By Harvey Kubernik c 2014

In 1965, Levon Helm and the Hawks ((Robbie Robertson, Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, and Garth Hudson) had met up with Bob Dylan, who hired them as his back-up for what was  to be many months of savage, sinew-building road trips. Levon did not go along, however, embarrassed that his band was backing another. Mickey Jones was the drummer on Dylan’s 1966 European tour.

to be many months of savage, sinew-building road trips. Levon did not go along, however, embarrassed that his band was backing another. Mickey Jones was the drummer on Dylan’s 1966 European tour.

On July 29, 1966, just a month or so after Blonde On Blonde was in record store bins, Bob Dylan was reportedly involved in a motorcycle smash up and then spent nine months in alleged seclusion.

In 1967, Levon swallowed his pride and rejoined the Hawks in Woodstock. The others had earlier accompanied Dylan into the woods of upstate New York in search of an idyll, and there resolved to bow out of Dylan’s secondary spotlight.

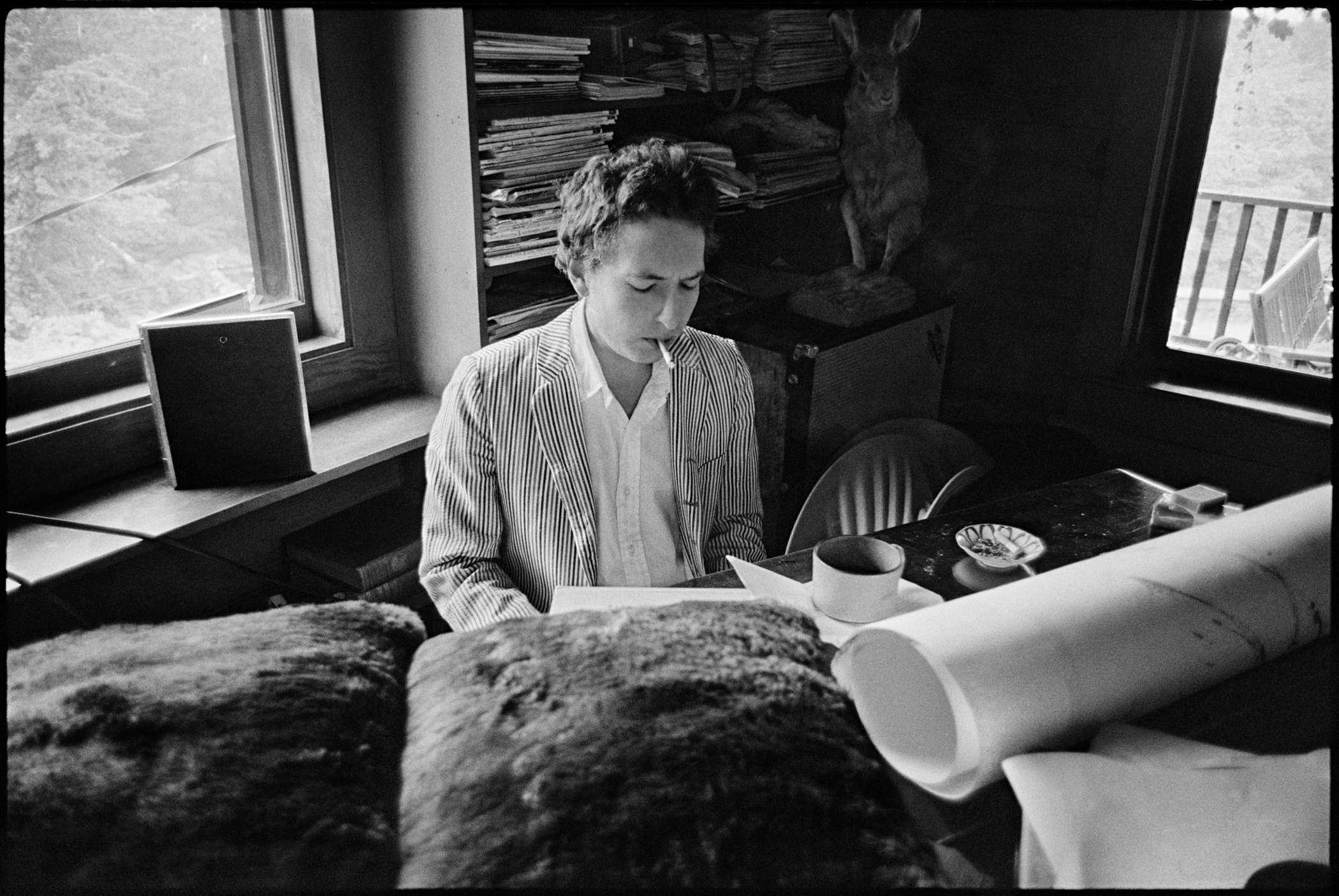

During 1967, Dylan ensconced himself with Robertson, Danko, Manuel, Hudson and, later, Helm, in the basement of Dylan’s home in Woodstock and at a small house the Band had rented in West Saugerties, known as Big Pink.

They subsequently recorded over one hundred songs, most of them originals, with Dylan on lead vocals. Later to be known as the Complete Basement Tapes.

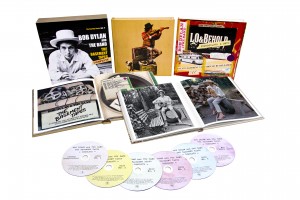

In November 2013, Bob Dylan’s The Basement Tapes Complete: The Bootleg Series Vol. 11 was finally released, along with The Basement Tapes Raw: The Bootleg series Vol. 11, a two-disc product from the deluxe edition as well as a 3 LP set pressed on 180-gram vinyl.

The Dylan and Co. 1967 collaboration yielded traditional covers, wry and comical ditties, off-the cuff takes, and, most important, dozens of newly-written Dylan tunes, including “I Shall Be Released,” “The Mighty Quinn,” “This Wheel’s On Fire” and “You Ain’t Going Nowhere.”

