. In the canyon, we were used to our friends becoming stars.”

Richie Furay: The best time for the band? As far as I’m concerned, it was right at the beginning when we were the house band at the Whisky (May-June 1966), with the five original guys–Steve and Neil, Bruce, Dewey and me—there was an undeniable magic. Whether or not we were the best musicians didn’t matter; we had magic, and we all knew it. We had replacements later on when Bruce had his immigration troubles–and Jimmy Messina was the only one who came close–but that original group was our best.”

In my 2008 MOJO ‘60s issue interview with John Densmore, drummer for the Doors, John provided some anecdotes on Buffalo Springfield circa 1966. “I shared a house with Robby [Krieger] [in 1966] on Lookout Mt. I had cruised Laurel Canyon many times previously over the years looking for a place because it was the coolest spot in Hollywood. We knew that Frank Zappa was there having jam sessions that we Robby and went too. That was interesting. He didn’t smoke or drink. He was wild enough to not need it. (laughs). He sort of wanted to produce us. Terry Melcher wanted to produce us.

“We were the house band at the Whisky a Go Go and everyone was trying to figure out what to do with ‘Light My Fire,’ because it was so long. Sony & Cher’s manager, Greene and Stone, who also managed the Buffalo Springfield suggested that when it was recorded as a single to ‘put half on one side and half on another.’ Although it wouldn’t pay off because you’d be in the instrumental and then it would be over and then you would have to turn it over. Stephen Stills and Neil Young also told us about them. Greene and Stone had the only limo on the Sunset Strip. They would chauffer everybody around and so they felt like they made it.”

“I remember when we were the house band at the Whisky and Buffalo Springfield was playing and they flipped on some strobe lights in the middle of their set and Neil stopped playing and put his for arms over his eyes, ‘Turn it off! Turn it off!’ ‘Cause that shit fucks up epileptics, you know. Maybe ‘Expecting to Fly’ is a little bit about that.”

Russ Regan: Lenny Warwonker and I saw Buffalo Springfield at the Whisky a Go Go. They were incredible. My office at Loma Records was right next to Lenny’s at Reprise. Dickie Davis talked to Lenny about the group coming to the label, but soon afterwards, Ahmet Ertegun beat us to the punch.”

Dickie Davis: [Charlie] Greene and [Brian] Stone come on the scene. I brought them. They’re hot on the charts with Sonny & Cher. I knew they could sell anything. Charlie was one of us, like it or not. Brian, not one of us but knew how to behave. I belonged, but not in the retail end.”

Brian Stone: We first met Buffalo through their erstwhile road manager at the time, Dickie Davis. And he came to us, we were a hot company.

Dickie said, ‘I have this act and they’re really great. And you gotta hear them.’ Dickie, by the way, was originally a full one-sixth member of the group. Not as a manager but publishing. They gave that to him ’cause he was the one running around and doing everything for them and trying to make deals. So he brought us up. I got blown away when we saw Buffalo Springfield at the Whisky. It was electric. Neil Young and Stephen Stills were two sensational players. How they sung and acted together, worked together. Played off each other. I loved the bass player, Bruce Palmer. A killer, killer bass player of all time.

“Neil was quiet and shy. He was this extraordinary and co-equal talent and writer and Neil had songs. He was such a genius; he was writing this advanced stuff. Because Jack Nitzsche was our friend, and used to hang out a lot, and come to our sessions, so that’s how he met Neil. He had first met him one night at our office.

“Nobody in the group wanted Neil to sing any leads on songs because they didn’t like his voice. It was brought up in the studio a lot and in our office. Stephen would say, ‘I want to sing that song.’ Originally, it was written down when we met and first signed them that the way it was that Richie Furay was the lead singer. Positions were being defined in this group. We had to juggle that a little. Neil would say, ‘I want to sing this song. I wrote it. It’s my song.’ And I remember, there were huge discussions about these things, early, first album, where Stephen would say, ‘He can’t sing worth a shit!’ And I remember saying, ‘Hey. If Bob fuckin’ Dylan can put out records and get on the radio, Neil Young can sing. God damn it! It’s Neil’s song.’ And we would end up with about half the songs on the album were Neil’s, and half were Stephen’s.

“And the songs they wrote were incredible. And they were such different writers. So extraordinary. Stephen would write ‘Sit Down I Think I Love You’ and Neil would write ‘Flying on the Ground Is Wrong.’ They were just so different.

“We called Ahmet and got them signed for a big advance. We gave them a lot of money. They suddenly got a bunch of money and we bought them stuff. We got Neil Young a Gretsch guitar. But I think we got that and a lot of equipment for Buffalo Springfield from Wallichs Music City in Hollywood. As managers we did things for our groups. We would get a lot of instruments from them. Some of them we would have to buy. And we started to get them work. We knew publicity. We knew how to get them in the newspapers, music magazines, radio station alignments.

“Buffalo Springfield played a lot of gigs. Club dates, high schools, all over Southern California. And, we had a booking connection with the William Morris Agency, going back to Sonny & Cher. To initially get William Morris to take Sonny & Cher, they weren’t thrilled with it, because they didn’t want to handle rock ’n’ roll. We took Buffalo Springfield into the studio and made decisions about tunes, and what songs we would try to do.”

“I had met Neil Young a few times, briefly, earlier,” recalled Daniel Bourgoise, former A&R man for United Artist Records and founder of Bug Music who now oversees the estate of his former managerial client, singer/songwriter, Del Shannon. “I had secured a deal with Charlie Greene and Brian Stone for my friend from Detroit, Stephen Monahan. It was 1966, and I managed and published Steve. Greene and Stone produced one album for Kapp Records on Monahan, with ‘Jack Nitzsche’ sounding arrangements by Don Peake. Wrecking Crew playing on all the tracks. A single ‘City of Windows’ charted briefly. The Springfield were also around the office a lot, and the lady who handled the publishing there put Monahan and Neil together to write. We went to the house where they all lived a few times, but nothing much ever came of it.

“In 1966, maybe early 1967, Del [Shannon] and I were waiting for the light to turn, so we could cross Sunset Blvd. and go to the Whisky a Go Go. Out of the corner of my eye, I spot someone running across Sunset diagonally, dodging traffic. It was Neil Young. He rushes up to Del, shakes his hand, telling him that he is a huge fan, and his favorite record was ‘Stranger in Town!’ Neil asked if Del still had the mink guitar strap that was in all the photos at the time. He said he LOVED that mink guitar strap!”

Buffalo Springfield then recorded their debut disc with managers/ producers Greene and Stone at Gold Star Studio in Hollywood, home of Phil Spector’s epic musical productions. Owners Stan Ross and Dave Gold with Larry Levine with their landmark studio made pivotal contributions to Buffalo Springfield’s studio endeavors. Ross trained Doc Siegel who engineered Buffalo Springfield with Tom May.

Ross and the Gold Star team previously recorded Eddie Cochran’s “Summertime Blues,” “20 Flight Rock,” and “C’mon Everybody.” Ritchie Valens’ “Come On, Let’s Go” and “La Bamba,” too. The studio was also the location for Don & Dewey’s “Jungle Hop,” Jewel Aikens’ “The Birds and The Bees,” Dobie Gray’s “The In Crowd,” Johnny Crawford’s “Cindy’s Birthday,” Chris Montez’s “Call Me,” and Thee Midniters’ “Land of 1000 Dances.”

