By Harvey Kubernik c 2015

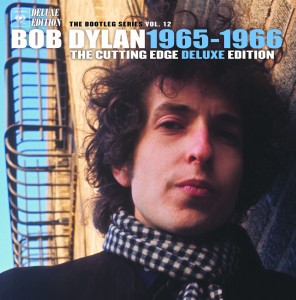

The latest chapter in Columbia/Legacy’s highly acclaimed Bob Dylan Bootleg Series focuses on the legendary studio sessions that produced Bringing  It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde On Blonde, the trilogy of album masterpieces which secured Dylan’s reputation as a songwriter and performer of unprecedented depth, power and originality while significantly impacting the course of popular music and culture. All recordings included in The Cutting Edge 1965-1966: The Bootleg Series Vol. 12 are pristine transfers and mixed from the original studio tracking tapes.

It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde On Blonde, the trilogy of album masterpieces which secured Dylan’s reputation as a songwriter and performer of unprecedented depth, power and originality while significantly impacting the course of popular music and culture. All recordings included in The Cutting Edge 1965-1966: The Bootleg Series Vol. 12 are pristine transfers and mixed from the original studio tracking tapes.

Released this past November, this 2015 Dylan product provides a rare exploration into his creative process in the studio, allowing hardcore fans and consumers to truly experience another side of Bob Dylan through the evolution of his songs from this groundbreaking period.

This latest retail collection brings together for the first time many of the most sought-after recordings of the entire Dylan canon. Here, across 6 CDs, are previously unheard Dylan songs, studio outtakes, rehearsal tracks, alternate working versions of familiar hits–including the complete “Like A Rolling Stone” session–and more.

The Cutting Edge 1965-1966: The Bootleg Series Vol. 12 is available in a 2CD or 3 12″ vinyl LP set and brings together some of the musical high points of the deluxe and super-deluxe units.

An 18CD Collector’s Edition of the package has been issued and available exclusively on bobdylan.com.

Limited to a worldwide pressing of only 5,000 copies, this 18CD edition incorporates every note recorded during the 1965-1966 sessions, every alternate take and alternate lyric. All previously unreleased recordings have been mixed, utilizing the original studio tracking tapes as the source, eliminating unwanted 1960s-era studio processing and artifice.

The 18CD edition includes Dylan’s original nine mono 45 RPM singles released during the time period, packaged in newly created picture sleeves featuring global images from the era. The limited edition houses rare hotel room recordings from the Savoy Hotel in London (May 4, 1965), the North British Station Hotel in Glasgow (May 13, 1966) and a Denver, Colorado hotel (March 12, 1966) as well as a strip of original film cell from director D.A. Pennebaker’s Don’t Look Back.

It also comes with an annotated book featuring hundreds of rare and never-before-seen photographs and memorabilia and new essays penned especially for the collection by Bill Flanagan and Sean Wilentz.

Generally regarded as three of the most important and influential albums of the golden era of 60’s rock, Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde On Blonde (a double album) were written and recorded across a span of merely 14 months (from January 1965 through March 1966) with producers Tom Wilson (Bringing It All Back Home, “Like A Rolling Stone”) in New York and Bob Johnston in New York (Highway 61 Revisited) and Nashville (Blonde On Blonde).

“On the day Dylan stepped into the studio to begin the sessions documented, he had spent less than three weeks (20 days) working in a recording studio during his 24 years on earth,” reinforces filmmaker Michael Hacker.

“Every generation falls in love with itself – their fashion, their politics (or lack thereof), their drugs, their movies – but nothing defines its sense and sensibility like their music,” declares author Kenneth Kubernik. “And, like the ‘never ending tour,’ the never-ending debate over which decade can lay claim to having the hippest sounds marches on like a May Day parade, lockstep, impervious to reason, impassioned and ultimately irreconcilable. But I’ll be goddamned if anyone is ever going to convince me that was or will ever be a more transcendent moment in music than the whip crack downbeat introducing ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ to a cohort of anxious ears fine-tuned to their AM radios in the summer of ’65.