In late ‘67, a fourteen-song selection of those Dylan songs subsequently made the rounds as an acetate disc to various music publishers and recording artists. They were registered and copyrighted for Dylan by Dwarf Music, a publishing company he owned with his manager Albert Grossman.

During 1967, Brian Auger heard the acetate pressing of available Dylan songs in a U.K. music publishing office.

“Manfred Mann had gotten ‘Quinn the Eskimo’ first. Then I was played ‘This Wheel’s on Fire.’ It had a walking bass on it. I then grabbed the tune for us to cover,” Auger explained to me around his 2012 club date at The Baked Potato in Studio City, California.

In addition, The Byrds recorded two tracks from The Basement Tapes on their Sweetheart of the Rodeo LP, “Nothing Was Delivered” and “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere.” Their live repertoire, always including Dylan, later included “This Wheel’s on Fire.”

“Chris (Hillman) got the demos of the two Dylan songs in the mail that we did,” Roger McGuinn told me in 2007. “Dylan as a songwriter was so much better than everyone. We had been out of touch for a few years and it was interesting to notice that at this same period he was going in the same musical direction we were in.”

“I have no idea why I got in the mail the two Bob Dylan Basement Tapes songs in my mail,” added Hillman in a 2014 interview. “I sensed something was good there and I took them to McGuinn.”

“After the motorcycle accident, Dylan was off the public radar for what seemed like a couple of years,” offered music historian and writer, Kirk Silsbee. “We didn’t know it but he was holed up in Woodstock, which most of us had never heard of before the festival. That absence gave way to all kinds of speculation on his whereabouts and well-being.

