World Premiere in San Diego California August 2019;

Gold Star/Stan Ross Documentary In Production

By Harvey Kubernik © 2019

33 1/3 – House of Dreams tells the story of the legendary and landmark Gold Star Recording Studios in Hollywood and its co-founder, lead  engineer and hit maker Stan Ross. Gold Star was the birthplace of some of the greatest pop and rock hits of all time over a 33 1/3 year period.

engineer and hit maker Stan Ross. Gold Star was the birthplace of some of the greatest pop and rock hits of all time over a 33 1/3 year period.

Gold Star garnered more Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) Songs of The Century and Grammy Hall of Fame winners than any other independent studio in America. The Gold Star Recording studio was built in 1950 and lasted until 1984 at 6252 Santa Monica Blvd until a fire destroyed the property in March 1984.

Johnny Mercer, Bobby Troup, Sammy Fain, Eddie Cochran, Jack Nitzsche, Herb Alpert & the Tijuana Brass, Buffalo Springfield, Neil Young, Phil Spector, Brian Wilson with The Beach Boys, Marty Balin, Leonard Cohen, The Who, Ike & Tina Turner, Jackie DeShannon, The Band, Hugh Masekela, Iron Butterfly, Sonny & Cher, Bob Dylan, Allen Ginsberg, Arthur Lee, Jimi Hendrix, The Association and The Ramones along with many other recording artists utilized the famed location.

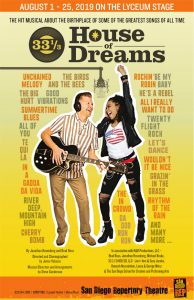

In June 2019, the San Diego Repertory Theatre (San Diego REP) announced that they will be partnering with the San Diego School of Creative and Performing Arts (SDSCPA) and R & R Productions, LLC for the world premiere musical 33 1/3 – House of Dreams. Written by local San Diegans Jonathan Rosenberg and Brad Ross, with additional contributions by Steve Gunderson and Javier Velasco, the debut production chronicles the success of Gold Star Recording Studios through the history of rock ‘n’ roll.

Imagine a story featuring the music of a young Phil Spector and his Wall of Sound, The Beach Boys, Eddie Cochran, Sonny and Cher, Ike & Tina Turner, The Righteous Brothers, Ritchie Valens and many, many more.

The show’s 30-song playlist includes rock ‘n’ roll classics such as “Summertime Blues,” “La Bamba,” “Good Vibrations,” “Be My Baby,” “Unchained Melody,” “Wouldn’t It Be Nice” “In A Gadda Da Vida,” “Tequila,” “Be My Baby,” “Da Doo Run Run,” River Deep, Mountain High,” “Let’s Dance,” “Rhythm of the Rain,” “He’s a Rebel,” “The In Crowd,” “Grazin’ In The Grass” and “Rockin’ Robin.”

The production will feature direction and choreography by Javier Velasco with musical direction and arrangements by Steve Gunderson. 33 1/3 – House of Dreams will run August 1 – 25, 2019, at San Diego REP’s Lyceum Stage Theatre, with previews August 1 – 6, and press opening on Wednesday, August 7 at 7:00 p.m.

Website: www.sdrep.org

“The creation of 33 1/3 – House of Dreams is the culmination of efforts to share the story of what happened within the walls of Gold Star Recording Studios,” shared writers and co-creators Jonathan Rosenberg and Brad Ross in the San Diego Theatre Repertory’s news release.

“Our musical is a way for us to honor the hit music and achievements through one of its co-owners, Stan Ross. He was the personality, lead engineer and mentor at Gold Star. His creative pioneering along with his partner’s technical knowledge and studio design led them to develop Phil Spector’s famous Wall of Sound productions. Stan’s story is our story, and is still relevant today.”

Brad Ross is the co-writer of 33 1/3 – House of Dreams and a practicing dentist in San Diego, California. Raised in Burbank, California, the story of 33 1/3 – House of Dreams centers around his father Stan Ross – co-owner and engineer at Gold Star Recording Studios in Hollywood who died on March 11, 2011 following an operation to correct an abdominal aneurysm at age 82.

Brad participated in interviewing many artists, producers, songwriters, musicians, arrangers, music historians, and ex-employees who recorded at Gold Star. His passion for sharing the stories and music of Gold Star inspired Brad to collaborate with his patient, Jonathan Rosenberg to develop this project. Brad is a graduate of Oregon State University and USC School of Dentistry.

“After the death of my father in 2011, I took on the role of creating a production that would tell his life story,” explained Ross. “As a producer and co-writer, I have spent the last 4 years researching and conducting video interviews with artists, songwriters, producers, arrangers, musicians and former employees that were involved in any aspect of Gold Star’s existence as a mecca for the music industry from 1950-1984.

“These interviews have advanced both our projects: a music documentary and a theatrical musical stage play.

“In the play, we follow the path of Stan and his partner David Gold reflecting on the creative events and significant moments that allowed the studio to become one of the most successful independent recording studios in the world. Their creativity was recognized and promoted by Phil Spector in his Wall of Sound productions. He selected Gold Star due to its famous echo chamber and engineering techniques that allowed his unique production style to flourish.

“Gold Star was a place where any nationality, race, and faith could feel welcome to record and perform their music in a nurturing and welcome environment.

“The play is being directed by San Diego’s Javier Velasco with music direction by Steve Gunderson, both well-known creative resources in the San Diego community.

“Jonathan is a member of The Dramatist organization and is the lead writer/researcher/interviewer on the projects. My role in addition to writing has been to develop relationships with the individuals that were part of Gold Star’s history and to oversee business aspects of R & R Productions, LLC.”

Jonathan Rosenberg is a native of The Bronx, for 30 plus years Rosenberg, in addition to being a psychologist and teacher, has worked as an entertainment writer, radio personality and a lead singer/songwriter. In 2014, he turned his attention to playwriting and broke attendance records at the San Diego Fringe Festival for his musical, Long Way to Midnight.

In the coming months, Jonathan will have two World Premiere musicals opening: 33 1/3 – House of Dreams, and Americano (Phoenix Theatre in Arizona). Jonathan received his bachelor’s from City College in New York, his Master’s from the University of Michigan, and his Doctorate from Alliant University in San Diego.

“What amazed me the most about this project was the reverence the music community still has for Stan Ross,” exclaimed Rosenberg. “The fact that Brad was Stan’s son opened almost every door we knocked on. Brian Wilson, Bill Medley, Herb Alpert, Richie Furay, Mike Curb, and the Wrecking Crew musicians spent time with us recollecting their many great Gold Star memories.

“At that point, we realized that this was a story that has yet to be told. People don’t think of Gold Star Recording Studios in the same way they think of Sun Studios, Motown, or Abbey Road. That’s all going to change after they see 33 1/3 – House of Dreams.”

“It’s an amazing story and should be told for the younger generation to follow,” touted the late drummer/percussionist Hal Blaine in 2013.