“I can still recall hearing for the first time that, yes, ‘jangly” rhythm,’ Paul Griffin’s strutting octaves, Al Kooper’s eruptive organ, all keenly pitched to Dylan’s anthemic wail. Chilling, absolutely chilling,” he marvels. “Like a blast of rolling thunder, ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ not only signaled a change in Dylan’s direction, it revivified pop music, forcing artists to reexamine the possibilities afforded them creatively, commercially and most importantly, critically.

“Yes, the rock music critic is born in the wake of Dylan conferring upon the form a level of rigor, musically and lyrically, that elevates the appetites of teen-age America from mere consumers to denizens of a new world order,” continues the wordsmith. “If that sounds a trifle grandiose, then you weren’t there, you didn’t feel the crackle of excitement, the sudden awareness that the song emanating from you little Philco transistor was as transformative as Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, as Ornette Coleman’s residency at the Five Spot. The albums that followed, Highway 61 (Revisited) and Blonde On Blonde confirmed the scope of Dylan’s impudence.

“Fifty years later we’re still reeling (and rockin’) from that annus mirabilis- ’65/’66. Let’s see how the current generation’s music fares half a century hence.”

In 2001 and 2013 I talked to Al Kooper about his 1965 and ’66 recordings with Dylan.

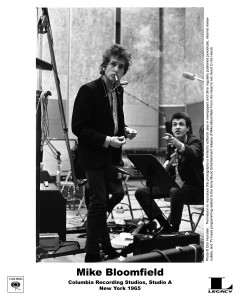

Q: Talk to me about guitarist Michael Bloomfield.

A: Well, Michael [Bloomfield] and I met on the ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ session. I had read about him in Sing Out Magazine, and saw a picture of him where he looked a little more rotund then he was when I met him. His brother says he was a fat kid growing up. So we met on the ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ session and really hit it off. So we played together on that.

“I was supposed to play guitar on that record. I packed up my guitar when I heard him warming up. It never occurred to me that somebody my age, and my religion could play the guitar like that. That was only reserved for other people. It never even occurred to me that that was an option for someone my age and my color. I had never seen that, or heard that up to that day.

Q. And you brought bassist Harvey Brooks into that session as well.

A. That’s right. So, that pretty much ended my guitar playing by and large. I said, ‘well OK, he’s as old as me and he can play like that. I’m never gonna be able to play like that. Thank you, goodbye.’ And, you know, I ended up playing organ on that record, and then I became a keyboard player really that day. So, it was a damn good thing because, you know, that was competition I couldn’t deal with.

Q: I think the star, or the secret sauce of the Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde On Blonde sessions was Paul Griffin. I know he was on some records by Garnet Mimms and on Chuck Jackson’s “Any Day Now.”

A: A big influence on me as well! Paul Griffin came from the Baptist church. On Highway 61 we did the tracks to ‘Tombstone Blues’ and ‘Queen Jane Approximately’ in one day.

“The best thing I can say about Paul Griffin is take five minutes out of your busy day and get a time where you have nothing to bother you at all. Find a real nice stereo system and sit back and put on ‘One Of Us Must Know’ from Blonde On Blonde. And just listen to the piano…And tell me if you can find on a rock ‘n’ roll record anybody playing better than that. And I would really like to hear what your decision is. To me it is the greatest piano achievement in the history of rock ‘n’ roll. I don’t hear anything than him playing the piano when I hear that record. And I’m thrilled that I’m playing organ but I’m embarrassed. And I think that Dylan should be embarrassed too. ‘Cause Paul just steals that fuckin’ record. It’s the most incredible piano playing I’ve heard in my life. If you’re a piano player try playing that note for note. It’s just incredible.

I played the organ on ‘Like A Rolling Stone.’ Paul Griffin on piano was so brilliant. He plays amazing things. And the thing that is really eye-opening about it, are the drums. Bobby Gregg, who had a hit record with ‘The Jam.’ Besides Michael’s playing, you can really hear the drums of Bobby.

Q: What is so unique about Bob Dylan’s piano playing?