“Though he wasn’t speaking for himself, Dylan had several interlocutors in the form of his songs, performed by others on the emerging FM rock radio. Peter, Paul & Mary introduced ‘Too Much Of Nothing,’ the Byrds gave us ‘You Ain’t Going Nowhere,’ ‘This Wheel’s on Fire’ was done by Julie Driscoll, Brian Auger & the Trinity, and Manfred Mann’ did ‘Mighty Quinn.’ The songs were all introduced to us by those artists, and it was a form of mental sport to try to divine some kind of secret code being sent to us from Dylan through them. I imagined him in the same kind of cloistered bunker that Thelonious Monk stared out from on the cover of his classic Underground album of 1967, furtively sending cryptic messages to the front any way that he could.”

“When I first was given a cassette tape of The Basement Tapes by Garth Hudson in the fall of 1968, I felt like it was the American version of the Soviet Samizdat–a hand-made piece of art secretly passed from hand to hand,” recalled Jonathan Taplin, former manager of the Band, and now, director, USC Annenberg Innovation Lab. “I think credit needs to go to Garth for recording these songs in the Big Pink basement with a rather amazing fidelity. In a sense he was following in the ‘field recording’ tradition of Alan Lomax. For both Dylan and the Band it was a way to let friends know about their new work, with none of the commercial pressures of putting out a record. And in that sense, much like the development of Be Bop during World War II when there were no recordings, a new kind of ‘Americana’ was birthed outside of any market pressures.”

“When I first was given a cassette tape of The Basement Tapes by Garth Hudson in the fall of 1968, I felt like it was the American version of the Soviet Samizdat–a hand-made piece of art secretly passed from hand to hand,” recalled Jonathan Taplin, former manager of the Band, and now, director, USC Annenberg Innovation Lab. “I think credit needs to go to Garth for recording these songs in the Big Pink basement with a rather amazing fidelity. In a sense he was following in the ‘field recording’ tradition of Alan Lomax. For both Dylan and the Band it was a way to let friends know about their new work, with none of the commercial pressures of putting out a record. And in that sense, much like the development of Be Bop during World War II when there were no recordings, a new kind of ‘Americana’ was birthed outside of any market pressures.”

What strikes me in 2014 about The Basement Tapes is that it’s a totally independent production. It has something to do with musicians talking the jazz idea of spontaneous live performance. And the hippie aesthetic idea of something organically rooted in the place time experience. And turning that from a social goal into actual behavior.

Dylan and Co. enacted that in a basement cellar garage. Instead of just writing a song about it or how great it would be to be in a functional community. They created a functional community. And it had nothing directly to do with the corporation. Not because Bob Dylan was theoretically anti-corporation. But because the music had so much coming into it and so much going on in it that it just had a whole different function.

When rumors and rare acetates of some of these recordings first began surfacing, it created a curiosity strong enough to fuel an entirely new segment of the music business and record collector world: the bootleg record.

In 1969, an album mysteriously titled Great White Wonder started appearing in record and head shops around the country, and Dylan’s music from the summer of 1967 began seeping into the fabric of popular culture.

With each passing year, more fans and sought out this rare contraband, desperate to hear this new music from Dylan.

The actual recordings, however, remained commercially unavailable until 1975, when Columbia Records issued a scant 16 of them on The Basement Tapes album (that album also included eight new songs by The Band, without Dylan).

On June 26 1975 an official double LP collection of The Basement Tapes compiled by Robbie Robertson for Columbia Records was released as Bob Dylan and the Band.

In a 1976 interview I conducted with Robertson for Crawdaddy! Magazine, I asked Robbie about The Basement Tapes album.

“All of a sudden it seemed like a good idea,” Robertson claimed. “I can’t tell you why or anything. It just popped up one day. We thought we’d see what we had. I started going through the stuff and sorting it out, trying to make it stand up for a record that wasn’t recorded professionally. I also tried to include some things that people haven’t heard before, if possible. Whether it went top ten or not didn’t concern me. I just wanted to document a period rather than let them rot away on the shelves somewhere. It was an unusual time which caused all those songs to be written and it was better it be put on disc some way than be lost in an attic.”