In addition, Charles Wright & the Watts 103rd Street Rhythm Band waxed “Express Yourself” in the location and “Endless Sleep” by Jody Reynolds, was done at that facility. Sonny & Cher, Bob Lind, Iron Butterfly, Jackie DeShannon, Hugh Masekela, the Monkees, the Seeds, the Turtles and The Band all cut at Gold Star. Kit Lambert produced the Who’s “Call Me Lightning” at Gold Star and mixed their “I Can See For Miles” inside the building as well.

In a 2000 interview with me in Goldmine, Ross described the history of the Gold Star atmosphere.

Stan Ross: Gold Star used to be a dentist’s office. We started pulling teeth a different way. Gold Star was built in 1950 and lasted until 1983 at 6252 Santa Monica Blvd until a fire destroyed the property in 1984. Upon closing in 1984, the property became a mini-mall.

“Gold Star was built for the songwriters. They were fun, wonderful people to be around: Jimmy Van Heusen, Jimmy McHugh, Frank Loesser, Don Robertson, Sonny Burke. It gave it the wall of sound feel. Dave (Gold) built the equipment and echo chamber. We had so much fun with that echo chamber; it never sounded the same way twice. Gold Star brought a feeling, an emotional feeling. Gold Star was not a dead studio, but a live studio. The room was 30 X 40 feet.

“It was all tube microphones. We kept tubes on longer than anyone else. Because we understood that when a kick drum kicks into a tube it’s not going to distort. A tube can expand. The microphones with tubes were better than the ones without the tubes because if you don’t have a tube and you hit it heavy, suddenly it breaks up. But when you have a tube it’s warm and emotional. It gets bigger and it expands. It allows for impulse.

“I was always impressed by the songwriting abilities of the Buffalos, especially Neil Young.”

Richie Furay: Look, walking in to Gold Star studio. I’m a young kid from Ohio. And to go in that studio, with all the history, and hear our music coming through those speakers, even though it’s a four track, was bigger than life.

“Ahmet Ertegun also encouraged us to learn the board. So we’d go in and we would record ‘em like some of the vocals were going to be done. Ahmet had heart and soul for the band. ‘Make these demos. Do whatever you need to do to make the product.’ Because of him the band got launched a lot quicker then maybe it could have. He definitely saw something in this band right away.”

Rodney Bingenheimer : Greene and Stone were managers and producers, real show biz operators, who represented Iron Butterfly, the Poor, Bob Lind, the Cake, Dr. John, Jackie De Shannon, Sonny & Cher and Buffalo Springfield. I loved Gold Star. I played one of the tambourines on Sony & Cher’s session for ‘Bang Bang (My Baby Shot Me Down).’ At Gold Star everyone was wearing Levis and some buckskin things, Fairchild moccasins. Dewey Martin liked to wear velours.

“Charlie and Brian were always at Gold Star. I loved Buffalo Springfield. I always saw them at the Whisky a Go Go. It was a ‘jangly’ folk sound. Sort of ‘Byrdsy’ in a way. ‘Country Byrds.’ They would gig all over Hollywood: The Troubadour, Hullabaloo. Charlie and Brian were really good behind the board. I liked them as record producers. They were kind of mysterious and had a black Lincoln Continental limo. These were the days when managers did many things.

“Greene and Stone were on top of it and got their people into the best studios and on all the best tours. They knew how to hustle and were good on the telephone. They had Buffalo Springfield open for the Rolling Stones at the Hollywood Bowl in July 1966 even before they had a record out. I liked the first album. ‘Clancy’ was incredible. ‘Down To The Wire.’ Stan Ross was all over the place getting it together. Stan and Larry (Levine) were more than engineers. They knew what they were doing as if they were the producers. They didn’t manage bands or run record labels.

“Always lurking was Ahmet Ertegun at all the sessions I was at from Sonny & Cher through Iron Butterfly. He was like a Turkish monk sitting in the corner. A guy with a goatee. He always had suits on and came by limo. Some of the band would leave the studio and go back near the parking lot to smoke pot during a break when no one was looking. I think Ahmet went back there, too. Ahmet was around the Sonny & Cher sessions. It took me a couple of years to figure out he was the record company guy. Ahmet would never would intrude and everyone was always around him and patting him on the shoulder. Cher would sit on his lap. It took me a while to learn he had the checkbook. He grooved on the music. Ahmet did seem older than everybody. He was scouting talent. He wasn’t a snob and very approachable.”

Dickie Davis: (Road manager/co-publisher): I heard all the demos on the tunes for the debut album. It was the stage act. There was another thing. When you had songs you took them to the stage and worked them out. The arrangements were worked out by the band as performance numbers. So we got to Gold Star. Everything sounds good to us and we’re having the time of our lives. I’m there every night.

Henry Diltz (Photographer): I went to Gold Star in June 1966 when they were doing their debut album. I had recorded there before with the MFQ and Phil Spector. I was in the rom in July when Buffalo Springfield cut ‘Nowadays Clancy Can’t Even Sing.’ I met their dog Clancy in the parking lot.”

Dickie Davis: ‘Clancy’ blew my mind lyrically. I thought Neil was a poet who can write pop songs. So was Dylan and Paul Simon. I was a poet myself. It was like a country song that had just grown a little. And Neil did his own stuff like ‘Burned.’ But I liked ‘Go and Say Goodbye’ better. And nobody wanted Neil to sing. When I started hearing all his material I started to realize I might have it wrong. That I had seen a band, a group, and the focus. I wasn’t dedicated to Stephen Stills or Neil Young as major talents. I wanted the band to succeed as a band. And I put all of my energy into that.

“‘Clancy’ was poorly recorded. By the way, there were background vocals that never got put on because there was no room on the tracks. It was Ahmet’s choice for ‘Clancy’ as the single that August, The same day it was released Los Bravos releases ‘Black is Black’ and the Beatles ate up all the airtime available.”

Kirk Silsbee: (Journalist): The Springfield had three good writers, but Neil cranked out the bulk of the band’s material. It was very smart to give those vocals to Richie Furay. Neil had an odd voice, with a haunted edge to it and lacking warmth. Richie’s voice, on the other hand, was far more engaging and even sweet, in the best sense of the word. But listen to ‘Clancy’–it’s quite a poignant vocal performance. The lyrics on ‘Clancy’ are emotionally torturous, which seemed to be Neil’s stock and trade at that time.

James Cushing: (Deejay): What was powerful about that song was partially the voice of Stephen Stills and partly that minimalist guitar from Neil Young. From the first album, Neil Young’s quirky, anti-virtuoso concept was fully formed. You hit just the right notes and let them ring out. Neil also voices chords in a unique way I don’t have the technical vocabulary to describe, but there’s something about the way he voices a chord versus the way Stephen Stills voices a chord. Maybe he likes to use different intervals. Maybe he likes to hit the notes in a different way. Together they are collaborative and competitive. As far as their sense of rhythm goes, I think Neil’s sense of rhythm is much more rooted in folk strums and strings. Stills is actually more rhythmically interesting than Neil. But one of the reasons that Stills sounds so interesting is that Neil always gives him that support. Stills’ strengths are enhanced by Neil’s strengths.”

Jan Alan Henderson (Writer): My introduction to the Buffalo Springfield was not traditional in the 60s rock lexicon. My new neighbors on the west side of Laurel Canyon, Charlie and Marci Greene, had cars parked in their driveway which displayed a curious bumper sticker, which read: ‘Why can’t Clancy sing?’ I didn’t take much notice of it, but soon groups of long-haired people congregated on their driveway when their cars weren’t there. These people turned out to be Sonny and Cher, and the Buffalo Springfield. The straight-laced neighbors took absolute offense to this squatting, and threatened to call the police, and made my mother well aware of this. To which, like Lowell George, Richie Hayward, and the band the Factory, who were on the west side of me, I would inform the parties that somebody in the neighborhood had called The Man to eradicate them.