A: No one talks about his piano playing because they don’t know. Bob had a very unusual way of playing in that he didn’t use his pinkies. So both his pinkies were up in the air when he played the piano. And very interesting to me. It was very interesting looking to watch that. I used to really kick a kick of that.

“The other thing was, by then, we were friends. We had spent a lot of time together. Off hour time together. Just sitting around bars and shit like that. Going to the movies and all this kind of stuff, so it was a much more comfortable situation and Robbie Robertson came to. Robbie and I split a room together. So Bob brought Robbie and I for his comfort level, rather than just go in there cold. You know what I mean?

For a March 1976 Crawdaddy! magazine cover story, I interviewed the Band’s Robbie Robertson. I asked him about his playing guitar with the group and recording and touring with Bob Dylan.

“It was an unusual time which caused all those songs to be written. We know the technique very well. We’ve been playing with Bob for years. There’s no surprises involved.

There was a thing that happened between Bob and the Band that when we played together that we would just go into a certain gear automatically. It was instinctual, like you smelled something in the air, you know, and it made you hungry. (laughs). It was that instinctual. And the way we played together was very much that way.

“I play as much as I want to play. No one is telling me, ‘Listen, you’re playing too much.’ That’s my own decision. That’s how much I prefer to do. When I hear other people play a lot more than required I find it really drivel and there’s nothing in this fuckin’ wide world that’s going to do anything for the song. I don’t care. I like a good guitar part where it adds something, has a nice place and is a nice solo. Not too much, not too little. But I think as times goes on it just takes different proportions, and too much is unnecessary.”

Robertson’s guitar theory seems to simply extend his basic life philosophy of unhurried discipline.

Or, as Bob Dylan said, when he called to talk about Robbie: “Listen to his guitar playing. That’s all you have to know about him.”

Countless musicians have covered Bob Dylan’s repertoire over the last six decades. There have been many tribute events and albums showcasing his copyrights.

Critically acclaimed singer-songwriter guitarist and multi-instrumentalist Jackie Greene, hailed by The New York Times as “The Prince of Americana,” just released his first studio album in five years, his Yep Roc Records 2015 debut, Back To Birth.

In 2013, Greene joined the reunited Black Crowes as lead guitarist on the global tour, and in 2014 released the self-titled debut album of Trigger Hippy, which Greene is a member of along with Joan Osbourne and Steve Gorman. Greene continues to be a frequent member of Grateful Dead bassist Phil Lesh’s touring ensemble Phil Lesh & Friends, contributing lead guitar and vocals since 2007. Jackie also gigged as part of WRG, an acoustic trio with Bob Weir of the Grateful Dead and Black Crowes front man Chris Robinson, and he played with Levon Helm at Helm’s memorable Midnight Ramble shows.

Back in 2004, Greene was the bandleader on a Dig Music live album from Marilyn’s in Sacramento, California, Positively 12th and K: A Bob Dylan Tribute which is billed to Jackie Greene/Sal Valentino & Friends.

An energetic cover of “Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window” is one of the high points. Over the years Greene has continued to include Dylan compositions in his concert repertoire, including “Fourth Time Around” and “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight.”

Jackie called me on the telephone and we talked about Dylan’s catalog, his memory of hearing Blonde On Blonde and his thoughts on The Cutting Edge 1965-1966: The Bootleg Series Vol. 12.

“I’ve played ‘Please Crawl Out Your Window’ on stage. Initially I heard one of the original versions of it that had the cool cow bell thing that was going on. I thought it was funky. And thought ‘that’s a cool live song.’ Something grabbed me and I thought, ‘Oh my God! This is some little white kid being funky.’

“Over the years I’ve done tons of Dylan songs in my live shows. I would choose Dylan tunes that resonated with me. I remember doing ‘Fourth Time Around’ from Blonde On Blonde. I’ve done it a couple of times. I just love that song. I think it’s a really hip cool song.