Former Gold Star clients were Bobby Darin, Herb Alpert & the Tijuana Brass, Sonny & Cher, Buffalo Springfield, Neil Young, Jack Nitzsche, Phil Spector, Shel Talmy, Brian Wilson with The Beach Boys, Kim Fowley, Leonard Cohen, Barry White, The Association, The Cascades, Iron Butterfly, The Crystals, The Ronettes, Darlene Love, Cher, Don Ralke, Eddie Cochran, Jerry Capehart, Jackie DeShannon, Bob Dylan, Clydie King, David Briggs, Don Peake, Art Garfunkel, The Contrasts, Dick Dale, Johnny Crawford, Johnny Burnette, Thee Midniters, The Sunrays, The Rose Garden, Mark and the Escorts, Jon & The Nightriders, Ike & Tina Turner, Tim Hardin, The Beau Brummels, The Murmaids, Led Zeppelin, Ronald Reagan, Hoyt Axton, The Knack, Robin Ward, George Carlin and Jack Burns, Don Was, Duane Eddy, The Dillards, Maurice Gibb, The Chipmunks, Righteous Brothers, The Sonics, Margie Rayburn, Marlon Brando, The Band, The Cake, The Runaways, The Go-Gos, The Ramones, The Seeds, The Monkees, The MFQ, The Turtles, The Wigs, Oscar Moore, Gerry Mulligan, Mundell Lowe, Chet Baker, Louis Bellson, and The Hi-Los.

During 1962 before Marty Balin founded Jefferson Airplane, he and arranger Jimmie Haskell waxed “I Specialize in Love” at the facility. In 1963, Noel Scott Engel, later known as revered UK musical icon Scott Walker, was hired for menial tasks and cut instrumental music and where Jimi Hendrix and Arthur Lee in 1964 teamed on Rosa Lee Brooks’ “My Diary” 45 RPM engineered by Doc Siegel.

Dobie Gray’s “The In Crowd,” arranged by Al De Lory, Chris Montez’s “Let’s Dance” and Jackie DeShannon’s Laurel Canyon were done on the premises.

The Gold Star environment yielded Hugh Masekela’s “Grazin’ in the Grass, arranger Gene Page’s Blakula soundtrack and Star Trek’s William Shatner reciting “Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds.”

Kit Lambert produced “Call Me Lightning” by The Who at Gold Star and mixed their “I Can See For Miles.” Also birthed at this mystical spot Charles Wright & The Watts 103rd Street Rhythm Band’s “Express Yourself,” Shelby Flint’s “Angel On My Shoulder” and “Endless Sleep” by Jody Reynolds.

Cher’s first solo hit single, “All I Really Want To Do,” written by Bob Dylan, originated from Gold Star, alongside her albums with Sony Bono, as well as Sonny’s own outing “Laugh At Me.”

In my 2009 book, Canyon of Dreams: The Magic and the Music of Laurel Canyon, the multi-instrumentalist Randy Sterling described the studio scenario around Cher’s “All I Really Want To Do,” even playing a pivotal role in ensuring it got on tape in the first place.

“We had finished the basic track and, in the hallway that led out to the back alley at Gold Star, Cher was standing there alone with her hands on her hips. She was about to record to record her lead vocal and was alone. She turned around and almost had tears in her eyes. ‘Oh Randy, I just don’t know if I can do this.’

“I gave Cher a big hug and said. ‘Honey, you’re the best. This is nothing. This is easy and it’s your song. And it’s gonna be a big hit.’ I gave her a pep talk. ‘You haven’t sung it yet and I know it’s gonna be a big hit. Get in there and do what you do and it will be fine.’

“She walked back into the studio, did it, and knocked it out of the ball park in one take. When we were doing it I knew it was good. I hung out with Sonny & Cher a lot when they were based out of Laurel Canyon.”

“Gold Star felt and sounded different than any other L.A. studio,” mused The Turtles’ Howard Kaylan, who recorded “The Story of Rock & Roll” pop gem and other wonderful tunes like “Eleanor” there in addition to their revolutionary The Battle of the Bands produced by Chip Douglas.

“You could literally smell the tubes inside the mixing board as they heated up. There was a richness to the sound that Western and United, our usual studios, never had. Those two rooms sounded ‘clean’ while Gold Star felt fat and funky. Perhaps we were all reading too much of the Spector legacy into the room, but I don’t think so. Our recordings from Gold Star always just sounded better to me. I miss that room.”

At this temple of sound Don & Dewey’s “Jungle Hop” introduced the electronically distorted guitar while Phil Spector’s production of “Zip A Dee Do Dah” by Bob B. Soxx & The Blue Jeans was the first distorted lead guitar on a hit record.

Gold Star also developed phasing, DT (Double-tracking) and flanging techniques. Gold, Ross and engineer Larry Levine integrated the concept of phase-shifting or “phasing” a sweeping effect that incorporated electronic music on their hit disc “The Big Hurt” by the vocalist Toni Fisher.

In 2015, the legacy of Gold Star was depicted in a documentary, The Wrecking Crew by filmmaker Denny Tedesco, son of guitarist and studio musician, Tommy Tedesco.

This decade, Brian Wilson, Herb Alpert, Richie Furay, Mike Curb, Chris Montez, Kim Fowley, Steven Van Zandt, Marky Ramone, Nino Tempo, Bill Medley, Richard Sherman, Donna Loren, Jon Blair, Brian Stone, Carol Connors, Mark Guerrero, Lyle Ritz, Carol Kaye, Johnette Napolitano, Don Randi, David Kessel, Don Peake, Perry Botkin , Jimmie Haskell, Artie Butler, Sheryl Paris, Stan Ross, Vera Ross, Lyn Levine, Lou Mattazera, Fanita James, Don Snyder, Neil Norman, Leo Eiffert and myself were filmed for a documentary now in production about Gold Star and co-owner/engineer Stan Ross directed and produced by Jonathan Rosenberg and Stan’s son, Brad Ross.

In every book and story about the life of Phil Spector, Stan Ross is mentioned along with Dave Gold, and Larry Levine. They collectively toiled for years in Gold Star, made overt and subtle sound design contributions to Phil Spector’s studio undertakings while jointly constructing the “Wall of Sound.”

Gold Star and Spector were a special force of destination. The alchemy of geography, Ross, Gold and Levine’s technical acumen combined with Spector’s stylistic confidence

Dave Gold hailed from the Boyle Heights section of East Los Angeles California.

Ross, born in Brooklyn, New York in 1928, moved with his parents to Los Angeles at age 15. Stan then enrolled at Los Angeles’ Fairfax High and graduated in 1946. Stan wrote a music column in the Fairfax Colonial Gazette called Musical Downbeat and his reporter scoops were bannered Off the Record.

When he was a teenager, Ross studied recording from a pioneer of modern disc recording Bert B. Gottschalk. Stan worked at his Electro-Vox studio for four years as an engineer and was responsible for one hit record, “Deck of Cards” by T. Texas Tyler.

“Gold Star used to be a dentist’s office,” Stan Ross reminded me in a 2001 interview we conducted. “We started pulling teeth a different way.”