In the same interview, we discussed his guitar playing. Robertson had guested on Dylan’s Blonde On Blonde and I wondered about the double keyboard combination of piano and organ that became a trademark sound of the Band’s work with Dylan. Did Robbie ever feel confined by this format?

“No. I play as much as I want to play. No one is telling me, ‘Listen, you’re playing too much.’ That’s my own decision. That’s how much I prefer to do. When I hear other people play a lot more than required I find its really drivel and there’s nothing in this fuckin’ wide world that’s going to do anything for the song; I don’t care. I like a good guitar part where it adds something, has a nice place and is a nice solo. Not too much, nor too little. But I think as time goes on it just takes different proportions, and too much is unnecessary.”

Robertson’s guitar theory seems to simply extend his basic life philosophy of unhurried discipline. Or, as Bob Dylan said himself when he called to talk about Robbie for my 1976 Crawdaddy! article. “Listen to his guitar playing. That’s about all you need to know about him.”

“There was a thing that happened between Bob and the Band that when we played together that we would just go into a certain gear automatically,” Robbie explained to me in a 2004 interview. “It was like instinctual, like you smelled something in the air, you know, and it made you hungry. (laughs). It was that instinctual. And the way we played music together was very much that way. And whether, we were playing in 1966, or 1976, or when we did the tour together in 1974, we would go to a certain place where we just pulled the trigger. It was like ‘ just burn down the doors ‘cause we’re coming through.’ And it was a whole other place that we played when we weren’t playing with him. It was a whole place that he played when he wasn’t playing with us, so it was like putting a flame and oil together, or something. I don’t know.”

On July 8, 1995 at the MET Theater in East Hollywood I co-produced an evening of spoken word and music where John Densmore of the Doors and associates performed selections on stage from The Basement Tapes as part of a week-long Rock ‘N’ Roll Literature series I curated.

The Basement Tapes Complete brings together, for the first time ever, every salvageable recording from the tapes, including recently discovered early gems recorded in the “Red Room” of Dylan’s home in upstate New York. Garth Hudson worked closely with Canadian music archivist and producer Jan Haust to restore the deteriorating tapes to pristine sound, with much of this music preserved digitally for the first time.

The decision was made to present The Basement Tapes Complete as intact as possible.

Also, unlike the official 1975 The Basement Tapes product, these performances are presented as close as possible to the way they were originally recorded and sounded back in the summer of 1967. The tracks on the 2014 edition run in mostly chronological order based on Garth Hudson’s numbering system.

“The Basement Tapes, a Dylan and Band (a.k.a. Hawks, Crackers) collaboration recorded June-November 1967, were wholly concealed from public viewing hearing in ’67,” lamented Prof. James Cushing in 2013, who teaches English and Creative writing in Central Coast California on the campus of Cal Poly San Luis Obispo.

Poet Cushing is a deejay on KCPR-FM who hosts a weekly program, Lunch with Bob, Tuesdays from noon-one p.m. His most recent book is The Magicians’ Union, published by Cahuenga Press.

“If the full 5 CD 5 hour each disc set of the complete recordings was commercially released, it would be an item to get completely lost in, like an equivalent of the Harry Smith Anthology. Each song is terrific in itself and each song has a terrific relationship with every other song on it. Some are old. Some are brand new. Some are serious. Some are funny. Some are Biblical. Some are sort of silly and some are excuses to crack up. But you get the sense these are real human beings making real human music in a real human situation for real human purposes.

“The Basement Tapes Complete are like a whole shadowy subterranean alternative career for Bob Dylan. It’s as though somebody discovered that while James Joyce was writing Ulysses and Finnegans Wake, he also wrote two other novels that were completely finished but put them in a trunk,” Cushing concluded.

“It’s hard to believe that at the peak of ‘psychedelia’ Bob Dylan was hunkered down in the backwoods with a cohort of grizzled fur trappers who looked like extras from ‘How The West Was Won,’ ventured Kenneth Kubernik, musician, author and a contributor to Variety.