“I didn’t collect a lot of records until I was older and could afford them. I heard Bringing It All Back Home and some of the earlier stuff. It sounded like a rock ‘n’ roll guy. And then I heard ‘Blonde On Blonde. And, at first, I actually didn’t like it as much. Because I thought it sounded bad. Like the recording sounded bad. And then I got really into Bringing It All Back Home. ‘Cause I thought the recording sounded better, the songs were a little bit more digestible.

“But I remember then I started smoking pot. (laughs). And then I got into Blonde On Blonde and that kind of blew my world wide open. And I was like, ‘It sounds great!’ What the fuck is wrong with me?’ (laughs). I don’t remember how or why it happened but it totally changed my mind about it. It sort of became like one of those records as a staple. It’s like a staple in their collection, you know what I mean? It’s like a placeholder.

“I like Highway 61 Revisited and ‘Like A Rolling Stone.’ All of it. And they’re all great songs. And as someone who loves Dylan, you dig a little bit deeper into the records. And then you are directed to the Band’s Music From Big Pink. That’s how I discovered the Band. I heard the name as a kid but never really knew the association with Dylan. ‘OK. Let’s check this out.’ And then, the thing I know, the second Band album becomes one of my favorite albums of all time. ‘Holy shit!’

“As for the Dylan box set and all the sessions being available from the three albums. I think at this point now though, it’s like fifty years after the fact, I think it’s perfectly OK. I mean those albums have been digested for so long that I think people who are really interested in them are interested in how they’re made. It’s definitely a niche audience for people who are gonna buy the full set, for sure. I think that’s OK. I think it fine.

“For me, I personally like to hear demos because I like to know that people are human and people make mistakes. (laughs). Then you hear the finished thing and it makes you feel better as an artist. Like the Beatles just didn’t come out with Abbey Road. It just didn’t magically appear. You know what I mean?

“It shows you that these artists are human and that they are not always perfect. Like the recordings that we thought we think are perfect in every way it takes work to get there. And I think that’s an important thing for people to know. So I’m not against it at all. I think it’s great.”

Poet/professor James Cushing began his radio career as a late-night deejay at KPFK-FM in 1981. He has taught literature and creative writing at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo since 1989, and has continued broadcasting on KEBF-FM where he currently hosts a jazz program, Miles Ahead. Previously on KCPR-FM, Cushing once helmed a weekly program, Bob Dylan’s Lunch.

He served as Poet Laureate of San Luis Obispo from 2008-2010. Poems of his appear in many magazines and journals, and his poetry collections include The Length of an Afternoon” Undercurrent Blues” Pinocchio’s Revolution, and The Magicians’ Union, all from Cahuenga Press in Los Angeles.

In an email correspondence, I asked the good Prof. to list some initial observations he had about Dylan’s The Cutting Edge 1965-1966: The Bootleg Series Vol. 12

1. Central California Coast poet Dian Sousa published a book in 2013 called The Marvels Recorded in My Private Closet. The Collector’s Edition is a private closet, an enclosed, secretive space that contains three marvels: each of the three 1965-66 albums, Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited, and Blonde on Blonde, in their step-by-step, individual and collaborative, making.

2. Perhaps it goes without saying that only about 5,000 people worldwide would want to spend this much time and energy studying alternate takes,

false starts and breakdowns. No casual listener needs sixteen takes of ‘It Takes a Lot to Laugh,’ twenty-two takes of ‘Please Crawl Out Your Window,’ or a whole 55-minute CD of ‘Like A Rolling Stone.’ Of course, this means the listenership for this huge box is self-defining. If you’re hungry to hear how these songs were created – if you want the fullest possible picture of a powerful and historically important creative process as it took place – nothing else will do. You’ll have to pony up the $600 and surrender to what the FedEx man delivers you.

3. The FedEx man delivers you a box the size of a religious icon. It contains layers of highly charged content in different forms: sheets of thin vellum paper, thick books of glossy photos, 7” 45rpm records with an adapter, a strip of film from a print of Don’t Look Back, and eighteen compact discs with detailed information.