Gold Star was built in 1950 and lasted until 1984 at 6252 Santa Monica Blvd until a fire destroyed the property in March 1984.

“Gold Star was built for the songwriters. They were fun, wonderful people to be around: Jimmy Van Heusen, Bobby Troup, Bob and Richard Sherman, Sammy Fain, Sonny Burke, Don Robertson, Johnny Mercer, Jimmy McHugh, Frank Loesser, Dimitri Tiomkin. We did song demos, voice-over work, radio and TV jingles,” reminisced Ross.

“I loved music, and I was a record buyer, and I know what I liked. If I’m going to buy a record, I want it to sound like this. So I made everything I got involved with like something I would buy.

“Our studio echo chamber gave it the wall of sound feel. Dave (Gold) built the equipment and echo chamber and personally hand-crafted the acoustical wall coating. We had so much fun with that echo chamber; it never sounded the same way twice. Gold Star brought a feeling, an emotional feeling.

“The soundboard was all tubes. And when you have tubes, you have expansion and it doesn’t distort so easy. We kept tubes on longer than anyone else. Because we understood that when a kick drum kicks into a tube it’s not gonna distort. A tube can expand.

“The microphones with tubes were better than the ones without the tubes because if you don’t have a tube and you hit heavy, suddenly it breaks ups. But when you have a tube it’s warm and emotional. It gets bigger and it expands. It allows for the impulse,” underscored Ross.

“Gold Star brought a feeling, an emotional feeling. I’ve been in other studios that were ‘too hot,’ ‘too lively.’ Some that sounded like cardboard boxes. ‘Too dead.’

“Gold Star had enough echo that if you snapped your fingers, or clapped your hands, you could actually hear it. So if that’s the way your hands clapped, then your drum sound would be the same kind of feel. Our echo chamber gave it the ‘Wall of Sound’ feel. It was smaller than most people knew.”

Stan was behind the console for Phil Spector on his 1958 Teddy Bears’ recording, “To Know Him Is to Love Him” and subsequent Spector bookings at Gold Star 1962-1966.

The history and mystery of Gold Star and previous clients in the mid-fifties were not lost on Phil when he knocked on their magical entry door.

“Phil followed in a studio tradition,” reinforced Stan. “We used Studio A. Eddie Cochran used our Studio B. Down the stairs by the parking lot. I cut ‘Tequila’ there by The Champs.

“I did a whole lot of Eddie Cochran’s records including ‘Summertime Blues,’ ‘20 Flight Rock,’ and ‘C’mon Everybody.’ The vocal of Ritchie Valens’ ‘Oh Donna’ was recorded at Gold Star. The backing track was done up the street at Bob Keene’s studio who owned Del-Fi Records.

“Phil served the song. He was as concerned as they were about the song — one of the reasons Phil’s songs have durability and are copied,” observed Ross. “He worked for the tape. He knew what he could get away with and what he couldn’t and he appreciated whatever suggestions Larry Levine or myself would give him. He never closed his mind to anything. He was always open-minded. He was very emotional about his records.

“I thought things we did with The Paris Sisters were terrific. I saw a lot of growth with Phil very early. The day he first walked in I explained to him the studio policy of buying time by the hour and a role of tape I had to be firm ‘cause I didn’t want 20 more ‘Phil Spectors’ coming in,” laughed Ross.

“Phil appreciated mono. But we did back up with multi-track. So, if he wanted to go back to the four-track, he would. He never did, ‘cause if he didn’t hear it, it wasn’t right.

“When it came to multi-track you could put everything on mono. The bass drum, the guitars and keep it. Once you have it on mono, it never changes. It will be the same on Wednesday then the previous Tuesday, the same sound. So when you do transfer from one track to four tracks, it’s OK. And to that you can add voices, never losing the quality of the bass drum track, because it’s been transferred, it hasn’t been disturbed.

“You took the mono and transferred it to track one of a four track. Tracks two, three and four are for voices and guitar fills. You follow? Everything is a fresh generation. It saves you from having to overdub four generations. You have less highs and less sibilance. And, we didn’t use pop filters and wind screens, we got mouth noises. Isn’t that life?”

In the mid-seventies I published a couple of articles on Phil Spector in Melody Maker. They were culled from a series of interviews in Hollywood at the Sherwood Oaks Experimental College, inside his Beverly Hills mansion, and around Gold Star studio visits where he was producing Dion and a new singer, Jerri Bo Keno.

“I was a young aspiring guitar player,” recollected Phil. “I played on some of Big Mama Thornton’s records. I always wanted to be a producer. There’s an old story I’ve told before. ‘OK. Let’s play baseball. You be the pitcher. You’re the catcher, and you’re the batter. Spector, you be the producer.’ I was always into that.

“Dave Bartholomew, Sam Phillips. I wanted to know about the people behind the scenes, the guy who played the solo on ‘Rock Around The Clock.’ The tape echo sound. These things interested me. They were exciting.

“I played on records before I made ‘em. I worked with Leiber and Stoller. We made a lot of records, played on sessions by the Drifters, the guitar on ‘On Broadway,’ ‘Lavender Blue.’

“‘To Know Him Is to Love Him’ the first one. That was the one I was gonna kick ass with. I was part of the Teddy Bears group. We did The Perry Como Show.

“I record in a strange way. I haven’t changed. I go from the basic track and put it onto 24. Then I have one track and 23 open. That’s the difference between having 24 filled or 19 filled, which means I can get 23 string players and overdub them 10 times and have 200 strings. Then I put them on one track. I record basic tracks and then put it all onto one track or maybe two.

“I like to have all the musicians there at once. I’ve used Barney Kessel all the time for the last ten years. Terry Gibbs on vibes…Everybody. The better the talent is around you, the better the people you have working with you, the more concerned., the better you’re gonna come off as a producer, like a teacher in a class.

“The musicians I have never outdo me. I’m not in competition with them. I’m in complete accord with them.

“Then I condense. I put my voices on. Singers are instruments. They are tools to be worked with. You tell me how many names you immediately remember in the cast. 1? 2? It’s the same with Fellini, and that’s what I wanted to do when I directed a recording.

“I always thought I knew what the kids wanted to hear,” confided Phil in his home one sunny afternoon after we split Pink’s Hot Dogs for lunch washed down by four bottles of Orange Crush.

“They were frustrated, uptight. I would say no different from me when I was in school. I had a rebellious attitude. I was for the underdog. I was concerned that they were as misunderstood as I was.”

In a 2019 phone interview from Bogota, Colombia, record producer, author and deejay Andrew Loog Oldham pronounced the Spector and Gold Star impact on him. Oldham was the manager and record producer of the Rolling Stones 1963-1967.

“In late 1958 ‘To Know Him Is to Love Him’ changed my world. I was 14. I’d loved ‘Born to Late,’ ‘Silhouettes’ and ‘Come Softly to Me,’ but this was different.