“I had been a fledgling drummer without a drum kit, but a couple of drums and cymbals stashed in my garage, which I would beat the hell out of for three or four hours a day. Charlie’s wife, Marci, recognizing what can only be described as my dubious musical adventures, had their chauffeur knock on my door one afternoon. I thought it was the fuzz and I was going to get busted. Here this lovely gentleman, in full chauffeur regalia, handed me a stack of LPs and singles a foot deep. Among the records in this collection was the Daily Flash’s ‘The French Girl,’ and the first release of the Buffalo Springfield album, without ‘For What It’s Worth’ with ‘Baby Don’t Scold Me.’ The hit single was supposed to be “Nowadays Clancy Can’t Even Sing,” which to me is more emotive of the times than ‘For What It’s Worth.’”

Rodney Bingenheimer: The first album didn’t really capture the Buffalo Springfield on stage. Just a little. I later did go to Columbia studios and saw the mix of ‘For What It’s Worth’ happening. Pretty amazing. In the second week of December of 1966 I went with Sonny & Cher in a Rolls Royce to the radio station radio KBLA-sponsored concert at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium for a show with Love, Turtles, Gene Clark, the Standells, Captain Beefheart & His Magic Band, the Seeds, Music Machine, the Count V, and Buffalo Springfield. It was like the first time ‘For What It’s Worth’ was done live. I knew it was going to be a big hit.”

Bruce Gary: Dave Diamond the KBLA deejay was one of the show announcers. Dave broke Love, the Doors and Buffalo Springfield in the L.A. radio market. As a sixteen-year-old I infiltrated backstage at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium and immediately stumbled over some equipment and electrical cords, pulling the power generators out of the wall sockets, which caused a fifteen-minute blackout delay at the show before the house lights went back on.”

Brian Stone: Their first album we had shipped 10,000 albums. And then Ahmet heard “For What It’s Worth,” and said, ‘this has to be on the album!’ And then by March it was inserted and “Baby Don’t Scold Me” was removed.”

I would buy both versions of the LP at The Frigate record shop in Los Angeles near Television City.

The Stills’ composition “For What It’s Worth” has emerged as an anthem of protest. A record reflecting the Sunset Blvd. disturbance between local law enforcement against the largely underage kids of Hollywood congregating at the intersection of Sunset and Crescent Heights, at the lip of entrance to Laurel Canyon. Writer Jan Henderson, deejay Art Laboe and I were present that evening on Sunset which informed the Stills’ tune.

Actually, the recording, besides a tip of the percussion hat by drummer Dewey Martin to “Get Out Of My Life,” courtesy of Lee Dorsey, was partially informed by Still’s fondness for another three-guitar, multiple songwriting team, Moby Grape.

Stan Ross became the unsung hero of their first real AM radio chart entry. “For What It’s Worth.” Ross employed strategic microphone placements and the implementation of a hand mallet and restricted drummer Dewey Martin from utilizing his foot pedal or kick drum on the early tracks.

Stan Ross: It was a sound that I had worked on at Gold Star. They called me late at night to go up to Columbia studio and help fix the song. I was in Gold Star with engineer Tom May working with Sonny Bono on a song, ‘Sunset Symphony.’ Charlie Greene and Brian Stone called and said Buffalo Springfield had wanted to cut that night too, but the studio wasn’t available. I then received a call at 11:30 that night. ‘We’re in trouble. We’re sitting here and nothing is happening.’ Tom May and I went over to Columbia. The kids were on the floor, and having a good time. I have two hours and I have to get some sleep for a session tomorrow morning.

“I heard the song and had a great idea for the drum rhythm. I thought the drummer shouldn’t use his foot, and wanted someone to use a hand mallet. We have eight tracks here, and I want to be able to put the kick drum on track boom ‘Boom boom. Boom boom.’ And I wanted to take the guitar and wrap some paper around the frets and I wanted a back beat. Not using the drum but using the backbeat of the frets of the guitar. That’s a sound and technique I worked on at Gold Star many years ago. A very crispy wonderful sound. So we put together the rhythm sound, basically.

“I left at 2:00 A.M. after telling them ‘all you got to do is put the vocals here and put some guitar fills in.’ We didn’t have 8-track when Buffalo Springfield came in, that’s why they went to Columbia ‘cause they had a 8 track machine.

“After we got the track sounding like a track at 2:00 a.m. I said, ‘look guys, all you got to do is get the vocals around here and put some fills in between the vocals.’

“The next morning I got a phone call from (Atlantic Records) Ahmet Ertegun. ‘I got the record. The guy did a job in the studio, and I want you and Phil Spector to listen to two mixes. And I want you and Phil to tell me which mix you like.’ So Phil came down to Gold Star. CBS sent over mix one and mix two. And Phil and I listened, looked at each other and agreed, and that’s the record that came out.”

Spector would be subsequently thanked on the back cover of Buffalo Springfield Again.

Dickie Davis: So Stephen comes down with a song which is vaguely reminiscent of a Moby Grape song. It was very close. This was not a song that had been taken to the stage. I remember, maybe after Gold Star, going to Columbia. They laid down the tracks. Stephen sang the vocals and there were some background vocals worked out.

“Neil’s contribution of the harmonics were done by plugging straight into the board in the studio. The clarity of those notes have to do with there’s not an amplifier and a microphone involved. It wasn’t almost a technical decision. It was kind of like, ‘Neil’s gonna sit in the booth and do this,’ you know. It might have been that simple.

“I loved the playback. It was a well recorded tune. Now, it wasn’t a Beatles-style dance tune. Which was what we thought we had to do to be successful. It was a protest song, and Stephen, the minute that song was a success, he started complaining, ‘Everybody is gonna think we’re a two-bit protest band!’ And I would say things to him like, ‘Stephen, you wrote the song,’ you know. ‘It’s a success. It’s a hit!’

“You gotta see that Greene and Stone’s contribution was strong. Their ability to have hits on topical subjects was known. And proven by Sonny & Cher. ‘Laugh at Me,’ an incident that Sonny wrote about when he and Cher were asked to leave Martoni’s restaurant because of their clothes. And so Ahmet Ertegun could understand when Brian or Charlie touts ‘For What It’s Worth,’ ‘We got this.’

“In Los Angeles, Buffalo Springfield had a decent following. The relationships with radio station KHJ with program director and Ron Jacobs and B. Mitchel Reed and then Dave Diamond on KFWB helped, and the KHJ deejay the Real Don Steele supported Buffalo. ‘Clancy’ and ‘For What It’s Worth’ received plenty of airplay on KHJ, a Drake-Chenault chain Boss Radio format. Nobody didn’t like the band.”

Kirk Silsbee: Aside from ‘For What It’s Worth,’ it wasn’t a hit-record band. There was no FM in late ’66, but the Springfield eventually got a lot of FM airplay. In the year-and-a-half up to June 1967–when the format changed–there was no station like KBLA. It was our pirate radio, and it set the stage for the FM revolution to come.

“Beginning in last part of 1965, KBLA made the bold choice to acknowledge the albums coming from these L.A. bands–not just the one or two hit songs pressed as 45s. And even though they weren’t getting played elsewhere, Burbank’s KBLA gave them parity with hit records. That was revolutionary as far as I was concerned. ‘Flying On The Ground is Wrong’ is one of the best post-Dylan songs of its time. In just three stanzas Neil brilliantly paints a picture of emotional disconnection and missed opportunity. Even though there’s an inviting girl in front of him, nothing is quite right in his world. It’s very poignant and you can’t minimize Richie Furay’s contribution to the success of the recording.