“His own speed-addled phase played out, it was time for Dylan to craft a new musical identity, still lyrically symbolist but grounded in the loamy soil of juke joint blues, hillbilly folk, tin-pan saviness and the steely authority of master musicians/artisans growing a new material that appeared both timely and timeless.

“It’s been nearly a half a century since The Basement Tapes surfaced and we’re still coming to grips with the scope of their influence, like a king’s harvest for epicurean ears.”

“Like far too many anxious fan(atic)s I would wager, my first exposure to something called The Basement Tape – singular – came via a 1969 article in Rolling Stone,” admits part-time Dylanologist and full-time admirer Gary Pig Gold. “That immediately propelled me out of chemistry class and into downtown Toronto, to the big flagship Sam The Record Man store: But all that could be found in my uneducated hunt there were some semi-legal Rare Batch of Little White Wonder LPs imported from Italy, I believe. No dice.

“Then in 1975 came something pretty official looking from Columbia Records itself called The Basement Tapes. Yet even to my young untrained ears these recordings sounded suspiciously updated, as opposed to upgraded, in a thoughtlessly Malibuesque Planet Waves kinda way (damn you, R. Robertson!) …again, I was wondering what all Greil Marcus’ raving about in that old Stone was actually for in the first place.

“It wasn’t until the dreaded mid-Eighties, thanks to a then flourishing network of, um, tape traders who were stepping up to do what the music industry couldn’t be bothered to, that I finally began to find, hear, collect and duly treasure THE REAL THING. As in those majestically raw-boned, un-tinkered-with, expertly Garth Hudson-engineered, subterranean West Saugerties jewels. Dozens upon dozens of them, in fact! Some funny, some smart; some long, others quick, all basically indescribable …especially when placed within their proper historical – as in Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band perspective. Yes, these here were songs and sounds unlike anything else at all being made anyhow by anyone, anywhere, in 1967. Not to mention 1975, 1987, or of course 2014.

“And so, lovingly curated by proud Torontonians Jan Haust and Peter J. Moore right there in the shadow of Rompin’ Ronnie and the Hawks’ old Yonge Street stompin’ grounds, today The Basement Tapes unspool anew so thankfully unspoiled, with all their big pink and bluesy splendor intact. Like some sort of David Lynchian deep woods, behind-the-midway counterpart to Brian Wilson’s concurrent SMiLE sessions, Dylan and his cracker Band had unknowingly – or then again, maybe not? – tripped open a lyrical and sonic portal into a distant past which was, in fact, a glimpse towards hitherto unimaginable futures. Biblical, you may ask? Well, only in a Jerry Lee Lewis way I reckon. But parables of pure, impudent rock ‘n’ rolling nevertheless.

“The Basement Tapes, in this latest and by far greatest incarnation, should indeed continue to be savored and studied for immeasurable years to come. If you haven’t already, now you know where to start.”

One thing The Basement Tapes Complete certainly reveals is the shadow of Johnny Cash that loomed over the recording activities. Three Cash songs: “Belshazzar,” “Big River” and “Folsom Prison Blues” were cut by Dylan and the Band.

According to Tony Scaduto, author of the biography Dylan, in 1973, it was Cash’s influence at Columbia Records that helped save a youthful Dylan from being dropped by the company.

In 1975, I interviewed Johnny Cash in Anaheim, California for Melody Maker. We talked for a couple of minutes about Dylan.

“I became aware of Bob Dylan when the Freewheelin’ album came out in 1963. I thought he was one of the best country singers I had ever heard. I always felt a lot in common with him. I knew a lot about him before we had ever met. I knew he had heard and listened to country music. I heard a lot of inflections from country artists I was familiar with.

“I was in Las Vegas in ’63 and ’64 and wrote him a letter telling him how much I liked his work. I got a letter back and we developed a correspondence.