“This was the sound of one man screaming at and embracing his very own version of the world. And he managed to record that sound. And that sound, that feeling and meaning has managed to survive man going to the moon, doing the moonwalk, giving live aid and being born to run.

“Phil Spector wrote, arranged and produced the record, he was just 17. You know what I mean …He made it with Stan Ross and Gold Star and they changed the sound of music. It would never be the same again…”

“Phil was a pretty good jazz guitarist. May I point out to you [that], if you listen to his recording with the Teddy Bears on ‘To Know Him Is to Love Him,’ when that bridge goes off to the planet Mars and changes key, that’s the stamp of a jazz musician,” reiterated Wrecking Crew guitarist Don Peake, who played with the Everly Brothers from 1962-1964, including a 1963 tour of England when the Rolling Stones and Bo Diddley were opening acts.

On that trek, Keith Richards said in an issue of New Musical Express, “I have picked up as many hints on guitar playing as I can from Don Peake. He really is a fantastic guitarist, and the great thing about him is that he is always ready to show me a few tricks.”

During a 2014 email exchange, Andrew Loog Oldham recognized the influence Spector and Gold Star were on his early record productions.

“I heard the record “To Know Him Is to Love Him” in the UK. It made an impact because of the use of room, the usage of tape delay. You knew something was going on, even if you didn’t know what it was.

“Later, after, I’d recorded the Rolling Stones’ ‘Not Fade Away’—or let’s say ‘Little Red Rooster.’ You realized, by recording in similar mono circumstances, in London’s Regent Sound as opposed to Gold Star, or wherever Phil did ‘To Know Him Is to Love Him,’ what the room brought to the game.

“There is a lot of magic to ‘To Know Him Is to Love Him.’ Basically, how can anybody resist those backgrounds? It’s a great part for the public to sing along with and be at one with the song. Maybe one of the things that drew me to the record was that there was a subliminal audio text from Eddie Cochran records. Eddie had already recorded ‘Summertime Blues’ at Gold Star. So we didn’t know, but you do know, man. That’s my memory of it.

“Phil Spector had so many firsts. His ‘To Know Him Is to Love him’ was a fifties garage equal of Les Paul and Mary Ford. His early sixties run with the Crystals and the Ronettes set the audio standard for so many . . . and we are all still humming that standard.”

In 1964 Oldham produced a cover version “To Know Him Is to Love Him” by Cleo Sylvestre with the musical arranger Mike Leander.

During our 2019 talk, Andrew acknowledged, “The reason I did Cleo with The Teddy Bears song was that it seemed an appropriate homage to a piece of vinyl that had so warmed my life as my first non-Stones release. I knew it would not be a hit. That was not the point. It was a mission statement.”

In 1964, Oldham and his Andrew Loog Oldham Orchestra covered Spector-produced and Jack Nitzsche-arranged The Crystals’ “Da Doo Ron Run” with Mick Jagger joining in on vocals.

“Da Doo Ron Ron” is incorporated into the San Diego Repertory Theatre’s repertoire of 33 1/3- House of Dreams.

“As for ‘Da Doo Ron Ron by the Orchestra,” admitted Andrew, “that was done in Mono at Regent Sound aping the Jack Nitzsche version which I would do better, later, with the currently topical version of ‘The Last Time’ by the Orchestra.

“The earlier Jagger vocal’s orchestra version shows us learning on the job. There’s a great moment two minutes of so in where the two overdubbed cellos force the basic track to nearly drop out.”

In 1964 Andrew produced a recording with John Baldwin, (then quickly re-named John Paul Jones, before his Led Zeppelin career) on a re-make of Nitzsche’s “Baja,” the flip side of Jack’s instrumental anthem, “The Lonely Surfer.”

“When I first heard [a white label acetate 45 pressing] ‘You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’’ in Phil’s New York office,” Oldham willingly disclosed to me “before anyone in the world, I thought I might be listening to three records being played at once. I was in turmoil, because, I’d just heard God and felt like throwing in the towel as a producer.”

Larry Levine, Ross’ cousin, who also attended Fairfax High School, was one of the house engineers at Gold Star and a crucial component in Spector’s “Wall of Sound” audio endeavors.

Levine won a 1966 Grammy Award for Best Engineered Recording-Non Classical, for his work on “A Taste of Honey” performed by Herb Alpert & the Tijuana Brass.

Larry engineered albums for Eddie Cochran, The Beach Boys, Sonny and Cher, Herb Alpert & the Tijuana Brass, The Carpenters, Dr. John, and with Spector in the late 70s albums by Leonard Cohen and The Ramones’ End Of The Century, with Boris Menart and assisted by Bruce Gold.

“As a matter of fact,” mentioned Levine in a 2002 interview, “Phil once said to me the bane of his recording existence was the drum sound. A lot of people attribute to echo to what Phil was doing. The echo enhanced the melding of the ‘Wall of Sound,’ but it didn’t create it. Within the room itself, all of this was happening and the echo was glue that kept it together,” expressed Larry, who passed away in 2008.

“As far as the room sound and the drum sound went, because the rooms were small, with low ceilings, the drum sound, unlike other studios with isolation, your drums sounded the way you wanted them to sound. They would change accordingly to whatever leakage was involved.

“I used to have a theory [that] part of the reason we took so long in actually recording the songs was that Phil needed to tire out the musicians—[until] they weren’t playing as individuals, but would meld into the sound that Phil had in his head.

“The best producers are people who know what they want and know how to communicate so that all of us can strive towards their goal, while the producer is still amenable to something else that may happen along the way. In my career, I’ve worked with three great producers—Phil Spector, Herb Alpert, and Brian Wilson.”

“The man [Phil Spector] is my hero,” Brian Wilson told me in a 1997 interview for Melody Maker. “He gave rock ‘n’ roll just what it needed at the time and obviously influenced us a lot. His productions…they’re so large and emotional…Powerful…the Christmas album is still one of my favorites. We’ve done a lot of Phil’s songs: ‘I Can Hear Music,’ ‘Just Once in My Life,’ ‘There’s No Other Like My Baby,’ ‘Chapel Of Love’… I used to go to his sessions and watch him record. I learned a lot…

“Let me tell you a story,” Brian Wilson divulged in a 2007 Pet Sounds 40th Anniversary tour program interview we had. “I went to Gold Star and asked Larry Levine, the engineer, ‘What is the secret of the Phil Spector echo trip?’ And Larry replied, ‘Well, we have two echo chambers under the parking lot. Phil uses both the chambers at the same time.’ So I tried that myself and it worked.

“I also wanted to know from Larry what Phil Spector did with his basses. Larry said, ‘Phil uses a standup and a Fender both at the same time. And the Fender guy used a pick.’

“So I tried it out at my session and it worked great! You also get a thicker sound putting the two basses together. I start with drums, bass, guitar and keyboards. Then we overdub the horns and the background voices.

“Hal Blaine is the greatest drummer I ever worked with.”