“I don’t know who arranged ‘For What It’s Worth’ but the pacing was brilliant. I think Dewey Martin has a great role on that particular record, and Bruce is also playing pretty minimal stuff. Of course, we know they could both play far more. It’s just a stark well-paced lament. Think about it this way: this is a hit record that went top ten. That’s pretty remarkable in itself. It was a hit record that had a very long shelf life and is still being played, discussed and sampled many years later. But in the middle of Hit Record Land, where everything had to be moving and they wanted bright colors and bright sounds in the music, this is a dead slow serious lament. It’s contrary to everything around it.”

Chris Darrow: I saw the Springfield live at the Hullabaloo in Hollywood on a bill with the Seeds, the Standells and the Yellow Pages. This was in on February 2, 1967, right after the release of their first album, Buffalo Springfield. Their first single ‘For What It’s Worth,’ was a hit and they were on their way. Their style on stage was tight and clean and was a mixture of both folk rock and country rock.”

In the April-May 2007 issue of Record Collector News magazine, writer Ralph Hulett described Buffalo Springfield on March 24, 1967.

“I saw the Springfield with a number of other bands at the Kaleidoscope, although when I first paid my $6 and went in I didn’t even know who was on the bill. It was a benefit for underground FM stations Pasadena’s KPPC and San Francisco’s KMPX. My Sunset Strip musician friend Clyde Johnson and I saw about six bands and then decided to leave after Steppenwolf and Clear Light because it was getting close to 10:00 p.m., it was a school night, and we didn’t want to get killed by our parents. But then the announcer came out and said the Springfield was coming out. We looked at each other and I said, ‘Well, we can’t leave now. We’ll leave for sure after this!’ Clyde agreed—but then the Jefferson Airplane came on after the Springfield, and we changed our minds again. Hollywood nightclubs could be unpredictable and influence teenage minds big time.

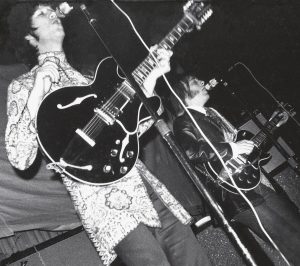

“As far as seeing the Springfield went—well, what a high-powered, fun, fantastic show. The group went crazy on ‘Mr. Soul,’ playing the guitar breaks at twice the speed. There were the well-known ones like the teen anthem, ‘For What it’s Worth’ and ‘Nowadays Clancy Can’t Even Sing.’ Stills then tore up the place during ‘Rock and Roll Woman’ as he slid across the sawdust-strewn stage during the guitar break in his moccasin feet, playing away. But the real excitement came near the end when Stills and Young did a guitar jam during ‘Bluebird.’ Young, like an Indian scout in his swaying fringed buckskin coat, blazed new musical ground as he traded licks with Stills. Clyde and I watched spellbound from about 10 feet away. The spontaneous, electric intensity soared over us all, and the entire song lasted for around 10-15 minutes. This was a show I’d never forget.”

Rick Rosas: Mark Guerrero and I saw them live at Cal State L.A. It was good but I was hoping it could be a little bit better. They were a recording band to me. Back in those days I don’t think they had guitar tuners or really good sound systems. P.A.’s were pretty bad back then. We were still knocked out by them. I remember going backstage and seeing a white Econoline van with the name Buffalo Springfield printed on the door. Wow!

“Buffalo Springfield had a big impact on me. From their first record they just caught my ear. I just loved the guitar playing and the singing. It was like the California Beatles. They were just so good. I heard ‘For What It’s Worth’ the first time driving around in East L.A. We’d end up in Hollywood every once in a while cruising the Sunset Strip, past Pandora’s Box, where Stephen wrote about it. I think at the beginning of Buffalo Springfield, Stephen Stills stuck out the most. His voice was recognizable. And then as it went on Neil’s voice slowly slipped in. He didn’t sing much on the first album. And when he did sing he was so unique. It wasn’t perfect but it was great. And Ritchie.

“When Mark and I noticed that their first album was recorded at Gold Star, we needed to record there as well. We were kids. I could not believe we were at Gold Star. It made a big impact on me. We [Nineteen Eighty Four] did a four hour session on September 30, 1968 recording two of Mark’s songs. [“Baba” and “Amber Waves].”

Buffalo Springfield’s world splintered in January 1967. Bassist Bruce Palmer got into some immigration problems and deported back to Canada. During the period the band utilized various fill-in bass players (Ken Kolbun, Jim Fielder, and Bobby West on session dates)-from January to May-was when they were ostensibly recording their second album. The working title was Stampede.

Rodney Bingenheimer: In 1967 I remember going up to Lewin Record Paradise on Hollywood Boulevard and got a couple of copies of the album slicks for what was supposed to be a Buffalo Springfield album called Stampede. They didn’t use that cover for Buffalo Springfield Again.”

They remained at Gold Star until late May when Bruce returned. Then Neil quit in early June, coming back to the outfit in August.

In 2014 I asked Peter Lewis about the creative and combative Stills and Young musical friendship he observed.

“Stephen Stills and Dewey Martin had a beach house in Malibu in 1967. Moby Grape had one in Malibu at the same time. We were renting Rod Steiger’s beach house. One day I remember Neil and Stephen walked in and they wanted to borrow this boat that Rod Steiger had. It was a dingy. This encapsulates their whole relationship. They wanted to grab this boat and go out and get it beyond the shore break. They both climb in there and then they spent a half an hour on who is going to get to row. And then here comes this wave and sinks the whole thing, you know. I don’t remember if the boat ever got recovered. Nobody from the band went out and got it.

“But today Neil Young is rowing the boat.”

Brian Stone: The problem with Buffalo was that clash between Stephen and Neil. Having these two dynamic, talented, incredible, mighty playing forces like this, Ahmet used to say to me all the time, we had hit records with him at Atlantic with Sonny & Cher, ‘I Got You Babe.’ Ahmet would say ‘that next to the Beatles, Buffalo Springfield were the best American rock group ever of all time.’ It was very rare to have two — if you want to include Richie Furay as well, three — extraordinary singers, players in the same group.”

Buffalo Springfield then started doing their sessions to Sunset Sound and discovered engineers Bruce Botnick and Jim Messina. It would become their

studio of choice for Buffalo Springfield Again plus tracks for their next album, Last Time Around.

Rodney Bingenheimer: In late April of 1967 I saw the amazing KHJ radio station appreciation concert at the Hollywood Bowl with Buffalo Springfield, the Fifth Dimension, Johnny Rivers, the Seeds, Brenda Holloway and the Supremes. Buffalo Springfield did an early set and then took a plane to San Francisco to play the Fillmore Auditorium.”

Kenneth Kubernik (Author): 93 cents is what I paid, sponsored by ‘93 KHJ,’ to see that ‘totally groovy’ show at the Hollywood Bowl. I was twelve years old, a veteran music consumer, fitfully replacing my picture-sleeved singles with the mighty LP. I was primed for something ‘heavy’ that would ‘blow my mind’ (not that I had a clue about the lurid underpinnings of these game-changing expressions).

“I had seen the Springfield several months earlier at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium (home of The TAMI Show) at a concert sponsored by radio station KBLA – Los Angeles a town ping-ponging between fickle loyalties to a raft of AM stations and their delirious radio personalities.