“Geoff Gans, the man behind the package’s design, ladles shockingly vivid photos and reproduced lyric manuscripts and period ads into a compelling slide-show portrait of an artist as a young and confident man. The remastering of the discs is equally vivid; this music has never sounded as clear and present, even on the 2003 SACD reissues of these LPs.

4. I slide in Disc 5, which in sixty-nine minutes tells the tale of three songs. ‘It Takes a Lot to Laugh’ starts as a quick shuffle, and gets put aside after three attempts. The group switches over to ‘Tombstone Blues,’ which grows faster and nastier over its twelve takes. After the master, Dylan then returns to ‘It Takes a Lot to Laugh,’ this time as a slow blues. The disc ends with the twelve-take growth and delivery of ‘Positively 4th Street.’

“All this means that three of the songs I have known all my life are now captured and presented as they existed in the precarious moments of becoming what we know them to be. The feeling is like going back in time to 1965, before I made most of the choices that have determined my adult life, and hearing an audible image of roads not taken. Take 9 of ‘Tombstone Blues,’ with backing vocals and slightly different words (“John the blacksmith” instead of “John the Baptist”), asks me to contemplate any number of What Ifs in my own life. By the time we get to the familiar master (take 12), I have started to understand the ancient idea of destiny.

5. Some of the words change from one version to another. So the songs are still in process of their being worked out musically they are also being worked out lyrically. With some exceptions, in every case Dylan brings his own private lexicon of images. Mythic and circus images and literary and fantasy images swirling them into this marvelously surreal stew that has the effect of those of us who partake in it the energy to explore our own subjectivities.

6. I think the meaning of many of the songs has much to do with how one can explain the statement they make then it has to do with that the way the song gives every listener a kind of permission to explore his or her own private imaginative world and take it seriously to present it to others. Bob Dylan gives people permission to speak. And permission to sing,

7. This box presents the gestations and deliveries of three masterpieces. Three works of genius. And yes, I know in most of the cases people don’t want to see the screaming labor. This is the way those songs were created and finished as songs and the creation of the songs was the bulk of the creative process. But there was one more step in the creative process. Which was Dylan choosing which version to put on the album and sequencing the album. Now we get to see and hear how each one was created as an individual.

8. The complete collection it has very much the same effect as the discovery of an author’s draft manuscripts on the way to the finished poem or story or novel or play. William Blake’s manuscripts for the Songs of Innocence and Experience have a number of verses for ‘Tiger, Tiger Burning Bright’ that were considered for the poem and then crossed out.

“Dylan takes the idea of modern poetry, which is that the poem is a dramatic monologue, spoken by a character and whatever the character is talking about the character is also describing his own interior state of mind. Which includes his analysis of society. That’s what Walt Whitman is doing. That’s what T.S. Elliot is doing. That’s what Ezra Pound is doing. And that’s what Bob Dylan does. So the character that Dylan creates in these albums is one that he is perfectly suited to play. And he plays it magnificently.

“In 1965 and 1966, as a young teenager, I remember thinking, as Highway 61 Revisited played on my Dynavox, “I will be listening to this album the rest of my life.” It was possibly my first adult moment. I feel that about The Cutting Edge Collector’s Edition. It isn’t an album to be reviewed. It’s raw material for doctoral dissertations.

“There will be no greater rock album released in the 21st century.”

I might have to agree with my good friend.

Even the 2-CD and 6 CD packages are remarkably dramatic and absorbing listening experiences. It had the uncanny side effect of making me look back at my life and asking “well what if I had done this turn or that turn.”

Even the 2-CD and 6 CD packages are remarkably dramatic and absorbing listening experiences. It had the uncanny side effect of making me look back at my life and asking “well what if I had done this turn or that turn.”

I feel I am closer to the mystery of Bob Dylan’s creativity than I have ever been in examining or checking out his body of work.

These 2015 retail market multi-format Dylan products are examples of the magician showing us all his tricks and after he shows us his tricks we still have no idea how he does it. Bob Dylan’s mystery is most exposed and most intact.

The record producer Tom Wilson once mentioned something along the lines about Bob Dylan in the recording studio, “He becomes a white Ray Charles with a message.”