Wilson was a regular Gold Star visitor and customer for years. Brian produced The Beach Boys’ “Do You Wanna Dance,” “I Just Wasn’t Made For These Times” that featured the initial usage of Therimin on a pop recording, “Wouldn’t It Be Nice,” and the original version of “Heroes & Villains.” A take on “Cabin/Essence” earmarked for Smile was attempted. Father Murry Wilson did his The Many Moods of Murry Wilson LP there. “Deirdre” and “Slip on Through” on the Beach Boys’ Sunflower, were taped in the historic setting.

“The Wrecking Crew could lock in with anybody,” affirmed Hal Blaine during a 2002 interview. “Our job was making hit records and we loved it. The thing that I had in the early days was Rick Faucher, my drum tech.

“I had Rick go out and buy the biggest beach umbrella he could find and we put that on a boom stand where once I was on the drums, and we sawed it off at the pole. We could bring that over and down around my drums to cover me so that we could get a little less leakage anywhere.

“We were doing a job. We used to say: TTMAR. Take the money and run. Nobody knew how long it would last.”

Don Randi played piano, keyboards, and organ on every Spector-produced/Jack Nitzsche- arranged activity at Gold Star since 1962. In addition, Randi can be heard on the Beach Boys’ album Pet Sounds, Buffalo Springfield Again, Love’s Forever Changes and The ‘68 Elvis Presley Comeback Special. Randi’s resume displays The Birds, The Bees & The Monkees, Tim Buckley’s Goodbye & Hello and Frank and Nancy Sinatra.

“Gold Star was an incredible place since the first time I ever worked there,” stressed Don.

“It was friendly. And they always had a good staff there that was friendly. Between Dave Gold, Stan Ross and Larry Levine, and Doc Siegel, it was great and fun. I worked a lot with Stan and Larry. Doc Siegel got destined to do the ‘B’ sides for Phil Spector.

“Everybody playing parts and a lot of time duplication. Like on the pianos, you would have one guy doing a thing on the high end of the piano, somebody in the middle, and Phil would want the different sounds of a concert grand, and an upright, electric or a Wurlitzer. So he liked to have the spread of the different tonality. That was Phil. He understood tonality very well. And at Gold Star it was magic because of all those harmonics rising were part of the wall of sound.

“The studio can make a difference in the sound of a record. At Gold Star it was the echo chamber. Like, when someone talks about a guy being a ‘natural baseball player.’ Gold Star was a natural studio. It just blended and worked. When you went to Gold Star you just knew you were making a hit record. Jack Nitzsche was a good translator for Phil.

“As far as the music recorded and documented in Gold Star, it was because musically and lyrically and the composition and note part was brilliant. There were always great songs. The songs always told a story. The songs in themselves were films. And, especially in Phil’s case, he knew how to write them and how to produce them. And in Brian Wilson’s case, Brian always knew where he was going with it. He may have not known at the beginning, but after a while he had an idea and he developed it. We were there to help him develop it,” suggested Don.

Randi, who headed the house band at Sherry’s cocktail bar on Sunset Boulevard from 1957-1970, listed the Wrecking Crew’s culinary habits and their favorite watering holes after their work at Gold Star was finished.

“Jack Nitzsche and I would go out to places like the Gaiety Delicatessen. Once in a while Harry Nilsson would come to our table. He was still working at the Crocker Citizen bank as a teller or had a job there. He might have made a record then. Myself, Jack, Neil [Young] and Denny Bruce also liked to eat at the House of Pancakes on La Cienega.

“We loved Musso & Frank’s Grill on Hollywood Boulevard and Johnny’s Steak House. That was my savior. I didn’t have a fuckin dime and I could go and have a three dollar meal in there with a Rib Eye. Can’t forget The Brown Derby. We went to Aldo’s, great hamburgers. Sonny & Cher dug that place, Canter’s Delicatessen, and once in a while, a coffee shop called Huff’s. Taco-rama, and Pink’s Hot Dogs on La Brea. Another tasty stop was The Dog House on Hollywood where you sat on stools right on the street.

“There was Young China, two doors down from radio station KFWB for fantastic Chinese on Hollywood Boulevard. The best Won Ton soup. The Italian restaurant Miceli’s was on Las Palmas. The record company promo men all went to an Italian spot named Martoni’s.

“Dennis Wilson loved Ah Fong’s restaurant, delicious Chinese-American food. Gene Norman owned the Marquis restaurant on Sunset Strip, along with his Crescendo and Interlude clubs. I liked the Villa Capri. Phil Spector and I went to The Cock ‘n Bull. The trout was incredible.

“Label owners like Norman Granz at Verve Records enjoyed the Pacific Dining Car. Barney Kessel and his wife BJ Baker requested their New York steaks cooked medium at Diamond Jim’s in Hollywood.

“As you well know, we all went to the Hollywood Ranch Market. Are you kidding? The tater tots and the chicken gizzards! In the late fifties they had a donut machine there! [Laughs]. I saw Lucille Ball one late night. In a full fur mink coat! She gave me the biggest smile. Rock bands, hookers, actors and hippies were at the counter, especially when there was a show at The Kaleidoscope or Hollywood Palladium.

“They just closed Hamburger Hamlet on Sunset Boulevard! What the fuck is going on?”

In a 1988 interview for Goldmine magazine, I asked Jack Nitzsche how the “Wall of Sound” was formed.

“It happened over a period of time. I don’t know who coined the term. The sound just got bigger and bigger. One time we cut the Crystals’ ‘Little Girl.’ Sonny Bono was the percussionist on the date. He came into the booth, and said it had more echo than usual, and it wouldn’t get played on the radio. The echo was turned way up high. Phil once said during a session, ‘What’s too much echo? What does that mean?’ Phil was smart enough to say, ‘Wait a minute listen to this.’ If you notice, there’s more echo on each song we cut. It hadn’t been done like this before. People on the business side, the promotional side of the record industry, felt it was different. He didn’t listen to them,

“There were four echo chambers, and I remember engineer Stan Ross, who was co-owner with Dave Gold, telling us many times that the echo chambers were acoustically and geometrically designed to get the right amount of balance and reverb. That added to the impact of Phil’s recordings. I loved the echo. It’s like garlic. You can’t get too much.

“The musicians played at once. Before that, I was working with compact rhythm sections and three or four players. This was groundbreaking for me.

“On my sessions from 1960- to 1962 I booked Leon Russell, Harold Battiste, Earl Palmer, Don Randi, Hal Blaine, and Glen Campbell . . . a lot of the players came out of my phone book. Phil [Spector] knew Barney Kessel. He had taken guitar lessons from him.

“Hal Blaine . . . I liked his work, but sometimes felt he overplayed. That’s just the way he plays. A lot of fills, as it turned out, Phil and the people loved the breaks Hal took, especially at the end of the tunes, the fades. Hal had a big kit. I liked the fills.”

“The vocals would last all night. Background groups doubling and tripling so it would sound like two or three dozen voices. Phil would spend a lot of time with the singers. I would split and he’d still be working on lines with the singers. The rhythm section and the horns were done together. Vocals and string parts were overdubbed later. We did most of the sessions at Gold Star studios in Hollywood. I loved the rooms, but it was always too small for all the people. Phil was on his game all the time.