“I loved that Neil and Stephen played those ornate Gretsch guitars, as gold-plated and stylish as a Louis Quatorze furnishing. I remember them as being both rowdy and detailed in their music and their deportment; those fringe jackets nailing that curated pose of lawlessness.

“There was nothing transgressive about them – they were no threat to the state like the Doors or Arthur Lee and Love. They strived for a more authentically American sound; if they had a great keyboardist on board something of The Band lurked around their edges. Even then, though, you could sense that they weren’t built to last – a half-dozen great songs and… kablooey! But that’s always been Neil and Stephen’s MO.”

Andrew Loog Oldham (Record producer, manager, author): When the Rolling Stones were at The Hollywood Bowl in summer of 1966, Buffalo Springfield was on the bill. I got this weird, sort of ‘Kubrick-type memory,’ of going when the Stones are in Hollywood.

“You gotta remember, you have Greene and Stone, Leiber and Stoller and you got Andrew Oldham. You need to remember I had a partner, Tony Calder, who was an amazing contribution to my life. Charlie looked like he should have been in the Young Rascals at that stage. Charlie was an energy guy, always on the phone. Brian was laid-back. Brian Stone was Brian De Palma watching it all.

“One of the great things about Greene and Stone is that they managed to straddle the next wave. It’s quite an achievement to go from Sonny & Cher to Buffalo Springfield. That had to be war from the beginning. To go from Sonny & Cher, Buffalo Springfield to Iron Butterfly is a leap that I almost made with some of the Immediate Records acts. Particularly one of them, the Nice. But it wasn’t something I ever embraced. They went all the way. Which is a great achievement. Not many people manage to guide the next era.

“All due credit to Buffalo Springfield and Greene and Stone and whomever they were associated with. The hoodwinking of that band over America was that Americans were so desperate to take back the crown that we British had taken away from America that they overlooked the fact that Buffalo Springfield and the Doors were basically sloppy versions of the Beatles. I mean, camouflage is what sells things. Of course now we can look at the actual ingredients that went into the soup. And these people are so infatuated with the Beatles. I don’t think I noticed that Neil Young’s ‘Mr. Soul’ nicks from ‘Satisfaction.’ I don’t think I cared. I didn’t pay any attention to Otis Redding doing his version of ‘Satisfaction,’ either.

“In spring 1967 Neil Young left Buffalo Springfield. I was in West Hollywood during May and June working on the Monterey International Pop Festival. I had an encounter with Stephen Stills out on the steps of the Monterey production office that was in the old Renaissance club. Stills was speaking about whether I’d be interested in talking about management. There are some things you just don’t do, you know. 1967. Not a good year for me.”

Dickie Davis: After the first album was released the group really held Greene and Stone responsible for the down time and the failure of the first time. So, the group wanted Greene and Stone gone. And I negotiated that with a lawyer Ahmet provided.

“Ahmet had stepped in before – to referee between Stephen and Neil at recording sessions. Both of them trusted, admired and respected him. And Ahmet continued working with Greene and Stone. They brought him the Iron Butterfly.”

Rodney Bingenheimer: I attended the June ’67 Monterey International Pop Festival. When Buffalo Springfield came on stage I was the first person to yell out, ‘Where’s Neil?’ I didn’t know Neil had split from the band.”

Dickie Davis: After Neil quit, Doug Hastings of the Daily Flash would play guitar on shows. Then one evening Stephen said, ‘Neil’s comin’ back tonight.’ So if you wonder if it was Stephen’s band or not, it was Stephen’s band.

Jim Roup: I saw Buffalo Springfield during their June 30th-July 1st 1967 booking at The Hullabaloo. David Crosby guested on guitar. Michael Clarke of the Byrds and Buddy Miles did a drum jam at the end of one show with Dewey Martin. Even though Neil wasn’t on stage, most of the audience didn’t make a big deal about it. I did hear Neil sat in over the weekend at one show for a couple of songs.”

In 2001 I interviewed Richie Furay about Buffalo Springfield. Sections of our conversation first appeared in Goldmine and in my 2017 book, 1967 A Complete Rock Music History of the Summer of Love.

“We were always comfortable singing someone else’s song early on. The first album and some of the second, you can hear the cohesiveness was a group effort, there was not the possessiveness of ‘this is my song, this is my baby, I’m singing it because I wrote it.’ Early on there was this ‘what does this sound like with you singing?’ I know we tried ‘Mr. Soul’ with everybody singing and it sounded best with Neil. “The individual members brought their own take on what was being presented to the song. We liked the Beatles with John and Paul singing harmony. Stephen and I did a lot of that unison singing. That we picked up from the Beatles but then there was a lot of experimentation”

The group spent the first half of 1967 making Buffalo Springfield Again, which was the first album to feature songs written by Furay (“A Child’s Claim To Fame.”) Stills and Young both contributed some classics with “Bluebird” and “Rock And Roll Woman” from Stills, and “Mr. Soul” and Young’s “Expecting to Fly.”

In 2014, I interviewed record producer and manager, Denny Bruce. Portions later were published in Neil Young: Heart of Gold.

Denny Bruce: In 1966 I first met Neil when he was living in an apartment at the Commodore Gardens in Hollywood. I saw Buffalo Springfield play all the local clubs. The Whisky, Gazzarri’s and smaller places. After performing Neil would go to his apartment still wide awake and write songs. Neil and I had a casual friendship and he was a true fan of music. Neil was always interested in my opinion about all matters of things pop.

“Jack Nitzsche liked to hang out at the Greene and Stone offices on Sunset which were always open-all night just to see if anybody was really going to show up. There was a pool table. One night I was talking to Neil because he basically is a shy person, I introduced Neil to Jack. Neil indicated to us that he wanted to create a musical and lyrical mix of the Rolling Stones and Dylan. In 1966 Jack took me to one of the Stones’ Aftermath sessions at RCA he was working on where Andrew Loog Oldham was producing.

“In 1967, Neil and the band left Gold Star to do Buffalo Springfield Again. And Neil finally saying, ‘I’m gonna use some other players.’

“Before the album began I went up to Neil’s cabin in Laurel Canyon. He had his jumbo acoustic 12-string guitar and he’s halfway through a song that turned out to be ‘Expecting to Fly.’ There was always a different tuning and Neil was also really good at using various time changes. Like in ‘Clancy,’ which is 3/4 time.

“Then Neil starts talking about ‘Expecting to Fly’ and said, ‘I hear it as a song for the Everly Brothers.’ I agreed and responded, ‘Yeah. I can hear their voices on it.’ And I added, ‘Jack Nitzsche is in Las Vegas. He just had a recent visit to Mo Ostin at Reprise Records, and was looking for a gig.’ And Mo said, ‘What could you do to maybe help the Everly Brothers with their song selection and production?’ And Jack answered ‘If they just had the right material, that’s the name of the game.’ I told Jack, in my opinion, ‘Expecting to Fly’ is perfect for them. And he goes, ‘That will be the first thing I listen to when I get back to L.A.’ Jack and I went over to Neil’s and heard the song and both of us knew it was great. The Jack said, ‘Fuck the Everlys. This is for Neil Young. We can make a great record.’

“I did attend one of the marathon session dates for ‘Expecting to Fly.’ Jim Gordon on drums and Don Randi on keyboards. All good players who Jack picked. He said to Neil, ‘This is gonna be a good solo deal. Not a Buffalo Springfield record.’ And Neil said, ‘Good. I don’t see them on this record.’ I said, ‘Not even Dewey?’ And Neil shrieked ‘No!’ Jack really believed in Neil’s music. And Jack knew Neil would eventually become a solo star. He knew he wasn’t meant to be in a band.”