“We finally met at Newport in 1965. It was like we were two old friends. There was none of this standing back, trying to figure each other out.

“He’s unique and original. I keep lookin’ around as we pass the middle of the ‘70s and I don’t see anybody come close to Bob Dylan. I respect him. Dylan is a few years younger than I am but we share a bond that hasn’t diminished. I get inspiration from him.”

Apparently, the feeling was mutual.

Johnny Cash’s son, John Carter Cash, a music producer and an Executive Producer on the Cash film biography Walk The Line movie, and also an Executive Producer on the Cash 2007 Johnny Cash Show TV series DVD, told an amusing story describing Dylan’s initial encounter with his dad for the first time in the December 2, 2005 issue of USA Weekend.

“Dad would chuckle when he’d tell me how Bob Dylan acted like a silly kid when they first met. He burst into Dad’s hotel room and began jumping on the bed, shouting, ‘I met Johnny Cash! I finally met Johnny Cash!”

Harvey Kubernik interviews Dr. James Cushing

Q: In 2014, your wish for a complete and commercial Basement Tapes culled from 40 reels of tape distilled into 6 CD documents, has become a retail reality.

A: The real ones are finally out. For years the chosen people have had only one sixth of the Torah. And now we get the whole Torah. Paradigm shift, baby. One of the very greatest bodies of 20th century American music will finally be accessible to anyone.

“I was just re-reading The Old, Weird America [cultural critic Greil Marcus’ book-length study of the Basement Tape sessions], thinking again that this 1997 book offers authoritative liner notes for an album that was recorded in 1967 but not released until 2014: a 47 year lag! That’s an extraordinarily long period of time in the world of entertainment, like five generations.

“The 2014 release of The Basement Tapes Complete also brings up the problem of that 1975 double LP, which presented a little more than 10 per cent of the original Basement Tapes, interspersed with eight demos by the Band that were recorded much later in different circumstances and re-mixed by Robbie Robertson into mono, even though they were originally recorded in stereo. ‘I Shall Be Released’ and ‘The Mighty Quinn’ were rather conspicuously missing from that double album, and I still wonder why. Mind you, I am glad the 1975 album exists for the eight Band songs, especially ‘Bessie Smith.’ And it was as close as we could come for many years to getting access to this mysterious body of music.

“That mysteriousness is one of the reasons, as I remember very well, why the debut LP from the Band, Music from Big Pink, was so eagerly awaited in 1968. I bought Music from Big Pink with my high school allowance money without hearing a note of it purely because I had read these were the guys who were working with Bob Dylan on those secret sessions. And I noticed there were a couple of tunes credited to Bob Dylan that I didn’t recognize. I hadn’t heard a Bob Dylan song called ‘Tears of Rage.’

Q: With this 2014 multi-disc package, we have yet another stellar example of the Dylan and Band relationship. Why do they work do well together?

A: Why do Bob and this group work so well together? You could ask the same question about the Beatles or the Stones or the John Coltrane Quartet. They work together because it’s that combination of that personalities at that moment of their lives intersecting at that moment of cultural history, employing that particular style of music as a language to express and represent their sense of everything that’s going on. Usually, that doesn’t work out. When it’s does and documented, it’s a miracle.

Q: Dylan might have indicated in some interviews or comments that these recordings were first done for song publishers or music associates to acquire cover versions of his songs: Peter, Paul & Mary, Manfred Mann, the Byrds, Brian Auger and the Trinity, and the debut Band LP. But, now we know that’s not the total story.

A: It seems deeper than that. I see it as a template for many of the albums he would go on to make. Everyone talks about the change that showed up in Dylan’s music after John Wesley Harding, but the seeds of this change were planted in The Basement Tapes. Although many of the songs have a surreal and sometimes comical edge to them (‘Yay Heavy and a Bottle Of Bread,’ ‘Tiny Montgomery,’ ‘Please Mrs. Henry’), we don’t get very far into disc one before we discover ourselves in country-western land.