“‘Then He Kissed Me’ is my favorite Crystals record. Listen to the percussion! Castanets and all. We had some room to experiment and make records sound different. Phil would go into the percussion kit and say, ‘this song needs castanets.’ Everything blended so well.

‘“Be My Baby.’ Ronnie Spector’s voice. Wow! I was amazed at her vibrato. It got bigger and bigger with each record. That was her strong point. When that tune was finished, the speakers were turned so high in the booth people had to leave the room. It was loud.

“I arranged the Christmas album. We had a lot of fun. Darlene Love singing ‘Christmas (Baby Please Come Home)’ blew my mind. I got chills. Powerful. She could always sing. Sonny always made everyone laugh. The album never really took off. I think some of that had to do with the world after the Kennedy assassination. It affected the public. No one wanted to celebrate Christmas in December 1963…”

In 1965, Nitzsche took Rolling Stones’ drummer Charlie Watts to a Phil Spector session at Gold Star.

The epic song River Deep, Mountain High,” written by Jeff Barry, Ellie Greenwich and Spector, was initially arranged by Jack Nitzsche and produced by Spector in 1966 on Ike & Tina Turner at Gold Star.

“Phil Spector helped write ‘River Deep, Mountain High’ and said, ‘I’ve got a song for Tina,’” Jack Nitzsche told me in our 1988 interview. “I went over to Phil’s house and went over the arrangement note by note. When Phil played me it on the piano I knew it was a great song.

“We did the rhythm track in two different three-hour sessions. Even during the cutting of the track, when she was putting on a scratch vocal, Tina was singing along as we cut it. Oh, man, she was great, doing a rough, scratch vocal as the musicians really kicked the rhythm section in the ass.”

Brian Wilson, Dennis Hopper, Mick Jagger and Rodney Bingenheimer were in attendance when it was created. The 1966 45 RPM was first released on Spector’s Philles Records label.

In 1975 I interviewed Tina Turner for Melody Maker about this sonic revolution done without auto-tune assistance.

“’River Deep, Mountain High” was a smash in England,” recalled Tina. “The biggest change started happening when we were working around L.A. in 1966 and ran into Phil Spector. He wanted to record me and when we cut ‘River Deep, Mountain High’ Mick Jagger, who was visiting Phil at the time, was in the studio. After hearing the song he wanted us to tour England in 1966 with the Rolling Stones.

“River Deep, Mountain High” only reached number 88 in the U.S. Billboard singles chart, but a number 3 position in the UK market. John Lennon called “River Deep, Mountain High” a “masterpiece.” George Harrison provided a front jacket blurb on the Spector produced Ike & Tina Turner River Deep, Mountain High album: “It is a perfect record from start to finish. You couldn’t improve on it.”

A rendition of “River Deep, Mountain High” is spotlighted in the 33 1/3-House of Dreams theatrical run.

Since 1966, Dobie Gray, Long John Baldry, Harry Nilsson, Deep Purple, Bob Seger System, Annie Lennox, Celine Dion, The Easybeats, Neil Diamond, The Four Tops, Eric Burdon Brian Auger Band, Les McCann and the cast of Glee covered the composition.

As a teenager, Rodney Bingenheimer, now a Sirius XM deejay on Little Steven’s Underground Garage channel was a Gold Star invited guest attending countless Buffalo Springfield, Iron Butterfly, Dr. John, and Sonny & Cher activities at the studio.

Rodney went to Gold Star with Jimi Hendrix when The Cake was doing their debut album, driving down from Monkees’ Peter Tork’s house in the Laurel Canyon region while cruising in Jimi’s powder blue Corvette Sting Ray.

“I loved Gold Star,” trumpeted Bingenheimer. “I played one of the tambourines on Sonny & Cher’s ‘Bang Bang (My Baby Shot Me Down).’ I took my mother Marian to one of their sessions, ‘It’s The Little Things’ on the Good Times album soundtrack. I was later at all the Ramones’ sessions at Gold Star that Phil Spector produced.”

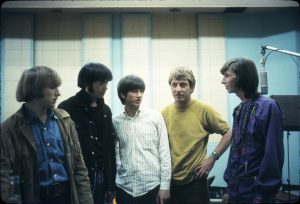

Buffalo Springfield recorded their debut album Buffalo Springfield at Gold Star. Doc Siegel engineered it with Tom May, produced by Charlie Greene and Brian Stone. Buffalo Springfield co-founder Richie Furay is still in awe discussing Gold Star.

“Look, walking into Gold Star studio. I’m a young kid from Ohio,” marveled Furay in a 2001 interview. “And to go in that studio, with all the history, and hear our music coming through those speakers, even though it’s a four-track machine, was bigger than life.”

The Buffalo Springfield Box Set, a 4 CD- collection overseen and assembled by Neil Young in 2001 houses over two dozen band demos recorded at Gold Star under Stan Ross’ supervision.

“I was always impressed by the songwriting abilities of the Buffalos,” offered Ross, “especially Neil Young.

“Neil was really a very personal friend of ours. An appreciative man who never forgot us over the years,” Stan confirmed. “Of all the guys in the group, Neil was the only one who took care of Gold Star, especially Dave Gold. Dave did Neil’s Trans album [and portions of Hawks & Doves.]

“For years Dave did all the mastering at Columbia that Neil did on his albums. He made sure that Dave Gold would do all the lacquer mastering on his albums. No one else. No other place. And if they wanted 15 pressing plants to have masters Neil didn’t want prints made up from one master. He wanted Dave Gold to make 15 separate acetates. And to make sure it was done that way, Dave had to put a number on each one he did that was a code between him and Neil.” [The inner groove of Rust Never Sleeps has the initials “dg” (Dave Gold) inscribed into it].

Over the decades and in my 2014 book, Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop, and Roll in Los Angeles 1956-1972, I interviewed record producer and songwriter Kim Fowley.

“I went to Gold Star my first day in Hollywood, on February 3, 1959,” remembered Fowley, who was a deejay on Little Steven’s Underground Garage channel on Sirius XM satellite radio.

“It was the day Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and the Big Bopper died in an airplane crash in Iowa. I took it upon myself to take their place. I thought that they had passed the baton on to me from beyond. I thought it was my turn to take over,” uttered Kim.

“I met the legendary rockabilly cats Johnny and Dorsey Burnette in 1959. It was during that day in Hollywood at Gold Star, around a Champs recording session I was covering for Dig magazine. I was their campus correspondent and [was] invited to have lunch with Dorsey and Johnny, who were in to play on a long-forgotten B-side of a Champs single.

“Dave Burgess was the producer, who later produced Jerry Fuller. The Burnette Trio was a band. In those days, pre-Beatles, you didn’t sing and play at the same time and write.