I suggest a listen to the Ray’s 1959 recording “I Believe to My Soul,” which has more than a passing musical and keyboard influence on Dylan’s “Ballad of a Thin Man.”

Also apparent is the sonic impact of the Smokey Robinson-penned “My Girl,” a number one hit record in early 1965 that informs Dylan’s “Queen Jane Approximately.”

I brought this up to Al Kooper, who has also recorded three Robinson tunes.

Al replied, “One of my favorite things is when I called (Bob) Dylan one day and said, ‘Hey…What are you doing?’ ‘Eating a piece of toast and listening to Smokey Robinson…’ So, that makes a lot of sense.”

Jerry Schatzberg’s cover for Blonde on Blonde must have worried a lot of squares at Columbia Records. I’m pretty sure it was the first “rock” album not to have the artist’s name or the album’s name printed anywhere on the front or back – the cover has virtually no printing at all. Dylan’s face became the “word” on the cover. If you know the word, you’re in…

Furthermore, this was the first time to my knowledge that an album cover photo was deliberately out of focus.

“Almost a year earlier, Robert Freeman had elongated the Beatles’ faces on the cover of Rubber Soul (and omitted the group name), but despite that distortion, the focus was sharp, and the meaning clear: The Beatles were stretching their ambitions,” presents Dr. Cushing.

“Dylan and Schatzberg made a more radical move, and it fit Blonde on Blonde as well as Freeman’s move fit. Schatzberg’s Dylan is captured in an ambiguous moment of blurring; the subject is veiling himself in an urban shimmer. The face on the album cover is ‘in motion,’ suggesting the constantly shifting perspectives of ‘Visions of Johanna’ or ‘Stuck Inside of Mobile.’ Dylan’s scarf and hair are as large as his face, and the viewer’s eye goes up and down the image, trying to read the man’s expression through his veiled eyes.

“Does anyone still make those tan suede coats with the long buttons? Can I get one? They were way cool in 1966 and I say they’re way cool now.”

Photographer and multi-media artist Jerry Schatzberg was born in New York and attended the University of Miami. His fashion photo portraits were published in Vogue, Esquire, Glamour, McCalls, and LIFE magazine.

In the late fifties and during the sixties, Schatzberg would photograph LaVerne Baker, Eric Dolphy, the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, the Beatles, Andy Warhol, Roman Polanski, Fidel Castro, Jimi Hendrix, Mama Cass Elliot, Wilson Pickett, Faye Dunaway, Andrew Loog Oldham, Steve McQueen, Arlo Guthrie, Aretha Franklin, Chico Hamilton, Francis Copploa and Frank Zappa.

He directed some television commercials before he made his debut as a movie director in 1970 with Puzzle of a Downfall Child” His second directorial job was The Panic in Needle Park, starring Al Pacino followed by Scarecrow, co-starring Pacino and Gene Hackman. His storied film career is well documented.

In 2006, Genesis Publications published Thin Wild Mercury Touching Dylan’s Edge.

Jerry Schatzberg and Harvey Kubernik Interview

Q: Comments people have given you over the years about the front cover of Blonde On Blonde.

A: Everybody was trying to figure out what kind of drug trip we were trying to portray since it was out of focus. Nothing to do with that. It was January. Dylan had on a light jacket and I just had on a light jacket and a number of the images while we were moving around were moving, you know. So they were blurred a little bit. I must say Dylan chose that one and I was delighted. I knew there are a number of other good images from that shoot that were quite good which I use now. For a while I used just the Blonde On Blonde cover. But now, at shows and different places, I show them. They are quite good and absolutely sharp. But people thought we were trying to say something more than what we were.

I think any photographer that photographs another person tries to capture that person as best he can. By this time I knew Dylan quite well. I’d been photographing him for about a year. We’d hang out together and go places. When you’re in that kind of a relationship you are getting into somebody’s soul.