“I had met Don Randi a long time ago,” arranger/producer/songwriter, Jack Nitzsche reminisced to me in a 1988 interview published in Goldmine. “He was a pianist at a jazz club on La Cienega. He was cool. He looked like a beatnik. His hair was right. He had the attitude. He didn’t smile when he played.

“I met the Stones in 1964. Andrew Loog Oldham called me up. He and the group had just met Phil Spector in England and wanted to meet me. Sonny Bono, who was working for Phil drove them to the studio. Brian Jones was in a three-piece suit and tie. The saw me work with Edna and Merry Clayton at RCA. A little later, the Stones started working at RCA and it had a big impact on me. A whole new way of approaching records. I was used to a three-hour record date, and they were block-booking twenty-four hours a day for two weeks, and doing what they wanted.

“When I did film scores and started to bring in exotic instruments, I wanted to make the sound different and wanted room to experiment.”

Don Randi: (Keyboardist) Jack Nitzsche called me to play keyboard on some dates in 1967 at Sunset Sound. When I walked into the studio I didn’t realize it was for Buffalo Springfield. I thought it was for a Neil Young album, ’cause that is what he was supposed to be breaking away from and going on his own. Hal Blaine and Jim Horn are on the track. I played piano and organ.

“When Jack and Neil asked me to play on the end part of ‘Broken Arrow’ they were both waving me on to keep playing. I kept lookin’ up at them, ‘Are you ever gonna tell me to stop?’

“Jack really enjoyed working with Neil. This goes as well to ‘Expecting to Fly.’ Russ Titelman, Carol Kaye and Jim Gordon are on it. I had some little head chart arrangement to work from and another of the tunes might have been sketched. It was pretty wide open with the chord changes. And all you had to do was hear Neil sing it down with an acoustic guitar and you sat there, ‘Oh my goodness.’

“He was so talented. And Jack enjoyed Neil and to be with him because Neil was so talented. Jack and Neil were a team and had a mutual admiration society. And they liked each other, and recording with them was easy. Neil wrote cinematically and Jack arranged his own records cinematically. He did movie scores with me as early as 1965. Jack and I never judged artists by their voices. To me it didn’t matter ’cause I loved the music so much. And Neil was able to sell it. There are some people you can’t stand them on record until you see them live. And once you see them live you can understand their records. That doesn’t happen a lot. But it does happen.

“And I would love to have said how big Neil was gonna get. I don’t think he realized it. But I loved Neil’s music. Goodness gracious. This guy’s writing… I thought everybody and their mother was gonna try and start doing his songs. I knew he was a songwriter. Some of the tunes were movies. They were scripts. To me, Neil was like another Dylan. That’s what he reminded me of. He could do Dylan but I think he did Dylan his way. It was Neil Young. It wasn’t Bob Dylan. You have to realize that as great as a musician and as great as a songwriter he is, Neil would also realize talent himself. He realized a sound that he liked from a guitar. Neil knew that the only way to get it was to have that guitar. You’re not gonna get that off a Tele. You’re not gonna get it off something else.

“Neil was smart enough, and most of the good writers and players, if they didn’t have the acoustic guitar they went to that kind of guitar. Neil liked to experiment. And he would say, ‘Oh my goodness. Why don’t I do that?’ And he had the wherewithal and had the time. He had the time to take his time. ‘Wow. That’s a real nice sound. I like this. I don’t like that.’ Neil was smart enough to know what he wanted and knew how to get it. And Neil had Ahmet Ertegun in his corner.

“Ahmet encouraged the guys in Buffalo Springfield to write and do demos at Gold Star. I lived at Gold Star throughout the entire sixties. Ahmet and Nesuhi were two of the smartest people in the record business. They almost signed me to Atlantic.”

In 2012 I spoke with engineer/producer Bruce Botnick for my book Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll in Los Angeles 1956-1972 who worked with Buffalo Springfield at Sunset Sound studios.

Bruce Botnick: Sunset Sound was built by a man named Alan Emig, who had come from Columbia Records, and was a well-known mixer there. Tooti Camarata, a trumpet player originally and an arranger, and did big band stuff in the 1940s and ‘50s had a friendship with Disney and decided to build a recording studio to handle the Disney records and all the movies.

“The room was very unique. Tooti did something that nobody had done in this country. He built an isolation booth for the vocals. Sunset Sound had the amazing echo chamber that Alan Emig designed. Still phenomenal and having survived a fire. It still sounds incredible. With the strings being in the large isolation booth the drums didn’t suffer so we were able to make tighter and punchier rhythm tracks than any of the other studios in town were able to do.

“Just the natural great sound of the Sunset Sound room, and the echo chamber with the two consoles. Remember, in those days all the studios built their own consoles that were all tube. At one point Alan had worked with Bill Putnam, who had helped design the two pre amps in all the Universal Audio consoles. So when he came to Sunset Sound and he took it a step further and built this custom board with some of that circuitry and the two pre amps. So it really sounded great.

“On Buffalo Springfield Again, the songs were so strong, and so were the performances. We had somewhat two lead guitar players, between Stills and Young, two massive prolific writers between the two of them, and there was constant tension between the two- creative tension that would manifest itself in either one of them, you know, losing it for a few minutes. And then they would get back together and hug like crazy and do the songs. Again, it was about performance. We’d be recording a song, and Stephen would say to Neil, ‘Hey, man, I just got a new idea for a song.’ Or, ‘It isn’t finished but what do you think?’ And Neil would say, ‘Hey that’s great. Did you think about doing that there?’ So this went on constantly.

“Jack Nitzsche was being a part of this. He’s the one who brought them to me. I was there for ‘Expecting to Fly’ and then wound up doing ‘Blue Bird’ and three or four others. Maybe ‘Rock and Roll Woman.’ ‘Expecting to Fly’ was a real Jack extravaganza. And if you listen to it today… I wonder how Neil would have done it without that arrangement.”

Dickie Davis: I was there for Neil’s ‘Broken Arrow.’ We did some soundtrack research Neil wanted. I remember pouring through stock sound effect soundtracks with Neil, not even knowing exactly why I was going through them. I mean, he had something in mind. And we just did it. Like the heart beat sound we found.”

Rodney Bingenheimer: In ’67 I attended one of the recording sessions for ‘Expecting to Fly’ that Neil was doing with Jack Nitzsche at the Columbia studio, a union shop, where breaks were required every three hours. It was an old radio studio that was built in 1938 and comedians like Jack Benny, Red Skelton, George Burns and Gracie Allen used to do their radio shows.

“In the mid-sixties the rock acts on Columbia were in the studio. Like the Byrds, Paul Revere & the Raiders, later Chad & Jeremy, the Beach Boys when they did the 20/20 album and some of Brian Wilson’s SMiLE sessions. I shared a microphone with Paul McCartney on a vocal session for ‘Vegetables’ and was at the ‘Cabin Essence’ session.”

Brian Stone: Charlie and I went to New York with Buffalo Springfield. We used the Atlantic recording studios. Dewey Martin brought Otis Redding to a session. And Otis heard us recording Neil’s ‘Mr. Soul.’ And Otis said to us, maybe a week before he died, ‘I love that song, man, I’m gonna record it when I come back.’ And I said, ‘Huh?’ ‘Don’t you get it, man? ‘Mr. Soul!’ I’m gonna cut it.’ I remember it distinctly. I heard Neil didn’t want it done by Otis.”