“As a visitor to Gold Star, it was the epicenter of teenage rock ’n’ roll recording culture in 1959. If you were in Memphis, Tennessee, you would knock on the door of Sun Records. If you were in Detroit, Michigan, you would knock on the door at Motown. But in 1959, I went to Gold Star. ‘Here I am. Let’s see if I get accepted.’ If you got accepted, you were off and running. You start at the top, and I did. So I will always be grateful.

“It was possibly a double-edged sword for Larry Levine, Stan Ross, and Dave Gold because they figured they would service the emerging rock ’n’ roll community. At that point, the other studios in town had a suit-and-tie vibration. So if some kid had a hundred dollars, he couldn’t even get in there.

“If a kid had a hundred dollars, he could cut a hit record at Gold Star if he saved it or got his friends and family to pitch in with band members. I later worked with their engineer, Doc Siegel, as well. You could go in there and not get intimidated, and you had equal footing with the legendary guys. I saw Eddie Cochran work at Gold Star. He invited me in to watch, listen, and learn,” detailed Kim.

“I produced ‘Nut Rocker’ in 1960 under the name B. Bumble and the Stingers on Transworld Records. I wasn’t allowed to be in the room at the session, so I took a walk. René Hall was on guitar and bass, Al Hazan on piano, and Jesse Sailes was the drummer. I was just the publisher and the writer. I was 22 years old. I had a partnership with Gary Paxton. He was a hillbilly genius who worked with a Hollywood child.

“I scored in 1960 with the Hollywood Argyles’ ‘Alley-Oop’ on Lute Records. [They] were the white Coasters, with a black backing group that no one ever saw. We did ‘Alley-Oop’ at American Recording Studio. The session had keyboardist Gaynel Hodge, a member of the Hollywood Flames who sang with the Platters and co-wrote ‘Earth Angel’ for the Penguins, as well as Harper Cosby, who was on Johnny Otis’s ‘Willie and the Hand Jive,’ [and] drummers Sandy Nelson and Ronnie Selico, who worked with the Olympics and is heard on ‘Big Boy Pete.’ Ronnie was also on the Marathons’ ‘Peanut Butter.’ I learned that you had to have black people with white people on my sessions to get the groove,” Kim revealed.

“We then marched into Gold Star, [which] had mastering facilities, and Stan Ross mastered the record. Stan proclaimed it was going to be a number-one record. He was right.

“In 1963, I was hitchhiking and a budding songwriter, before he was with Screen Gems Music David Gates, picked me up and gave me a ride. We talked; he mentioned he was a songwriter. He had a bass guitar in the back seat. ‘Are you a musician or a songwriter?’

“He wrote songs. I told him who I was. David knew about ‘Alley-Oop’ and ‘Nutrocker.’ We went into my house and he played me ‘Popsicles and Icicles,’ and I said, ‘Hit record!’

“I found a group to do it—the Murmaids. Stan Ross was the engineer. In 1964, The Beatles knocked it out of the number-one slot in Cash Box with ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand,’” lamented Fowley

“At Gold Star Studios, one day I ran into Brian Wilson and he asked me who the Murmaids were. I asked him, ‘What is the basis of your songwriting?’ And Brian said, ‘Well, school is nine months a year and the summer holidays are three months, and you write about that and getting in trouble with your parents.’

“I had two number one records out of Gold Star. I liked the room and the echo chambers, and there were good vibes. It was a magical scenario on many levels. I was a member of the Musicians Union Local 47 located on Vine a couple of blocks from Gold Star. I did various recordings with the Wrecking Crew.

“Phil Spector was The Pope and Gold Star was his Sistine Chapel,” Kim summarized.

Multi-instrumentalist David Kessel is currently CEO of Cave Hollywood. www.cavehollywood.com. He is also a member of the band Willapa.

David is the son of influential jazz guitarist and record producer, Barney Kessel, who can be heard on dozens of jazz, pop and rock ’n’ roll recordings and was a member of the Wrecking Crew.

“I knew my dad as a record producer (Fred Astaire, Audrey Hepburn, Ricky Nelson), not just a guitarist,” reflected Kessel.

David’s stepmother B.J. Baker was also a pivotal architect of classic seminal pop and rock records from the late 1950s through the 1980s and considered one of the top background singers and vocal contractors of her era collaborating with Elvis Presley, The Crystals, Frank Sinatra, Jackie Wilson, Lloyd Price, Brian Hyland, Bobby Vee, Timi Yuro, and Sam Cooke. “She taught me a lot about how vocals should be recorded,” emphasized Kessel.

As a teenager growing up in Southern California, David, along with older brother Dan attended recording dates of The Beach Boys, Phil Spector, Quincy Jones, and Sonny & Cher.

“Phil taught me how to take charge of my vision, and how to take responsibility for achieving that vision,” underlined David, who along with his brother Dan produced a surf version of “To Know Him Is to Love Him” by the Wigs engineered by Stan Ross.

“I grew up going to Phil Spector and Sonny & Cher sessions at Gold Star Studios in Hollywood. My dad Barney would bring me and my brother Dan to the studio. It really was kind of normal progression, which was not on the plan at the time, that we became the only 2nd generation Wrecking Crew members.

“In the seventies we played regularly on records for Phil at Gold Star, from being on Dion, Darlene Love, Cher and Harry Nilsson, Leonard Cohen and the Ramones’ End of the Century there, and doing our own projects.

“The vibe was the best from all the studios in town. Gold Star always felt like home. It captured that vibe with sound and song in a way that nobody has or will again.”

In 2010 I asked Kessel about the Gold Star world he witnessed in the sixties and later in the seventies when he recorded there.

“Because the total acoustics of the room for a ‘Wall of Sound’ experience were just perfect. And the way that Dave Gold and Stan Ross designed the studio, they knew what they were doing. It’s not like they said, ‘Let’s roll a wall up here.’ They really had their acoustics down very early in the game.

“Of course the echo chambers and their board that was a heavy metal board, and I don’t mean like in heavy metal music. It was because of the quality of the metal inside the console board and the wiring. It was very thick and very powerful.

“Not like today where you have all the digital stuff and then you have to bring in all the boxes and try to beef it up. You know what I mean? Where at Gold Star that was the real deal.

“The metals made after World War II were sufficiently degraded from the metals before World War II, much weaker metal because they had to use so much during the war.

“It became thinner, got into aluminum, transistors. Stuff like that,” theorized Kessel. “When they have the real deal metal, the real deal magnets, and the real deal wiring, that really enhances the sound.

“And when you bring in brilliant acoustics with a powerful board and then you have Phil and his genius working the musicians and hearing those sounds in his head and being able to articulate it with the help of Larry Levine, Stan Ross and Dave Gold who were outstanding. Gold Star was a special unique studio and so were the guys who ran it.”

In 2002 I interviewed three members of The Ramones for the liner notes to a deluxe compact disc edition of End of the Century.

“I still listen to End of the Century and try to understand what Phil did, which can baffle a lot of people. He’s like a conductor,” summed up drummer Marky Ramone.