Now, everyone knows most of Blonde on Blonde was recorded in Nashville in 1966, but that doesn’t make Blonde On Blonde a country-western record by any definition of that term. However, now that Dylan is out of Nashville, all of a sudden the Johnny Cash and the Hank Williams songs all suddenly come out. Dylan’s voice so nicely anticipates not John Wesley Harding, which was done months later, but Nashville Skyline, which was done two years later. So that’s remarkable. You realize how deeply indebted he is to Johnny Cash. If the Basement Tapes are a costume party, they seem to have come as Merle Haggard and the Strangers.

“The loud raucousness of some of the rock songs anticipates some of the Before The Flood and Rolling Thunder tours. And many of the songs have a gospel feel to them, thanks to Garth Hudson’s gospel keyboards. Garth reveals in the liner notes that, when they were recording the Basement Tapes, they were mostly listening to gospel 45’s from the ’50s. Of course, Johnny Cash’s ‘Belshazzar’ tells a bible story. So if you want a bridge between Highway 61 and Slow Train Coming, well, there it is.

“Since Time Out Of Mind in 1997, Dylan’s been mining various traditions, images, situations, and tropes from the whole lexicon of American folk music. And that’s what the Basement Tapes does, too: This sampling of different traditions. You’ll hear jump blues and murder ballads here and on Tempest. The traditional folk tunes like ‘The Auld Triangle’ stand only a few inches behind all the songs that Dylan is writing today.

Q: On the Basement Tapes, Bob Dylan sings with five or six different voices. Experimenting with the Band on tempo.

A: Dylan shapes his voice for the needs of each song like an actor going into a different part. He’s always done that. The early reviewers of his live act who noticed some connection with Charlie Chaplin were on to something. Chaplin could take on all sorts of different characters while remaining himself. And, Dylan does that on this album to an extraordinary degree. There’s one song that is almost shockingly accurate to the voice that he has on Nashville Skyline. It’s like he’s had the Nashville Skyline voice in somewhere in his head or down in his larynx or in his nose, or where he had it the whole time.

“A Basement cover of ‘See That My Grave Is Kept Clean’ (author Clinton Heylin guesses Sept. ‘67) is the first appearance of the higher and more ‘musical’ Nashville Skyline voice. Griel Marcus has an inspired page on it in The Old Weird America.

Q: Is there any other album set or a reissue or a un-discovered tape that can possibly be compared to The Basement Tapes Complete? In terms of hidden secrets being revealed or a mysterious album becoming available years after it was taped?

A: In the early 90s, Impulse released a 4CD box set called John Coltrane Live In Japan. The 1966 group with Alice Coltrane, Pharaoh Sanders, Jimmy Garrison, and Rashied Ali played several shows in Japan, and two were broadcast on Japanese radio. Alice Coltrane has confirmed that, while everyone in the band knew these concerts were being broadcast, no one realized they were being recorded as well. Because of language and translation difficulties, they did not understand that a safety tape was being made. As a result, there’s a freedom there like nothing else in his records. ‘My Favorite Things’ is 57 minutes. Part of one concert came out in fake stereo in 1973, then the whole body of music comes out in 1991, twenty-five years later.

Q: Can you describe what this Basement Tapes Complete collection means to you?

A: It’s a kind of magical, sacred object, actually. I sort of have to be careful with it. Sony Music seems to be treating Bob Dylan like their living equivalent of Miles Davis, releasing big box sets of items that people wanted for years. Like Miles’ Cellar Door 1970 box.

“Dylan and the Band command our attention on this album in a wonderfully paradoxical way: by completely ignoring us. There’s no audience there in that room but the ghosts of American music. By focusing on all of the tributaries of American music and the wonderfully surreal braiding of those tributaries in Dylan’s own mind, they make original American meaning. And they do it every bit as well as Blonde On Blonde and John Wesley Harding. Only those are cups, and this is an ocean.