Richie Furay: Otis Redding? Yeah—Dewey brought him to us. We were playing this little club in New York City, called Ondine’s (December 31, ’66-January 9, ’67), and Otis came in; Dewey knew him from somewhere. He sang with us–what a thrill that was! That meant so much to Steve. That’s right—Otis wanted to record ‘Mr. Soul.’ I guess Neil didn’t want him to. A visionary? Otis sure was; what a man!”

Henry Diltz: For their Buffalo Springfield Again back cover, Stephen called me one day and said, ‘Hey. I’d like you to write out this list of names that inspired us in your calligraphy handwriting. People we want to thank.’ I’m in there as Tad Diltz, my old name.”

Kirk Silsbee: The album has an Eve Babitz collage on the front cover and Diltz’s lettering on the back cover. I like the fact that the art director at Atlantic had the sense to step back and put his hands up. ‘No. This is a west coast product. It’s not going to look like every other Atco album with the second-hand Milton Glasser illustrations. No. we’re gonna do something different.’”

November saw the release of their second album, Buffalo Springfield Again, a defining moment in L.A. music history; like Brian Wilson before them, the Springfield meshed song craft with new recording techniques, elevating the music to a rarefied state of eloquence. I purchased the album at Wallichs Music City in Hollywood.

Heather Harris: I saw Buffalo Springfield with the Grateful Dead and Blue Cheer at the Shrine Exposition Hall in downtown Los Angeles on November 10, 1967 at a Pinnacle dance concert.

“To most everyone alive, classic rock bands like Buffalo Springfield are merely names, streaming purchases, bootlegs, rock and roll trivial pursuit answers for learned aficionados or even occasionally actual personal obsessions.

“To a teen contemporary to Buffalo Springfield’s performing history, they were the best of the batch of everything else around that one could take in. When asked how it is that I have photographs of live gigs by Buffalo Springfield (or Moby Grape, the Doors or the original Iggy and the Stooges) I answer A) I didn’t let not having optimum good equipment stop me (these earliest were taken with crummy Instamatic cameras); and B) access-wise, that all the greats began as local bands, and one has to train good intuitive radar to know which ones will remain “lifers,” people important in music for their entire careers. I did, despite an initial underage problem of not being allowed into clubs in the 1960s.

“And why the Springfield? Each member had a different onstage look and personality. Non-cookie-cutter distinctions have been important lessons for most of the best of the best, from the Rolling Stones to Guns N’Roses and beyond.

“In the mid ’60s’ era of a star or two with their friends as fellow learner/journeymen, bands live rarely sounded as good as their records did (often filled out with session people in the studio,) much less better than same live. With Buffalo Springfield, each band member evinced total rockin’ proficiency, making the band fire on all cylinders live, and every gig an explosive celebration of even more excitement. Like Moby Grape or the original Jeff Beck Group, they blew anyone else on the show totally away no matter what the billing, as practically goes without saying…”

Daniel Weizmann (Author): Sweet, lilting, and hypnotic, ‘Rock and Roll Woman’ by Stephen Stills was based on a jam session he had with Byrd-man David Crosby. Rumor has it that it’s an ode to Jefferson Airplane’s Grace Slick. True or not, the character he portrays was ultra-fresh in ’67–a free-spirited woman that is not a fan or a muse. She herself has total rock and roll agency.

“For my money, ‘Mr. Soul’ is about Dylan–whether or not Neil Young intended it that way. Young wrote it in five minutes at the UCLA Medical Center where he was recovering from a bad epilepsy episode. The dark clown / icon on a bad trip death wish, lost in the hall of mirrors that is fame channels the Man Behind the Shades, and delivers a tragic flipside to the bright comedy of the Byrds’ ‘So You Wanna Be a Rock and Roll Star.’ All over the “Satisfaction” riff turned inside-out no less.

“But both ‘Rock and Roll Woman’ and ‘Mr. Soul’ illustrate how Buffalo Springfield rep a new self-conscious sophistication, a kind of ‘meta-rock’ energy never before seen.

“Earlier L.A. bands like the Byrds, Love, and the Standells exposed their secret innocence with every move–even when they were mugging blue-steel looks for the camera, Stones-style. Some of those bands contained members that looked like they’d wandered in straight from the local soda fountain. Even the Doors seem like a happy accident of youth at times, pink-cheeked college kids jamming jazz on summer break.

“Buffalo Springfield on the other hand came out of the box seasoned, almost a pre-super group. Many members had been around the block, had flopped out at Monkees auditions and paid bar band dues. They enlisted Sonny & Cher’s management team and could pull off a full-force live show. Who else could play a complex jam like “Bluebird”–a pop-soul-folk blowout with acid rock frenzy, Gabor Szabo-style meanderings, and dense harmonies, all cascading into an Appalachian banjo denouement? They were almost like the last soldiers standing on the Sunset Strip, and their composure was ahead of its time, the birth of rustic rock royalty.”

Mark Guerrero: “Blue Bird”- a great rocker with folk overtones that features a fantastic vocal and acoustic guitar solo by Stills and rocking electric guitar solos by Neil and Stephen. When played live they would extend the song with longer solos and rock the house. ‘Hung Upside Down’- a great song about being down and confused that features Richie Furay singing the slow verses with his incredibly smooth and clean voice and Stills coming in on the choruses at his rocking best. Here were two of the best singers going in rock in their primes singing lead on the same track.

“‘Rock and Roll Woman’ shows Stills at his best as a singer and songwriter. It features a repeating acoustic double stop guitar lick that’s joined by a three-part vocal harmony doing the same figure that becomes the background to Stills’ edgy lead vocal. It’s a one of a kind song that also has great instrumental sections that typify the Buffalo Springfield’s unique style.

“I saw a riveting live performance of ‘Rock and Roll Woman’ at Cal State Los Angeles in 1967. It was a show stopper. During this period, I had a band called The Men from S.O.U.N.D who was very popular in East Los Angeles. We regularly played ‘Mr. Soul,’ ‘Rock and Roll Woman,’ ‘Hung Upside Down,’ and ‘Bluebird,’ which we would extend to 20 minutes or a half an hour at times. We absolutely loved doing these songs.”

Kirk Silsbee: There was nothing like ‘Expecting to Fly’ at the time, even within the Beatles’ canon. It’s rubato, without a set tempo. We hadn’t heard anything like this in a pop context. Neil had an odd voice, and though we’d heard him sing, this tune brought out a ghostly side of him with that floating/spacey arrangement. He’s floating in the piece, just as the strings are and the music is. It’s other worldly.”

James Cushing: ‘Broken Arrow’ and ‘Expecting to Fly’ join hands with the Beatles’ ‘A Day in the Life’ and ‘I Am The Walrus,’ Brian Wilson’s ‘Good Vibrations’ and ‘Heroes and Villains,” and Frank Zappa’s ‘Brown Shoes Don’t Make It’ as the most audacious experiments in the pop of the period. We hear in these songs that thing that makes any period in any art exciting: the sense of a single artistic mind made up of several people. Young, Wilson, Lennon, and Zappa seem to form a single mind in the moment of transcending previously accepted limits in a natural and organic way. Again, using the Beatles as an example, there is nothing from the Cavern in Liverpool or the Star Club in Germany that prepares one for ‘A Day in the Life.’ It’s a sudden leap. And there is nothing on the first Buffalo Springfield LP that prepares one for the blend of orchestral music, hard rock, live studio clarinet jazz. Yet, what we see here, with the Beatles, and Brian Wilson, is the sudden understanding that all of one‘s musical experiences are legitimate as material.”