“Gold Star had a great room. I was facing Phil and engineer Larry Levine while doing the LP. Phil and I would put a towel on the snare drum on certain songs, an old trick, especially on ‘I Can’t Make It On Time.’ I could see Phil grooving along with my tempo and I knew when he did that he liked it!

“I was amazed how a certain sax can jump in, then a certain guitar tone would pop up . . . the way the roto-toms bounced off the walls to create that low-end hum after the end of the hit, which bounced right back onto the recording.”

“On ballads like ‘Danny Says’,” remarked guitarist Johnny Ramone, “the production work is tremendous. On ‘Do You Remember Rock ’N’ Roll Radio?’ the production works. On some of the things it works, some of the things it doesn’t work. Because of the echo and reverb, I can’t separate; I like to distinguish the guitar from the bass guitar from the drums. I can’t distinguish the separation, because it’s muddy. That’s the sound.

“I wanted to do a Phil Spector song, and then I realized that ‘Baby, I Love You’ was a mistake, and to me it was the worst thing we’ve ever done in our career.

“Looking back, I’m glad I worked with Phil – I worked with a legend of rock & roll. I’m proud to be part of his discography; as far as that goes, I’m glad I did it. At the time I did it, it was very difficult, it was very stressful. There are things I’m happy about, a lot I’m not happy about, but I’m still happy I did it.”

Bassist Dee Dee Ramone was equally intrigued by the album, especially in hindsight: “Now I realize more and more,” mused Ramone, “with time Joey’s voice had a real deep, deep part of the Ramones’ sound. And really that started with End Of The Century.

“I think Phil Spector and Joey were a great combination. Phil brought out the romanticism in Joey. He was like a romantic guy, and some of the songs and productions on End Of The Century pushed that. And ‘Baby, I Love You’ on End Of The Century—I never thought there would be a string section on a Ramones’ record, but I like it.

“The multiple takes really pissed me off. I hate doing that. The Ramones I think, were paranoid not about the sound quality as much as the energy.

“The supplemental musicians on End Of The Century…The guests had to save it. They made an impression on the way things were recorded, and we’re lucky we had ’em. I think I played my bass parts, and Mark played most of the drums, but everybody tried to help make the record. Thank God [engineer/producer/guitarist] Ed Stasium was there, drummer Jim Keltner, and the tall guys, [guitarists] Dan and David Kessel.”

Barry Goldberg, songwriter-producer (as well as the keyboardist with The Electric Flag and Bob Dylan) had one of the most rewarding times of his musical life playing organ, keyboards, and what he calls “a celesta kind of Buddy Holly thing” on the album.

“Phil called me up in 1979, and said, ‘I’ve got something really important for some sessions.’ But he didn’t tell me what it was. I didn’t know until I walked into Gold Star…I went out of my fuckin’ mind walking into that place. It was like Yankee Stadium-in a good way. That room…

“I saw all the Ramones and I loved the Ramones. They were rock ’n’ roll. And I started talking to them, and they found out I played keyboard on the Mitch Ryder stuff, and they loved ‘Devil with a Blue Dress On.’ They accepted me. ‘Danny Says’ is my favorite cut, one of my favorite moments in rock ‘n’ roll.”

Jim Keltner played on “Baby, I Love You.” Jim had known Spector for years and worked with him many times, including dates for Leonard Cohen, and John Lennon in the UK and in Hollywood.

“The Ramones played great together. Their drummer Marky was remarkable,” beamed Keltner. “They had lots of power and energy. It made sense that Phil would produce a record for them. I mean, he’s always been punk.”

Stan Ridgway, musician/songwriter/vocalist, formerly with Wall of Voodoo, who has carved out a stellar solo career since 1983, cited the Spector/Gold Star “Wall of Sound” collaboration as the reason he named his earlier band Wall of Voodoo.

“I tried to go to Gold Star recording studio in the early ’70s, when I first moved to Hollywood from Pasadena,” volunteered Ridgway in a 1999 interview we conducted.

“My goal was to be a janitor and empty trash at Gold Star. OK, I walk in. This is like in 1973, maybe 1972. Nobody was there except the engineer and co-owner, Stan Ross. And he was sitting there in the engineering booth. ‘Look, Mr. Ross, my name is Stan and I’d like to work here. I love the stuff that has come out of this room.’

“Obviously, everything had already happened. There had been tumultuous activity, but that was long ago. So I sat with Stan, and he said there was no work available.

“Then I said, ‘Is that the board that did all the stuff?’ ‘Yeah.’ And he was very nice to me and gave me a tour for a half hour. I got to touch the faders and see what was done. Then I went into the small room.

“That’s where Wall of Voodoo came from. I tore Phil’s records apart, and I tore Brian Wilson’s records apart. Wall of Voodoo started way back when I was trying to form a soundtrack company on Hollywood Boulevard across from The Masque club before it happened. And I used to call it Acme Soundtracks.

“When the rhythm machines came in, I used to collect them and make recordings where I would ‘wall-of-sound’ these rhythm machines at the same tempo to build this sound. I said ‘this is like a Wall of Sound.’

“Then someone came in and said, ‘No, it’s a tropical voodoo thing.’ And I said ‘it’s like a Wall of Voodoo.’ We laughed and joked. We never thought that would be a name for a band.

“And later, when I further investigated Phil’s records, I discovered who the ‘Wall of Sound’ players were. It coincided and dovetailed with my examination and involvement in jazz. ‘Hey man, that’s Barney Kessel playing guitar in there.’ And the West Coast jazz cats doing stuff with Phil – and they had jazz records – were gigging and recording with Shelly Manne. So everything made a lot of sense.

“Phil Spector produced Dion at Gold Star and I loved Dion, another guy and voice who I really communicated with and his whole swagger.

“I really admire Jack Nitzsche. I met with him at Ben Frank’s in Hollywood. It was great. And he told me I didn’t really need a producer. He wasn’t trying to get a gig out of me. Jack was very honest with me. I was a little nervous meeting with him. Jack heard my four-track demos, and said, ‘Get an engineer and do it yourself.’”

(Harvey Kubernik is an author of 16 books. Kubernik’s The Doors Summer’s Gone was published by Other World Cottage Industries in February 2018 and just nominated for the 2019 Association for Recorded Sound Collections Awards for Excellence in Historical Recorded Sound Research.

His literary and music anthology Inside Cave Hollywood: The Harvey Kubernik Music InnerViews and InterViews Collection Vol. 1, was published in December 2017, by Cave Hollywood.

During December 2018, Sterling/Barnes and Noble published Kubernik’s The Story of The Band From Big Pink to the Last Waltz. This century Harvey penned the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, and the Ramones’ End of the Century

From 1975-1980 Kubernik was an occasional food runner and provided percussion instruments and handclapped on a handful of Phil Spector-produced recording sessions at Gold Star. His album credits include The Ramones’ End Of The Century and The Paley Brothers’ Baby, Let’s Stick Together. Harvey also participated on Leonard Cohen’s Death of a Ladies’ Man.

In 1982 Kubernik produced a recording session at Gold Star under his own name).