“I’ve often thought that if ‘Get Your Rocks Off’ had been included on John Wesley Harding that the entire history of the sixties might have been different (laughs).

Q: How will this formal and label-sanctioned The Basement Tapes Complete impact the view of Dylan’s overall body of work?

A: I hope The Basement Tapes Complete forces a re-assessment of Bob Dylan’s early period. Most of the time, people think about Dylan’s ‘early’ period in terms of acoustic versus electric or as pre-accident and post-accident. But I think with this new 6CD box, the situation may change.

“I see Bob Dylan’s first period as 1961 to 1971, with the first album and Greatest Hits Volume 2 as bookends. The peak of this period ran from 1965 to 1967, and is represented by Highway 61 Revisited, Blonde on Blonde, The Basement Tapes Complete, and John Wesley Harding. Those last two albums prove that 1967 was, by far, Bob Dylan’s most productive year.

“It’s such a huge addition to the Dylan library. The total playing time is equivalent to all the Beatles’ albums from Please Please Me to Sgt. Pepper. So it will take a long time before people absorb all of these songs and their originality. I think the trajectory of Bob Dylan’s career is going to have to be re-explained.

Q: What revelation is further apparent after absorbing The Basement Tapes Complete.

A: On The Basement Tapes Complete, Bob Dylan fully realizes his genius. Everything that is implicit in in all of his best work, from Freewheelin to Blonde On Blonde, is completely brought into presence. He and his intuitively tuned-in group of musicians are entirely free to do anything they want. The atmosphere blende the relaxation of being off the road, Dylan’s changing relationship with Albert Grossman, the presence of Sara and the kids, the joy of being in nature after living in New York City a long time, the euphoria of marijuana instead of any other harder drugs, and a lot of deep, deep memories of old folk, country and blues tunes that he had known and heard and learned at some of the originators’ feet in 1961 and 1962.

“There’s a way in which Bringing It All Back Home would be a more accurate title for The Basement Tapes Complete. All of Dylan’s original surrealist brilliance, and all of his range of knowledge of blues, folk, country and traditional music, and all of the ways those sensibilities blend into something new, and all of his give-and-take with other musicians – this album just catches it at its most intimate.

“The wisdom and information in these batch of songs! Dylan was a very old 26 year old! There’s always mystery to artistic inspiration, but we know that Allen Ginsberg visited him while he was recuperating and brought him poetry books to read: Rimbaud, Shelley, Wordsworth, and Whitman.

“People who visited the house reported a rather large type and illustrated bible in the living room. A scriptural vibe is in many of the lyrics, and a whole lot of things are happening at a mythic, William Blake level underneath the words.

“I’ll go out on a limb. The Basement Tapes Complete is Bob Dylan’s greatest album. It’s got the maximum level of Dylanesque poetic and musical intensity, and it’s funny and serious, and it sustains itself for over six hours.

A related companion album of Bob Dylan 1967 long-lost songs produced by T Bone Burnett was also released in November, Lost On The River: The New Basement Tapes.

20 Dylan lyrics now fully realized with music and studio performances from Elvis Costello, Rhiannon Giddens, Taylor Goldsmith, Jim James and Marcus Mumford issued on Electromagnetic Recordings/Harvest Records (Capitol Music Group) that will be accompanied by a Showtime documentary titled, Lost Songs: The Basement Tapes Continued, directed by Sam Jones.

“The discovery of these previously unknown Bob Dylan songs that were thought lost since 1967 is the stuff of Hollywood fiction and a find of truly historical proportions,” said Jones. “It is a unique opportunity to film T Bone and these great artists as they collaborate with a young Bob Dylan, and each other, to create new songs and recordings. These days and nights in the studio have been nothing less than magical.”

Jones will weave these studio sessions into a broader narrative that will incorporate the stories behind the original Basement Tapes, expound on their cultural significance and chart their enduring influence.

(A small portion of this story was published in the December issue of Record Collector News).