That as one thing. A lot of people want to know where it was photographed. To the best of my recollection it was a meat packing district in Manhattan which I had gone over a number of times to find out exactly where and it just doesn’t exist anymore. So it was either a building that was torn down or totally surfaced and I have no idea. Sony is now in the process of doing a search on a number of albums and where they were shot in New York. Two weeks ago we went down to the meat packing district with a camera crew and Sony looking for it. But we found a couple of places they might have. I liked the meat-packing district in contrast to Dylan. I felt that would be a good place to shoot.

Q: Did Dylan translate differently in your black and white photographs as opposed to color sessions?

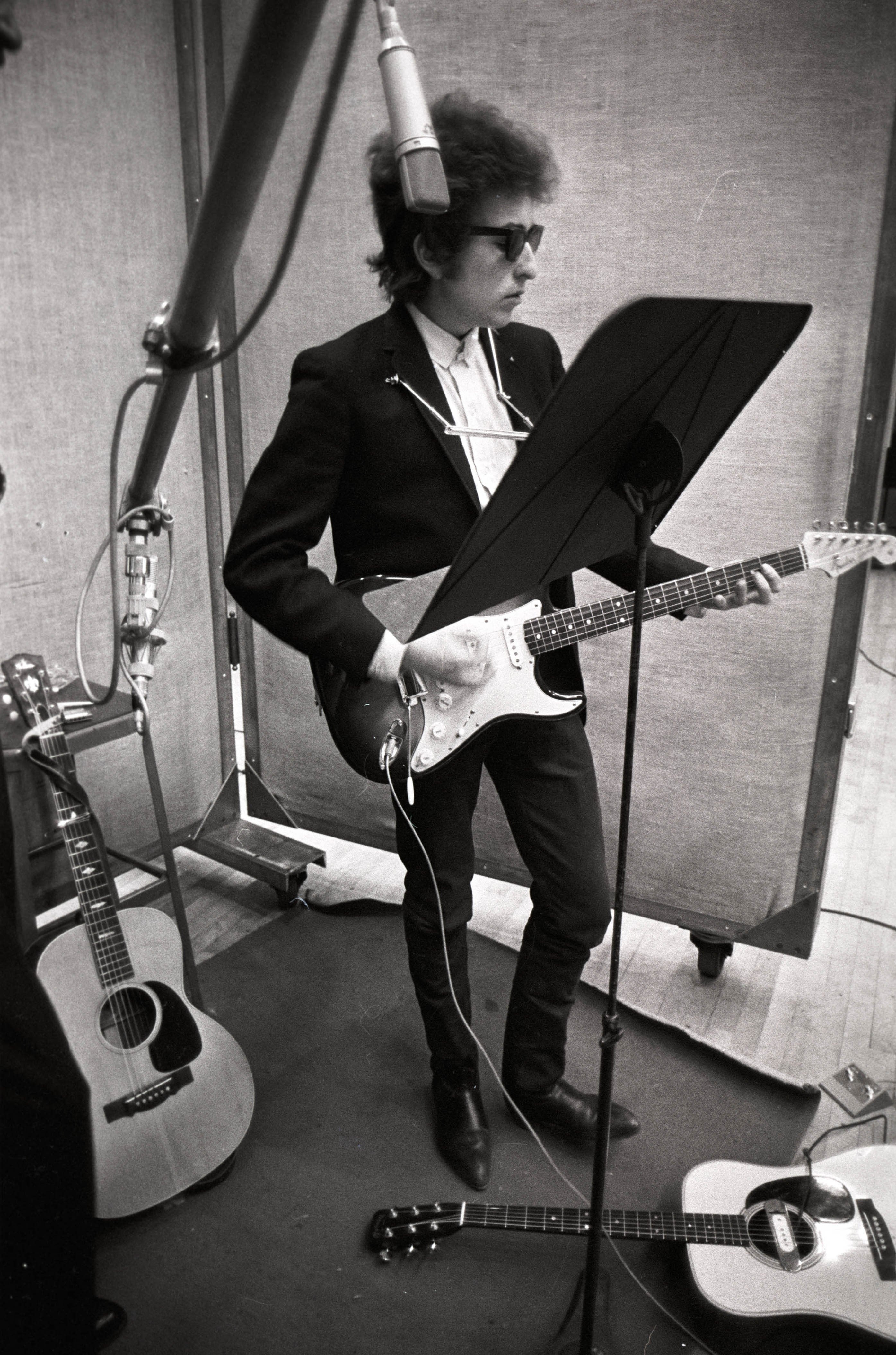

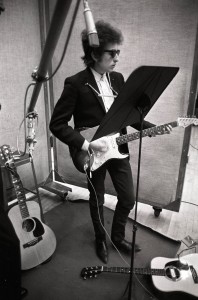

A: It’s the same guy. It’s me photographing Bob Dylan. The first set of photographs I took of him were in 1965 in the recording studio with a Nikon. In color I used a Hasebland camera.

“I had asked Al Aronowitz who was in my studio who was talking to a disc jockey that I knew and I was probably photographing somebody. My ear heard them say, ‘Dylan, I saw him yesterday. I’m quite friendly with him.’

“I said, ‘Hey. The next time you see him tell him I’d like to photograph him.’ The next day I got a call from his wife Sara. Who I knew before she even knew him. She was the one who kept telling me about Bob Dylan. Sara said to Bobby that I would like to photograph you’ and he said ‘OK.’ And I replied, ‘I’d love too.’ She gave me the address where they were recording ‘Highway 61 Revisited’

“Next day I went over and was welcomed. He even let me hear some of the sides they were doing and comment on it. I must say I was a little intimidated at first but they really made me quite at home.

Q: Was the work presented that potent to you at the time of the sessions? You had shot a lot of people for Vogue and LIFE previously.

A: I think it was Dylan. I had photographed a lot of people. The Duke of Windsor when he was once the King of England. I don’t have to be intimated by anybody.

“But, you know, when you come across a talent like Dylan…I didn’t catch on to him at the beginning. I was listening to him and it was Sara and Nico from the Velvet Underground they kept yelling, ‘Genius.’ I was very impressed what I heard and what he was doing. He was funny. We used to go to my club, Ondine’s. I was a stock holder, sit at the bar and hang out.