Kirk Silsbee: ‘Broken Arrow’ was Neil’s SMiLE. The self-referential obsession found in ‘Broken Arrow’ wasn’t something we were used to hearing from these musicians–not just the Springfield but all of the musicians in the genre who were laying themselves open to examination. Dylan talked about other people and he crawled up their asses with microscopes. But he didn’t talk about himself. Then Neil Young laid himself open, rolled up his sleeves, showed his tracks marks the way Miles Davis did on ‘It Never Entered My Mind.’ Neil wasn’t afraid to show himself as vulnerable, or scared on Jack Nitzsche’s sonic highway. But the orchestration has Nitzsche responding to the words and the spare chords that Neil gave him.”

John Densmore: When I lived in Laurel Canyon on Utica, 1967, Neil Young was my next door neighbor. The landlord was Keiki. She had this rambling ‘Hobbit’ like place with two or three guest houses and Neil was in one and I was in the other. I have fond memories. I can remember when Neil said, ‘come on over. I want to play you something.’ And he plays me ‘Expecting to Fly’ and says, ‘I bought a house in Topanga.’ He had just quit the Buffalo Springfield and was moving out. And he said, ‘Well, I got forty grand, that’s what I got out of the Buffalo Springfield and bought this house. I’m out of here!’ Topanga is sort of the western extension of Laurel Canyon.”

In late October 1967 Forever Changes is delivered by Love, produced by Bruce Botnick, who was slated to helm the album with Neil Young, -who bailed for another hitch with Buffalo Springfield. Allegedly a Young arrangement or vocal and guitar contribution can be found on “The Daily Planet.”

In January 1968, I went to see John Mayall and his Bluesbreakers at the Whisky a Go Go for all their sets. If you were under age 18 at the time you could now get into the venue but had to first sit in the balcony upstairs. Drummer Jim Roup was also there during the booking. Stills and Young were in attendance for one show. I immediately thought Buffalo Springfield would return to the Whisky that year.

Jim Roup: It was a Saturday night, the place was packed, and there were Stills and Young standing right in front of the stage watching guitarist Mick Taylor. Neil clad in black buckskin and Stills trying to chat up some women at the club.”

Earlier during November 1967 and then in April 1968, Buffalo Springfield did two U.S. tours of the South with the Beach Boys and the Strawberry Alarm Clock.

Dennis Dragon: (Musician) I was with the Beach Boys as a percussionist/drummer augmenting Dennis Wilson on the 1968 shows. This tour was a ball-breaker. It was insane how it was booked. And that is what I think caused stress levels to go over the top, and Neil Young started having fits on the stage and tore that band apart. I saw an epileptic fit by Neil in Florida. There was a strobe light and that set him off, and it wasn’t a pretty sight on that tour, pal. I saw him almost swallow his tongue. That was a little on the rough side.

There was an incident as well on that tour that I have total recall on. We all had long hair and we went into the South. This is a time period just before the movie Easy Rider is released. When we went to get something to eat after a show we were given a certain ‘look’ at a few places. ‘Get out, you hippies’ vibe. Just a few cold stares and ‘Get the fuck out of my town.’ It might have been in Birmingham Alabama and I walked in with Neil Young and a couple of other guys after a gig, maybe 10 or 11 o’clock. We ordered and three or four ‘good old boys,’ maybe 25 feet away, and we got the ‘stare’ and I picked up the information. And the obvious instruction in front of me was, ‘You take that guy with the fringe and I’ll get the guy with the long curly hair.’ It got real uncomfortable.

“But shortly after that, Charlie Brown walked in, knowing where we were going to eat, and he was a big white fucker. Don’t mess with Charlie Brown. He was the head roadie and ‘security’ dude. And there were no words after that. Once he walked in those good old boys were outnumbered and out powered. It was scary. If Charlie had not walked in we would have been fucked when we exited that restaurant. I think that incident certainly influenced ‘Southern Man.’ No doubt.

“I watched Buffalo Springfield nightly. One thing I noticed about that band was they were very inconsistent. It was a band that depended on who was singing and what song. The vibe would change with that band from moment to moment based on who was singing. That’s what I liked about them. There was a variety and a definite persona coming off those players in that band. They were really individualistic. Neil was the most detached from the band in being himself. It was obvious he was gonna break off from them. He was not having a good time on that tour. I guarantee it. That was way too hectic for him. He was a loner, dude.

Stephen Stills came to me near the end of the tour and said, ‘I’m starting a new band. Do you want to be the drummer?’ I replied, ‘I appreciate the offer but I got to hang at the beach.’ (Laughs.)”

Doug Dragon: (Musician) I was the backup Beach Boys as coordinator and keyboardist on the ’68 shows. The thing about Neil, that I remember specifically, other than he was a brilliant lyricist, an adequate guitar player and a very nice guy, was the fact one night we were on the road and it was just before the Springfield was going to break up. I had no idea about this.

“We were sitting on the same bed in Neil’s room and he had his guitar in his hand and Neil was writing some lyrics and I said, ‘That sounds pretty good.’ It had the words crystals and chariots in it. And then Neil mentioned about a debut album he was going to be putting out on his own. I said, ‘Man, you guys are really a good group. It’s really an honor and privilege to play with you.’ I wasn’t stroking his ego. But he was very humble and nice. Neil then said, ‘There’s gonna be some changes coming down with the group.’ I didn’t know what he meant. Neil was career-minded.”

Little Steven Van Zandt: I saw Buffalo Springfield [November 1967] at a college here [in New York] with the Youngbloods and the Soul Survivors. It was a great show.”

During spring 1968, Buffalo Springfield were trapped in what looked to be a scene right out of the 1961 episode of The Twilight Zone Rod Sterling and team had written. Five Characters in Search of an Exit, based on a theme from a Luigi Pirandello play, Six Characters in Search of an Author and Jean- Paul Sarte’s No Exit.

Dickie Davis: Going on tour with the Buffalo was getting together. By that time we hardly spoke to each other while we were in town. When we were on the road everybody started playing together and going to each other’s rooms and working on songs and being friends again. And we tightened up. One of the reasons I think that Neil left the band at one point was because he didn’t want to go back on tour to get tight with them again. Because if that happened in town we drifted apart. On tour we became friends again.”

And after May 5, 1968, Buffalo Springfield voluntarily fled from their stage stable and became a mythical fable.

James Cushing: As far as Buffalo Springfield breaking up after the last show in Long Beach California, I was so into their music I was into denial they had broken up. Or I figured it was just a temporary re-arrangement. They were all alive and still living in town. I wasn’t sitting shiva for Buffalo Springfield. I was waiting for some local deejay one late night to announce their reformation.”

“The Buffalo Springfield just sort of snuck UP on everybody,” summarized drummer/writer Paul Body in a 2018 email. “From ’66 until they shattered like glass, they were everywhere or seemed to be.

“Saw them open for the Stones in the Summer of ’66. All fringe and cowboy hats. I seem to remember them doing ‘Nowadays, Clancy Can’t Even Sing.’ Saw them at the Whisky with the Daily Flash opening for them. They were just part of that magic Summer. By the time ’67 rolled around the first album was out and then there was that little riot on the Sunset Strip that the Springfield immortalized in ‘For What It’s Worth.’ Saw them at the Monterey International Pop Festival and they were pretty good. The long version of ‘Bluebird’ was played all Summer. For some reason that version wasn’t put on the album.

“It was a great look into the future, a future that never came because by ’68, there was a drug bust and they went their separate ways. For about 2 years, there was a Buffalo Springfield Stampede and then the flame was gone. For two years they were as good as it got to be.”