Q: It seems Dylan really knew the power of imagery and photographs in the media.

A: You’re right. Because the first shoot was during the Highway 61 recording studio and, of course, that’s his kingdom. He could do anything he wants because he’s comfortable there. He was also comfortable around me because of Sara and Al. I got the photographs in and wanted them to like them and they did. And that’s when I wanted to get him into my studio where I had more control. And once he came to my studio, there was nothing he’d say no to, basically. I’d find a prop that I might have used in a previous photograph, I’d give it to him and he’d do something with it. He was just very cooperative and he felt at home too. My studios and film sets are always that way. I want people to feel comfortable and I want them to do something usually a little bit different from what they do in real life. I make them comfortable and they do it.

Q: Your book Thin Wild Mercury Touching Dylan’s Edge is terrific. What was it like assembling the package and viewing the images like 40 years after they were done?

A: What struck me during re-visiting the experience was that it was quite good. I photographed Bob’s first son with Sara. I photographed a lot of things that were very personal. I think what struck me most was when I put the book together I put all my Dylan stuff at the beginning and the interview what I did at the end. I went into my childhood, getting into photography. It worked beautifully.

Harvey Kubernik has been a music journalist for over 44 years and is the author of 8 books.

During 2014, Harvey’s Kubernik’s Turn Up the Radio! Rock, Pop, and Roll in Los Angeles 1956–1972 was published by Santa Monica Press.

In September 2014, Palazzo Editions packaged Leonard Cohen: Everybody Knows, a coffee—table—size volume written by Kubernik, currently published in six foreign languages. BackBeat/Hal Leonard Books in the United States.

Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik wrote the text for photographer Guy Webster’s first book for Insight Editions published in November 2014. Big Shots: Rock Legends & Hollywood Icons: Through the Lens of Guy Webster. Introduction by Brian Wilson).

In November of 2015, Back/Beat/Hal Leonard published Harvey’s book on Neil Young, Heart of Gold.